Some interesting sport journalism finds in the digital archive of the forgotten US periodical

First published in 1926, The Chicagoan was the Windy City’s answer to The New Yorker, modelled closely on its style and content. However, The Chicagoan never found the readership and reach of The New Yorker, ceasing publication during the Great Depression in 1935.

Decades later, cultural historian Neil Harris discovered the archived collection of The Chicagoan in the library of the University of Chicago. The find inspired him to spend twenty years researching the magazine’s history, culminating with the book The Chicagoan: A Lost Magazine of the Jazz Age in 2008.

The University’s collection is now digitised and available for use online. I didn’t expect the search term “rugby” to return much, but it did, interestingly, provide a few articles of note. Excerpts of these articles are published below.

18 January 1930

Editorially

This is, among other things, the Athletic Age in American civilisation. The great growth of public interest in games of skill and strength during the past ten years may be noted as a favourable trait in the national character. It offsets certain symptoms of decadence that are plainly visible — our feverish obsession with the subject of sex, for example.

The athleticism of the era will be expressed in the program of the World’s Fair of 1933. A committee of leaders in the realm of sports has been appointed to supplement the exposition with an impressive pageant of competitions in all branches of athletic prowess.

Football, as the most popular of amateur sports, will receive special emphasis. Therefore we wish to toss the committee a suggestion. Let there be placed upon the calendar for 1933 an exhibition to be held on Soldier Field under the title of ‘The History of Football’. It should be a contest between two squads of All-Americans which will illustrate the evolution of the game.

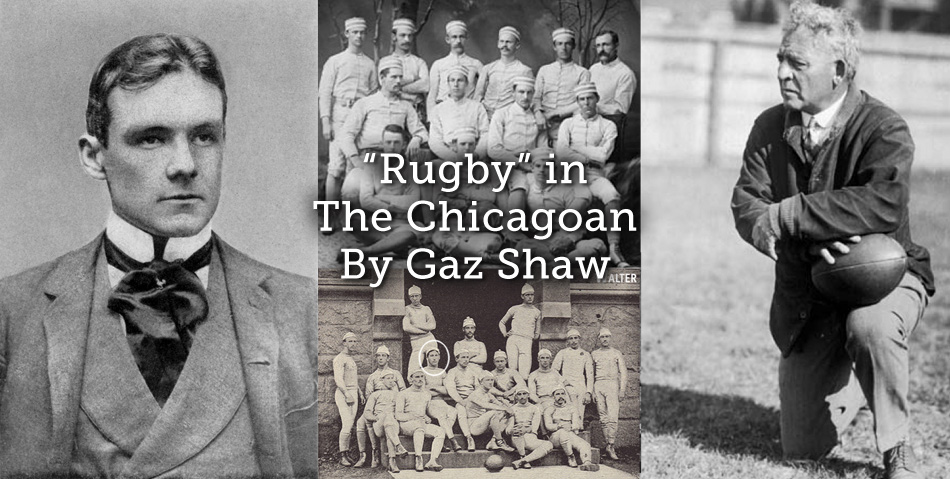

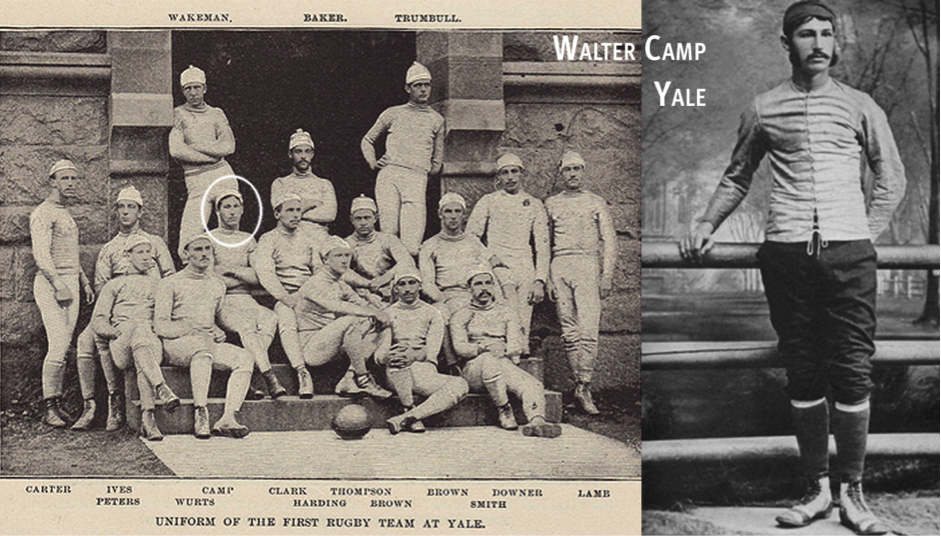

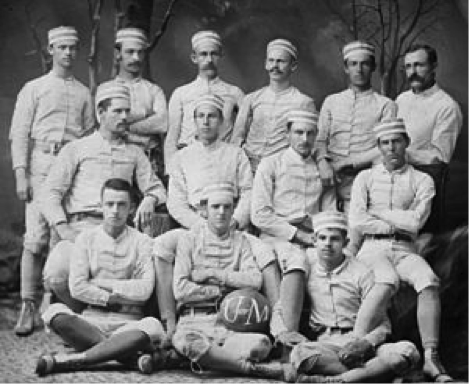

The first quarter should be Rugby—the British game out of which American intercollegiate football sprang. The second quarter should be football in the style that prevailed when Walter Camp was a star at Yale. The third quarter should be played according to the mass-and-power technique of the ‘five yards in three downs’ period, with 1900 as a convenient date for the rule-book. The fourth quarter, of course, should be the modern forward-passing game. The changes in uniform, as well as the rules, should be followed; and the players should be carefully trained in preparation for the event.

- Walter Camp and the Yale Rugby Team

This is a veritable Tex Rickard of an idea. Such a game would be amusing, picturesque and instructive; and its possibilities for ballyhoo would be unlimited. Amos Alonzo Stagg, please note.

6 December 1930

‘Football’s First Step West’ by Wallace Rice [excerpt]

Prevailing uproar about college football, past, present and to come, had its modest beginnings in the first game played west of the Alleghanies fifty-one years ago last May, when I acted as an umpire. It was between Racine College, since moribund, and the University of Michigan.

- Wallace Rice

Michigan won by a goal and a touchdown, the six safeties Racine was compelled to make not being counted in the score. Nor, for the matter of that, was the touchdown; the score was given as one goal to nothing. And that goal was kicked in the last two minutes of play.

It wasn’t such a bad game, but it would hardly be recognized today as a game at all. Nobody on either side had ever seen a game. Michigan had no coaching by anybody who had ever seen a game. I was home on a forced vacation from a prep school in Massachusetts, where I’d played through the fall of 1878 on an amateur eleven called the Newtons. Both sides were as polite as football players ever were, and there were no disputes worth mentioning.

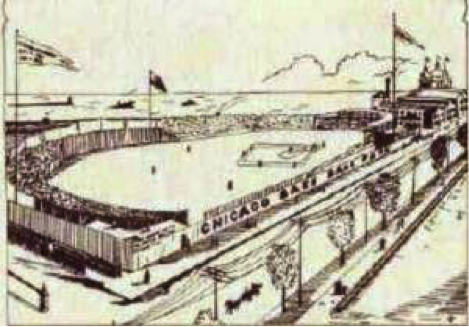

It was Friday, May 30, Decoration Day, and hotter than need be—80℉ in the shade, and we were in the sun. The place was the old White Stocking Ball Park, on the Lake Front just across from where the Public Library now stands. There were side and goal lines marked out, but no yard lines to make a gridiron of the field, there being no penalty for downs in those days. In fact, the game was played chiefly by main strength and awkwardness, and it was customary for the heavier side to get the ball and force their way down the field a foot or an inch at a time until they made a touchdown, holding the ball for half an hour or more at a stretch in the process.

- Lakefront Park

The rules were much closer to English Rugby than they are today, as may be seen by the 0 to 0 game Harvard played with Yale that autumn, with the old fifteen men on a side. The wind was high from the south west. Michigan won the toss and gave Racine the kick-off against it.

In those days, let it be said, they played two forty-five minute halves, with a fifteen minute recess between. The game was called at 3:45, with about 500 spectators in the grandstand.

The teams were as follows:

Racine:

Alexis Du P. Parker (captain);

C. K. G. Billings, L. Rogers, A. C. Torbert, A. L. Cleveland, George W. Roberts rushers;

K. Green, Frederick S. Martin, Sidney G. Ormsby, halfbacks;

J. W. Johnston, A. L. Fulforth, backs.

Michigan:

D. De Tarr (captain);

John Chase, Irving K. Pond, J. A. Green, W. W. Harman, Frank F. Reed, R. G. De Puy, forwards;

R. I. Edwards, C. H. Campbell, E. H. Barmore, halfbacks;

C. S. Mitchell, goalkeeper

It will be noticed that Racine had six and Michigan seven in the rush line on paper, the first being the disposition usual in those days. After the game began one of the Michigan men dropped back. There were no quarterbacks, so designated, but two of the halfbacks played each close to his center-rush, of whom there were two, one taking the balls on one side in the line-up, and the other on the other.

The Michigan men were older and heavier, and they forced the play, keeping the ball near the Racine goal and compelling five safeties in the first and one more in the second half. The touchdown was made about the middle of the first half. Green got the ball for Racine and started down the field. Irving Pond, inches over six feet and weighing more than 200 pounds, caught him by the neck of his jersey, bracing himself, and sending Green, who was a little fellow, into a complete forward somersault. He dropped the ball, De Puy picked it up and ran it over, but Michigan missed the goal.

- Michigan Team

The Racine men thought they had the best of it on condition and wind, but when they lined up for the second half, Pond turned one of those somersaults for which he has since become nationally famous—he’s still turning them at the age of 73—and that was discouraging. But Racine got the ball into Michigan territory and the game was not settled until almost the last minute of play, when John Chase made a fair catch from a Racine punt, and Captain De Tarr made the goal from a place kick near the twenty-yard line.

It was years before the game really got a hold here in Chicago after that little start. Eleven years later, when I was a reporter, I was the only newspaper man in town who had any knowledge of the game whatever, and I reported all the earliest contests—and they were good ones—between the all-star team the Chicago Athletic Club put into the field against the Boston Athletic Club and an occasional eastern college team. And now look at the multitudinous thing.

9 May 1931

‘The Playful Barbarians’ by James Weber Linn [excerpt]

This seems to be a good time to write about intercollegiate athletics, I don’t know why. Nobody except a few of the strong boys is interested, and not many of them can read without breathing hard. Yet on the other hand the conduct of intercollegiate athletics today is beset with problems.

The subject of intercollegiate athletics is historically interesting. In 1860 there were 10,499 college students in the East, 16,959 in the Northwest, and 25,882 in the South.

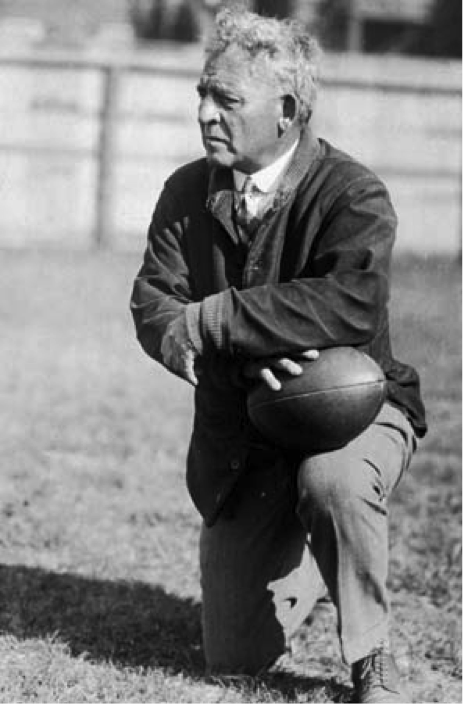

Eighteen Hundred Sixty-two marked the birth of Amos Alonzo Stagg, from which most modern historians date the beginning of intercollegiate athletics, often called ‘character-building’. In 1867 Yale and Harvard began rowing with each other. The Harvard-Princeton row came later. In 1873 was the first performance of The Black Crook, which demonstrated how much more popular legs are than brains, and which was generally called ‘the panic of ‘73’. This led to football, and ultimately to the University of Southern California.

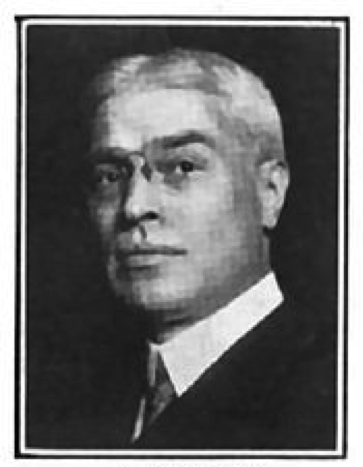

- Amos Alonzo Stagg

There are today more baseball players from the University of Alabama in the big leagues than from any other educational institution. With this as a background we may continue our discussion.

(I forgot to say that set in an ivied brick wall at Rugby, in England, is a tablet which reads, ‘This stone commemorates the exploit of William Webb Ellis, who, with a fine disregard for the rules of football, first took the ball in his arms and ran with it, thus originating the distinctive feature of the Rugby game, A. D. 1823’. The distinctive feature of the present game of football is the use of the word ‘over emphasis’, but I have searched in vain for any record of a monument to the man who first took it in his mouth.)

Intercollegiate athletics is today the cornerstone of American character building. Every boy who competes signs a statement which reads, ‘I hereby certify that I have received no financial assistance, direct or indirect, on account of my participation in athletic competition for Blank College’. On this affidavit he builds up that structure of rectitude and sportsmanship which has been so aptly described as ‘one hundred per cent Americanism’. Over the doorway of this magnificent edifice may be read the words, ‘Equal Opportunities for All’, like a beacon shining afar and lighting the way to advancement.

Literature arising from the study of the game of football, however, generally fails to reach this high level.

It is a game which abounds in thrills—legitimate, inspiring, blood-tingling thrills. A brilliant long run made possible by skillful dodging aided by timely and clever interference—a flying tackle by the last man between the runner and the goal-line—a ‘they-shall-not-pass,’ ‘never-say-die’ defense of a team’s goal—a team coming from behind and snatching victory from defeat in the last minute of play by sheer skill and grit—all these provide thrills a-plenty for the true sportsman.

So writes Dr. E. K. Hall in the 1930 Football Guide. Alas, these ringing words do not provide ‘thrills a-plenty’ for me. They force me rather to inquire philosophically into the difference between a legitimate thrill and an illegitimate thrill; to consider the exact adjectival significance of ‘blood-tingling’; to wonder if brilliant dodging through grammatical constructions is not as important as through clutching adversaries on a football field; to doubt whether skill which is sheer can be at the same time gritty. It must be admitted that ‘sport-writers’, describing actual football games, do rather better than this. But I do not recall any anthologically-preserved passage of ‘great writing’ which had its inspiration in intercollegiate sport.

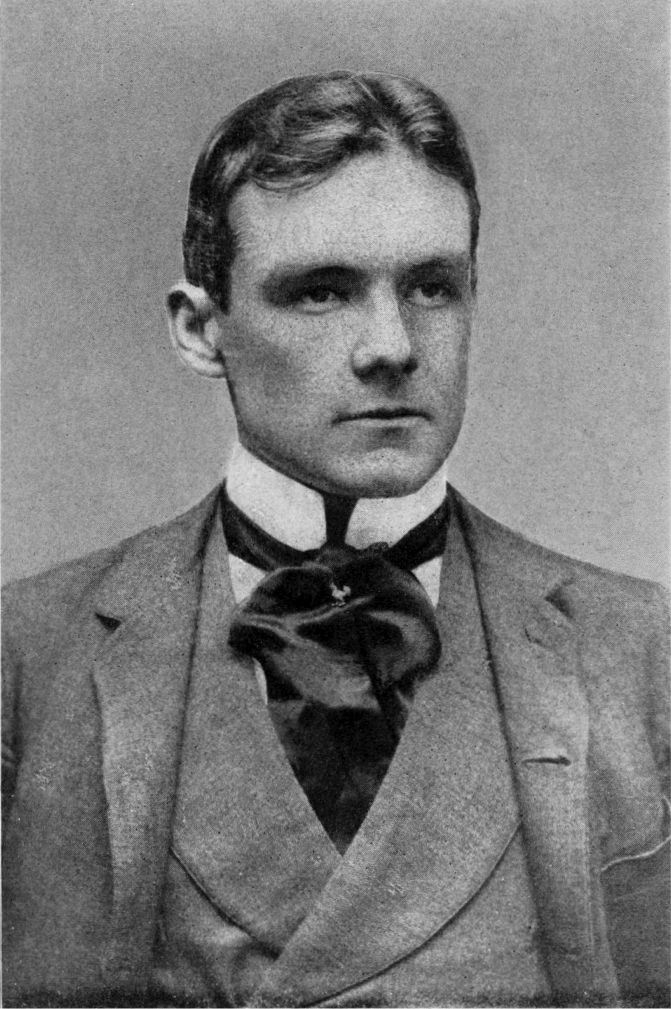

To be sure, there was Richard Harding Davis—but he wrote on sports long ago, before they had assumed their present statistical importance.

- Richard Harding Davies

More than as a ‘character-builder’, however, and far more than as an influence on American culture, intercollegiate athletics is important in education. Many a young collegian has undertaken his first serious study of arithmetic in connection with intercollegiate athletics. One hundred seventy-five pounds times 10 2/5 seconds per 100 yds. equals what, and where? How many touchdowns in four years in high school equal one passing grade in Freshman English at (a) the University of Iowa, (b) Duke University? Five Saturday afternoon victories, divided among how many Evanston businessmen, equal one blue roadster? Two touchdowns after forward passes equal how many mash notes for (a) the passer, (b) the catcher?

Problems such as these are put up to our more earnest students of the game constantly… And let us never forget that these athletes are mere boys. They cannot fairly be held responsible for such errors of judgment. I like to think, as I watch some frail two-hundred pounder playfully dig an elephantine knee into the bowels of a prostrate opponent, or perceive a black jowled basketball guard, prematurely bald from excessive application to the study of the higher calculus, deftly trip a dribbler, that these are just children after all.

It is on account of its educational value that I feel we should take more interest in intercollegiate athletics than we do. The general public should, I mean. Where shall we find leaders of the nation, if not among our intercollegiate athletes? Examine the roster of our All-Americans, for instance. Was not the battle of Waterloo won on the playing-fields of Eton?

1 August 1933

‘Chicagoana’ by Donald Campbell Plant [excerpt]

This summer Chicago has been playing host to numerous inroads of Italians, Moroccans, Japanese, Chinese, Scandinavians, Belgians (there’s still that little money matter, so there haven’t been any French to speak of) and other nationalities. And now, to top off the whole thing, we are to be visited by the Cambridge University Vandals, a private English Rugby club, traditionally sporting and steeped in the air of Piccadilly, Leicester Square and the Mall.

The Vandals are made up of Cambridge and Oxford alumni and include, we understand, several of the finest Rugby players in the world. They will play four games in the Middlewest: August 29, against a picked team of the Illinois Rugby Union at the Oak Park High School Stadium for Infant Welfare charity; a private match against the Goths at Onwentsia on a later date; versus the Rugby Union at Stagg Field on Saturday, September 2, kick-off at 3pm; and against the Cherokee Rugby Club, an American organization similar to their own, for local charity in Benton Harbor.

- Early Cambridge Uniform

Rugby, as most people should know but don’t, is the father of American college football. It is the main college sport of the British Empire and in recent years has become very popular among French and German schools. Scores are made by touchdowns and goal-kicks. There’re passing, tackling, punting, broken-field running and all the other thrills commonly associated with football, but in Rugger—as it is affectionately known among Britishers—there are fifteen men a side. There are no substitutions allowed at any time, play is divided into thirty minute halves and players are not allowed any protecting devices such as helmets or shoulder pads. They wear thin cotton jerseys, shorts and ordinary football boots and stockings. The game is fast, open and continuous like ice hockey. If a man is tackled with the ball, he must loose it immediately and play goes on without stoppage.

Britishers say—and they don’t often boast without cause—that Rugger is among the cleanest, most thrilling and sporting games in the world; that is why at international games a hundred thousand spectators is an ordinary and expected gate. And all Rugger players are amateurs in the strictest sense.

1 September 1933

‘Handicapping the Sports’ by Kenneth D. Fry [excerpt]

A group of gentlemen known as Vandals gave us a polite exhibition of the football game known as Rugby, showing what appeared to be great skill in beating a local outfit. To our simple mind the game appears to be quite complicated and disorderly. However, we are assured that such is not the case. It is a disorganized game when one is accustomed to the regularity and precision of American football, intercollegiate brand. Perhaps that is a trifle unfair since intercollegiate football is a mystery to most people, including most broadcasters. Anyhow it is a trifle disconcerting to find sports scribes muttering in print that Rugby will never replace intercollegiate football. Whoever suggested it would?

Article © Gaz Shaw

The Chicagoan digital archive is available to view online at the University of Chicago Library website. The Chicagoan: A Lost Magazine of the Jazz Age, a book by Professor Neil Harris, was published by University of Chicago Press.