To read the first part of this series click HERE

Who was Violet Piercy?

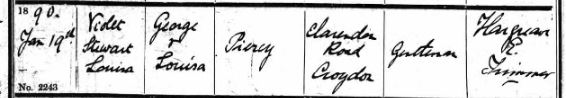

Helpfully Piercy’s name is unusual enough to find in digital searches, even though it was sometimes spelt Piercey. The process of identifying her was aided by newspaper reports of a case in which she was involved in the High Court of Justice in 1932, when she successfully sued her former employer, a Dr Eric Coplans, for slander. The action received extensive press coverage. She was described in The Times as “of some repute in the athletic world”[i] and in the Evening Standard as “a noted woman athlete and marathon runner”.[ii] Her address was given as 21 Leathwaite Road, Clapham Common, SW. A study of census records and electoral rolls established her as living at various south west London addresses around this time. These and other clues confirmed eventually that she was Violet Stewart Louisa Piercy, born at 15 Clarendon Road, Croydon, on 24 December, 1889.

Violet’s 1890 baptism entry in the parish registers of St John’s Church, Croydon

Source: Anglican Parish Registers Surrey History Centre

George Piercy, Violet’s father, is described as “of independent means” on her birth certificate and “gentleman” on her baptism record. He owned land and houses in Croydon and in the 1871 census claimed to have income from fifty rents. He was sixty-eight and in his third marriage when Violet was born. However, he died when she was only two weeks old, on 7 January, 1890.

There are indications that Violet’s mother, Louisa Sophia Piercy, née Beadle, born in 1863, and thirty years younger than George, was an unstable character. They married in 1886 when George was sixty-five, she thirty-five, although she gave her age as twenty-six. A son, Norman, was born in 1888, but died aged eight, in 1897. In 1902, Louisa started complaining about her next-door neighbour in Clarendon Road, claiming that he was forging coins and running an illicit liquor still. She wrote to other neighbours and his employer. In a case reported nationally in the Daily Express, he successfully sued her for libel and she was remanded for a week “that her state of mind might be inquired into”.[iii]

Later the same year, Louisa Piercy was in the newspapers again. There had been reports of a “black ghost” that had haunted Clarendon Road for eighteen months and thrown stones at the windows of John Denyer, the neighbour who had brought the libel case. After a number of breakages, the spectre was identified as Mrs Piercy wearing a black shawl. “I shall do as I like and go where I like on my own premises,” she called back when she was spotted. In the police court she was bound over to keep the peace and provide a surety for her future behaviour.[iv]

Louisa had inherited a portion of the money from George’s estate, including the rents from some twenty houses, and Violet was sent to an independent school in Croydon, Old Palace of John Whitgift. For centuries the building had been the summer palace of the Archbishops of Canterbury, but had become derelict and was converted into a school in the year Violet was born. The ethos of a new school with high aspirations must have been difficult for a child with a delinquent parent. Violet had reached the sensitive age of twelve when her mother’s escapades were reported in the Daily Express. The scandal would not have escaped the school authorities or her fellow students. Violet’s later history suggests that she wasn’t subdued by the experience. She grew into a strong-willed young woman ready to challenge authority and speak up for her principles.

The financial circumstances of mother and daughter declined over the years. In the 1891 census, there was a servant in the house. In 1901, there was a lodger. In 1911, Louisa gave her occupation as “(limited) means”. She gave her own age as 48 (she was 59) and Violet’s as 18 (she was 21). No occupation was given for Violet. They still lived in Clarendon Road, but had moved to number 54, a six-room house. In 1915 they moved again, to a more modest address in Pimlico and in 1916, Louisa Piercy died in the Westminster Poor Law infirmary.

We next hear of Violet in 1919, when she gained probate of her mother’s will and was living in Mitcham. The estate amounted to £364. In 1922 she was in business in Wandsworth, running a valeting service with a male member of the Piercy family. And in 1923 she began her ill-fated employment as secretary to Dr Coplans.

Probate record for Violet’s mother Louisa

Source: National Probate Calendar

Instant Fame

The marathon run made her famous overnight, with newspapers in USA, Australia and New Zealand picking up reports of varying accuracy from London press agencies. The Auckland Star of 5 October, 1926, printed this Press Association item:

In the Windsor to London ladies marathon race Miss Violet Piercey (sic), a member of the British Women’s Olympiad (sic) team, covered the distance in 3 hours 40½ minutes, which is better than the record for the distance by men.

The Auckland Star 5 October, 1926

So a solo run was elevated into a race; the member of London Olympiades AC became a British Olympian; and the time was supposed to be better than the men’s record, which was actually under 2½ hours. When distortions like this appeared across the world within days of the performance it is not surprising that confusion about Violet’s first famous run remained uncorrected for over eighty years.

Of all the press reports, the most detailed we traced was in the Westminster Gazette of 4 October:

Woman Runs 20 Miles: Marathon Course Conquered

The famous Marathon course from Windsor Castle to London has for the first time been conquered by a woman, Miss Violet Piercey (sic), a member of the London Women’s Olympiad (sic), covered the distance of just over twenty miles on Saturday in 3hr 40m 22s. Accompanied by two motor-cars containing a number of friends, Miss Piercey started at 4.20 pm and made good progress to reach Hounslow by 5.40 pm. From there she was greatly hampered by the suburban traffic, and consequently she did not reach her objective, Battersea Town Hall, until 8 o’clock.

Remarkable Feat

She was remarkably fit after her long run and said she was prepared to repeat her achievement. ‘I did it because I wanted to show the Americans what we can do,’ she said, ‘and to prove that Englishwomen are some good after all.’ Major W.B.Marchant, Honorary Secretary of the Women’s Amateur Athletic Association, told the Westminster Gazette that it was a remarkable feat for a woman. ‘It is one of the rules of the Association,’ he said, ‘that no race shall exceed 1000 metres, but as this was a personal effort there is no question of calling Miss Piercey to book.’

The Gazette’s estimate of the distance was probably about right, and the mention of Hounslow confirms that the route taken did not match the original course from 1908, which followed an arc shape through North-West London. Violet Piercy must have taken a more direct line along the Great West Road, cutting several miles from the total distance. The finish at Battersea was another variation. The Olympic marathon had finished at the White City stadium. However, Piercy was not a fraudster. She had set out to run from Windsor to London and she accomplished the feat. Moreover, she ran the twenty or more miles in everyday walking shoes with a crossover strap and heel and her only sustenance was a glass of water and some lumps of sugar.

The reaction to this innovative sporting achievement was mixed. As a sensational news item, it made the newspapers, radio and cinema newsreel. But as an expression of female athleticism, it was heavily criticised. The Westminster Gazette, the same paper that reported the run with enthusiasm, used its editorial page to condemn it:

The Marathon Girl

Miss Violet Piercey must be congratulated as having proved her ability to run well over the ‘Marathon’ course from Windsor to London, but it must be hoped that no other girl will be so foolish as to imitate her. It has been made clear lately that athletic ability is not entirely confined to men, though the men, as can be only expected, are still far in advance of their feminine rivals. But there are obvious considerations which suggest that girls and women should be discouraged from attempting feats of endurance, which place a great strain not merely on the heart, the lungs and the muscles, but on the entire System. What happened to the first ‘Marathon winner’ is a matter of tradition and only a few years ago we saw Dorando nearly kill himself in performing such a feat. For women it ought to be prohibited.

Another journal, All Sports Weekly, which in view of its inclusive title might have been expected to show approval, wrote:

When it comes to a woman running a Marathon course of twenty-six miles, as a Miss Piercey, of London, did the other day, thousands who have an open mind on the value of athletics will join the objectors. The Marathon should be cut out by the women.[v]

The runner herself was unrepentant. Five days after her run she was broadcasting to the nation a ten-minute talk, My Run from Windsor, on BBC 2LO radio:

We are only at the beginning of the new epoch of women athletes. It is not so long since we moved about in crinolines and stays, but I feel sure that the cult of athletics among women can do nothing but good, and will tend towards producing a race of women capable of and suited to motherhood. At the basis of all athletics is rhythm, co-ordinated movement and clean living, and the parents who encourage their daughters to take up athletics will help them to become good citizens.[vi]

Daily Mirror – Monday 28 May 1928

Clearly, Piercy already saw herself as a spokesperson for female athletes. The mention of motherhood shows she was aware of the widely held view that sport taken to excess was detrimental to childbearing. As her career progressed, she would often give quotes to the press about the benefits of athletics. Unfortunately the above is the only section of the talk that has been traced. The BBC have confirmed from their files that the broadcast was “a late topical insertion into the schedule.” They must have had confidence that this unknown runner was capable of putting together a ten-minute talk and delivering it in the acceptable accent of the time.

The cinema, too, celebrated the run. A British Pathé clip[vii] that can still be viewed on the internet, entitled Miss Violet Piercey the Long Distance Runner, carried the caption:

Anyone here like to run 26½ miles non-stop? This lady did from London to Windsor in record time (for a lady). ‘There’s nothing like skipping to keep you fit,’ said Miss Piercey. ‘But there’s only one way of reducing the 3 hours 40 minutes I took on my last record – more running.’ And our slow camera agreed.

She is seen running on the road accompanied by a car and three male cyclists; skipping on an athletics track; running on the track; and with head and shoulders facing the camera. She is wearing the low-heeled, cross-strap shoes that she seems to have favoured throughout her ten year career.

The Pathé caption-writer made some errors, apart from the spelling of the surname. The run was not from London to Windsor, but the reverse. More unfortunate was the assertion that the distance was 26½ miles. This, and reports in some of the press, gave credence to the idea that Violet had run the full marathon distance and more. It was probably beyond her power to correct the impression and she may not have appreciated its historical significance. So far as she was concerned, she had completed a marathon from Windsor to London and that was her claim to fame. No statement from her correcting the distance she covered in 1926 has been traced. However, the wish to prove herself over the full distance may have been why she persisted with her solo runs for another ten years.

Sunday Mirror – Sunday 24 July 1927

The Lone Long Distance Runner

The rules of the governing body, the WAAA, meant that distance running by any woman would have to be performed in isolation. Cross-country running was tolerated, but not the sort of road running Violet did. This resulted in a bizarre situation. In 1927, she was invited by the organisers of the August Bank Holiday British Games, one of the major men’s meetings of the year, to appear at London’s Stamford Bridge stadium in:

Event 19, 10 miles Run by Miss V.Piercey, London Olympiades. The Course will be a measured one, five miles out and home on the official Marathon course, including one lap on the track at the start and the finish. Last year Miss Piercey accomplished the remarkable performance of running from Windsor to Battersea.[viii]

She went off at 4.15 and was scheduled in the programme to arrive at 5.30. This she accomplished in pouring rain, almost to the minute, finishing in 1 hour 13 minutes.[ix]

In September, before a smaller crowd, she ran a solo 12 miles at the Staines Police Sports in 1 hour 39 minutes 15 seconds. The West Middlesex Times commented:

Her mode of progression was not impressive, a kind of steady trot, and after completing a lap of the course she disappeared into the country with a cyclist as pacemaker. At the conclusion she appeared perfectly fresh and ready to reel off another 12 miles.

It has to be said that Piercy was always more of a jogger than a racer, but of course she could have no conception of what was physiologically possible. She ran for endurance, without competition.

She said before starting another ten mile run the same year, this time entirely on the roads, starting from Big Ben:

“I am about the only long-distance woman runner in this country, and people rather shout at me about it. I really don’t see why they should. Running is about the healthiest form of exercise a woman can have, especially in these days of the ‘slimming’ craze. A girl will cheerfully run – for that is what it amounts to – miles and miles in dance-halls and yet shrinks from the idea of running on a road, which is far healthier and quite as effective.”[x]

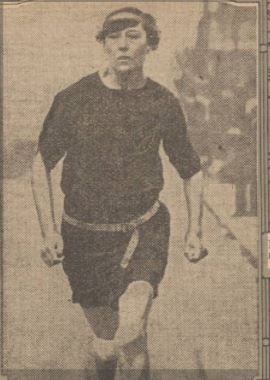

Miss Violet Piercy

Nottingham Journal 8 September 1927

The WAAA now took a contrary view. Major Marchant had been replaced as honorary secretary by a Mrs L.Goold. The Daily Mirror reported on 22 May, 1928:

One hears a lot of gossip as to a desire among women athletes for races on the road, but I am assured by those in authority that there is not likely to be any development in that direction. Mrs Goold, the Hon. Secretary of the Women’s Amateur Athletic Association, tells me the Association is directly opposed to road racing, and to events of inordinate distance anywhere.

Piercy was evidently unimpressed, for only a week later, on Whit Monday, 29 May, she attempted another solo marathon, this time over the official course used on the Saturday for the annual Polytechnic Harriers race. But the weather was unseasonably warm, rising to 79 degrees/26 C. Under the headline A Gallant Failure, the Daily Mirror reported:

The heat was responsible for Miss Violet Piercy’s failure to beat her own record for the Marathon course from Windsor to London yesterday. After 3 hours 31 minutes, when she had covered 20 miles by beautifully rhythmic running, she had to give up. It was a gallant failure but I am confident, as she herself is, that she can set up a magnificent record that will long stand.[xi]

It appears that with this run Piercy had intended to answer all doubts about her previous Windsor to London “marathon” by running the full distance over the same course as the men. Her time for the 20 miles she completed tends to confirm that the 1926 run in 3 hours 40 minutes had been closer to 20 miles than 26.

She composed yet another press statement banging the drum for women in sport:

People often think that a sporting girl is ungracious. Don’t you believe it. Is there any argument why a girl should not be able to run like a deer and still be a dear? Most of the girls I know are athletes. They like dancing and parties. So do I, but we don’t live for them. Neither do we spend our time powdering our noses in musty boudoirs. We like as much fresh air as we can get. That is the great difference. Many men – and women too – think that girl athletes are of no use to the home and that they fail to make good mothers. Sheer bunkum![xii]

Piercy versus Coplans

There is a dearth of reports of Piercy’s running during 1929-1932, and this may well have been because she was involved in litigation. As far back as 1923 she had become the patient of a Dr Eric Coplans, who had a practice in Battersea. They got on well, the doctor introduced Piercy to his wife and it turned out that the two women had been involved together previously in amateur drama. Then Coplans offered to invest £100 of Piercy’s money. This proved unwise. When, after a year, she asked if she had earned any interest, Coplans offered instead to employ her as his secretary for £2 per week and to teach her dispensing and nursing. In the first two years he was continually borrowing money from her (between £400 and £500) and paid her no wages. Only in 1926 did Coplans begin paying the £2 wage. In 1930 he was declared bankrupt.

There was worse. In September, 1929, Coplans said to a colleague in Piercy’s presence, “She is a blackmailer and is blackmailing me. It is a long story and I can’t tell you all now.” He repeated the accusation on two other occasions. Piercy brought an action for slander. [xiii]

Nottingham Evening Post 26 October 1932

It emerged from the subsequent court proceedings that Piercy was heavily involved in litigation at this time. She had brought four actions against Dr Coplans, including one for assault, and she also sued a Mr Percy for assault and for obtaining money from her under promise of marriage.

The action for blackmail finally reached the High Court in October, 1932. There was little prospect of Piercy profiting. Her counsel, Archibald Safford, stated that she had brought the action only to uphold her honour. Mr Safford said his client was “of some repute in the athletic world”, which was true; and that “in 1926 she won the Women’s Marathon Race from Windsor to London and she had also won other long-distance races” which was not strictly true. Dr Coplans, conducting his own case, picked up the inaccuracy: “I suggest you have never won a marathon or long distance race.” Piercy replied, “My counsel did not understand. They were records I made.” Later, Coplans questioned Piercy about her behaviour:

’Have there been times when your conduct has caused me considerable anger?’

‘No.’

‘In the presence of my patients have you not screamed, made accusations and threatened me with disaster?’

‘No.’

‘Have you not paraded in front of my surgery?’

‘Never.’

‘And endeavoured to stop me driving away in my car and clinging to the footboard?’

‘No. When I drove with you it was at your own request.’

‘Did you instruct your solicitor to begin an action against Mr Percy for obtaining money from you under promise of marriage and for assaulting you?’

‘Yes.’”[xiv]

Dr Coplans denied that he had uttered the slander complained of, and then undermined the denial by adding that if he spoke the words they did not bear the meaning the plaintiff imputed to them, but that they were merely words of abuse spoken in heat and uttered in anger.

The jury found in Piercy’s favour. She was awarded £200 and costs. It is doubtful whether she ever received the money and it must be an open question whether her honour was fully upheld. However, she gained more publicity over the case than she had for any of her runs. All the national papers including The Times gave prominence to the story and it made the Evening Standard front page headline: £200 SLANDER DAMAGES FOR WOMAN ATHLETE.[xv]

It may be noted that the assertions, which Piercy denied, about her making scenes in and outside the surgery have an echo of the conduct of her mother Louisa in Croydon twenty-four years earlier.

Article © of Peter Lovesey

Catch up on the final part of this article next week here on Playing Pasts

References

[i] The Times 27 October, 1932

[ii] Evening Standard 26 October 1932

[iii] Daily Express 18 January 1902

[iv] Ibid 16 September 1902

[v] All Sports Weekly 16 October, 1926

[vi] Essex Newsman, Points from talks broadcast, 16 October, 1926

[vii] www.britishpathe.com/video/camera-interviews-the-runner

[viii] British Games programme, 1 August, 1927

[ix] Daily Mirror 2 August, 1927

[x] The Advertiser, Adelaide, Australia, 17 September, 1927

[xi] Daily Mirror, 29 May, 1928

[xii] Telegraph-Herald & Times Journal, Iowa, 15 July, 1928

[xiii] The Times 27 October, 1932

[xiv] Evening Standard 26 October, 1932

[xv] Ibid

Wonderful piece on Violet Piercy, marathon runner. I noticed a few anomalies: if Louisa and George, Violet’s parents were married in 1886, Louisa was 35 and George 65 then Louisa must have been born no later than December 1861 not 1863. If George was born in 1833 he would have been 57 not 68 when violet was born. Louisa was 48, as she stated, not 59 on the 1911 census.

Correction: if Louisa and George, Violet’s parents were married in 1886, Louisa was 35 and George 65 then Louisa must have been born no later than December 1851 not 1863.