How do you sell a sports paper? How do you convince potential readers that your paper is a better buy than the other titles on offer at the newsagent’s? To make the difference, you need a good sales pitch. In this article, we look at how devising such a pitch already preoccupied sports journalists in the early twentieth century.

As in most of Western Europe, sports were becoming a popular pastime in Belgium just before the Great War. Football appealed to an growing number of the bilingual country’s Dutch-speaking Flemings and French-speaking Walloons, as did boxing, while cycling was on a fast-track to becoming the nation’s number one sport. But sports were not only becoming a popular pastime, it was becoming a business. Newspaper owners realized sports news sold copies, and began to capitalise on that discovery. In Flanders, the years between 1908 and 1910 saw an explosion of new sports titles like Sportman, Sportblad or Sportvriend. On 12 September 1912, Sportwereld joined this growing market. Like many of its colleagues, the new paper focused especially on cycling. The paper did well. Before the outbreak of war in August 1914, Sportwereld had overpowered its competitors, becoming the leading Flemish sports paper. How did they do it? Its considerable financial backing played a role, to be sure. But that was not all. In every issue, Sportwereld’s journalists also told its readers why they were the best in ways that were both subtle and explicit. How they did this, tell us a lot about the paper’s marketing tactics, but also about what its contributors saw as good sports journalism.

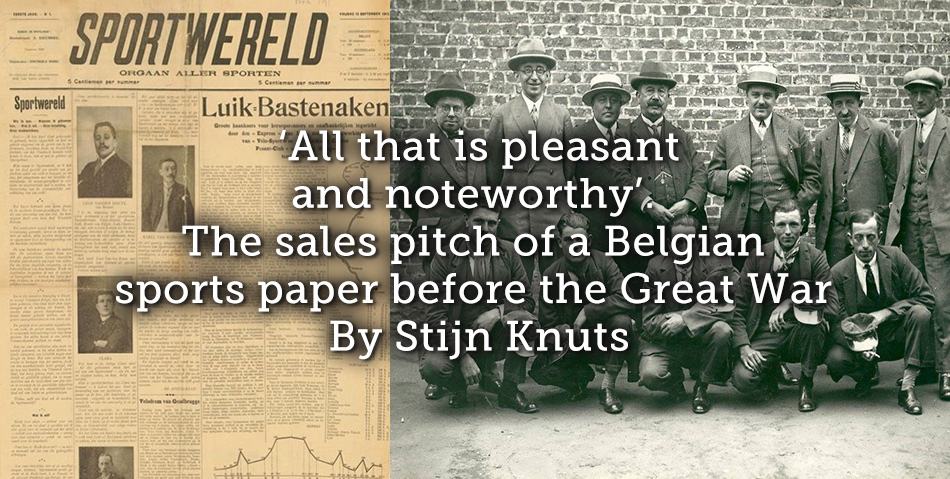

- Sportwereld’s first ever issue, published on 12 September 1912

News from those who know

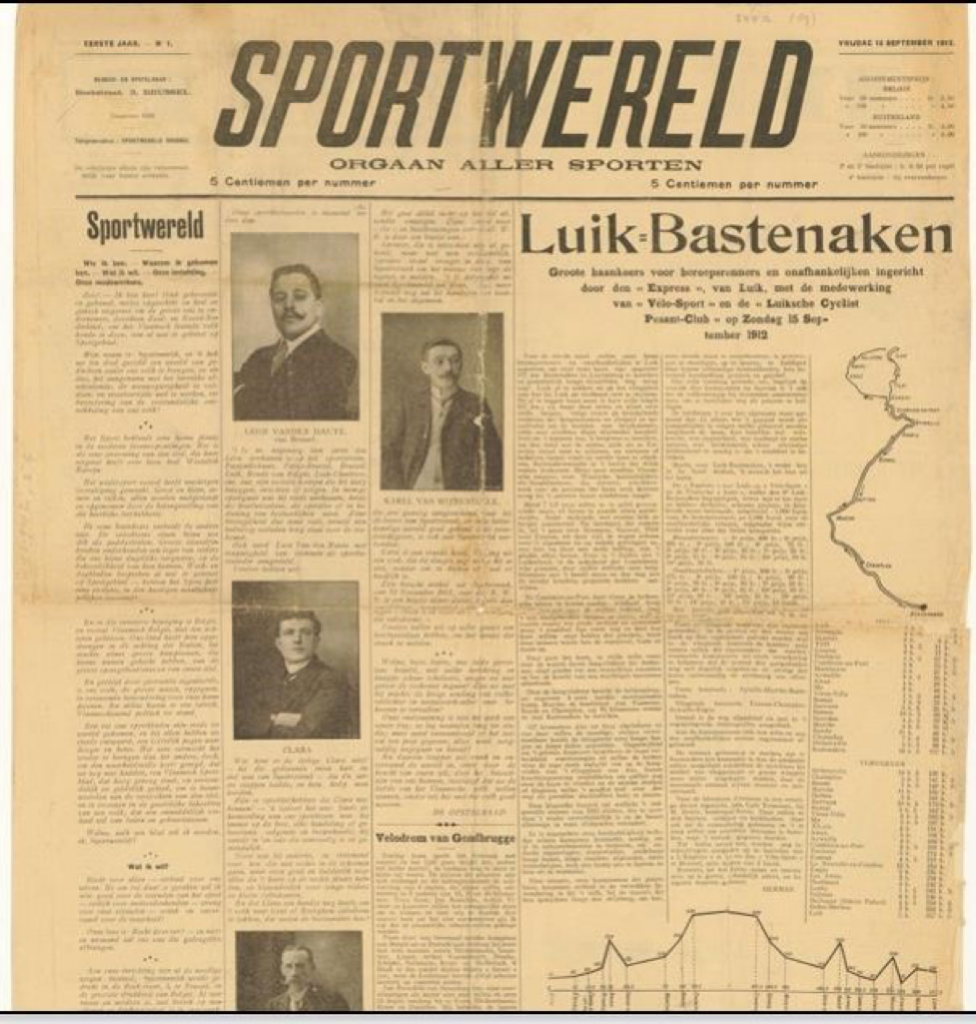

First of all, Sportwereld consistently emphasized how it got its news first-hand by sending its reporters wherever the action was, whether it was a big football match or Brussels’ six days bicycle races. In truth, the paper had only a small team of core contributors – as did most Belgian pre-war sports titles. Only a handful of them worked for the paper as full-time professionals, like its director Léon Van den Haute or its editor-in-chief Karel van Wijnendaele did. But the part-time correspondents it employed in many Flemish regions and small towns also allowed it to boast of how even its reports of regional sporting events came straight from the horse’s mouth.

- Sportwereld’s team of reporters in the 1920s. Director Léon van den Haute is on the front row, third from the left. Editor-in-chief Karel van Wijnendaele can be seen on the same row, fifth from the left

Not only, Sportwereld claimed, was it present everywhere sports were being played. Its journalists also observed everything they saw with the knowledgeable gaze of the seasoned sportsman. Especially editor Van Wijnendaele’s expertise in cycling was highlighted. In January 1914 for instance, an announcement that Van Wijnendaele would personally report on the Paris six days race stated that he, ‘with his expert eye, will notice more than one detail that would escape other, untrained ones.’ To be sure, Sportwereld’s contributors were often well versed in their sport of choice. Van Wijnendaele had been a cyclist himself and was involved in managing both cycling tracks and individual racers. But it was the continuous flaunting of this expertise that mattered here, making it into a marketing tool and a claim to journalistic legitimacy.

Two local correspondents in the picture. Sportwereld regularly featured their photographs and biographies, conspicuously stressing their sporting credentials while doing so

While Sportwereld emphasised the omnipresence and expertise of its reporters, there was one thing that was even more important: speed. The introduction of telegraph and telephone in the nineteenth century had made timely reporting essential to the press. The paper to first publish a story had the advantage over its competitors. This especially rang true for sports, as getting match or race results to the public first guaranteed high sales. For this reason, Sportwereld proudly reported on every instance in which it managed to provide news on a very short notice. In June 1913 for instance, it featured a ‘spontaneous’ letter of a group of readers who praised how Sportwereld had provided them with the results of the Paris-Roubaix cycle race only 28 minutes after it had finished. On March 14, the paper even boasted of how it had distributed a partial report on its own Tour of Flanders race only minutes after it ended, claiming to have set a record ‘in american style’.

Better than all the rest

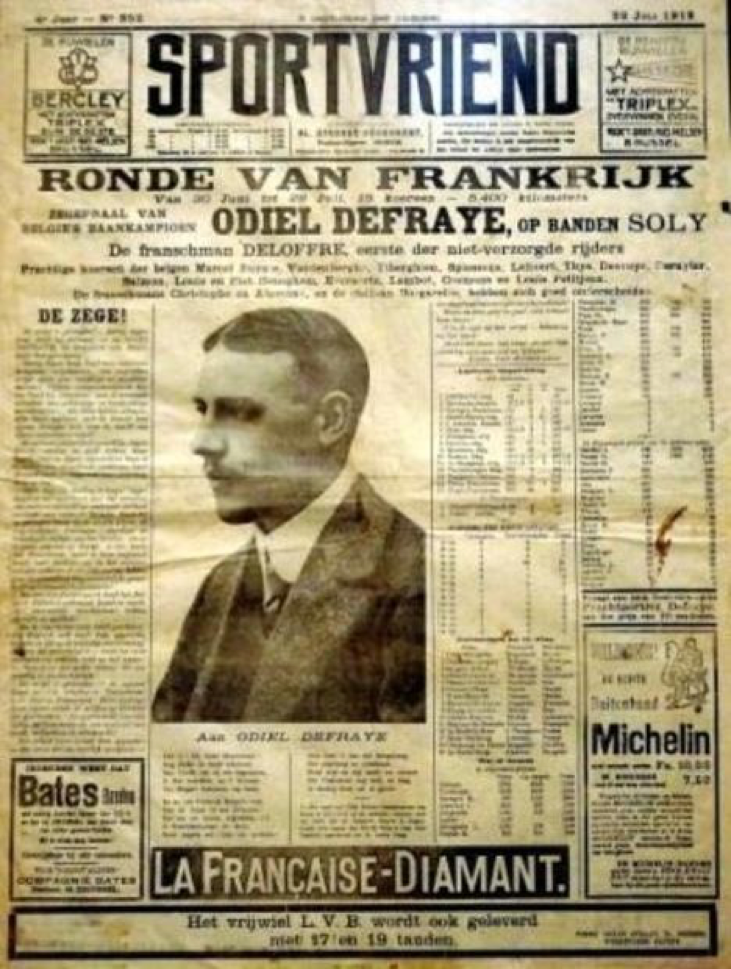

Telling your readers you were fast and observant was a good strategy. Telling them your competitors were the exact opposite was an even better one. Sportwereld was part of a young but competitive sports press market, and its editors let no opportunity slip to take jibes at its rivals by favourably comparing its own standards of journalism to the latter’s. Especially its conflict with the older paper Sportvriend illustrates this. As papers which both focused on cycling and were based in the western part of Flanders, they vied for the same readers. Understandably, Sportvriend feared the loss of its strong market position to the newcomer. For Sportvriend’s director Alois Strobbe things were also personal, as several of his best reporters had left him for Sportwereld. Little surprise, then, that both papers engaged in a months-long war of words from early 1913 on. Sportwereld often used satire in this conflict. In February 1913 for instance, it ridiculed Sportvriend in a lengthy, front-page report of a fictional cycling race, the six-days of Iseghem – the town where Sportvriend was printed. At other times things got more vicious, with personal attacks on reporters flying both ways.

- A front page of Sportvriend. Founded in 1909, it was Sportwereld’s biggest rival

Whether it struck a humorous or a serious tone, Sportwereld constantly jabbed at the failing journalistic values of Sportvriend. Most of those working for the paper were laughed at for lacking expertise, having taken up sports reporting only to make money or on a whim. Hence, Sportwereld claimed, Sportvriend seldom had good eye-witness accounts, but mostly copied information from other papers. Because of this, Sportvriend also failed to provide speedy reports. And when it did manage to print an original article, it burst with inaccuracies. Sportwereld gleefully mocked the many factual errors made by one of Sportvriend’s contributors by nicknaming him ‘Tone de Schieter’, or Tommy Misfire. All this, of course, positively contrasted with Sportwereld’s own, self-proclaimed high standards.

- Sportvriend-contributor nicknamed ‘Tone de Schieter’ in a 1913 Sportwereld-caricature. The caption translates as ‘tried (lit. weighed) and found wanting.

A duty to the public

At its core, however, Sportwereld’s sales pitch did not hinge on telling its readers how it was better and faster than the rest. A more fundamental argument ran through all this boasting. Sportwereld did not just sell sports news, it went: it fulfilled a duty towards the public. The public wanted sports news. By providing this in a speedy and accurate way, the paper was giving that public exactly what it wanted. What was more, Sportwereld boasted, it listened closely to what Flemish sporting enthusiasts themselves had to say about their favourite teams or athletes. By holding a referendum on which players should be included in Belgium’s national football team for instance, as the paper did in 1914, or organising its own Tour of Flanders cycling race because Flemings wanted to see their star riders perform in their home region. Sportwereld presented itself as a champion of the people. More than mere commerce, it turned publishing sports news into a social commitment.

- Responses to our pools.’ With small articles such as this one, Sportwereld conspicuously showed off its popularity

Claiming to be a top-quality journalistic enterprise serving the public, lastly, was one thing. But to give weight to such claims, Sportwereld also needed to prove them. This it did by conspicuously highlighting its positive reception among its readers. It regularly printed by stories of how its journalists were cheered at cycling races, how its salesmen couldn’t keep up with demands or, especially, how its circulation numbers were always on the rise. Especially on the occasion of events like the Tour de France, the paper triumphantly touted a daily circulation running into the tens of thousands – a number that was likely much exaggerated. Crucially, Sportwereld interpreted all this as not just illustrating its popularity, but how it was trusted by its readers. Trust, then, became the final element in Sportwereld’s intricately crafted sales pitch. It was a pitch that continued to prove its worth after the Great War, as the paper would go on to dominate the Flemish sports press market for years to come.

Article © Stijn Knuts

Read all about the life of Karel Van Wijnendaele and the Tour of Flanders at http://karelvanwijnendaele.be

Hi – thank you for that – would you like to write an article in English for Playing Pasts on van Wijnendaele – I can then link your blog to the article? contact me on TheWelshTerrier@outlook.com or PlayingPasts.co.uk

Thanks

Margaret, Editor, Playing Pasts