Newmarket’s Jockey Club rooms are world-famous amongst lovers of racing. If you can afford it, you can have a private tour for your group, which will include humorous tales of the rich and famous and their racing lives, and can also include lunch, afternoon tea or dinner. Ever since Charles II started racing there, Newmarket has been the vibrant heart of thoroughbred flat racing. By the 1870s the Jockey Club had established control of flat racing at all the major courses.

The Newmarket Jockey Club, racing’s own historians and sports historians alike have all long believed the Jockey Club to have been founded in the 1750s. Back in 2002 the Jockey Club proudly celebrated its 250th anniversary with a special race at the Craven meeting. This date was chosen because in 1752 Pond’s Sporting Kalendar had announced a forthcoming Newmarket race to be run ‘by horses ‘the property of the noblemen and gentlemen of the Jockey Club at the Star and Garter in Pall Mall’. The Jockey Club website and Wikipedia suggested a date between 1750 and 1752 as the date of the Club’s founding. Wray Vamplew, in his book The Turf(1976) was a little more cautious, saying ‘it is not known when exactly it was founded but it was probably in 1751 or 1752’ In my book Flat Racing and British Society (2000) I suggested that it was founded ’before 1752’

- ‘The Duke of Hamilton’s Grey Racehorse ‘Victorious’ at Newmarket’, John Wootton (1682-1764) c. 1724 Courtesy of the Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

We all took this date as a reasonable approximation. But in recent years eighteenth century newspapers have increasingly been digitized and made available on line, and my first searches in 2012 showed, to my surprize, that there were much earlier references than had been thought to a Newmarket Jockey Club, going back to the 1720s, 1730s and 1740s and referred to meetings at other coffee houses in London, with overlapping membership to the 1750 Club, and identical interests in Newmarket racing.

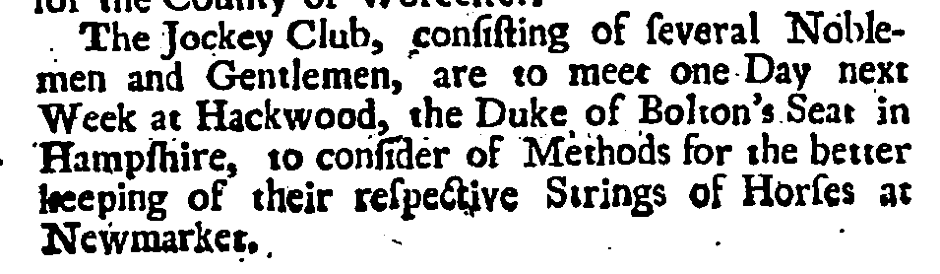

In 1729, for example, newspapers reported that ‘the Jockey Club, consisting of several Noblemen and Gentlemen’, were to meet one Day the following week, ‘at Harkwood, the Duke of Bolton’s seat in Hampshire, to consider of Methods for the better keeping of their respective Strings of Horses at New Market’. Thereafter there are very occasional, very brief press mentions of a Jockey Club which maintained Rooms in William’s Coffee (and Chocolate) House in St James, a fashionable area close to the heart of government in London.

- Daily Post, (London) Saturday August 2nd 1729

These meetings at coffee and chocolate houses were normal for the time. Even for the rich coffee and chocolate were luxury drinks. They were imported from far away, and were very expensive. The coffee houses in London and other large towns were the meeting places for the same fashionable groups who owned racehorses and ran them at Newmarket.

Charles Powlett, the third Duke of Bolton, appears to have been a major force in the organisation. In 1729 he was the principal landowner in Hampshire, Lord Lieutenant of the County, Governor of the Isle of Wight and Colonel of the Royal Horse Guards. He also had estates in Wensleydale in Yorkshire, famous still as a breeding, training and racing area. Around 1729 he was a leading racehorse owner, who raced his horses at Newmarket in the two major meetings there, when racing took place over the months of April and October. Born in 1685, he was reputedly frivolous, weak, a libertine and gambler. Around 1729 the Duke, along with the Earl of Godolphin, the Earl of Halifax, Sir William Morgan and Mr Panton, raced his horses at fashionable Newmarket more regularly than the forty or so others whose horses raced there. So these men may also have been Club members.

But if the Duke was the leading light of the Club, his light was fading, as he suffered from ill-health. On 27th January 1733, for example, the Newcastle Courant reported that though he was to dine on the following Monday at Williams Coffee House, he had been ‘dangerously ill’ but is ‘pretty well recovered’.

In the late 1730s there were growing anxieties about renewed Catholic and Jacobite support for the Stuart king in exile, Charles Stuart. And horse racing for small prizes was flourishing throughout the country, encouraging idleness. So Jockey Club members like the Duke were behind a successful Act (13 Geo. II. c. 19 (1740)*13, 141–2) which forced many meetings out of existence, insisting that that any race should have a prize of at least £50. The numbers of race meetings in Britain decreased immediately. Unfortunately it affected Newmarket too, with far fewer entries and races. By 1742 the Duke was only racing one horse, Sour Face, and it ran at Winchester, Canterbury and Salisbury, and not at Newmarket. Newmarket struggled. So presumably did the Club.

This new information about the Club shifted my research backwards into the seventeenth and eighteenth century and led me to write my monograph: Horse Racing and British Society in the Long Eighteenth Century (Woodbridge, 2018). The American researcher Richard Nash analysed this early phase of the Club in detail, linking it to elite political interest groups with shared Protestant religious beliefs, many of them Whig political leaders, who associated together early in the eighteenth century, and has suggested that the Club’s formal founding was probably in 1717, when the Hanoverian protestant king George I visited Newmarket. He also offered a tentative list of its leading figures. Wikipedia and the Jockey Club now acknowledge the Club had an earlier existence.

- George I at Newmarket, 4 or 5 October, 1717′, John Wootton (1682-1764), c.1717 Courtesy of the Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

But there are still unanswered questions. For example, was the c.1750 Club a continuation of the earlier Club? Or was it a re-launch, after the first Club had ceased to exist in the 1740s? This is still a puzzle. The doings of the Club were only rarely reported in the press, and little archive material survives relating to landowners’ racing involvement during this period. That makes the organisation difficult to trace over time. What is certain is that by 1751 the Jockey Club rooms were in the Star and Garter in Pall Mall and not in the St James’ rooms. More information may come to light.

Let’s hope so.

Article © Mike Huggins