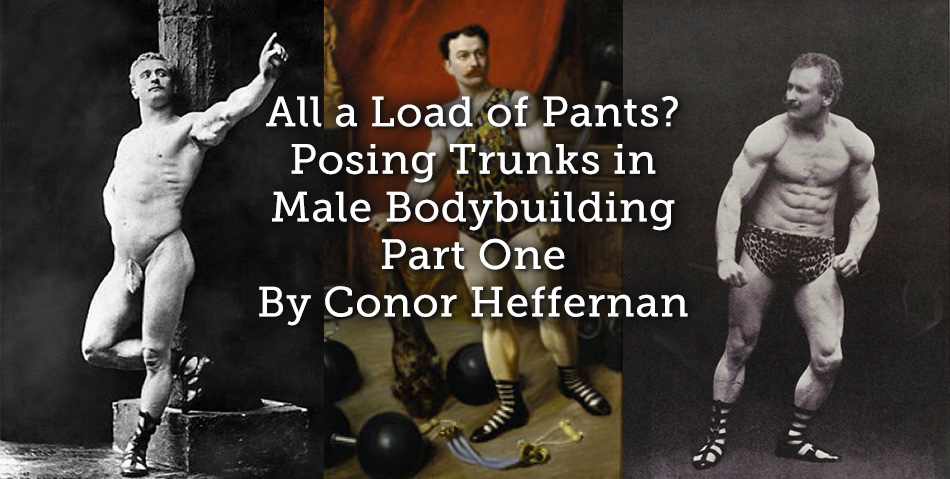

At first glance posing trunks seem an odd subject for historical enquiry. Bodybuilding as a sport is almost entirely devoid of clothing leading one undoubtedly to wonder just what can be gained from studying the miserly cloth that remains. The answer, somewhat surprisingly, is quite a lot.

Following a revived interest in bodily development at the dawn of the nineteenth-century, fitness promoters and competitors have sought new ways to display the superiority of their physiques, messages or training systems. Far from an isolated activity such approaches were informed by the societal messages, boundaries and ideals of their day, a crosscurrent that informs today’s article.

Tracing bodybuilding and its predecessors from the early nineteenth century onward, the following articles looks at bodybuilding through three different lenses: art, commerce and competition. A troika of sorts, which has influenced how much and how little clothing has appeared on the bodybuilding stage.

Bodybuilding as Art

One of the most popular mantras iterated by bodybuilders in the present age is that the pursuit is more akin to art than sport. Whether or not this is a desperate attempt to gain respectability for a sport routinely labelled as freakish, is irrelevant for today’s interest. What is important to note is the historical precedence for such claims.

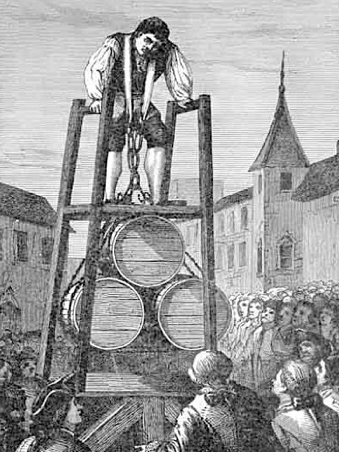

While strongmen have been a mainstay in both British and European history throughout the centuries, such men’s public appearances have tended to be rather modest. One example being Thomas Topham, an eighteenth-century British strongman whose feats of strength was the stuff of legend. Capable of manipulating steel roads, holding back wild horses and even lifting a collection of barrels weighing several hundred pounds, Topham was undoubtedly one of the forerunners of British strongmen. Unlike his successors however, Topham’s public appearances saw the Islington man donned in respectable clothing. No loincloths, trunks or flesh of any kind on show. An observation, which suggests that the male body was still considered a relatively sacrosanct thing.

- Thomas Thopham – Harness Lift 1741

When then, did it become acceptable for strongmen to display their muscles for all to admire?

According to Jan Todd, it was not until the closing decades of the eighteenth century that British culture became more receptive to the male form on display. A cultural turn largely influenced by the influx of Greco-Roman art within the British Isles. Beginning with the Elgin Marbles and continuing right through, the statues became emblems for health, strength and masculinity within England. Such interest in Greco-Roman ideals surrounding the body was emblematic of a broader societal fascination with all things from antiquity. A trend noted by Sachs and several others in recent years.

This interest led to arguably the first bodybuilding spectacle when Andrew Ducrow performed in Dublin under the billing of ‘The Living Statue or Model of Antiques.’ An equestrian performer by trade, Ducrow was among the first to take advantage of a growing interest in the body as forged through Greco-Roman ideals.

This interest grew quickly in the British zeitgeist. When the ‘Great Exhibition’ came to London in 1851, the Crystal Palace theatre was adorned with Greco-Roman statues. An inclusion that did not go unnoticed at the time by members of the public. For Budd, the statues became reference points for spectators, from which their bodies were measured and similarly proved influential for fitness professionals. Writing a gymnastics manual for a middle-class audience in 1862, Forrest lamented that while,

We English, possess perhaps the finest and strongest figures of all European nations…We…are apparently devoid of that beautiful series of muscles that run round the entire waist, and show to such advantage in the ancient statues…[emphasis added]

We see then that a relationship between the statues of antiquity and modern health was forged during the nineteenth-century, especially from the mid-century onwards. Such a relationship was of utmost importance to the ‘forerunner’ or ‘father’ of modern bodybuilding as he is often termed, Eugen Sandow.

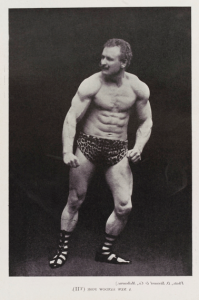

Propelling himself in to the English public sphere at the turn of the nineteenth-century, Sandow was one of the most recognisable faces of physical culture during the opening decades of the twentieth-century. What separated Sandow from the many strongmen operating in England came down to his enviable physique. An enviable physique he displayed in direct comparison to the artful works of Greece and Rome.

The two photos, emblematic of Sandow’s wider catalogue walked a tight line between art and obscenity. A tightrope that Sandow managed to traverse owing to his continued reference to the states of yore. This tactic, though perfected in many ways by the Prussian, would see Sandow and his competitors regularly appear in loincloths or fig leafs as an homage to the Homeric period. Thus, the first posing trunks in the realm of bodybuilding were artistic in design.

- ‘Professor Atilla’ in rather more modest loincloths, c. 1890s

Bodybuilding as Commerce

Now of course Sandow’s emergence on the health sphere was not solely altruistic. It was driven in part by the Prussian man’s desire to turn a profit from his physique. An intention that leads neatly into the second aspect of bodybuilding to be discussed, bodybuilding as commerce.

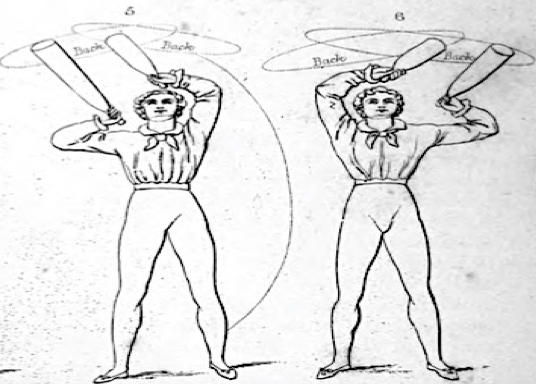

From the beginning of the nineteenth century, English readers had been treated to a plethora of exercise manuals aimed at improving their physiques, copperfastening their health and bestowing on them a host of vague attributes ranging from ‘manliness’ to ‘vigour’. What is significant about such works, aside from their very obvious societal cues, were the bodies or physiques utilised to illustrates the exercises. Two of the forerunners in this regard were P.H. Clias and Donald Walker, both of whom published such works in the opening decades of the nineteenth-century. Regarding the latter’s work, ‘British Manly Exercises’, a relatively tame approach was taken with regards to the display of physiques

- ‘Exercises Five and Six’, Donald Walker, British Manly Exercises: in which rowing and sailing are now first described, and riding and driving are for the first time given in a work of this kind…(London, 1834), 26.

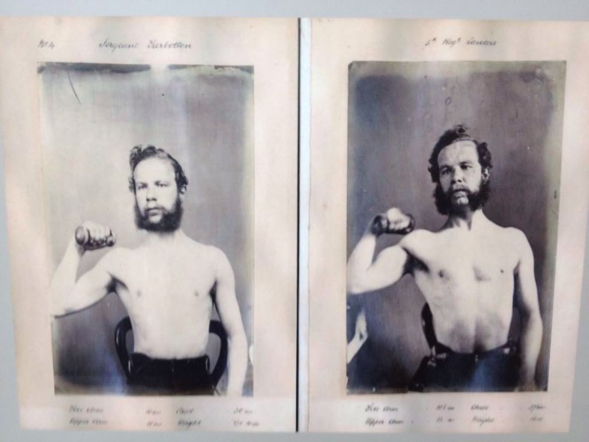

Published in the early 1830s, Walker’s work was emblematic of a public sphere that was only beginning to welcome depictions of the muscular male physique in action. Those publishing in Walker’s wake however, found a much more receptive audience vis-à-vis male flesh. By the 1850s, it was permissible for Archibald MacLaren to display before and after photographs in his training manuals of half-stripped men posing. Shown below, the men’s ‘trunks’ are just your average trousers. Far removed from the Sandow’s artistic loincloth or fig leaf.

- One of MacLaren’s Students, Courtesy of the Royal Army Physical Training Corps Museum, Aldershot

Others, both within England and further afield, echoed MacLaren’s tentative showing of the male physique. For example both the English strongman ‘Professor Harrison’ and the American physical culturist D.L. Dowd, displayed both their own and their pupils’ physiques using regular trousers or trunks. A deviation from the bodybuilding as art trend discussed previously.

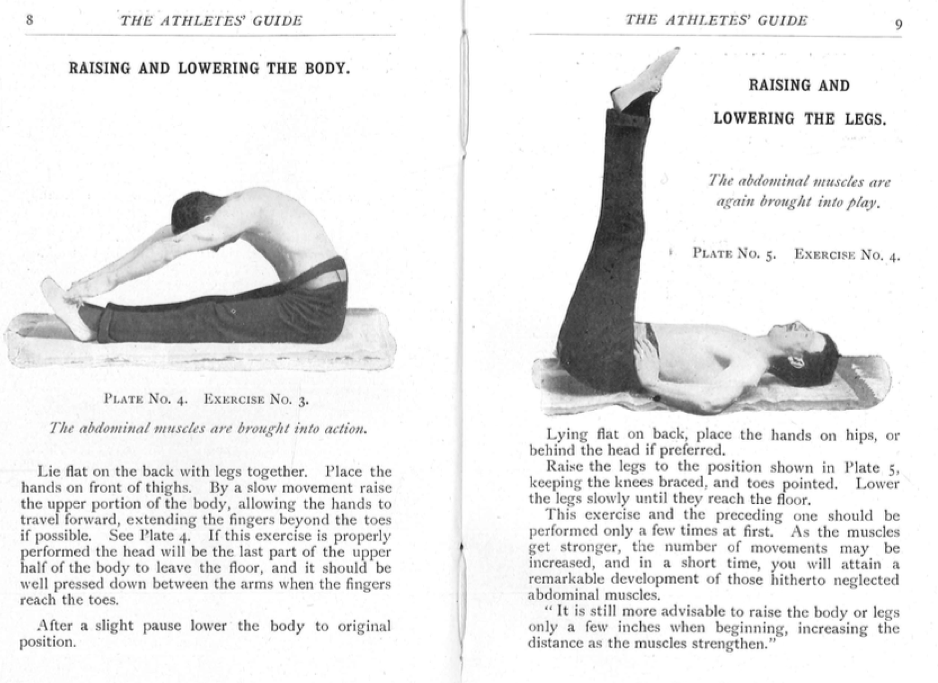

This line of display continued well in to the opening decades of the twentieth-century where it was commonplace to see trunks or trousers publicised within the pages of training manuals. In 1908, the Irish physical culturist, G.S. Greene used photographs of men half naked men wearing trousers to display his exercises.

- G.S. Greene and P.A. Marrinan, The Athletes’ Guide to Health & Physical Fitness (Dublin, 1908), 8-9

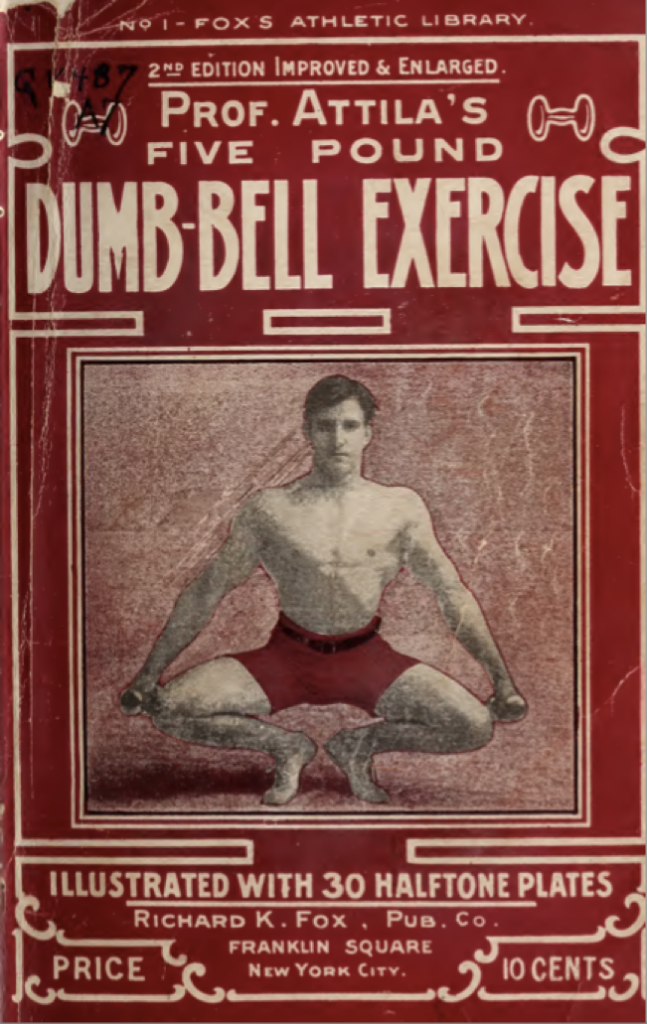

Writing in 1913, Sandow’s mentor Attila likewise used photographs of men in shorts

- Prof Attila, Five Pound Dumbell Exercises (New York, 1913), Front Cover

Thus one sees a split of sorts in the early decades of the twentieth-century whereby some chose to display the male physique using fig leaves and loincloths inspired by antiquity. Others chose to use rather more modest trousers and shorts. Such a diversion, although still tentatively in existence, did not last the test of time. As bodybuilding moved more towards competition, traditional bodybuilding manuals began to feature the champions of the day. As these champions donned posing trunks or in later decades thongs, so did the manuals become infiltrated with increasingly naked, albeit muscular men. A history to be unpacked in the second part of this series.

Article © Conor Heffernan

Sources

Printed Material

Budd, Michael Anton, The Sculpture Machine: Physical Culture and Body Politics in the Age of Empire (New York, 1997).

Chapman, David L., Sandow the magnificent: Eugen Sandow and the beginnings of Bodybuilding (Illinois, 1994).

Forrest, George, A Handbook of Gymnastics (London, 1862).

G.S. Greene and P.A. Marrinan, The Athletes’ Guide to Health & Physical Fitness (Dublin, 1908), 8-9.

Prof Attila, Five Pound Dumbell Exercises (New York, 1913).

Professor Harrison, Indian Clubs, Dumb-bells and Sword Exercises (London, 1865).

Roach, Randy, Muscle, Smoke and Mirrors, Volume One (Bloomington, 2008).

Sachs, Jonathan. “Greece or Rome?: The Uses of Antiquity in Late Eighteenth- and Early Nineteenth-Century British Literature.” Literature Compass 6 (2009): 10.1111/j.1741-4113.2008.00612.x

Todd, Jan. Physical Culture and the Body Beautiful: Purposive Exercise in the Lives of American Women, 1800-1870. Mercer University Press, 1998.

Walker, Donald, British Manly Exercises: in which rowing and sailing are now first described, and riding and driving are for the first time given in a work of this kind…(London, 1834), 26

Web Resources

Battle for the Gold Documentary (Available on YouTube).

Misc

Royal Army Physical Training Corps Museum, Aldershot.

Stark Physical Culture Archive, Texas.