Having discussed the precursors to bodybuilding trunks in part one of this series, this post will now delve in to the sport of bodybuilding outright. Beginning with the competitions of the early 1900s, it tracks the evolution of the posing trunks right up to the current day. A story of muscle, extreme dieting and of course, anabolic steroids.

Bodybuilding as Competition

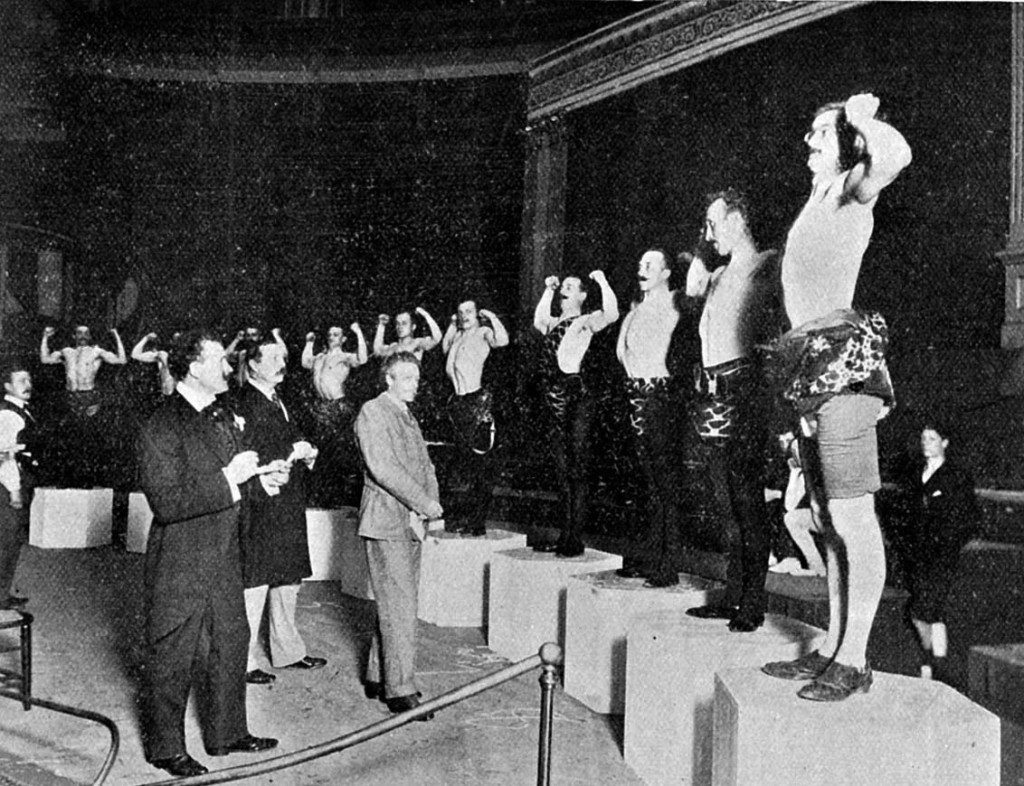

Though private bodybuilding shows had been held in England, France and further afield in the early 1890s, it was not until the dawn of the twentieth century that the bodybuilding or physical culture competition as a public spectacle began to truly emerge. Beginning with Eugen Sandow’s ‘Great Competition’ of 1901 and continuing through the decade, one finds a variety of posing trunks, physiques and styles being displayed for all and sundry.

In the case of Sandow’s ‘Great Competition’, held in London, the Prussian man invited his competitors to compete using loin clothes, tights and posing trunks.

- Sandow’s Great Competition – Inspecting the Competitors, 1901

Sandow’s American counterpart Bernarr MacFadden, who held a similar competition in 1903, echoed this rudimentary bodybuilding uniform. Even more eccentric in his promotion of physical culture, MacFadden’s competition is notable for drawing the ire of morality campaigners within the United States. Though the general British reaction to Sandow’s competition had been laudatory, MacFadden’s was criticised in certain sections for its lurid displays of human flesh, both male and female. Interestingly, there was very little difference in the posing trunks worn either side of the Atlantic. Something evidenced by the remarkable video footage below of MacFadden’s competitors.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SQ89EREzoH0

Whereas Sandow held only one nationwide competition, MacFadden proved to be far more influential, if one accounts for a very prolonged hiatus.

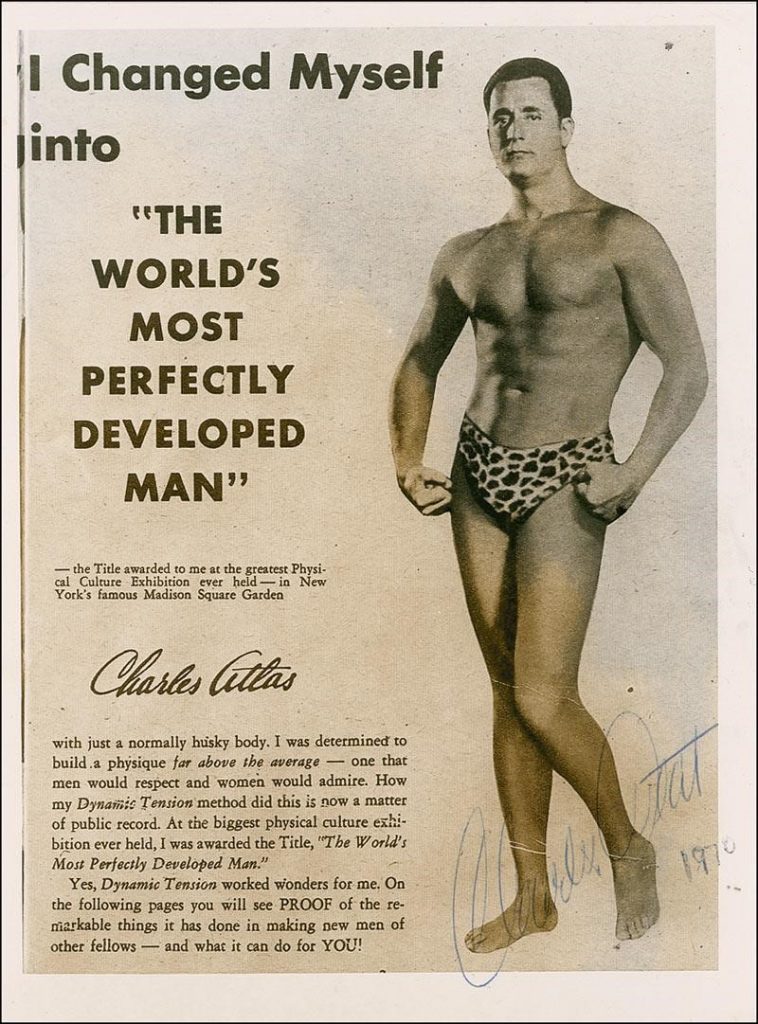

Following the cessation of the First World War, MacFadden initiated a series of physique competitions in the early 1920s seeking to discover the world’s most perfectly developed man and woman. Beginning with a preliminary pictorial competition, a select pool was eventually chosen for inspection under MacFadden’s watchful eye. Over the course of several competitions, one man emerged victorious. Angelo Siciliano by birth, ‘Charles Atlas’ capitalized upon his victories to kick-start one of the most successful mail order businesses of the twentieth-century. A business venture, which remarkably, continues to this very day.

Atlas’s masculine posturing’s within his advertisements featured the Italian émigré in the hybrid loincloth posing trunk, which Atlas had worn in MacFadden’s shows.

- Charles Atlas, Advertisement. Courtesy of charlesatlas.com

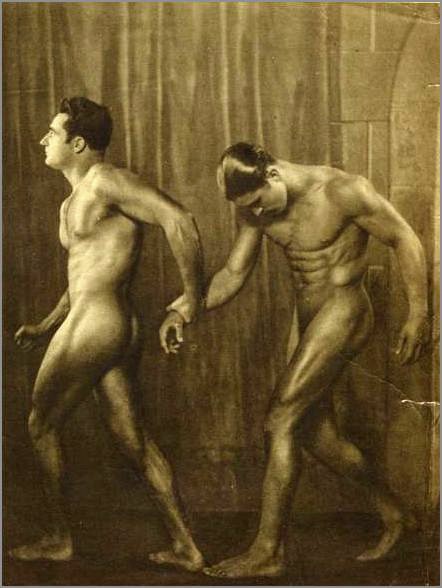

Away from the back pages of comic books and newspapers however, Atlas and others such as Tony Sansome, continued to model using Greco-Roman poses. A reminder that the idea of bodybuilding as art continued in to the 1930s, though in this case without clothing!

- Charles Atlas (Leading) and Tony Sansome (Following), c. 1920s.

Whereas the period up to 1930 had seen physique contests emerge as a largely ad-hoc and sporadic affair, the 1930s saw the pursuit emerge as a form of competition within its own right. In England, Health & Strength magazine sponsored a series of All-Britain Physique Contests. The French Federation of Physical Culture held shows with titles such as the ‘Most Handsome Athlete in France’ and ‘World’s Best Built Man’ competitions. Throughout the 1930s many local and regional weightlifting contests in America included physique competitions under the auspices of the Amateur Athletic Union. This uneasy relationship between the worlds of American weightlifting and bodybuilding eventually led to the breakaway Mr. America contests of the 1940s.

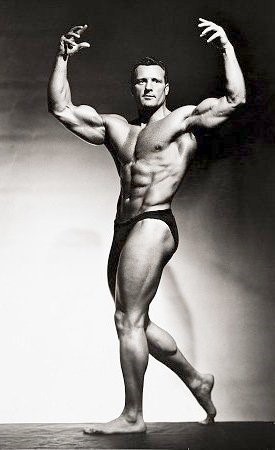

As the sport became more formalized across the 30s and 40s, the standard, de rigour posing trunks became the monotone posing trunks such as those exhibited by John Grimek below.

- Clarence Ross, c. 1940s.

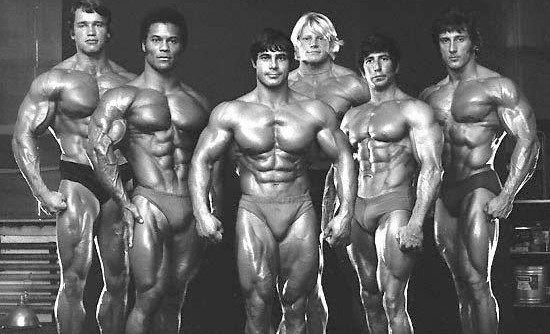

This pattern continued for several decades. Indeed even during the heyday of bodybuilding in the 1960s and 70s, the time of Arnold Schwarzenegger and the ‘Pumping Iron’ franchises, bodybuilders wore the short, oftentimes black, posing trunks. A bodybuilding uniform of sorts.

- Collection of bodybuilders from the 1960s and 70s.

Calories, Drugs and Glutes

The bodybuilding trunks thus remained largely unchanged from the 1940s to 1980s. A static fashion which saw monotone trunks of roughly the same size appear on stages across the planet. Despite the growing muscle mass of the competitors, trunks varied little.

Though enduring for several decades, standard bodybuilding trunks underwent quite a radical transformation during the mid-1980s. Spurred on by a growing obsession with calorie counting and the widespread prevalence of new and powerful PEDs aimed at stripping bodyfat to remarkably low levels, the sport of bodybuilding changed. Competitors were getting leaner and holding on to even more muscle mass. Standards were changing and in a remarkable turn, the gluteus maximus, or ‘ass’ to you and me, became the symbol of leanness.

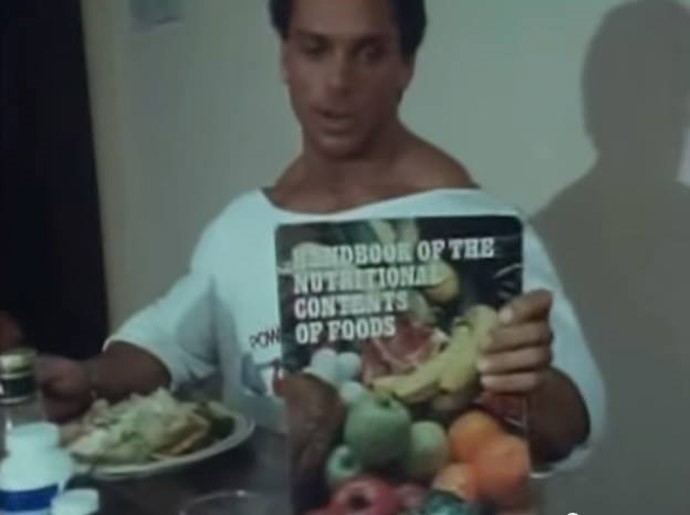

The man responsible for this particular was American bodybuilder Rich Gaspari, whose dieting practices became the stuff of legend. In 1988, Rich Gaspari revealed to the makers of Battle for The Gold, a bodybuilding documentary now available on Youtube, that he calculated his caloric intake to the tee, weighing everything and generally eating an incredibly strict diet. This diet, he attested, was responsible for producing one of the leanest physiques then seen on a bodybuilding stage. How could people tell? Gaspari, unlike his competitors, had stripped his bodyfat to such levels that his glute muscles were clearly visible.

- Rich Gaspari demonstrating his nutritional ‘bible’. From Battle for the Gold.

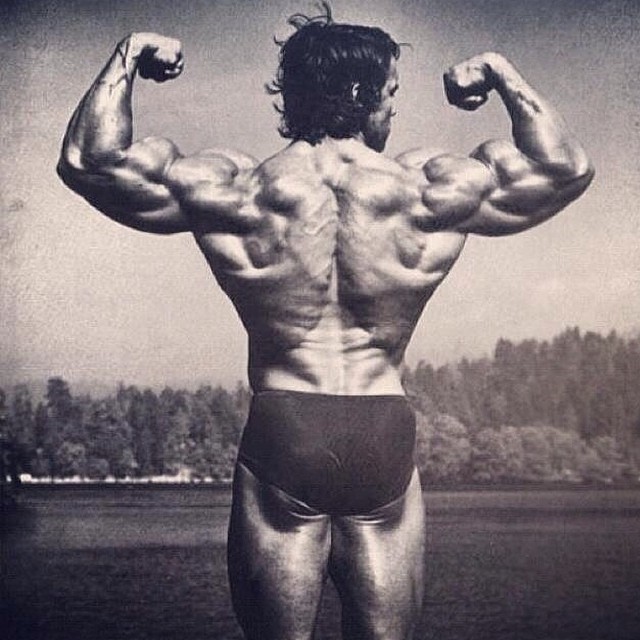

By then Gaspari had clearly demonstrated the efficacy of his approach. In many ways, Gaspari’s calorie counting changed the face of bodybuilding. At the 1986 IFBB Pro World contests, Gaspari revealed his striated glutes to the judges and audience, setting a new standard for leanness that has continued to this very day.

- Gaspari’s Glutes in all their Glory

Gaspari thus set a new standard of leanness for male competitors. Prior to the show, few bodybuilders had attained the low levels of bodyfat necessary to display the glute muscles adequately. Hence, the traditional trunks, covering most of the behind were desirable. As fans, judges and spectators expressed there admiration for the new glute gauge of leanness, bodybuilders were encouraged, especially if they wanted to win, to wear a bodybuilding ‘thong’. Only the ‘thong’ would display their leanness.

- Note the dEight Time Mr. Olympia Champion, Ronnie Coleman, displaying the bodybuildiEight Time Mr. Olympia Champion, Ronnie Coleman, displaying the bodybuilding ‘thong.’

- Note the differences between 00s competitor Ronnie Coleman and Arnold Schwarzenegger who competed primarily in the 1970s. Coleman’s attire highlights his lower bodyfat and increased muscularity.

Backlashes against the Thong

Though the bodybuilding ‘thong’ remained popular, and indeed still is popular in conventional bodybuilding shows, its dominance has waned in recent years. Spurred on by fears of freakish muscle building and dangerously low levels of body fat, the period since 2010 has seen a variety of posing trunks permissible in a variety of competitions. Nowadays competitors can chose from a host of competitions, including but limited to ‘classic’, ‘physique’, ‘fitness’, ‘bodybuilding’ and several other variations.

Interestingly, each division is not without its prejudice. On the terrible confines of humanity that is the internet, those who wear board shorts are mocked for not training their leg muscles, those who wear the bodybuilding thong are attacked for using steroids, those competing in the classic division are critiqued for an overall lack of muscle mass. The clothes make the man, or so it would seem.

- Examples of different shows and trunks. Courtesy of ICN.com.

Wrapping Up

Though the post began by examining bodybuilding as art, commerce and competition, the latter half of the twentieth-century has seen the competitive realm provide the most innovation in the way of clothing. From John Grimek’s traditional posing trunks of the 1940s, the clothes chosen by bodybuilders when stepping out on stage has been subject to a myriad of forces, both sporting and societal.

Regarding the sporting realm, the intensification of bodybuilding competitions has pushed competitors into new, and some would argue, dangerous practices. The bodybuilding thong, used to emphasize striated gluteus maximus muscles being just one example. Another element to consider however is the growing popularity of such shows, especially in the last decade and a half. The proliferation of various competitions (class, fitness, physique etc.) is in part a reflection of the pastime’s growing popularity amongst men in the Western world. A growing number of competitors were ultimately unhappy with the practices and muscularity needed to compete in the traditional bodybuilding world. After much criticism, bodybuilding federations took action and initiated these events, with their own unique trunks of course.

Societally the association between bodybuilding and ‘freakish’ subcultures perhaps explains in part the emergence of the bodybuilding thong in the 1980s. Free from the strictures governing normative ideas of health and some would argue beauty, competitive bodybuilders were granted the space to engage in dangerous methods of lowering their bodyfat. This trend is exemplified by the growing popularity of the bodybuilding thong. Of course, such practices have been spurred on and made permissible by the proliferation of anabolic and other performance enhancing substances within a sport. This relationship began in the 1960s and has grown in strength ever since. Nevertheless the emergence of new competitions, and new trunks, can be seen as a backlash against the muscularity needed to compete in every form of bodybuilding.

Though variable and at times disparate, such trends have influenced how much, and how little clothing has appeared on the bodybuilding stage. For a miserly sliver of clothing, the posing trunks nevertheless have a story to tell.

Article © Conor Heffernan

Sources

Printed Material

Budd, Michael Anton, The Sculpture Machine: Physical Culture and Body Politics in the Age of Empire (New York, 1997).

Chapman, David L., Sandow the magnificent: Eugen Sandow and the beginnings of Bodybuilding (Illinois, 1994).

Forrest, George, A Handbook of Gymnastics (London, 1862).

G.S. Greene and P.A. Marrinan, The Athletes’ Guide to Health & Physical Fitness (Dublin, 1908), 8-9.

Prof Attila, Five Pound Dumbell Exercises (New York, 1913).

Professor Harrison, Indian Clubs, Dumb-bells and Sword Exercises (London, 1865).

Roach, Randy, Muscle, Smoke and Mirrors, Volume One (Bloomington, 2008).

Sachs, Jonathan. “Greece or Rome?: The Uses of Antiquity in Late Eighteenth- and Early Nineteenth-Century British Literature.” Literature Compass 6 (2009): 10.1111/j.1741-4113.2008.00612.x

Todd, Jan. Physical Culture and the Body Beautiful: Purposive Exercise in the Lives of American Women, 1800-1870. Mercer University Press, 1998.

Walker, Donald, British Manly Exercises: in which rowing and sailing are now first described, and riding and driving are for the first time given in a work of this kind…(London, 1834), 26

Web Resources

Battle for the Gold Documentary (Available on YouTube).

Bodybuilding.com

charlesatlas.com

DavidGentle.com

Flexonline.com

ICN.com

Physicalculturestudy.com

Misc

Royal Army Physical Training Corps Museum, Aldershot.

Stark Physical Culture Archive, Texas.

No bodybuilder has ever worn a “thong” in a contest. Some have scrunched up the rear of their trunks at times, but thongs have always been prohibited.