By Gherardo Bonini,(with special thanks to Mary Carr for the translation)

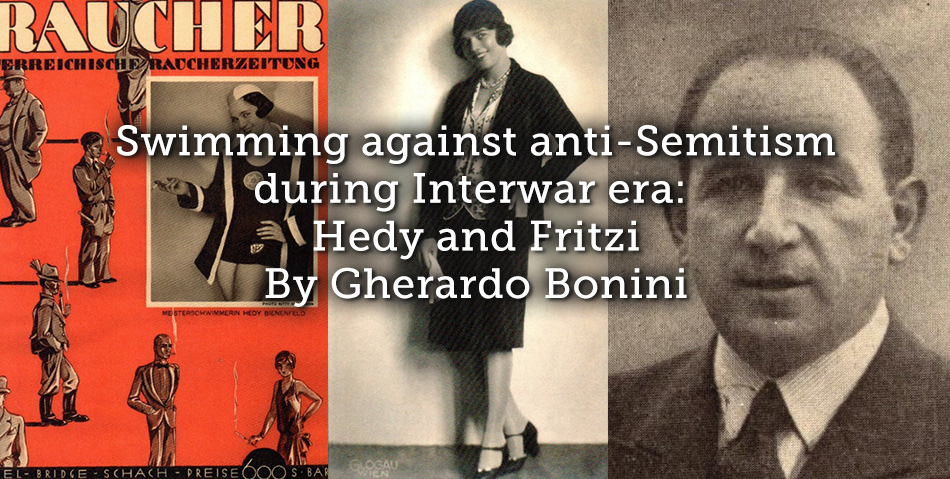

The Viennese athletes Hedy Bienenfeld (1907-1976) and Fritzi Löwy (1910-1994) were the most important Austrian swimmers of the Interwar period. They were close friends and members of Hakoah (Strength), the great Jewish sports club founded in 1909. Both of them won their first national titles in 1925. Fritzi dominated freestyle races, from 100m to 500m until 1934, Hedy the breaststroke until 1933 but also sporadically won backstroke events. Both contributed to winning several Hakoah relays. At international level, they won in Bologna 1927, the only medals secured by Austria in a European championship until 2000.

- Hedy and Fritzi awaiting the start for Through Vienna 1926

However, the hardest battle they fought was against anti-Semitism which was emerging in the main competitions of the time, with the cosmetic changing of the rules, the failure to recognise certain records which made their selection for Austria almost impossible. Initially, Hakoah responded to the discrimination in the form of boycotting some competitions etc, and later by trying to improve their performances, as winning meant surviving. After World War I, the Austrian swimming federation (VÖS), which in principle was not supposed to be anti-Jewish, was made up by, judges, officials and also journalists, failed to appreciate the Hakoah swimmers’ triumphs especially from 1925 onwards, in particular the female section. Zsigo Wertheimer, Hedy’s husband from 1930, trained his swimmers hard with difficult workouts and almost maniacal refining of strokes and moves.

- Zsigo Wertheimer (the trainer and Hedy’s husband from 1930)

In 1932, the pro-Nazi First Viennese Swimming Club (EWASK) took over the running of VÖS. Life became even more difficult for the Jewish athletes. Fritzi and Hedy were able to pass the severe selection tests, only failing when they weren’t at optimum fitness levels. Following a controversial match in water polo, Hakoah was sanctioned, it was during this time that Hedy improved two national records, but EWASK disguised as VÖS ignored these achievements. It was not first time, Fritzi previously established two European records, the second one recognized by the European federation (LEN), but no Austrian journal published this information, only European readers of specialized journals found out about the records. The Deutschösterreichische Zeitung, a pro-Nazi journal, declared Fritzi’s victories “a shame for the nation”. But Fritzi outshone all her rivals, meaning no one could question the titles.

And as for Hedy? In her races, results were decided by tenths of seconds – in 1922 she finished first but in a dead heat, the rules allowed for a dead heat victory but the referees decided that the race was to be re-swum, Hedy lost that race. In 1923 she was first in front of Lotte Karsten, but she touched the pool wall with her feet, as swimmers had done in the past. Hakoah officials explicitly asked one judge if the touch was permitted, he responded affirmatively. The other referees however, ordered a re-match. Hakoah asked Hedy to not race in the replay and appealed the decision. Karsten did not race a second time either. The Jury accepted the protest, cancelled the results of the second race, disqualified Hedy and proclaimed Karsten the winner. On 14th August 1927, the results of the 100m backstroke championships were nullified because the eventual winner Gusti Fleischer, Hedy, and the future successful soprano Hilde Konetzni kept bumping into each other. Hakoah asked to host the rematch and on 1st October Hedy clearly won. But the press stressed “it was not a true championship”, defining Hedy’s victory belanglos (without significance). In the 1928 championships, Hedy won again but at the start she used a double stroke and was disqualified. The press opposed the double stroke, VÖS also had voiced it’s opposition, but the rulebook still permitted it’s use. This time Hakoah won the appeal… for applying the rule. It is worth noting that when other clubs made appeals, the press recorded the procedure as normal. But when Hakoah appealed, this club lacked sportgeist (sporting spirit).

- Hedy, Fritzi and Roeders, the first three of Through Vienna 1926

On 28th April 1929, Hedy set the Austrian 500m breaststroke record – to nine minutes. In the spring of 1930, LEN inaugurated the official list of European records for that competition. The first recorded time was 10.33.2. No Austrian delegate pointed out that a record had already been set in the 500m breaststroke for some years. Sometime before, Fritzi suffered a similar injustice – her first European record for 200m remained unofficial, the second one, 500m in 1927, was only recognized in 1929 because an Austrian delegate questioned the final decision. Hedy unfortunately did not receive the same treatment.

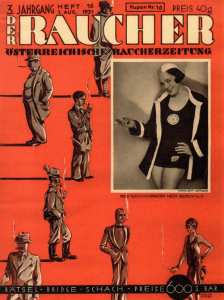

At the turn of the 1930s Hedy has become an icon of beauty. She worked in a clothes shop, modelling bathing costumes and suits, which sold out rapidly. In 1932 in Krems, she won the long distance championships crossing the line, but not in the narrow and unmarked space between two pontoons, just like other swimmers had done in the past such as Fleischer who won in 1931. Just after the end of the 1932 competition, a Nazi group attacked Hakoah swimmers and assaulted the Hakoah athlete Fritz Lichtenstein, who luckily managed to escape by car, along with Hedy. Needless to say, EWASK disguised by VÖS stripped Hedy of the title.

- Hedy in the The Smoker (Der Raucher) journal

- Hedy modelling clothes

As previously stated, controversy coloured the backstroke championships of 1927 and 1928. In 1937, EWASK published a jubilee book to mark its 50th anniversary. The publication reported lists of previous championship winners. Hedy was deprived of her two backstroke titles. Fortunately, other publications were compiled using a true history, but the last historic book on Austrian swimming in 1999 did a “cut and paste” from the EWASK book for the 100m backstroke. Is it the case to reveal the truth?

In her last competitive year in 1937, Hedy surprised the Austrian swimming field once again. No other Austrian woman breaststroker had attempted to use the new butterfly stroke experimented with in the United States and Germany. Zsigo suggested to Hedy that she give it a try. Hakoah was undergoing a difficult period at that time, the three new stars of Hakoah, Deutsch, Langer and Goldner had been disqualified before the Berlin Olympics because they refused to compete in a country that discriminated and humiliated the Jewish population. Hedy set a new 100m record and narrowly missed that of the 200m. Although 30 years old and with a 15-year career in swimming, she returned to the limelight and Hakoah had once again something to be proud about. The Anschluss however destroyed Hedy’s dream of redress and she escaped with Zsigo to the United States, where Zsigo died in 1965. Hedy come back to Vienna where she met up again with Fritzi, who fortunately had also survived the war.

- Postcard sent from USA to Fritzi by Hedy and Zsigo in 1955

Article © Gherardo Bonini

![Playing Football with the Chorus Girls: <br>Vaudeville Women’s Football in Naples [1931]](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/PP-banner-maker-440x264.jpg)