Most South African sport history enthusiasts are familiar with the name Basil D’Oliveria, who was indirectly and unintentionally responsible for South Africa’s cricket isolation. However, few are familiar with William Ronald Eland, better known as Ron Eland – whose significance in South African sport history was made clear by Dennis Brutus’s reference to Eland’s erstwhile coach, Milo Pillay, as the pioneer of non-racial sport. The other, and probably more important, indicator is the fact that he represented England at the 1948 Olympic Games from 9 to 11 August. It is therefore fitting in this Olympic year to take stock of Eland’s multidimensionality as a person and an Olympic athlete.

Eland was born on 28 February 1923 in Port Elizabeth, the cradle of weightlifting in South Africa. The Eland family has an expansive sports history. His father, Andrew Eland, was the secretary of the then Eastern Province Coloured Rugby Union. Ron Eland’s cousin, Cecil February, was a South African wrestler. Another relative, Christie Lyner, was a South African bodybuilding champion.

Eland started this primary school career in humble conditions at Weis Primary School in Port Elizabeth. He obtained the Lower Primary Teacher’s Certificate (Coloured) at Dower College in Uitenhage. His teaching career started in 1943 at De Vos Malan Primary School. On 6 January 1944 he joined the Milo Academy of Health and Strength. This academy, which was founded in 1929 and was affiliated with the international Health and Strength League, was run by Pillay. In 1944, Eland weighed in at a mere 136 pounds (61,6 kg) and could bench-press only 100 pounds (45,3 kg). However, his concentration and scientific exercise methods eventually enabled him to beat his coach, Pillay. On 27 November 1945, during the annual Milo Academy show, Eland, weighing in at 143 pounds (64 kg), bench-pressed 195 pounds (88 kg), which ensured him prominence in weightlifting circles. On 23 December 1947, again at the Milo Academy show, Eland had improved to such an extent that he bench-pressed 210 pounds (95,2 kg). With the support of Matt October’s entertainment abilities, he soon dominated the weightlifting code in South Africa. In the same year, Pillay sent a humble letter to the then South African Olympic governing body with a request to consider coloured weightlifters for the South Africa team for the 1948 Olympic Games. The governing body refused, and chose Piet Taljaard and Issy Bloomberg. Despite this humiliation, Eland and Bloomberg maintained a lifelong friendship. Eland’s way to the Games came through the British Commonwealth ruling that England should be given preference in the choice of athletes from member countries.

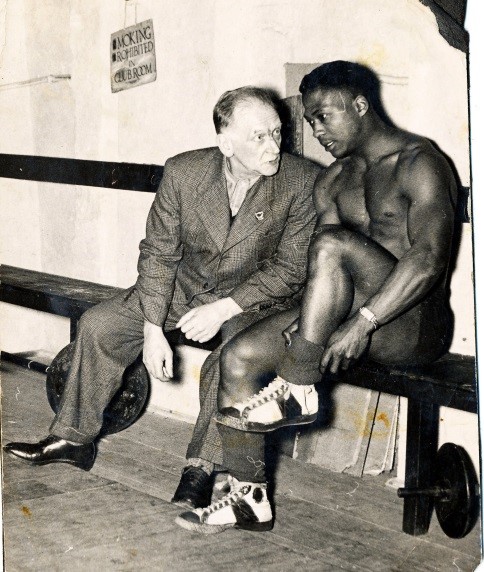

Issy Bloomberg, official South African weightlifter in the 1948 Games, with Ron Eland

Source:Ron Eland private archive

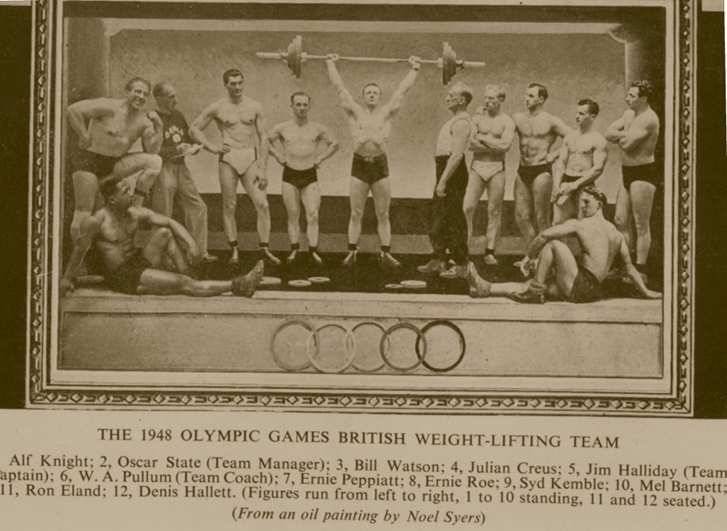

On 6 March 1948, Eland left for England with the financial support of the Milo Academy and the British Amateur Weight Lifting Association (BAWLA). Oscar State, secretary of BAWLA, took him under his wing and Tromp van Diggelen (see By 23 April 2016) organised coaching by William Pullum, a British weightlifting expert. This led to Eland being chosen for the British Olympic team of 1948, although he collapsed during the competition with appendicitis.

William Pullum and Ron Eland during the Olympic Games, 1948

Source: Ron Eland private archive

Together with members of the Wesley Physical Culture Club (WPCC) in Salt River, Cape Town, established by Sid G Rule in 1935, Eland took weightlifting to the national competition level. On 22 August 1950 the WPCC convened a meeting with the aim of establishing a non-racial South African weightlifting federation that would be affiliated with BAWLA and recommend coloured weightlifters for the Olympic Games. In the same year, he qualified as physical education teacher at Wesley College with the Higher Primary Teacher’s Certificate (Physical Education) (Coloured).

During the Cavalcade of Health and Strength event, organised by the WPCC in 1951, the master of ceremonies announced that Eland was invited by BAWLA to participate in the 1952 Olympic Games. However, there was a growing sentiment among the English that British citizens should enjoy preference in team choices – leading to Eland being denied a possible Olympic medal for the second time. Participation in South Africa was not an option due to the colour policies of the South African Olympic Committee and the Commonwealth Games Association. As participant in one of the three Mr Universe competitions at the time, he was however a forerunner of other South African bodybuilders and weightlifters, such as Henry Jones, David Isaacs, Precious McKenzie and Pat Graham, who participated internationally during the apartheid years.

Eland’s sports career was characterised by community involvement. He was a founding member of the Wynberg-based (later Mitchells Plain after the forced removals) Farnese Bodybuilding Club in 1958. Eland was also involved with the Maitland Cottage Hospital, where he assisted with the rehabilitation of disabled children. In 1970 he was initially involved in the coaching of Pearl Jansen, Miss Africa South (a segregated competition organised separately from the Miss South Africa). In that year he left for the USA, and his private archive contains interesting information on his daily experiences and racism there. He settled his family in Canada in 1974 and worked as a sports coach at various institutions, where he applied his knowledge of physical education acquired in South Africa. This led to his appointment as technical coach of the 1976 Canadian Olympic weightlifting team, as well as the Canadian Commonwealth team two years later.

Eland experienced a wealth of opportunities in Canada that he was denied as a racially classified person in South Africa. One such opportunity was the chance to express himself openly, without fear of intimidation, against the apartheid policy on sport. He appeared on Canadian television, where he openly talked about the evils of apartheid. Due to the apartheid policy, which prohibited Eland from higher education in physical education in South Africa, he could not study at a tertiary institution. In Canada, he obtained two university degrees. His life was therefore characterised by humiliation, struggle, perseverance and reconciliation in sports. He died on 12 February 2003 during a visit to South Africa, during which he would have been honoured for his contribution to weightlifting in South Africa. According to Eland’s family, he never bore a grudge against any white weightlifters who excelled at his expense. But this pioneer of weightlifting in South Africa admitted that the humiliation and pain of disparagement never left him.

Ron Eland in the British Olympic team

Source: Halliday, J. 1950. Olympic weightlifting with body building for all. London: Pullum

Article Ⓒ of Fran Copeland