Playing Past is delighted to be publishing on Open Access – Sport and Leisure on the Eve of World War One, [ISBN 978-1-910029-15-2] – This eclectic collection of papers has its origins in a symposium hosted by Manchester Metropolitan University’s Sport and Leisure History research team on the Crewe campus between 27 and 28 June 2014. Contributors came from many different backgrounds and included European as well as UK academics with the topics addressed covering leisure as well as sport.

Please cite this article as:

Hope, Doug. ‘International Friendships’ with the Co-operative Holidays Association in the Years Leading up to the First World War, In Day, D. (ed), Sport and Leisure on the Eve of World War One (Manchester: MMU Sport and Leisure History, 2016), 116-137.

6

______________________________________________________________

‘International Friendships’ with the Co-operative Holidays Association in the Years Leading up to the First World War.

Doug Hope

______________________________________________________________

Abstract

The Co-operative Holidays Association (CHA), founded in 1893 by Thomas Arthur Leonard a Congregationalist minister from Colne, Lancashire, pioneered ‘rational’ holidays, a concept that developed in the late nineteenth-century as a reaction against the trivialization and commercial exploitation of increased leisure time. The CHA was established to provide ‘simple and strenuous recreative and educational holidays’, which offered ‘reasonably priced accommodation’ and promote ‘friendship and fellowship amid the beauty of the natural world’. Although foreign travel was not one of the CHA’s original objectives, once having experimented with a trip to St. Luc in the Valasian Alps in 1902, the CHA extended its operations across the channel in furtherance of Leonard’s ideals of peace and international brotherhood, with centres in Switzerland, France and Germany. Holidays to Kelkheim in the Taunus in Germany in 1909 brought the CHA into contact with the Musterschule at Frankfurt and led to the formation of the ‘Deutsch-Englischen Feriengemeinschaft’ with similar objectives to the CHA. The CHA’s expansion abroad expressed the internationalism that was a common theme amongst promoters of rational recreation at this time. Based on broader research, this paper concentrates on how the CHA pursued recreative and educational holidays abroad in an attempt to foster ‘International Friendships’ in the years leading up to the First World War. In so doing, it examines accounts of foreign holidays, reported in the CHA’s magazine Comradeship, and assesses the success of British-German exchange visits in promoting peace and goodwill in the years leading up to the First World War.

Keywords: Co-operative Holidays Association (CHA); Rational Recreation; Recreational Tourism; Democratization of Leisure; British-German Relations.

Introduction

The Co-operative Holidays Association (CHA), founded in 1893 by Thomas Arthur Leonard a Congregationalist minister in Colne, Lancashire, pioneered ‘rational’ holidays, a concept that developed in the late nineteenth-century as a reaction against the trivialization and commercial exploitation of increased leisure time. The CHA was established to provide ‘simple and strenuous recreative and educational holidays’, which offered ‘reasonably priced accommodation’ and promote ‘friendship and fellowship amid the beauty of the natural world’.[1] In Colne, Leonard saw an opportunity to fulfil his desire to enrich the lives of young folk ‘who did not know how to get the best out of their holidays’.[2]

In Colne, when the annual ‘Wakes’ week’ arrived, the overwhelming majority of workers caught the train for Blackpool and Morecambe and spent their hard-earned savings on frivolous entertainments, staying in overcrowded boarding houses. The rambling club he formed was part of his church’s Social Guild. Its purpose was not simply to organize walks but to open up the countryside for both physical and spiritual renewal. The first holidays were to the English Lake District, advertised as ‘Holidays amongst the Mountains: Better than Blackpool, Douglas or Skegness!’.[3]

The emphasis of these holidays was on physical and spiritual fulfilment through communal walking and social activities, religious observance with daily morning prayers, the saying of Grace before meals, and the prohibition of alcohol. The daily rambles were supplemented by ‘field talks on place names, rocks and plants and historical associations’ and evening lectures by leading academics and distinguished professionals such as Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley, minister at Crosthwaite, near Keswick and founder of the National Trust in 1895.[4] It was common practice to sing songs on walks and, by 1901, the CHA had its own songbook, Songs of Faith, Nature and Comradeship, containing a combination of hymns and traditional songs.

In founding the CHA, Leonard was much influenced by contemporary social, philosophical and political thought. He gained inspiration from William Morris, Edward Carpenter and Charles Kingsley. He has been described as a Christian Socialist and disciple of Matthew Arnold and John Ruskin, both of whom he quoted in his sermons.[5] His approach to holiday making is therefore associated with the Victorian concepts of respectability, collectivism and co-operation.[6] Leonard was also an enthusiastic member of the fledgling Independent Labour Party (ILP) in the 1890s and knew many of its leading figures. He shared a platform with Keir Hardy at a meeting in Colne in 1894 and advertised holidays in Labour Prophet, a socialist journal established by John Trevor, a Unitarian Minister who founded the Labour Church.[7] Nevertheless, he was by no means uncritical of the ILP and Labour politics. His main objective, which stemmed from a deep religious conviction, was to further his ideas for the social improvement of working people, particularly young workers.

Figure 1

Dockray Square Congregational Church, Colne, Social Guild in the Lake District, June 1891

Source: Nancy Green Collection

The promotion of friendship and fellowship through social intercourse was a fundamental constituent of CHA holidays. It reflected the motto of the CHA: ‘Joy in widest commonalty spread’ taken from the poetry of Wordsworth.[8] Essential to achieving these goals were the appointment of the host and hostess, volunteers who possessed the ability to inspire guests to enter into the spirit of fellowship. They organized the weekly social programme of talks, games and dancing. Guests were also encouraged to take part in sketches or play the ever-present piano. Although the first holidays were for mill-workers, as the CHA widened its scheme beyond the confines of north-east Lancashire, its clientele broadened out to include workers from a wide range of manual, clerical and professional occupations. Its growth coincided with the increasing number of white-collar workers and the changing status of women; increasing numbers were employed in teaching and clerical jobs in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries.[9] In stark contrast to the established rambling and climbing clubs, the CHA attracted women in large numbers; at some centres women outnumbered men by a ratio of two to one.[10] Few records of early CHA holiday groups have survived but, as recorded in Leonard’s scrapbook, one party included teachers, shop assistants, warehousemen and weavers. Another comprised a cotton mill holiday club, clerks, a carpenter, a dressmaker and two university lecturers.[11] Clearly, almost from its inception, the CHA was not homogeneous in its social composition.

Using rented properties at the beginning, the CHA soon acquired its own centres, called ‘Guest Houses’, according to Leonard, a term borrowed from William Morris’s story of his holidays by the Thames in News from Nowhere; a term similar to the German ‘Gasthaus’, a family owned small hotel, popular amongst English visitors in the late-nineteenth century. By 1913, the CHA had thirteen guest houses spread across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, accommodating some 13,670 guests, carving out a niche in the burgeoning leisure industry.

Although foreign travel was not one of the CHA’s original objectives, once having experimented with a trip to St. Luc in the Valasian Alps in 1902, the CHA extended its operations across the channel, with centres in Switzerland, France and Germany. The CHA’s expansion abroad expressed the internationalism that was a common theme amongst promoters of ‘rational’ recreation at this time. J.A.R. Pimlott evokes this new breed of serious tourists, who:

Like the Grand Tourists before them, saw it [foreign travel] as a means of self-improvement, of which they were eager to take advantage; and soon middle-aged ladies who in the winter evenings sat at the feet of the Christian Socialist lecturers might be found exploring the Louvre at the heels of a guide, and serious-minded young clerks from the Working Men’s College might be seen in their summer vacations at the end of a rope on a Swiss glacier.[12]

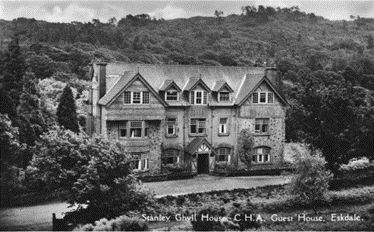

Figure 2

Stanley Ghyll House, Eskdale, opened in 1912

Source: Countrywide Holidays Association

The CHA’s holidays abroad were different from those provided by other organizations such as the Toynbee Travellers’ Club and the Polytechnic Touring Association, which were connected with educational institutions and had a more formal academic interest in foreign countries. They laid more stress on appreciating landscapes and townscapes than interacting with the foreign inhabitants.[13] CHA groups were not just voyeurs, they engaged with local people, their culture and their customs. The CHA’s approach was also based on the desire to bring foreign peoples in closer contact with British life in the interests of the ‘brotherhood of man’. Holidays to Kelkheim in the Taunus in Germany in 1909 brought the CHA into contact with the Musterschule at Frankfurt and led to the formation of the ‘Deutsch-Englischen Feriengemeinschaft’ with similar objectives to the CHA. About the same time, John Lewis Paton, High Master of Manchester Grammar School and close friend of T. A. Leonard, organized school trips to Germany. Exchange visits between Britain and Germany, involving German students and young workers, followed right up to the outbreak of the First World War with CHA members acting as hosts.

This paper concentrates on the CHA’s activities in Europe; how the CHA pursued recreative and educational holidays abroad in an attempt to foster ‘International Friendships’ in the years leading up to the First World War. In so doing, it examines accounts of foreign holidays, reported in the CHA’s magazine Comradeship, and assesses the success of British-German exchange visits in promoting peace and goodwill in the years leading up to the First World War.

First ventures abroad

The first record of the CHA taking parties abroad is to be found in the list of eight centres for 1902. The one centre in a foreign country was at St. Luc in Switzerland where some 432 guests were accommodated through the summer months.[14] According to Leonard in his memoirs, ‘the delectable centre called St. Luc, over 5,000 feet up amongst the Valasian Alps gave us our first taste of the glories of glaciers, alpine flowers, and all the fascinations of the greater heights. In those days we lived luxuriously on 5 francs a day and £8 covered a fortnight’s expenditure including the fare from England’.[15] St. Luc remained a destination for CHA holidays until 1907.

Two new foreign centres were opened in 1907; at Dinan in Brittany and at Dockweiler in the Eifel in Germany.[16] The centre in Dinan was a free standing house in the old walled town called the Villa St. Charles. This accommodated between 700 and 800 guests each year until the outbreak of the First World War. The desire to explore more of the customs and folklore of Brittany led to another centre being opened in 1908 at Le Conquet on the Finisterre peninsular. Holidays to Le Conquet involved over 20 hours of travelling, a somewhat arduous trip; requiring an overnight train from London to Plymouth and a 10 hours steamer crossing from Plymouth to Brest. In an article in the CHA’s magazine Comradeship entitled ‘Easter at Le Conquet’, one guest expresses the unbridled joy they felt on arrival there:

A dream of golden furze, blue seas, flashing lights from distant lighthouses, white, white sands! And over all a bright spring sunshine that made us forget that there could be grey days anywhere![17]

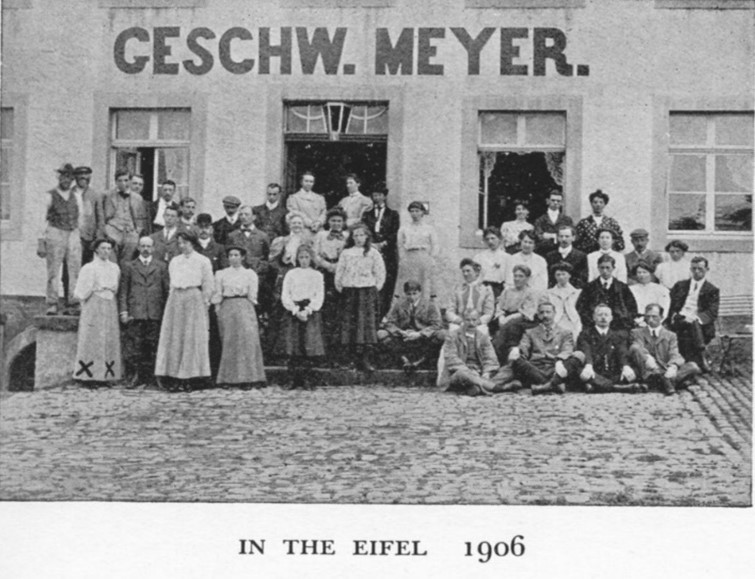

Figure 3

Gasthaus Geschwister Meyer, Dockweiler, Eifel

Source: Countrywide Holidays Association[18]

The steamer leaves Le Conquet pier according to the tide for Camaret, where the interesting Grottoes are visited. Lunch at the Semaphore. Walk to the Point des Pois, returning to the quay by way of the Ecole Communale. Visit the Sailors’ Institute and Sardine Factories.

Other excursions included visits to the Chateau de Kergroadez, a prime example of Breton Renaissance architecture, the Abbaye de St.Mathieu and to the island of Ouessant (Ushant), the most westerly point of France and a site of dramatic granite cliffs and surging seas. However, as the Comradeship article also stresses: ‘But after all the great interest of our corner of Finisterre does not lie in the rocks and the scenery, nor in its fascinating architecture, or plant life, but rather does it centre round the peasant himself’.[20] Recognizing the value of communication with the local inhabitants, the CHA organized French and German classes at its headquarters in Manchester and advertised for hosts and hostesses, who accompanied guests on the trips, who could speak fluent French and German.[21]

Singing together also cemented relationships between the visitors and the local population and the CHA song book included French and German songs, including La Marseillaise, Der Gute Kamerad and Der Tannenbaum. At the German centre in the Eifel, an old-fashioned Gasthaus Geschwister Meyer, there was a weekly ‘Anglo-German singsong’ outside the house.[22] In his memoirs, Leonard recounts how this custom had interesting consequences after the First World War. British soldiers in the army of occupation, when passing through Dockweiler, heard the strains of ‘John Peel’ through the open doors of the local school, which prompted the enquiry as to how these German youngsters had learnt to sing this most English of songs. The response was that English visitors (the CHA) had visited the village before the war and left a song book behind. ‘John Peel’ had become one of the local volksleider (folk songs).[23] A detailed account of a week’s holiday at Dockweiler in the May 1908 issue of Comradeship extols the homely atmosphere of the living quarters and, when the guest house was unable to accommodate all the visitors, guests were put up by the villagers; ‘Perhaps the best thing that could have been done; it makes us more perfectly acquainted with German home-life than otherwise we should have been’.[24]

Figure 4

Above Finaut, looking towards the Bernese Oberland

Source: Countrywide Holidays Association

In 1908, the Swiss centre at St. Luc was replaced by the Hotel Mont Blanc at Finhaut, situated in the western Alps above the Rhone Valley, a decision no doubt influenced by the writings of John Ruskin, who travelled extensively through this part of Switzerland in the 1840s and 1850s, and considered this natural paradise an extension of the Romantic, distinctly northern culture of the English Lake District; the natural and social embodiment of the undisturbed organicism of the ‘old times’.[25] Here, guests experienced views of the grandeur of the Bernese Oberland in one direction and the ice clad peaks and astonishing, sharp aiguilles of the Mont Blanc massif in the other. Excursions included ascents of the Illhorn (2,700m high) and the Weisshorn (4,500m high) near Zermatt and expeditions to the Mer de Glace above Chamonix on the northern slopes of Mont Blanc.

An article entitled ‘Night on the Alps’ aptly describes an overnight ascent of the Sijeur above Finaut in the dark, ‘stumbling over rocks, the steel points of the alpenstocks ringing out a merry tune in the midnight air’, to experience the dawn breaking over Mont Blanc:

There a sight of superb beauty greeted us. The coming of the sun was heralded by a rosy glow behind the chain of peaks that form the Bernese Oberland, and the hinterland of cloud beyond Mont Blanc was tinted an opal grey. Soon the pale flush of rose changed to a bursting flood of carmine and the steel-grey snows took on an orange hue. A moment later, the splashes of blood-red flame behind the Oberland became more gloriously vivid and a tiny point of golden light sprung into being and shot a gleam of yellow sunlight on to the topmost crest of Mont Blanc, transmuting its steely snow and ice into gold. As the sun rose in full-orbed majesty, the triumphant light touched the summits of lower peaks, one by one, the haze of dawn and the mists of morning fled with the night that bore them, the whole valley filled with warmth and nature turned lyric with joy.[26]

So successful was the centre at Finhaut that another centre at Fionnay, a little further up the Rhone valley and situated close under the Grand Combin, the highest mountain between Mont Blanc and the Matterhorn, was opened in 1913. Together with Finhaut, this centre provided a multitude of strenuous excursions into the maze of mountains between Zermatt and Chamonix. At Finhaut and Fionnay, the middle-class members of the CHA were able to indulge themselves in alpine mountaineering and walking, activities that had previously been the sole preserve of the upper classes. The CHA thus contributed to the significant expansion of the middle classes travelling to the Alps, which had commenced in the 1860s following the development of the European railway system and had increased in the subsequent decades when entrepreneurs such as Thomas Cook offered popular walking tours.[27] To ensure that CHA guests fully enjoyed their alpine experience, ‘Hints for walkers among the Swiss mountains’ gave advice not only on clothing and footwear but also on such matters as the gymnastic exercises to be undertaken before the holiday commenced. It also proffered detailed guidance on ascending and descending glaciers and steep snow slopes, and on ‘How to avoid accidents’, on ‘Keeping cool in emergencies’ and on ‘Obedience to the Guide’.[28]

By allowing women to take part in these holidays, the CHA played its part in counteracting the male domination of the Alps, a topic explored by Clare Roche in her paper ‘Women Climbers 1850-1900: A Challenge to Male Hegemony?’. This highlights the wide variety of levels with which women engaged in mountaineering in the Alps during this period, from first ascents of major summits over 4,000 metres to lower level walks.[29] In order to ensure that women were fully equipped for the exertions involved, a special leaflet was produced by the CHA on ‘Suitable dress for foreign holidays’. This provided detailed instructions on the nature of the clothing and footwear to be worn, including under-clothing, blouses and skirts, and the precautions to be taken against sunburn, bites and stings. For climbing, knickerbockers with no petticoats were deemed essential. Long skirts on climbing expeditions were considered a serious danger, not only to the wearers but also to those of the party below them ‘as they are apt to start falling stones’. Trimmings and braids on petticoats and skirts were frowned upon as being dangerous.[30]

Figure 5

Ascending the Corbassière glacier, above Fionnay

Source: Countrywide Holidays Association

The holidays to Switzerland were a great success and continued right up to the outbreak of the First World War.[31] Indeed, holidays to Switzerland and to Brittany were still taking place in the last week of July 1914 and a party to Switzerland due to leave London on 1 August was only just stopped in time. Those, however, who had travelled to Finhaut the previous week, were stranded in Switzerland, following the outbreak of war on 4 August, owing to the complete breakdown in passenger transport through France. They only reached London on 30 August following the commissioning of a special train by the British Embassy in Berne, which transported over 800 people through France to the Channel ports.[32] How the last party of 80 CHA guests escaped from Dinan on 4 August is eloquently described in an article entitled ‘The Departure from Dinan’ in the October 1914 issue of Comradeship.[33] The organization of the departure, following the order to mobilize troops and the requisitioning of every horse and all motorized transport, is testimony to the good relationships between the CHA and the local population. Special permits were required to undertake any travel and how to get 80 people the seventeen miles from Dinan to the port at St. Malo became a major undertaking. Eventually, a vedette (motor boat) was commissioned from a local man and the local Préfet’s lunch was interrupted to obtain the necessary permit, remarking, while he did so: ‘that he would do anything in his power for his English friends’.[34] An hour later, the whole party were aboard the motor boat and sailing down the river Rance towards St. Malo where they boarded the steamer, Princess Ena, the last boat to leave St. Malo for England.

Our friends, the Germans

There was a pacifist under-current to Leonard’s approach to internationalism. At Colne, in one of his many addresses in the years leading up to the First World War, he spoke of his grave fears of war between Britain and Germany.[35] In an article in Comradeship in 1908, John Lewis Paton, the son of John Brown Paton, founder of the CHA with Leonard, reflected the views of many in the CHA when he said: ‘Instead of fighting the Germans, there are no people from whom Englishmen can learn more. Not that it is all one-sided. I believe we have much to teach them in return’.[36] It is no surprise, therefore, that the CHA concentrated its efforts on developing its German centres and, in 1909, the Hotel Taunusblick at Kelkheim in the Taunus Region of Germany, situated between the rivers Main, Rhine and Lahn, replaced the smaller Gasthaus Geschwister Meyer at Dockweiler in the Eifel. An article in Comradeship, announcing the opening of this new CHA centre, describes the chief interest of the area as: ‘its forested hills, spa towns, quaint villages and medieval castles, whilst the nearness of Frankfurt and Wiesbaden makes the district an excellent one for English people who wish to get in touch with some of the most distinctive features of German life’.[37]

On the first trip to Kelkheim, Leonard and his party were entertained by the Burgermeister, Franz Cramer, and his wife. The hotel possessed ‘simple homely German appointments’ and was situated in ‘the midst of deep cool pine woods, into which we retreated on hot off days with our deck chairs’.[38] The Taunus offered miles of high-level mountain walking on way-marked routes, a novelty to the British guests who were more used to being denied access to mountains and moorland. Days were spent tramping the hills in the company of the local rambling club, visiting archaeological sites, including the reconstructed Roman camp at Saalburg, historic towns such as Cronberg and Weisbaden, or sailing on the ‘the most picturesque portion of the Rhine’, with visits to, Bingen, Boppard and Coblenz.[39] Leonard was impressed by the number of local people out walking, including: ‘bonnie children, with light cotton clothing, carrying tiny rucksacks and specimen boxes out under the guidance of their teachers for a two or three days’ holiday in the Taunus’, a practice that was known as a ‘school journey’ and led to the establishment of the Jugendherbergen (youth hostel) organization by Richard Schirmann, a Westphalian school-teacher, in 1910. Leonard became a firm advocate for the establishment of a similar organization in Britain and was instrumental in the foundation of the Youth Hostels Association (England and Wales) in 1931.[40]

Evenings were devoted to lectures on German social and cultural history and to the traditional musical evening, where guests and locals sang together. Articles and photographs in the CHA archive illustrate the extent to which British visitors socialized with local inhabitants.[41] Leonard, along with many educationalists, considered that the study of languages was crucial to international understanding and many guests spoke German, having taken advantage of the classes provided by the CHA, whose headquarters were in the heart of the University District of Manchester, and could call on the services of language teachers from that institution. A particular feature of German life, the traditional beer garden, which Leonard feared might prove a drawback, for the CHA was a temperance organization, turned out to be an attraction to most of the guests. The beer garden was a social event, where German parents were happy to take the whole family, including young children and even babies, with them. According to Leonard: ‘On Sundays, these afforded us an opportunity of seeing how German working folk spent their leisure, as well as of noticing some of the characteristics of the family life of the country. What struck us most was the absolute orderliness of everything and the absence of drunkenness’.[42] A stark contrast to Leonard’s experiences in Colne!

Figure 6

Sailing on the Rhine in 1911

Source: Countrywide Holidays Association

A visit to Frankfurt provided the opportunity to learn more about the institutions responsible for the government of the area and to deepen interest in the social and cultural aspects of German life. Here the party were welcomed by Max Walter, Direktor of the Musterschule (Model School), and August Lorey, a prominent linguist who had taught German at the Manchester Grammar School, where J.L. Paton was High Master. They visited the Opera House, Goethe’s birthplace, the Cathedral and the Städel Art Gallery in the company of Dr Julius Hülsen, the City Architect, also a historian, archaeologist and painter of note. At the Rathhaus (Council House) they were greeted by the Ober Bürgermeister Franz Adickes, one of the founders of Frankfurt University and whose achievements in transforming Frankfurt in the nineteenth century had given him a world-wide reputation. At the new Festhalle, opened in May 1909 and then the largest auditorium in Europe, the CHA guests gave the welcoming party an impromptu rendition of a selection of CHA songs. The visit was concluded by the taking of tea in the Palmgarten, where the visitors were welcomed by Baron von Siebold, President of the Anglo-German Friendship Association.[43]

The high profile welcome in Frankfurt and the calibre of the dignitaries who entertained the CHA party is testimony to the high regard in which Leonard and the CHA were held and to the importance attached to Anglo-German relations by elements of German society at this delicate period of the twentieth century. The success of this first visit to Kelkheim and the contact with the Frankfurt Musterschule led to the establishment of the ‘Ferienheimgesellschaft’ (Association of Holiday Homes) with similar objectives to the CHA. The purpose of this organization was not only to facilitate the expansion of the number of centres in Germany based on CHA principles but also to promote the opportunities for travel to CHA centres in the United Kingdom.[44] The first ‘Ferienheimgesellschaft’ group, comprising teachers and other young people, visited Britain in July 1910, staying in CHA guest houses and University halls of residence.[45] The group, in three separate parties, toured Britain from Beachy Head to Ben Lomond visiting Oxford, Stratford-upon-Avon, the Peak District, North Wales and Scotland as well as spending time in London. The three weeks’ long trip combined strenuous walking in the Derbyshire Peak District, North Wales and Scotland with educational and cultural visits, including a visit to Port Sunlight model village, a precursor of the English garden city movement, which was much admired in Germany.[46]

The parties were accompanied by CHA members who acted as hosts and by distinguished guides, reciprocating the welcome given in Frankfurt. Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley, founder of the National Trust accompanied the guests. In London, the party was guided by T.P. Figgis, a distinguished architect, whose best known works are the original station buildings for the City & South London Railway (now part of the Northern Line), which opened in 1890. In Oxford, their host was Hermann Fiedler, Professor of German. In Stratford, they were welcomed by Frank Benson, Director of the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre. In Derbyshire, they stayed at the CHA’s guest house, Park Hall, at Hayfield where they spent days hill-walking on the surrounding moors (many years before the Kinderscout Trespass) and visiting stately homes. In North Wales, based at the University College of Wales, Bangor, ascents were made of Snowdon and visits made to Aber Falls, the Ogwen Valley, Anglesey and the Stacks Lighthouses. In Scotland, the parties stayed at the CHA’s guest house, Ardenconnel, near Gairloch on the Clyde, where visits were made to the Isle of Arran and Loch Lomond, and an ascent made of Ben Lomond.

Figure 7

The ‘Ferienheimgesellschaft’ at Park Hall, Hayfield

Source: Countrywide Holidays Association

In London, the German guests were entertained by the London CHA Rambling Club, which had its own guest house, Ashburton House, at Addiscombe.[47] Whilst staying in London, the German guests visited the House of Commons and were entertained to tea by Ramsay MacDonald MP, a friend of Leonard since his days with the ILP. After the visit, Ramsay MacDonald, who was opposed to the First World War, wrote to the CHA:

Will you please assure your German friends that if they were delighted by being at the House of Commons, I was equally delighted to have them! I hope that the visit is giving them assurances that cannot be questioned, that the mass of English people desire nothing but the most friendly co-operation, and that the sections which seek to stir up strife between us, if rich and influential because they own the Press, are nevertheless small in numbers, and can be easily overcome by a friendly and intelligent democracy on both sides of the North Sea.[48]

The establishment of the ‘Ferienheimgesellschaft’ in Frankfurt was quickly followed by a similar organization in Berlin; the ‘Vereinigung der CHA Freunde’ (The Association of Friends of the CHA). As explained in a letter from the organizing committee, published in Comradeship:

The origin of this idea is the remembering of the pleasant time we Berlin people spent in the centres of the CHA, enjoying the hospitality, kindness and friendship of CHA members in England. Wanting to keep up these recollections and to get informed about the opinion of the other Berlin CHA visitors, we had a gathering on November 6th. Everybody took great interest in our idea and so the foundation was agreed to.[49]

The aims of the Berlin Association of Friends of the CHA was to spread the philosophy of the CHA through the organization of lectures and social gatherings ‘with songs, recitations, exchange of recollections and chattering’, and to encourage members to visit the CHA in Britain. As a consequence, CHA exchange visits commenced between the CHA and the Berlin ‘Vereinigung’, with CHA members spending time tramping amongst the forests of the Harz Mountains before exploring Berlin. A meeting at Berlin University in 1913 led to the formation of the ‘Kameradschaft der CHA’, a comradeship consisting of students, who, having visited England under the auspices of the CHA pledged themselves to promote good relations between Britain and Germany, through the arrangement of visits to each other’s countries.[50]

Educational exchanges between Britain and various European countries was an important component of the CHA’s pursuit of the ‘Brotherhood of Man’. From 1908, J.L. Paton, High Master at Manchester Grammar School, had been sending parties of schoolboys trekking across Germany. Following the CHA’s first visit to Kelkheim and Frankfurt in 1909, Leonard took up the challenge and schoolboys from the Musterschule visited Britain. After spending a week with CHA members, they went for a month to different CHA guest houses in the Peak District, the Lake District and Scotland, finishing at the CHA’s London centre.

These groups were assisted by schoolteachers and academics, professionals, and politicians. They were well supported by CHA members, as references in Comradeship testify, and also enjoyed by the recipients. The following two contributions, dating from November 1911, are typical, and illustrate the optimism, to be proved somewhat misplaced, about future relations between Britain and Germany.[51] The first extract is from a letter by a CHA member, the second from a young German student, written on his return home. E.D.T. (a CHA member writes):

We were amply rewarded for our momentary misgiving at the thought of having to entertain a strange boy, by the immense pleasure we have afterwards experienced in having him with us. The trouble will be at the parting on Saturday, as we have got to like him very much indeed. There can be not the slightest doubt of the benefit accruing to both nations from this ideal intercourse between the young offshoots of both countries. The friendship which I am sure has been cemented between our charming guest, Ludwig, and our own boy cannot fail to be continued through life with results for good that none can tell, and through them between the respective parents.

C.P., a young German guest, returning home after four weeks in Britain at CHA guest houses, wrote to the CHA:

These days have been of the greatest importance for me, for not only have I seen some of the loveliest spots of dear old England, not only have I thus been able to study English life and customs so well, but – and I consider this as the highest benefit – I have learnt to like and esteem the English people just as if they were my own countrymen.

These exchanges became firmly established and continued right up to the outbreak of the First World War. British boys spent three weeks on tramp with the Wandervögel and one week in Frankfurt, staying at the homes of German friends of the CHA.[52] Thus, whilst German schoolboys tramped with their British hosts in the Yorkshire Dales, The Peak District and the Lake District, British schoolboys, mainly from the north of England, walked in the Taunus and the Black Forest, where the CHA established another German centre at Wolfach. At a time when the country was moving, inexorably, towards war with Germany, with the Morocco Crisis of 1911, and the conflicts in the Balkans, the CHA continued undeterred to pursue its aim of ‘International Friendship’ through recreative and educational holidays for ordinary young people. As late as May 1914, the CHA was arranging a visit of German schoolboys to Britain and advertising for volunteers to put them up in early July.[53] Pioneer parties, the term used by the CHA to describe the first holiday groups, to the Austrian Tyrol and to the Belgian Ardennes were also being planned. The destination for the Austrian trip was Sölden situated at a height of 4465ft. in the Ötztal valley, a lateral valley of the Inn, incidentally the winter location for filming the latest James Bond movie in 2014, but in 1914 a quiet, remote location, with ‘wild ravines terminating in a vast expanse of snow and glacier’.[54] The cost of the holiday was £11, which included a 2nd class railway ticket from London to Innsbruck and back via the Folkestone to Boulogne steamer, hotel accommodation for two weeks, local excursions and incidental expenses (a comparable holiday would cost in excess of £1,000 today). Ladies were welcome on this trip but it was made clear that ‘the excursions will be strenuous’. It was advised that ‘only those who have been to the Swiss centres or Eskdale (Stanley Ghyll House in the Lake District), or have had some experience of climbing should apply’. The planned date for departure was 22 August, 1914, but, in the event, the trip was cancelled and the CHA did not manage to reach Austria until 1924.

The trip to the Belgian Ardennes reflected more the CHA’s love of culture and history. Centred on Rochefort, in a district of ruined castles perched high on rocky cliff-sides, romantic legends and folklore, it was comparatively unknown by British visitors. The area provided a wide range of walking opportunities; gentle walks amidst green pastures or stiffer walks alongside rushing streams in narrow ravines. The thickly wooded hills of the Ardennes, still inhabited by wild boar and stag, also provided a myriad of forest walks. In contrast to the Tyrol excursions, the holidays to the Ardennes did not ‘call for great powers of endurance’.[55] However, the main attraction of the Ardennes was its accessibility. Leaving London at nine in the morning, making use of the Dover to Ostend steamer, the party reached Rochefort in the early evening having passed through Bruges, Ghent, Brussels and Namur. Rochefort was only three miles from the nearest railway station. The cost of the holiday was £6, inclusive of 2nd class train ticket, 1st class boat and 13 days hotel accommodation. The cost of excursions was not included but was estimated to be between 10s and 12s 6d for the fortnight. A party of some thirty people undertook the first holiday, leaving on 4 July, 1914, and managed to return home safely having ‘explored the district under the most favourable of weather conditions’.[56] Within a very short time, weather and ground conditions around Rochefort had changed beyond all recognition. As the October issue of Comradeship reports: ‘The countryside, which then looked so happy and peaceful, now lies ravaged and its villages in many cases destroyed. Dinant, which we visited on several occasions, is largely a heap of ruins. We fear it will be some time before we shall be able to consider the possibility of establishing a centre there!’. Dinant suffered devastation at the beginning of the First World War; on 23 August, 1914, 674 inhabitants were summarily executed by the Saxon troops of the German Army, the biggest massacre committed by the Germans in 1914. Within a month, some five thousand Belgian and French civilians were killed by the Germans at numerous similar occasions. Amongst the wounded was one Lieutenant Charles de Gaulle.[57]

Holidays to Europe did not re-commence until 1920 when the Dinan centre in Brittany was re-opened. A visit was made to Fionnay in Switzerland in 1921 but it was 1924 before the CHA returned to Belgium and the long-awaited trip to Austria took place, and it was 1927 before Germany was re-visited when a centre at Boppard on the Rhine, not far from Kelkheim, was opened.[58] Although these holidays abroad were in the pursuit of ‘International Friendship’: ‘for intercourse between ourselves and those Continental peoples with whom we must eventually be friendly if the sharp national divisions of to-day are ever to be bridged’, there are no records of the ‘Ferienheimgesellschaft’ group in Frankfurt being resuscitated or of the ‘Kameradschaft der CHA’, in Berlin, or of any involvement of the CHA in the British – German school exchanges that were so successful prior to the First World War.[59]

End piece

As Robert Snape remarks, in establishing the practice of providing simple, affordable and non-exclusive accommodation; welcoming women on the basis of equality; and promoting greater access to the countryside, the CHA laid the foundations of the spirit of fellowship that came to characterize walking and rambling in the twentieth century.[60] Although foreign travel was not one of the CHA’s original objectives, Leonard’s interest in international relations led the CHA to involve itself in holidays abroad. Foreign travel, aimed at cementing the bonds of international friendship, was a common theme amongst promoters of rational recreation in the years leading up to 1914.[61] This ran counter to the dominant trend of late-Victorian Britain; that of isolationism based on a growing unease at the Boer War, the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire and the nationalist ambitions of Russia and Germany.[62] There was a pacifist undercurrent to Leonard’s approach to Internationalism. The CHA’s approach was based, therefore, not only on leisure and educational trips abroad but also on a desire to bring foreign nationals in closer contact in the interests of the ‘Brotherhood of Man’. In this respect, the CHA’s foreign holidays were different to those of other contemporary organizations, such as the Toynbee Travellers Club and the Polytechnic Touring Association, and commercial organizations such as Thomas Cook. CHA groups did not just travel through the landscape, admiring fine buildings and the view, they engaged with local people, their culture and their customs. As a result, CHA holidays enabled hundreds, if not thousands, of ordinary British working people the opportunity to experience foreign lands and foreign peoples.

Under the strong influence of its founder, the CHA pursued ‘International Friendships’, particularly in Germany, through the formation of like-minded organizations such as the ‘Ferienheimgesellschaft’ group in Frankfurt and the ‘Kameradschaft der CHA’, in Berlin. Student and school exchange visits and shared holidays supported by members of the CHA enabled young people from both sides of the Channel to engage in communal walking and socializing, and to experience each other’s cultures at close quarters. Leonard, like many politicians, academics and social reformers, believed that international friendship, especially between young people, would be the key to international peace. However, that was not to be; the ideal of the ‘Brotherhood of Man’ could not prevent the inexorable march towards conflict. Nevertheless, although the efforts of Leonard and others did not prevent the ‘war to end all wars’, his vision of international harmony survived and the CHA, together with its sister organization the Holiday Fellowship, was at the forefront of the movement to foster international understanding and friendship in the inter-war era by organizing holidays in Europe for young people, who were increasingly turning to the countryside and open air for its restorative powers. These organizations would be joined in 1921 by the Workers’ Travel Association (WTA), founded by Cecil Rogerson who gained his early inspiration from his time spent hosting holidays with the CHA and Holiday Fellowship. The WTA was set up primarily to promote foreign travel aimed at facilitating greater international understanding amongst workers.[63] This organization would be followed, in 1931, by the Youth Hostels Association (England and Wales), with which T.A. Leonard was also associated and both the CHA and Holiday Fellowship strongly supported. Although the YHA would not be established until the 1930s, it could trace its origins to the Jugendherbergen (Federation of German Youth Hostels) founded in 1913, which was popular with British students in the 1920s, and with members of the CHA and Holiday Fellowship.[64] ‘International Friendships’ would continue through the establishment of the International Youth Hostel Federation in 1932, that is until the intervention of Adolf Hitler. But that is another story!

References

[1] Thomas A. Leonard, Adventures in Holiday Making (London: Holiday Fellowship, 1934), 28; see also, Constitution, adopted January 1897, B/CHA/ADM/1/1, Countrywide Holidays Association archive, Archives+, Manchester Central Library.

[2] T.A. Leonard, Adventures in Holiday Making, 19.

[3] Posters and leaflets, B/CHA/HIS/3, Archives+, Manchester Central Library.

[4] Fanny Pringle, ‘A Week among the Lakes’, Independent and Nonconformist, 31 August 1893, 164, B/CHA/HIS/17, Archives+, Manchester Central Library.

[5] Robert Snape, ‘The Co-operative Holidays Association and the Cultural Formation of a Countryside Leisure Practice’, Leisure Studies, 23 no. 2 (2004): 143-158.

[6] F.M.L. Thompson, The Rise of Respectable Society: A Social History of Victorian Britain, 1830-1900 (London: Fontana, 1988); B. Anderson, ‘Partnership or Co-operation? Family, Politics and Strenuousness in the pre-First World War Co-operative Holidays Association’, Sport in History, 33 no. 3 (September 2013): 260-281.

[7] Colne and Nelson Times, October 26, 1894, 5; Labour Prophet, June 1894.

[8] Taken from the poem ‘The Prelude’, see Edwin de Selincourt (ed.) Poetical Works of William Wordsworth (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1969).

[9] E.J. Hobsbawm, The Age of Empire 1875-1914 (London: Weidenfield & Nicolson Ltd., 1987), 41.

[10] Comradeship, V, no. 5 (April 1912), 35, B/CHA/PUB/1/1, Archives+, Manchester Central Library.

[11] Echoes (c.1900), B/CHA/HIS/16/1, Archives +, Manchester Central Library.

[12] J.A.R. Pimlott, The Englishman’s Holiday (London: Faber & Faber, 1947), 191.

[13] E. Penn, (ed.), Educating Mind, Body and Spirit: The Legacy of Quintin Hogg and the Polytechnic, 1864-1992 (Cambridge: Granta, 2013); J.D. Browne, ‘The Toynbee Travellers’ Club’, History of Education, 15 no. 1 (1986): 11-17.

[14] CHA holiday programme for 1902, B/CHA/PUB/5/1, Archives+, Manchester Central Library.

[15] Adventure in Holiday Making, 39.

[16] CHA holiday programme for 1907, B/CHA/PUB/5/1, Archives+, Manchester Central Library

[17] ‘Easter at Le Conquet’, Comradeship, 1 no. 5 (May 1908): 68, B/CHA/PUB/1/1, Archives +, Manchester Central Library.

[18] R. Speake, A Hundred Years of Holidays, 1893-1993, 33.

[19] CHA holiday programme for 1908, B/CHA/PUB/5/1, Archives+, Manchester Central Library.

[20] Ibid.

[21] ‘Wanted’, Comradeship, 1 no. 5 (May 1908), 66, B/CHA/PUB/1/1, Archives+, Manchester Central Library; ‘French and German’, Comradeship, 3 no. 1 (September 1909): 3.

[22] Robert Speake, A Hundred Years of Holidays, 1893-1993 (Manchester: Countrywide Holidays, 1993), 33.

[23] T.A. Leonard, Adventures in Holiday Making, 44.

[24] ‘Holidays in Rural Germany’, Comradeship, 1 no. 3 (February 1908): 40, B/CHA/PUB/1/1, Archives +, Manchester Central Library.

[25] For an account of Ruskin’s travels in Europe, particularly Switzerland, see Keith Hanley and John K. Walton, (eds.), Constructing Cultural Tourism: John Ruskin and the Tourist Gaze (Bristol: Channel View Publications, 2010), 43-54, 92-100.

[26] Comradeship, 5 no. 2 (November 1911), 24-25, B/CHA/PUB/1/1, Archives+, Manchester Central Library.

[27] J. Buzzard, The Beaton Track: European Tourism, Literature and the Ways to Culture, 1800-1918 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993).

[28] Comradeship, 7 no. 5 (May 1914), 73-74, B/CHA/PUB/1/2, Archives+, Manchester Central Library.

[29] Claire Roche, ‘Women Climbers 1850-1900: A Challenge to Male Hegemony?’, Sport in History, 33 no. 3 (September 2013), 236-259.

[30] See leaflet, B/CHA/HIS/2, Archives+, Manchester Central Library.

[31] Comradeship, 7 no. 4 (March 1914), 56-58, B/CHA/PUB/1/2, Archives+, Manchester Central Library.

[32] Comradeship, 8, no. 1 (October 1914), 1, B/CHA/PUB/1/2, Archives+, Manchester Central Library.

[33] Comradeship, 8 no. 1 (October 1914), 7-9.

[34] Ibid., 8.

[35] ‘Former Colne Minister’s Visit to Germany’, Colne and Nelson Times, November 17, 1911.

[36] ‘Our Friends the Germans’, Comradeship, 1 no. 5 (May 1908), 67-68.

[37] ‘In the Taunus’, Comradeship, 2 no. 3 (February 1909), 40.

[38] ‘In the Taunus’, Comradeship, 3 no. 1 (September 1909), 3.

[39] CHA holiday programme for 1909, B/CHA/PUB/5/1, Archives+, Manchester Central Library.

[40] Oliver Coburn, Youth Hostel Story (London: National Council of Social Service, 1950), 3-21.

[41] See for example, ‘Whitsuntide in Germany’, Comradeship, 3 no. 5 (April 1910), 71-73; Photograph albums, B/CHA/PHT/3/1-17; B/CHA/PHT/3/99 & B/CHA/PHT/3/101, Archives+, Manchester Central Library.

[42] ‘In the Taunus’, Comradeship, 3 no. 1 (September 1909), 4.

[43] ‘In the Taunus’, Comradeship, 3 no. 1 (September 1909), 3-5.

[44] ‘Kelkheim’, Comradeship, 3 no. 3 (December 1909), 34.

[45] ‘Germany, France and the CHA’, Comradeship, 3 no. 5 (April 1910), 67.

[46] Programme for visit of Ferienheimgesellschaft, July 1910, B/CHA/HIS/3, Archives+, Manchester Central Library.

[47] S. Brown, The London CHA Club: The First Sixty years (London: London CHA Club, 1965), 1-10.

[48] ‘International Friendships through Holidays’, Comradeship, 4 no. 2 (December 1910), 37-38.

[49] ‘Our Letter Bag’, Comradeship, 5 no. 3 (December 1911), 47.

[50] ‘In Germany’, Comradeship, 6 no. 5 (April 1913), 77-79.

[51] ‘Our Letter Bag’, Comradeship, 5 no. 2 (November 1911), 23.

[52] ’German and English Boys’, Comradeship, 6 no. 5 (April 2013), 66.

[53] ‘Internationalism’, Comradeship, 7 no. 5 (May 1914), 65-66.

[54] ‘Pioneer Holidays’, Comradeship, 7 no. 5 (May 1914), 66.

[55] ‘Pioneer Holidays’, Comradeship, 7 no. 5 (May 1914), 67-68.

[56] ‘General Notes’, Comradeship, 8 no. 1 (October 1914), 1.

[57] J. Horne & A. Kramer, The German Atrocities of 1914: A History of Denial (Newhaven and London: Yale University Press, 2001).

[58] CHA holiday programmes for the 1920s, B/CHA/PUB/5/2 & B/CHA/PUB/5/3, Archives+, Manchester Central Library.

[59] ‘International Friendship’ in CHA 1923 Annual Report, B/CHA/FIN/1, Archives+, Manchester Central Library.

[60] R. Snape, Leisure Studies, 23 no. 2 (2004), 155.

[61] H. Taylor, A Claim on the Countryside (Edinburgh: Keele University Press, 1997), 209-210.

[62] E.J. Hobsbawm, The Age of Empire 1875-1914, 302-327.

[63] Francis. Williams, Journey into Adventure, (London: Odhams Press Limited, 1960) for a history of the Workers’ Travel Association.

[64] Oliver Coburn, Youth Hostel Story (London: National Council of Social Service, 1950), 145-163.