William Snook was one the best runners in the country – but this popular sporting hero had a very dark side. He was scammer, a wife beater and adulterer. He moved to Paris and became embroiled with a notorious criminal and put on trial for a daring bank robbery.

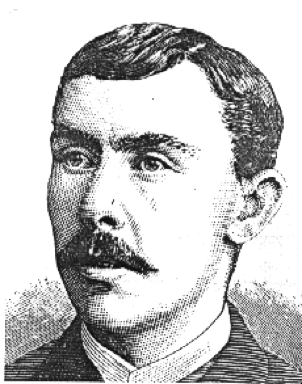

- William Snook

The Little Wonder

He was born in Shrewsbury in 1861 and educated at Admaston College, Wellington. In his teens his athletic ability was clear and he excelled in running longer distances. At one point he’s said to have ran a mile on a stretch of road in under five minutes wearing ‘ordinary shoes’. In the 1880s he won numerous Amateur Athletic Association (AAA) titles with his club Birchfield Harriers and became a household name known as “The Little Wonder”.

The first stain on his character however came in 1881 in a betting scandal when he was suspended for posing as a professional under another name. Other athletes were warned not to compete against him or face sanctions themselves. This lasted until 1882 when he was allowed to compete again.

He continued to win races and national championships and his rivalry with another runner called Walter George became famous. When George quit the amateur competition to turn professional Snook enjoyed even more success. But it wasn’t long until he got involved in another betting scandal.

In 1886 he was banned for life from the amateur competitions for throwing a race and coming second despite being in “splendid condition” and much superior to the winner, Hickman of Godiva Harriers from Coventry. He claimed he was innocent and put the losses down to being underweight and having sore feet. He had lots of support among his fellow athletes and the public – but the authorities didn’t believe him and wanting to clamp down on corruption in the sport which was rife, they banned him.

This forced him into the professional ranks and he continued to complete with some success. Still a popular attraction at races he also became landlord of at least a couple of pubs in Birmingham.

A VIOLENT HOME LIFE

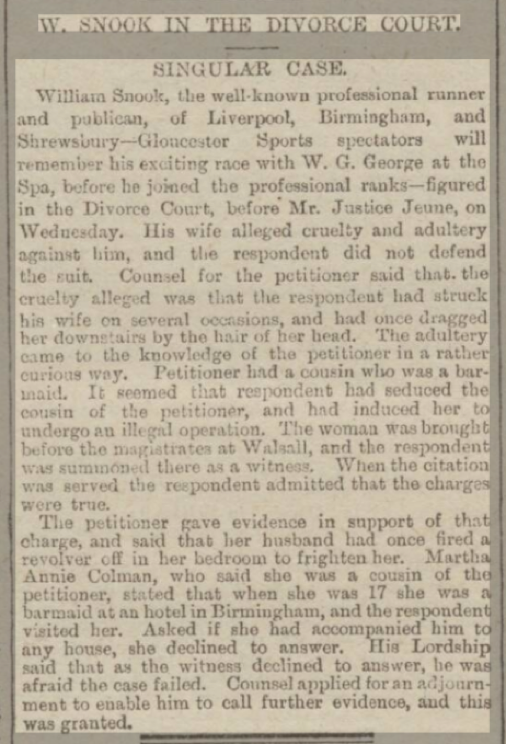

But his public image was vastly different from the private reality and things took a darker twist. He’d married a Liverpool girl in 1884, Elizabeth Jane Coleman, and they lived in Shrewsbury. They had two children who sadly died in infancy. But his cruel ways became public knowledge when the truth of her horrific life with him came out in their divorce hearing in 1892. The court heard that he beat her regularly and once dragged her downstairs by her hair.

- Gloucester Citizen Thursday 16th June 189

His cruelty not stopping there – he had an affair with his wife’s 17 year old cousin Martha Annie Coleman, a barmaid, and then forced her to have a backstreet abortion. He even shot a revolver off over her head in the bedroom to scare her. Snook offered no defence and the divorce was granted. Elizabeth died in Shrewsbury, a single woman, in 1900.

ESCAPE TO PARIS AND A DARING BANK ROBBERY

For whatever reason, whether to escape from his past or seek out a fresh start Snook moved to Paris. His running skills proved vital and he became a coach at a top racing club in the city, apparently having a significant impact in the development of French athletics. But his attraction to trouble proved irresistible.

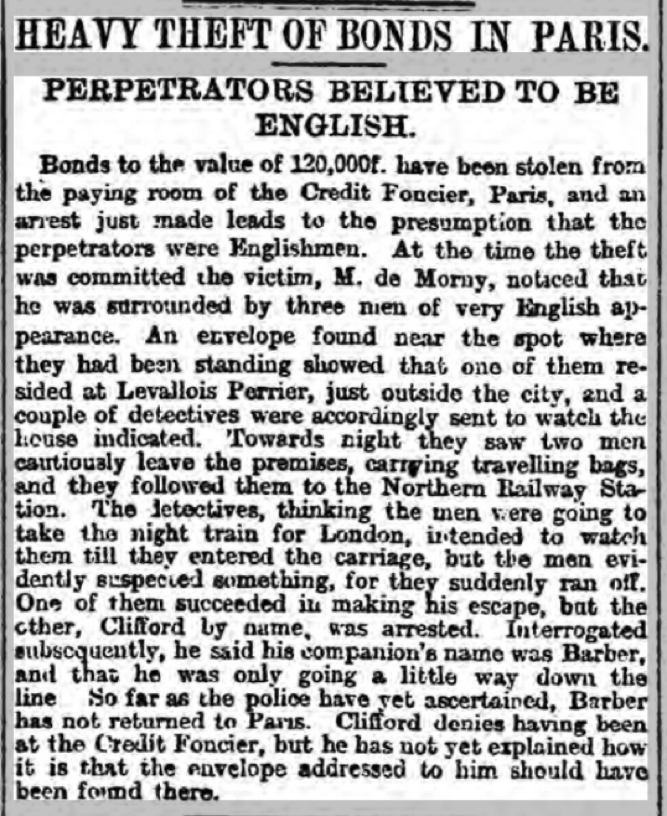

- Sheffield Independent Wednesday 18th September 1895

In early September 1895 three Englishmen entered the Credit Foncier bank in Paris and waited. Their victim, Monsieur Eugene Joly de Morny, was withdrawing a large amount of cash, some reports saying as much as 140,000 francs. As it was handed over one of the men distracted de Morny and the others grabbed the money and they all made a dash for it. However, a crucial clue was left behind – a letter addressed to a man called Clifford. That night police watched Clifford’s house until they saw two men “cautiously leave the premises carrying travelling bags” and head to the train station. The detectives believed the suspects were going to take the night train and so they waited to watch them enter the carriage. But the suspects became spooked and suddenly ran off. The detectives gave chase and were able to catch one of them – Clifford. He denied any knowledge of the bank robbery but gave no explanation as to why a letter addressed to him was left at the scene of the crime.

Clifford, one of his many aliases, was a career criminal. He came from England where he’d carried out strikingly similar crimes, roping in other dodgy characters to help in is dirty work. A well handled and notorious crook, he’d spent time in jail in both England and France. In 1869 he was sentenced to 12 years in prison for a conspiring to steel a diamond bracelet in London. He told the police that the other man, who’d escaped, was called Barber. The detectives bided their time and continued to watch Clifford’s house in the hope his accomplices would return – and one did.

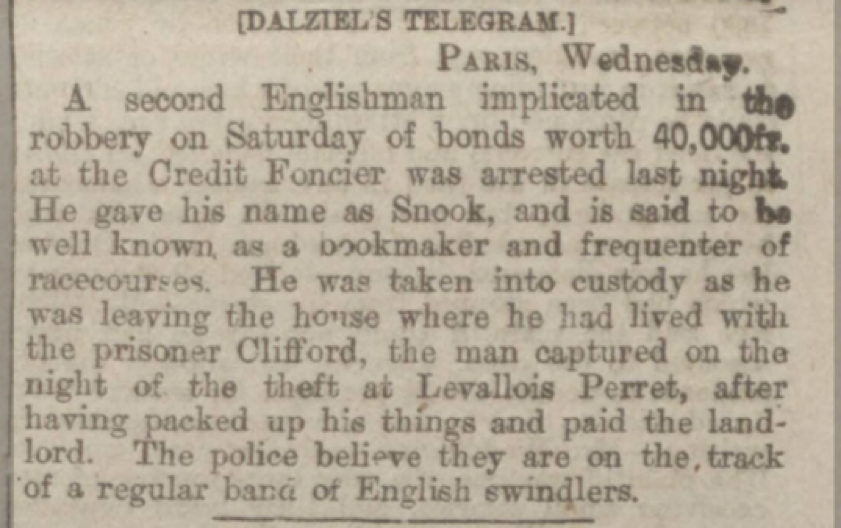

- Nottingham Evening Post Thursday 19th September 1895

A few days later Snook, “a bookmaker and frequenter of racecourses”, was at the house. It turns out he’d been living there with Clifford. He packed up all his things and paid the landlord – presumably aiming never to return – but was arrested as he left. Both were charged with the bank robbery and put on trial. Police believed they were firmly on to the band of “English swindlers” who’d been targeting another of banks across the city in the same manner that summer, and they thought they had two of the main players.

Clifford, whose real name was Matthew Parry, was found guilty and jailed for 5 years. However the prosecutors couldn’t make the charges against Snook stick. On Saturday 28th December 1895 it was reported in the Montgomery County Times and Shropshire and Mid-Wales Advertiser that Snook had been found not guilty – a decision which would apparently be “applauded” by all who knew Snook from his racing past “glad to hear that his reputation has thus been cleared”. Snook claimed he was guilty of nothing more than an act of “over generosity” to a fellow bookmaker and had only gone to the property as a favour to pay the landlady rent she was due from Clifford. He’d gotten away with it!

A MISERABLE END

He fell into hard times as World War 1 broke out and in March 1916 his old club, Birchfield Harriers, heard about his penniless state and ill health in Paris. He’d lost his job and was facing starvation. They made a public appeal for money to help bring home the man who they still admired.

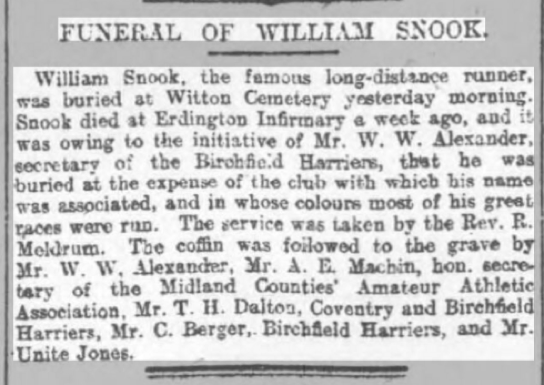

- Birmingham Daily Post Monday 18th December 1916

He returned home but died in a Birmingham workhouse. His family were either unable or unwilling to pay for his funeral and he was buried in a common grave at Witton Cemetery, paid for by Birchfield Harriers; “the club in whose colours most of his great races were run”.

Article © Richard Tisdale

Reproduced by kind permission of the author

See blogsite – https://newsfromthepast.blog