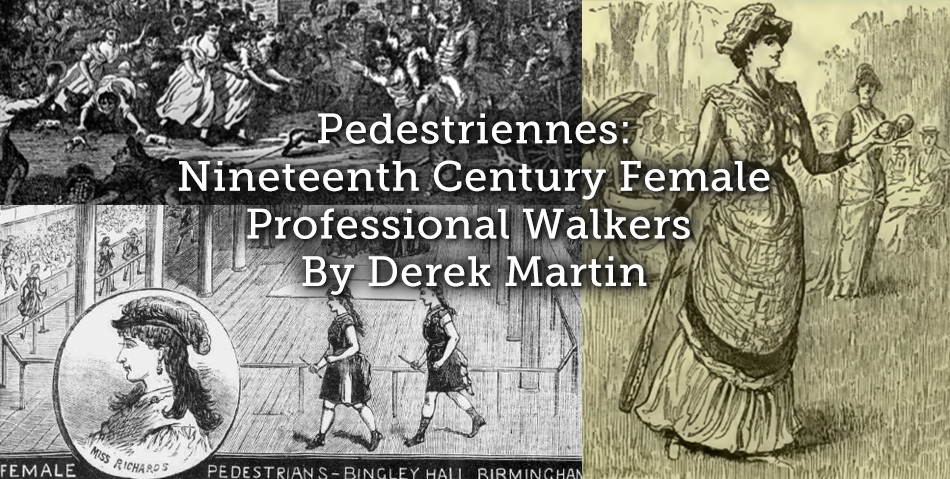

The conventional notion is that in the nineteenth century women simply did not do sports that involved strenuous exercise. In 1891 Punch summed up its view of the progress in female sport over the preceding 30 years, from croquet to golf via a rather sedate form of lawn tennis.

- Punch, 18 July 1891

By this time Punch was already behind the times – the new girls’ schools of the period were already introducing gymnastics, hockey, cricket and other activities that demanded more effort and less clothing. But it wasn’t until after the First War that females were admitted into amateur athletics. It was self-evident that women could run – from the seventeenth to the early nineteenth century there had been women-only foot races, or ‘smock’ races (so-called from the traditional prize for the winner). We have numerous depictions of these races, invariably showing them attracting appreciative (and usually inebriated) audiences.

- Smock Race at Tottenham Court Fair, 1738 (Wellcome Library, London)

The smock race as an institution had died out by about 1820 and with it women’s opportunities to race for gain. For the rest of the century their participation in athletics has been forgotten. But in fact, some working-class women elbowed their way into ‘pedestrianism’. (Pedestrianism was the nineteenth century term for competitive running or walking – from the 1860s the new amateur sport called itself ‘athletics’ and distanced itself from the old professional ‘pedestrianism’).

An iconic part of pedestrianism had been the long endurance walk, made famous by Captain Barclay. He had walked one mile each hour for 1,000 successive hours (42 days) for a wager of 1,000 guineas in 1809. At the beginning of the 1850s male pedestrians revived this ‘Barclay Match’. In two years there were almost twenty events, many of them attracting huge crowds and publicity. Contrary to early Victorian ideology, stamina and endurance were not exclusively male attributes and as interest in the men waned several working-class women broke into this very male world, mainly in the North (Birkenhead, Manchester, Sheffield) and the Midlands (Birmingham, Wolverhampton, Stoke-on-Trent, Trent Bridge) though there were 500-mile matches in Bristol and Plymouth. Half a dozen female pedestrians between 1852 and 1854 walked a dozen Barclay Matches.

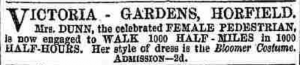

It is safe to say that the women were not participating in any Corinthian spirit. These were strictly money-making affairs, promoted by proprietors of pubs, hotels and pleasure gardens, who already provided music, dancing, fireworks and the all-important ‘refreshments’. The women were an additional attraction; for the admission fee of twopence, they could observe a woman walk, at a set time every hour or half hour day after day, week after week. . The American Mrs Amelia Bloomer, was at the time advocating a new form of emancipated dress for women – the ‘Bloomer Costume’ of ankle-length pantaloons and a loose, knee-length tunic. On the basis that any publicity is good publicity, some of the women’s advertising emphasised the opportunity to see this new, somewhat controversial and widely ridiculed dress style.

- Amelia Bloomer in her famous costume (1851)

- an advertisement for a well-dressed female pedestrian – Jane Dunn’s 500-mile walk at a pleasure garden (Bristol Mercury, 2 September 1854)

The Bloomer fad petered out, as did the vogue for female pedestrians. But in August 1864 London’s biggest music hall, the Alhambra in Leicester Square, advertised a novelty – a pedestrienne would walk 1,000 miles, on a boardwalk 279 feet long that had been built inside the auditorium. The pedestrienne was the 40-year old Margaret Douglas lately arrived from Australia. She was already an experienced pedestrian. She had been among the entertainers who had joined the gold rush in the 1850s and performed in the saloons and music halls that sprang up in the Australian goldfields. She had walked 1,000 miles at Ballarat in 1858.

The Alhambra cancelled her walk abruptly after 34 days and 824 miles. The proprietor without warning dismantled the boardwalk, probably because she was not generating the money he expected. But within two weeks Emma Sharp, a 30-year old working class woman in Bradford began to walk beside the Quarry Gap Hotel in Laister Dyke. She aroused great excitement. The northeners were eager to pay to watch her – there were said to have been more than 10,000 spectators and the press reported that she had made a large amount of money. She finished with music, fireworks in front of huge crowds on 29 October, by which time a new Barclay craze was well under way. Working-class women had already started 1,000-mile walks in Sheffield, Liverpool and Manchester. It was overwhelmingly a phenomenon of the northern industrial towns. Within a month there were Barclay matches in Leeds, Huddersfield, Blackburn, Halifax and Burnley and when the Barclay craze died down there had been upwards of twenty ultradistance walks. There was only one indoor event: Margaret Douglas did a Barclay Match at the Amercian Opera House in Liverpool in Novembether 1864. Apart from that the venues were as they had been in the 1850s, mainly pubs and gardens.

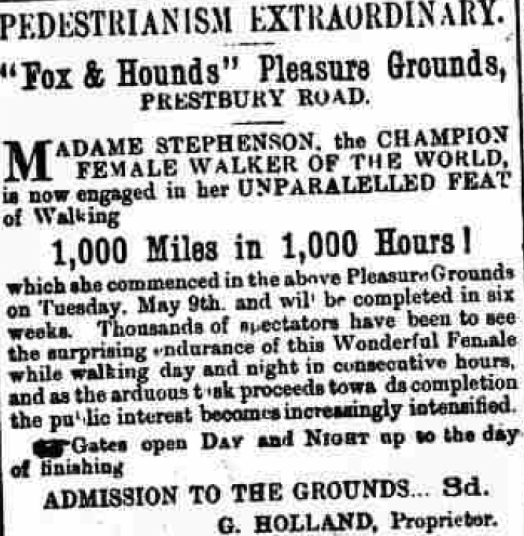

By 1866 this wave of Barclay enthusiasm had ended. But throughout the 1870s a small cohort of increasingly professional pedestriennes developed. Between 1870 and 1884 there were more than 50 ultramarathon walks by more than a dozen identifiable female walkers. For example, a Mrs. Stephenson –

- Cheltenham Mercury, 27 May 1876

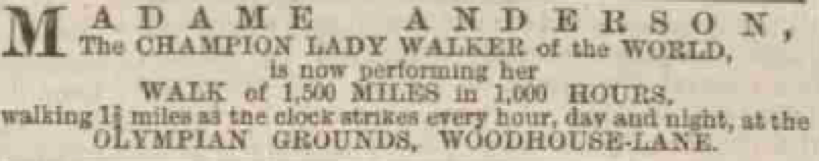

The best of her generation was Ada Anderson, who walked 1,500 miles in 1,000 hours, at Leeds in 1878.

- Leeds Times, 4 May 1878

Ada went to the United States where female pedestrianism was thriving and there was more money to be made. British male pedestrians meanwhile had abandoned the Barclay match format because of declining interes but by 1876 a new form of ultramarathon had revitalised their sport – the indoor, six-day ‘go-as-you-please’ race. Promoters found more or less suitable venues, built tracks of sawdust-covered wooden boards, put up prize money and hoped to make a profit from the entrance money. Competitors walked or ran continuously, day and night, between Monday and Saturday evening; the winners of the big events covered more than 500 miles. The novelty of these events attracted huge interest, crowds and money until the mid-1880s, when they lost their audience.

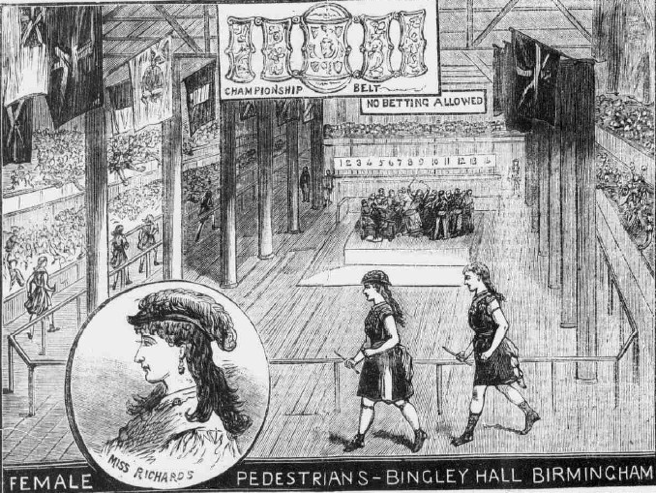

Some promoters put on women-only indoor races. The last of the century’s female pedestrians competed in such events up until 1888. This image shows such a tournament at Birmingham in 1884 where the women walked 10 hours a day for six days for a prize of £40 (the winner managed 209 miles on the 195-yard track).

- Female six-day pedestrian tournament at Birmingham (Illustrated Police News, 29 March 1884)

By then pedestrianism had lost its place in public esteem to amateur athletics, the ethos of which was ideologically opposed to professionalism, to unfeasibly long races in the tradition of Captain Barclay, and which certainly had no place for women. Quickly the story of the pedestriennes was quietly forgotten.

Article © Derek Martin

I enjoyed this article on early pedestriennes. I notice in one of the drawing that the ladies are carry sticks in their hands. What was the purpose of the sticks?