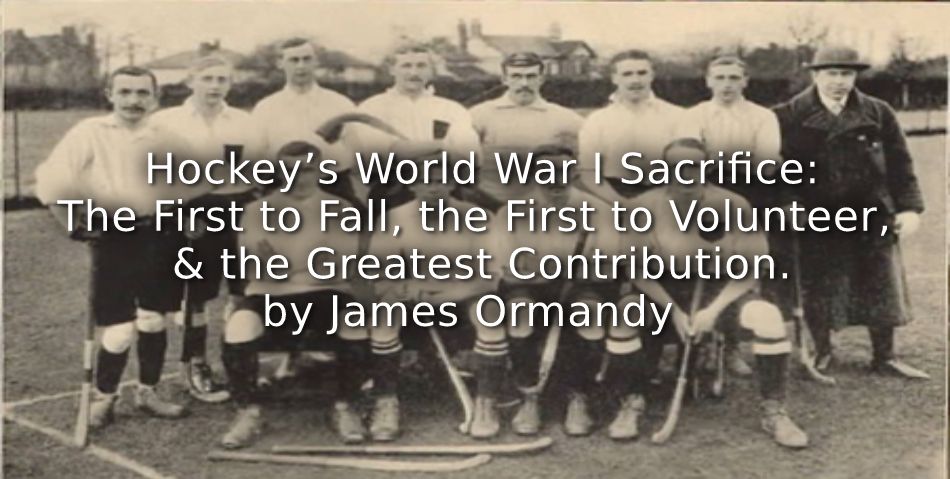

The part that hockey has played in the war will surely enrich the pages of the game’s history when it comes to be written…Many well-known players have secured commissions: in fact, proportionate to exact numbers, no sport has responded more splendidly to the call for men than has hockey. It has been a truly inspiring spectacle and proven the loyalty of hockey men in time of national peril.

And alas the obituary list unfortunately is beginning to grow. Already, several well-known players have given their lives in the noble course of liberty and freedom against the oppression of savage militarism.

Illustrated Sporting & Dramatic News 23rd January 1915

Wars and athleticism have always been historically entwined and from the outbreak of the First World War athletes from various sports were keen to serve King and country. The 1st Sportsman’s Battalion was formed at the Hotel Cecil on The Strand in September 1914 and included some well-known sporting personalities among its number. These included several county cricketers, golfers, athletes, boxers, travellers, and adventurers. Hockey players were just as keen to sign up as any other sportsman. Historians have published volumes covering the contribution made and the demise of famous and international cricketers, rugby players and footballer’s in WWI but to date only Stephen Walker’s Ireland’s Call has made detail reference to the contribution of seven Irish international hockey players to the war effort who lost their lives whilst highlighting the President of the Ulster branch of the Irish Hockey Union’s claim that no other sport in Ulster had made such a large response and follows in detail the career of an international player the Revd. Robert Cecil Morrison’s highlighting his unconventional journey to the trenches with the Cheshire Regiment.[i] Morrison lasted a month at the front, dying when his unit were caught lost in a fog in no man’s land in 1916.

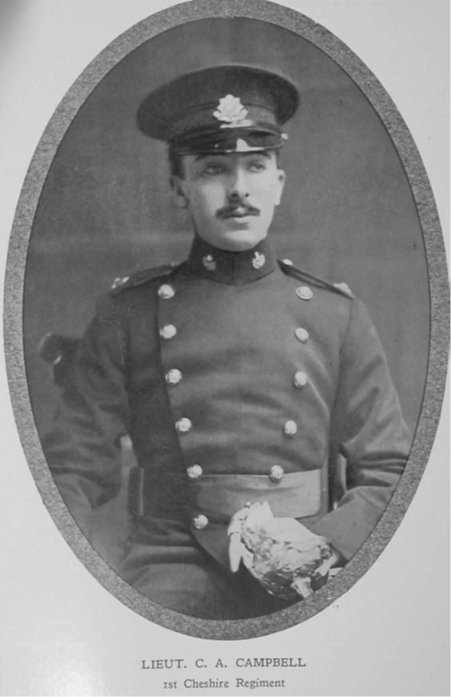

The Cheshire Regiment had been at the front from the beginning of the war as part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) taking part in the first battle of the war at Mons as the BEF attempted to stop the advancing German army. At around 5pm on the 24thAugust 1914 Lt. Charles Arthur Campbell, the captain of the Cheshire Regiment hockey team, at the age of 23 would be the first known hockey player to die, shot in battle. Campbell was 2nd in command, under Captain Ernest Rae-Jones, of “D” Company and the two Officers died together within a few yards of each other either side of the Audregnies to Elouges road close to a small bridge over the railway line where they were sent to find out what had happened to Captain Shore’s patrol. Who was the first Cheshire Regiment officer to die is a meaningless moot point on this day as the “Cheshires” were to be left alone to take on the might of the German army as regiments either side of them withdrew under orders which they failed to receive. Surrounded and fighting a valiant rear-guard action in the open alone against three German regiments of some twelve battalions from 2.30pm onwards they had kept the advance at bay for nearly four hours until they were overwhelmed by just sheer numbers and a lack of ammunition.

David Rowlands’ painting of the 1st Battalion Cheshire Regiment fighting at The Battle of Mons

Lt Charles Arthur Campbell was born in London but grew up in Worthing, he learnt his hockey at Downside School (1901-9) and the Royal Military College Sandhurst before joining the army in 1911 as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 1st Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment. In the 1913-14 season the 1st Battalion were stationed in Londonderry in Ireland. The Cheshire Regiment, under his captaincy were to take on all comers in that season winning the City of Derry Cup and the Ulster Northwest League Cup remaining unbeaten all season.

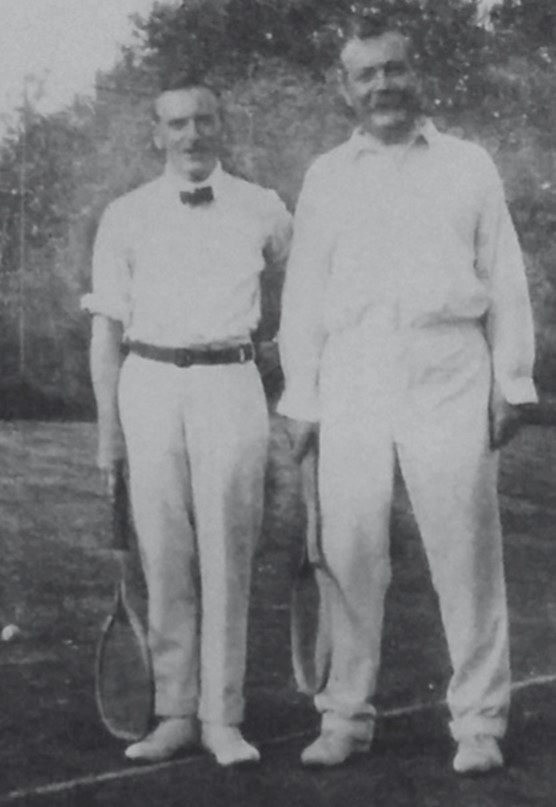

Lt. C.A. Campbell & Lt. T.L. Frost in uniform.

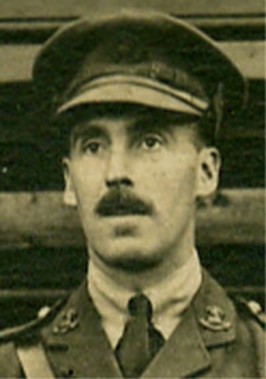

Just a few weeks later, they departed for France where the strength of the 1st Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment marching out on the 24th at Mons was 27 Officers, 1 Warrant Officer and 933 men. At roll call in Bivouac at Les Bavay there were just 6 Officers, a Warrant Officer and 199 men. In just one day seventy-eight per cent of the regiment were killed, wounded or missing with many taken prisoner; 3 officers and 54 NCOs were pronounced dead on the day, 15 officers were wounded as were many other ranks some of whom would die of their wounds days later.[ii] Only forty men were not wounded. Some 490 soldiers were captured including half of the hockey team as the battalion nearly collapsed.[iii] One of those six officers left standing was Chester HC player Lt. Thomas Laurence Frost serving alongside Campbell in D company as the regiment’s transport officer. By March 1915, the promoted Captain Frost was the last surviving officer of the 1st Battalion who had been serving since the first day of the war at Mons for the BEF when he was shot dead in the head by a sniper whilst in the front-line trench preparing for the 2nd Battle of Ypres.

1st Battalion Cheshire Regiment Hockey Team 1913

The devasting loss on its first encounter with the Germans meant that there was considerable infilling over the next few weeks of the battalion with officers from the reserve corps of officers and the Cheshire regiment’s reserve battalion including Oxton HC and England international Capt. Stanley Butterworth who had joined the reserves in 1908. Cheshire’s second top goal scorer with 27 goals in 21 games, Stanley made 13 appearances for the North and two for England against Ireland and Scotland in 1911. He arrived on the 24th September when the battalion was occupied digging defensive trenches at the BEF’s headquarters before returning to the firing line at Festubert on the night of the 12th October. During the night a German patrol would capture Butterworth wounding a NCO and five others.[iv] After his one-night stand Butterworth would spend the rest of the war as a prisoner of war at the former Kurhotel Augustabad (health resort /spa hotel) in Neubrandenburg which was converted to a prison for officers and later at Stralsund POW camp whilst the regiment would suffer more heavy losses with five officers and 55 men killed or missing in action the next day in a failed attack on German lines.

Though hockey had stopped for the war and clubs disbanded, the HA, despite having many of its committee members on active service, continued to hold its AGMs. In the July 1915 AGM it recognised Lt. A. F. H. Round, 2nd Battalion Essex Regiment who played for Essex dying on the 5thSeptember 1914 from wounds he received on the 1stSeptember as the first hockey player to give up his life for King and country. Though, Lt. Round was certainly not the first hockey player to die in WW1 it is hardly surprising that the HA got it wrong as news from the front often came months after the event. Unfortunately, the HA would soon receive news that their current honorary secretary Tony Lovell and his predecessor Philip Collins had lost their lives.

During the first battle at Mons the BEF were being overwhelmed by the German army and were struggling to defend their ground. The Northumberland Fusiliers and the Royal Scots Fusiliers were retreating to the mining village of Frameries pursued by the 24th Brandenburg Regiment. On the morning of the 24thAugust under a heavy bombardment Captain Malcolm Leckie DSO Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) was severely injured by shrapnel whilst attending the wounded of D company of the Northumberland Fusiliers. He remained behind at Frameries as the BEF retreated further being taken prisoner by the advancing Germans only to die from his wounds on the evening of the 28th /29th August in a nearby convent hospital. He was the first of the 903 medical officers who died during the war and the first hockey international player to die. Though wounded on the 24th and dying as a POW a few days later, back home he was reported as wounded and missing in action on 26th September and it was only in December that he was reported as dying from his wounds.

Malcolm Leckie was the son of wealthy businessman James Blythe Leckie and the brother-in-law of novelist Sir Arthur Conan Doyle who later claimed that he was in spiritual contact with his close friend Malcolm after his death. Malcolm studied medicine at Guys Hospital where he was captain of the hockey club; he also played for Blackheath HC, Kent and for England against France in 1907 in the first international between the two countries when England won 14-0. He joined the RAMC in February 1908 after graduating and played hockey for the Army. Captain Leckie, at the age of 34, was certainly the first of fourteen England hockey internationals to die in WW1.[v]

Malcolm Leckie & Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

(Portsmouth Museum Sir Arthur Conan Doyle Collection)

England International Players Roll of Honour

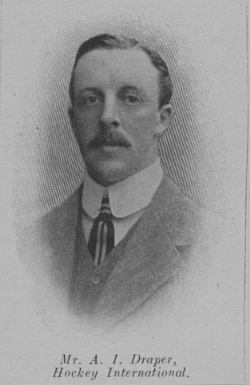

The first battle of the war highlighted the difficulties that the British army would face. The high death rate amongst the regular army necessitated the need to recruit volunteer battalions quickly, it meant fast promotions in the field for athletic well educated young men highlighting the lack of military experience that often handicapped its ability to compete and the need to hold up the Germans so that battles could take place not on open ground but from fortified defensive positions in trenches. Men from the City of London were called upon to volunteer for the 10th Service Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers nicknamed “the Stockbroker’s Battalion” and just five days after Campbell’s death Lord Derby (Edward Stanley) was in St Anne Street Liverpool and the next day at St. George’s Hall addressing volunteers to form a new battalion for The Liverpool King’s Regiment saying: “This should be a battalion of pals, a battalion in which friends from the same office will fight shoulder to shoulder for the honour of Britain and the credit of Liverpool.” Two battalions were immediately formed mainly with men from the business houses with a further two within days forming the 17th, 18th, 19th, and 20th Battalions of the King’s Liverpool Regiment and collectively these would be known as the ‘Liverpool Pals’. Amongst that crowd were four England hockey players Arnold Inman Draper (Bebington HC), Sydney Bertram Heyes (West Derby HC) Charles William Marshall (Oxton HC) and Dudley Holme Scott (Oxton HC) as well as Liverpool born solicitor Reginald Ernest Melly Yorkshire and North (Sandal HC) who were amongst the first volunteers to join the 17th City Battalion, the first of Britain’s Pals battalions, whose war time experiences are worth noting.

Cheshire 1907

Back row: F.S. Church (Bowdon), M. Ravenscroft, W. Wright, S. Butterworth (Oxton), S.B. Chappell (Timperley), G. Hardy (Brooklands), S.W. Menzies (Timperley) G.H. Lings (Hon. Sec.)

Front row: F. B. Peel (Bebington) F.F. Blatherwick, Captain, (Chester), A. I. Draper (Bebington), C. W. Marshall (Oxton).

Charlie’s Five Years of Service for King & Country

Charles William Marshall (1882-1928) was the son of an accountant and music teacher who was educated at Birkenhead Institute from 1891-98 by which time he had made his debut for Birkenhead Park Cricket Club’s second XI and would enter the 1st XI in 1901 and become a permanent fixture in the team being renowned for his batting and fielding. He played hockey at Oxton HC, played 21 times for Cheshire, 8 times for the North and six times for England. He made his Cheshire debut in 1905 in a 7-3 win over Lincolnshire and his England debut in 1907 in a 6-0 win against Wales. A week later he played in England’s first ever game against France which ended in a 14-0 victory and his last international game was in March 1908 against Scotland which ended in a 3-0 win.

Charlie, a marine insurance clerk, joined the 17th Battalion on the 29thAugust 1914 and would return home in October 1919 having spent the last year of service in Russia supporting the ‘White Army’ against the Bolsheviks by which time 753 members of the 17th Battalion would have lost their lives during war. More than twenty per cent of the Liverpool Pals would lose their lives and an estimated seventy-five per cent would be casualties. Few survived without been physically or mentally scared by war and very few front-line officers such as Charlie survived the duration of the war. The 17th Battalion were a well-educated group of soldiers who became a highly successful unit and only such units were put into action again and again as they could be relied upon.[vi]

The 17th Battalion arrived in France in November 1915 and in 1916 they fought at the Somme, the battles of Albert, Transloy Ridge. In 1917 they were on the Hindenburg Line, both battles of the Scarpe, Pilkem Ridge then in 1918 the battle of St. Quentin, the Somme Crossings, the battle of Rosieres, both battles at Kemmel Ridge and the battle of Scherpenberg due to fatalities they were reduced to a cadre before going to off to Russia with the 236th Brigade. Charlie enlisted as a private, quickly became a sergeant and was eventually commissioned and by the beginning of 1918 he had become a captain when he was awarded the Military Cross for distinguished service.[vii] Lucky to survive, on his return Charlie would captain both Birkenhead Park CC and Oxton HC in his first full season back playing in 1920-21. He became the first president of Cheshire Hockey Association in 1922. Unfortunately, Charlie would suffer a fatal fall whilst climbing alone upon Helsby Hill in March 1928 leaving his widowed mother Alicia an estate of £3,434. Charlie, at this time, was president of Oxton HC.

Dudley Holme Scott (1877-1916)

Dudley’s Death at the Somme

Dudley Holme Scott was amongst the 19,240 and the 1,000 officers who lost their lives on the first day of the Battle of the Somme 1st July 1916. Certain regiments suffered more than others which was a fact throughout the war. On that day, the Yorkshire regiments suffered 9,000 men killed, wounded, and missing more than another region in the UK. The 10th West Yorkshire (Prince of Wales’ Own) had the highest death rate at the Somme losing 22 officers and 688 men. The Cheshires only had two companies of the 5th Battalion involved on the first day, company A lost all of its officers and 130 men whilst company B lost three officers including 2nd Lt Philip B. Bass of the ISIS HC and 43 men with 159 wounded including five officers following behind company A trying to cross 800 yards of no-man’s land.[viii] The organisation of the British army was based on regional area commands and locally recruited regiments. Their local concentration was increased by the introduction of Pals regiments consequently when they were at the front suffering losses in major engagements the impact upon local post war economic recovery and sports participation was to be significant. The Accrington Pal’s started the day with 720 men but within the first twenty minutes 235 were killed and 350 wounded or missing in action. During the war more than 850 Accrington Pals lost their lives which would have a major impact on the town and surrounding district.

Dudley Scott, son of a coal merchant, was a cotton broker at the Liverpool Cotton Exchange. He attended Birkenhead School where he described as a useful bat in the cricket XI. He played cricket and hockey at Oxton and was a member of the Royal Liverpool Golf Club at Hoylake. He played for Cheshire and the North playing his one and only England game away to Ireland at Leinster Cricket Club in 1904. Dudley at centre forward would score but England would suffer their first ever defeat losing 3-2.

On joining the 17th Battalion on the first day of enlistment as Private 15187 he was immediately commissioned and appointed commander of A company despite having no military experience. The 17th Battalion would embark for France after a considerable period of training in November 1915 without him as he stayed behind to give evidence into the inquest of Lt/QM Charles Ryder who had committed suicide at the training camp. By the time Dudley arrived the 17th Battalion had acquired the services of another hockey player Captain Stanley C. S. Horser (Oxford University and Oxfordshire) who would fall at the Battle of Transloy Ridge. The 17th Battalion were involved in minor actions losing some twenty men by February but their first major engagement with the enemy would be at the Battle of the Somme on the 1stJuly 1916 when they were at the front line again. At zero hour 7.30 the shelling stopped, and the 17th Battalion were up and out of their trenches to capture their objective the so-called Dublin Trench. According to the 17th Battalion’s diary they faced

“very light infantry resistance but a little machine gun fire encountered; the work of the artillery had been very effective on the German trenches; the objective was seized at 8.30 and company A & B went on a further 100 yards and dug in with the Germans shelling intermittently all morning. Casualties up to 12 noon were company commanders Capt. E. C. Torrey C company and Lt D.H. Scott A company as well as 2nd Lt. P.L. Wright and 100 other ranks all wounded.”[ix]

Dudley would die from his wounds the following day and become one of the 96 Birkenhead School former pupils to give up their lives in the cause.[x] Meanwhile Capt. Cecil Eric Torrey would recover from a gunshot wound to the thigh and be found fighting alongside another England hockey player Arnold Draper only to be shot in thigh again. Dudley was the first Oxton HC player to lose his life, however, he would be soon followed by Captain Guy Ravenscroft, Commander of No.3 company of the 18th Battalion who made his debut for Cheshire in 1914 but lost his life during the Battalion’s attack at Flers on the 17th October.

Arnold Inman Draper: From Private to Major

Arnold Inman Draper was the son of leather merchant Hugh Draper and his mother Gertrude Isabella was a member of the Inman Line Shipping family who died a few days after giving birth to Arnold. Arnold and his father lived with his grandfather Charles Inman who worked with his brother shipping magnate William. The Inman line transported more emigrants to the USA than any other line by concentrating on the bottom end of the market offering cheap fares. Arnold had attended Locker’s Park Preparatory School and he went from there to join his brother Leonard at his father’s old school Rossall in 1894 where he was introduced to hockey. Arnold left in 1899 shortly before his elder brother died of rheumatic pleurisy at the school to join the Bank of England’s Liverpool branch and returned home to play for Bebington HC.[xi] He was also a regular player for the Old Rossallians on their Easter Tours and annual fixtures at Cambridge University.

Arnold played 25 times for Cheshire from 1901 until 1912, 16 times for the North from 1903 until 1911 and made his England debut in 1904 playing against Scotland alongside fellow Bebington teammate Bryan Peel. Unfortunately, his first two international games are remembered for the first time England had not won (England 2 Scotland 2) and for the first time they ever lost (Ireland 3 England 2). However, he did play in England’s first ever international against France in 1907 winning 14-0 scoring twice. Arnold played five times for England and was first reserve on numerous occasions between 1904 and 1908. He was a fast, skilful, and prolific goal scorer whose performance would often determine the outcome of any game as in 1909 when the press reported “Draper beats Brooklands” as he scored all five goals for Bebington in their 5-4 win. Summing up his hockey career is a report from the North v West game in 1908:

“The North forwards played grandly throughout and Draper at inside right was in his best form. Time after time his clever stick work and dribbling powers enabled him to go through the opposing defence and though individually brilliant, he was never selfish.”

He scored the only goal in the game and came close to getting a second hitting the post proving himself to be one of the best forwards in England. He was also a member of the first English side to tour Germany and so popular did he become with Teutonic hockey lovers that he was made an honorary life member of the Uhlenhorster HC Hamburg (1901) who represented Germany in the 1908 Olympics.[xii]

Arnold joined Lord Derby’s first ‘Pals’ battalion as a private, he obtained a commission in March 1915 and due to military professionalism, leadership and the high death rate amongst the 17th Battalion, who saw significant action, he rose to the rank of major in 1917 becoming second in command of the 17th Battalion. Evidence of his bravery and leadership skills appear in the war diaries of the 17th Battalion:

On the night of 4th July 1917 at 12.30am Lt. Aidan Chavasse and a party of 8 other ranks left our trenches to patrol the German front line with the object of ascertaining the disposition of the enemy, obtaining identification, and killing any occupants. This patrol on nearing the enemy wire encountered a German patrol which opened fire on them wounding Lt. Chavasse. Our patrol withdrew to our lines, but Lt. Chavasse was missing. Capt. A.I. Draper, Capt. C. E. Torrey, Capt. F. B. Chavasse (RMAC), 2nd Lt. C.A. Peters and Lance Corporal H. Dixon (11531) searched ‘No Man’s land’ for him. During the search, Capt. C.E. Torrey was wounded and taken into our trenches. 2nd Lt C.A. Peters and L/Cpl H Dixon discovered Lt. Chavasse in a shell hole; 2nd Lt. Peters was killed when returning to our line for assistance to carry the wounded officer in. L/Cpl Dixon remained to bandage his wounds. After waiting the arrival of necessary assistance L/Cpl returned for stretcher bearers to carry Lt. Chavasse in, but on going back the party were unable to find the officer and had to return on account of dawn breaking.”[xiii]

Lt. Aidan Chavasse was the youngest son of the Bishop of Liverpool and brother of Capt. Noel Chavasse (RMAC) the only man ever to win two Victoria Crosses for his bravery for treating wounded soldiers whilst under fire on the battlefield. The Chavasse family were keen hockey players including their sisters Dorothy and twin sisters May & Marjorie who played for Liverpool Ladies, Lancashire and May for the North. Arnold Draper had led this brave but costly mission on the Hollebeke front line. The following night they searched again for Lt. Chavasse to no avail but brought the body of the 22 years old 2nd Lt. Cyril A. Peters back. Capt. Francis Chavasse made several more attempts to find his brother whose body was never found. The following month his elder brother Noel would die from his wounds. Not long after Draper was promoted to Major and became second in command of the 17th Battalion on the 5thSeptember. On the evening of 21st October, the battalion was being relieved of their front-line duties by the 2nd Battalion of the Bedfordshire regiment when Draper was killed, and three other ranks injured when they came under shell fire during the process of leaving their trenches.

Two days later, it was noted in the battalion diary that an unusually large number of officers and other ranks attended the funeral of Major A.I. Draper at Kemel Cemetery at 2.30pm. Arnold became one of the 297 Old Rossallians to die during the war and the third Bebington HC player after Richard Allan Robinson of the Liverpool Scottish Regiment died at Hooge in June 1915 followed by 2nd Lt. William McKenzie Campbell of 9th Battalion of the Royal Irish Rifles died at the Somme having returned to fight from Argentina.[xiv] Though promotion in the field was commonplace there were probably few soldiers in the war who could claim such a rapid rise through the ranks from private to major and second in command of a battalion. Like his hockey in which he excelled, Draper was to prove himself to be an able soldier in the British Army. The Liverpool Echo summed him up writing “it may be truly said of him that he was a born leader of men.”[xv] Sadly, he left behind a widow Evelyn, whom he had married in 1912, and two children.

Bertie Heyes, Punished to Death

Sidney Bertram (Bertie) Heyes was born in 1873 the second son of colliery agent William Heyes. Bertie was educated at Liverpool College and played for Warbreck HC who were a team of Liverpool College Old Boys who took their name from the road where the college is situated. The club disbanded in 1899 and Bertie joined West Derby HC. He made his debut for Lancashire in 1898 playing 25 times for the county and in 1899 he was chosen to play for England against Wales but injury prevented his appearance but in 1903 he played in England’s first ever fixture against Scotland winning 5-0.[xvi] In 1900 he played left half in the first North side to beat the South after ten years of trying and in the 1902 Boxing Day Cheshire v Lancashire 1-1 game he was described as “the best of a sound defence.”[xvii] He worked at the Liverpool Corn Exchange as a broker. Bertie, 41 years old, enlisted as Private 15990 into the 17th Battalion claiming to be 38 years and 200 days old as those over 40 years were not eligible at the time to enlist. He served in France from November 1915 seeing action as twenty members of the 17th Battalion had lost their lives by February 1916.

The Battalion were brought out of line in mid-March and on the 20thMarch Bertie’s C company were paraded for a surprise kit inspection when eleven men, including Bertie, were found to have lost or mislaid their gas helmets. They were immediately brought before their Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel B. C. Fairfax, who sentenced them all to 1 day, Field Punishment No. 1. This was introduced into the British Army to replace flogging and was commonly known by the rank and file as crucifixion and used more than 60,000 times during the war. It was a humiliating punishment and somewhat sadistic, for the miscreant was to be bound to a wagon wheel or other fixed object for up to 2 hours during the day in such a position that he was clearly visible to his comrades. On this occasion they were tied by the neck, hands, waist and feet to a wheel. They were also compelled to do some heavy demanding manual tasks. In addition to hard labour, they would suffer a loss of pay. Prior to undergoing their punishment, each man was examined by the Battalion Medical Officer Lieutenant T. B. Dakin, who despite having treated Heyes just 24 hours earlier for gastric catarrh declared him “quite able to be tied to a wheel”. The fact that being tied to a wheel was only part of the punishment that was to have a devastating effect on Bertie Heyes. By now Bertie was 42 years old and the oldest of all eleven men, but like the others had to firstly dig a hole for the disposal of rubbish before being made to march at the double around the square for some ten minutes. After then being tied to a wagon wheel, allegedly for only 30 minutes, they were released and again forced to march at the double around the square. The official report says that at about 6.40pm, ten minutes after being untied, Heyes complained of feeling unwell and asked for permission to drop out. The Provost Sergeant stated that he readily agreed to this request and accompanied Heyes to the Medical Inspection Room where he complained of acute pain below his right lung and had difficulty breathing. He allegedly then collapsed and died whilst awaiting further medical attention. A subsequent enquiry, ordered by Lieutenant Colonel Fairfax and presided over by Major G. F. Higgins, found that the probable cause of death was Cardiac Syncope, a heart attack which could not have been foreseen. His death certificate recorded the cause of death as “Died of Sickness”.

Another of those who were punished with Heyes was 15771 Private W. Dunn who in 1970 spoke to Graham Maddocks and is quoted in Graham’s Liverpool Pals book as saying:

“We were all given Field Punishment Number One and as the Colonel passed sentence on us he said : ‘I award you this punishment as an example to the Battalion – I am your father, you are my children….After we had been tied up for the second time, and released, we were once again made to run around the square in double time. It was then that Private Heyes collapsed on the road in front of me, crying ‘I can’t go on, I can’t go on’. I stopped and tried to help him up, and he just died in my arms! Sometime later, when I was on leave, I had to go and tell his mother what had happened to him.”[xviii]

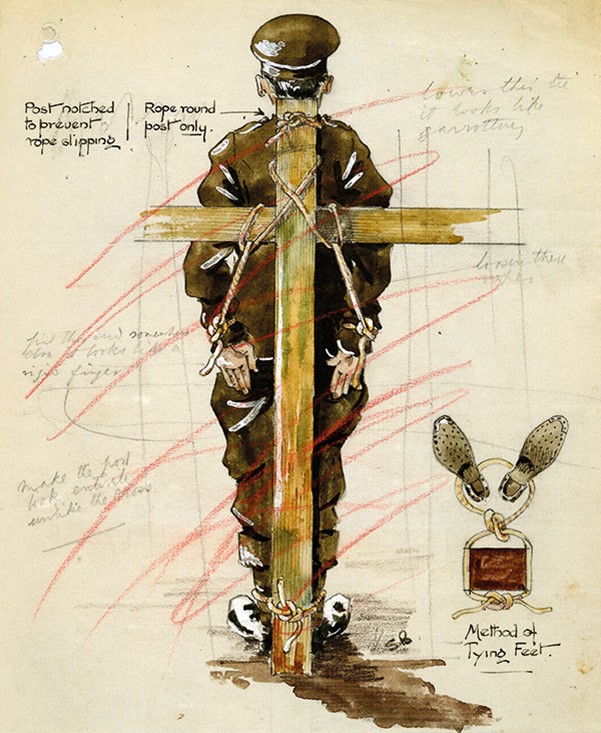

Field Punishment No.1 from a War Office illustration, 1917

The fact that Private Dunn was not required to give evidence at the inquiry, and the discrepancies between his recollection and the statements made by the officers concerned, raises the suspicion of a cover-up. Whatever the truth, there was quite a public outcry. The Illustrated Sunday Herald newspaper’s leading writer Robert Blanchford took a keen interest in the case and in fact others concerning this type of field punishment. For Blatchford the punishment was ‘Boche-like’; a ‘Hun-like torture’ authorised by ‘doltish martinets.’ He stressed that the army currently fighting in France and elsewhere was made up of patriotic volunteers, who had left decent jobs for the good of their country. Moreover, the army was ‘the King’s Service … not a reformatory for the punishment and reclamation of refractory hooligans and thieves.’[xix]

Questions were asked in Parliament with Quaker MP Philip Morrell particularly involved. During a debate in the Commons on 21st December 1916 he brought up the case of Bertie Heyes but did not actually name him. Instead, he referred to an interview with the Evening Standard given by General B E W Childs who was Director of Personnel Service. The transcript of the interview is reproduced here, taken from Graham Maddock’s book “Liverpool Pals”. It is quite a contrast to the version of events recalled, with clarity, some 54 years later by Private Dunne.

“The soldier concerned, together with eleven other men, was sentenced to one day’s field punishment No.1. On the morning upon which he was sentenced, he was medically inspected by the medical officer of the battalion, who certified him as fit to undergo the punishment. The field punishment consisted of fatigue. From 1.45 to 4.40 the men were employed in digging a hole for the disposal of rubbish. From 4.40 until 6 they were doing nothing. They were then confined under the conditions laid down in the Rules for Field Punishment, for half an hour. Here, it should be noted that the maximum period allowed is two hours. Subsequent to this, the soldier concerned, whilst on the march, asked leave of the provost-sergeant to fall out, as he did not feel well. The sergeant himself took the man to the medical inspection room, where he was placed on a stretcher and made as comfortable as possible. He complained of acute pains below the right lung and difficulty in breathing. He shortly afterwards collapsed and died.

A post- mortem examination was held the next day, at which the Lieutenant Colonel, a major, two captains and an expert bacteriologist were present. They investigated every organ of the man’s body, and apart from some slight trace of fatty disease of the heart, there was no other evidence to the naked eye of the cause of death. In the words of the finding of the post-mortem the only suggestion is that of an acute attack of dilation of the heart supervened”.[xx]

Whether there was a cover-up or not a public outcry over Field Punishment No.1 had begun. Field Punishment No 1. was available to courts martial in theatres of operations for offences that ranged from losing equipment to drunkenness and from selling rations or supplies to attempted rape. The significant thing about the punishment, however, was the requirement that the offender be tied up for two hours a day for three consecutive days out of four and for a period totalling up to 21 days. The tying up was designed as a warning to others and a humiliation for the offender and it harkened back to the old shaming punishments of the stocks and the pillory. But, like these, it often had the opposite effect from that intended. In particular, the variants that were developed on how to tie up the offender evoked sympathy and incensed the rank and file. Nevertheless, it would appear to be common practice in the Kings Liverpool Regiment as Lieutenant Colonel S.C. Marriott, who commanded a territorial battalion of professional soldiers wrote home early in 1916 explaining to his father how he was bringing his men up to a new level of discipline:

… the last time we went down for a rest I had as many as 31 men tied to the wheel at the same time. In the old days this would have been heart breaking [in the Territorials] but nowadays it is very different, all sentiment has gone to the winds. Even Eckes, my second in command, had his faithful servant strung up for forgetting to put his anti-gas helmet over his shoulder one day. Eckes did not like it at all but realises the necessity of these things now.[xxi]

Blatchford’s article appears to have crystallised a growing popular disquiet. It encouraged a wave of protest letters and petitions from individuals and organisations. The War Office enquired of French and Italian allies about how they punished in the field. Senior generals were consulted and most insisted that the punishment was necessary. Sir Douglas Haig, for example, thought that removing men from the Western Front to prison would provide a wrong signal and allow men to shirk their dangerous duties. He reiterated the belief that the stigma provided by the punishment was good both for the offender and as a deterrent to others. Moreover, he feared that abolition would have disastrous consequences and would mean that:

… a far larger percentage of those men whose moral fibre requires bracing by the daily fear of adequate punishment would give way at moments of supreme stress, and that recourse to the death penalty would have to become more frequent.[xxii]

The outrage expressed across the country was such that the army council thought it necessary to draw up precise details of how the punishment was to be carried out in future and particularly without the brutal extras that had come to characterise it. A watercolour sketch was prepared of what Field Punishment No 1 should look like. The scarcely visible pencilled comments noted on the sketch emphasise the sensibility felt at the highest military levels, who seem to have been more aware and more considerate of popular opinion than Haig. The ropes were not to look too tight. The rope at the top of the post was to be lowered otherwise ‘it looks like garrotting’. Perhaps most significantly: ‘Make the post look entirely unlike the Cross.’ Other sketches followed and in January 1917 a printed form was issued with an illustration on one side and detailed instructions on the other of how the punishment should henceforth be carried out. The instructions stated specifically that a man’s feet were not to be tied more than 12 inches apart and that he must be able to move them three inches; more significantly, if a man’s arms and wrists were tied, there was to be at least six inches’ play between them, and the fixed object and they were to be tied either at a man’s side or behind him. A subsequent instruction declared that Field Punishment No 1 should only be awarded for offences of ‘a disgraceful or insubordinate nature or for drunkenness’.[xxiii]

Bertie’s loss of his gas mask whilst leaving the front line and crossing marshland under fire and his subsequent death under Field Punishment No.1 led to the reform of the policy though it would take until 1923 for Field Punishment No. 1 to be abolished. Lieutenant Colonial Fairfax was ironically to suffer the effects of exposure to gas, and it is not known whether he had his gas mask with him! He was evacuated to England where he survived the war never returning to the Pals. Major Higgins who presided over the Inquiry was himself killed in action on the 30thJuly 1916 now remembered as Liverpool’s blackest day when just less than 2,000 Liverpool Pals went over the top at Guillemont on the Somme only for 1,115 of them to be killed, missing, or captured with almost 500 confirmed dead on the day. Among the dead were the Lt Reginald E Melly now with the 20th Battalion and ‘Styx’ the Birkenhead News hockey columnist Capt. Walter Willmer of the 19th Battalion who had done much to promote the game on the Wirral whilst playing for Oxton HC. His brother Wrayford, a lieutenant in the 17th Battalion, and his cousin Capt. A. Franklin Willmer of the 9th Rifle Brigade were wounded in the battle and Franklin would die from his wounds in September. The Willmer family were newspaper proprietors and printers and whose sons, like our internationals, were public school educated athletic young men who had volunteered and found themselves, despite having no military experience and for many limited training, leading men into battle to face virtual certain death or injury. From the assumption that the amateur hockey player would of course always be a gentleman it was a short step, readily taken, to the assumption that he could be an officer in Kitchener’s army. The British army commanders’ belief that a public school sporting life gave these young men the leadership qualities along with the moral and physical wherewithal to excel on the battlefield was born out of necessity as part of the regular army had been lost at Mons so had to be hastily replaced by those with a sense of duty and chivalry, born out the public school ethos, allied to the cult of athleticism therefore could be relied upon to lead. The assumption had a firm foundation as most public schools served to some extent as military academies and a few such as Wellington, Cheltenham and Clifton had military rather than university aims.[xxiv] Unfortunately, the opportunity for the Christian ideal of a ‘good or honourable death’ or for honour and glory which was part of this ethos would be lost by the likelihood of a death either crossing no-man’s land or the ‘shell with your name on it’. The notion of the sport of war and the sporting chance had been lost to the new technologies of modern warfare so that the Boer War would be remembered as the last gentlemanly war. As for Bertie, at his age of 42, he had no obligation to enlist and it seems so unfair that such a man, a patriotic volunteer, should ignobly die so unnecessarily punished to death though the punishment policy amendments that followed his death may have saved the lives of others.

The experiences of these Liverpool Pals of the 17th Battalion summed up the brutality of the major offensives, front-line trenches could be a terribly hostile place to live. Units, often wet, cold, and exposed to the enemy would quickly lose their morale if they spent too much time in the trenches. As a result, the British army rotated men in and out continuously. Between battles, a unit spent perhaps 10 days a month in the trench system and, of those, rarely more than three days right up on the front line. It was not unusual to be out of the line for a month playing football, hockey, and other sports to occupy the down time, so it was often a matter of luck when, where or if your battalion was deployed on the front line of a major offensive. The lucky volunteers and later the conscripted returned to a society scarred by their experiences. The junior officer class of which there were numerous hockey players suffered the most. The public schoolboys may have only counted for 1% of age group but they accounted for nearly two thirds of the officers who served in the war, their patriotic games ethos had been mimicked in the old and new grammar schools and from 1902 the new secondary schools, their sense of duty led them to be amongst the first to volunteer but it was their ethos that permeated throughout Edwardian society that predisposed so many others to volunteer to fight. Hockey had been a game for the upper classes and the upper middle classes in the 1890s most of whom were varsity men and public school educated and by the Edwardian era the game spread across the strata of the middle class whose offspring had taken up the game’s ethos at grammar or the new secondary schools. By July 1915 the HA claimed that of the 4988 players in England’s affiliated clubs at least 2707 had enlisted in the army or navy. However, given that the number of unaffiliated clubs outnumbered the affiliated by a factor of three or more in many areas the number of hockey players serving in the forces was considerably more.[xxv]

The international players who lost their lives were just the tip of the iceberg. Ireland lost eight international players, but one Dublin club Three Rock Rovers had 164 past and present players serving in the British forces and of these twenty-four made the supreme sacrifice.[xxvi] The Oxford club ISIS had 160 past and present players serving in the forces losing eighteen players by July 1916 but by November the figure had risen to thirty-four players with more than half of the cohort appearing wounded on casualty lists.[xxvii] Lisnagarvey had thirty-eight players enlist with six making the ultimate sacrifice. The Ulster Clubs Roll of Honour amounted to Banbridge 9, North Down 9, Holywood 7, Lisnagarvey 6, Cliftonville 6, East Antrim 6, North of Ireland 5, Osborne 5, Ards 3, Queen’s Univ. 3, Antrim 2, South Antrim 2 and Lisburn 1.[xxviii] These figures were replicated across the U.K. Hockey’s casualty lists and rolls of honour would handicap the game’s post war recovery. It would take nearly ten years for the membership of the northern counties hockey associations to reach pre-war levels. Hull had as many as nineteen clubs in its district in the Edwardian era yet only five reappeared post-war and two would merge soon after reducing the figure to four. Warrington’s two premier clubs Latchford HC and Stockton Heath HC would merge purely due to the number of casualties of club officers and players suffered which made recovery difficult. Manchester’s Kersal HC, one of the first clubs in the north was among many that never reappeared.

Ireland International’s Roll of Honour[xxix]

References

[i] S. Walker Ireland’s Call. Irish Sporting Heroes who fell in the Great War (Kildare Merrion Press 2015) p184-203

[ii] 1st Battalion Cheshire Regiment War Diary (transcript G.E. Conway 2008)

[iii] A. Hine Refilling Haig’s Army: The Replacement of British Infantry Casualties on the Western Front 1916-18 (Warwick Helion & Co 2018) p43

[iv] Col. A. Crookenden The History of the Cheshire Regiment in the Great War (Eastbourne A. Rowe Ltd. 1938) p26

[v] https://kingscollections.org/warmemorials/guys-hospital/memorials/leckie-malcolm (Accessed 20/02/2022)

[vi] G. Maddocks Liverpool Pals. 17th 18th 19th 20th Service Battalions. Liverpool King’s Regiment 1914-1919. (Barnsley Pen & Sword Books Ltd 1991) p216

[vii] 17th Battalion King’s Liverpool Regiment War Diary January 1918. WO-95-2334-1_2.

[viii] Col. A. Crookenden p67

[ix] 17th Battalion King’s Liverpool Regiment War Diary July 1916. WO-95-2334-1_2.

[x] A Seldon, D Walsh Public Schools and the Great War: The Generation Lost (Barnsley Pen & Sword Books 2013) p254

[xi] L.R. Furneaux, The Rossall School Register 1844-1923 (Rossall, 6th Edition)

[xii] Illustrated Sporting & Dramatic News 27th February 1909

[xiii] 17th Battalion King’s Liverpool Regiment War Diary July 1917. WO-95-2334-1_2.

[xiv] Birkenhead News 10th September 1915, Liverpool Echo 7th July 1916, The Wirral Cup 2015 Souvenir Programme Remembering our Hockey Forefathers. (Chester Hockey Club 2015)

[xv] Liverpool Echo 31st October 1917

[xvi] West Derby (Liverpool) Hockey Club 70th Anniversary: A Short History 1887/8 to 1957/8 p11

[xvii] B. Thornber & W. Thornber Twenty-Five Years Hockey Memories (Cheshire, Cheshire HA 1913) p155

[xviii] G. Maddocks p75

[xix] C. Emsley, Humiliating, painful & reminiscent of crucifixion the British army’s Field Punishment No.1 fuelled public anger during the First World War. History Today Vol. 62 Issue 11 November 2012

[xx] G. Maddocks p76

[xxi] C. Emsley 2012

[xxii] Ibid

[xxiii] Ibid

[xxiv] W. J. Reader, At Duty’s Call. A Study in Obsolete Patriotism (Manchester MUP 1988) p90

[xxv] Western Mail 9th July 1915

[xxvi] T.C.S. Dagg Hockey in Ireland (Tralee Kerryman Ltd 1944) p62

[xxvii] Oxford Chronicle 10th November 1916

[xxviii] Northern Whig-Belfast 11th April 1919

[xxix] John George Anderson Banbridge HC is often claimed to be an Irish international who lost his life, but he played six times for Scotland and his brother presented the Ulster Hockey Union with the Anderson Cup which is still played for today.

Hello, I’m research the lives of those former pupils from Hereford Cathedral School who fell in WW1. I’ve now got to Captain William Lionel Carver of the Herefordshire Regiment.

School records confirm: He Played Hockey for Herefordshire, 1906-07, and for Leeds Corinthians. Yorkshire and North of England, 1907 – 09. Afterwards was with Messrs. Baker and Lillington, Weston-Super-Mare, and was Captain of Weston-Super-Mare Hockey 1st XI., often appearing for Somerset and the West of England, and also Captain of Weston-Super-Mare Cricket XI.

Was Captain of the English Hockey Team which visited Hamburg, 1912-13.

( Your website confirms Hockey was not included in the 1912 Stockholm Olympics. So as not to miss out completely, Germany decided to host an alternative tournament in Hamburg. They invited six other countries to join them but only England and Austria accepted and attended. We believe that England won both of their games though the results do not appear in the England records. Indeed, the only recorded results of this tournament are those kept by the Germans. 13/10/1912 Germany 3-8 England).

Is there an official English Hockey WW1 roll of honour like the Wisden did for Cricket?

Thanks for any information

Tours

George Clegg