The summer of 2016 witnessed the hundredth anniversary of the Battle of the Somme, the most horrific encounter of World War One, which claimed over a million casualties along a 15-mile front in 141 days. Had war not broken out in 1914, the world might have reflecting upon the centenary of the 1916 Olympics, which were due to be held in Berlin that summer but cancelled as a consequence of the war. From analysing the initial preparations of several major Olympic nations, these Olympics had the potential to be very different to those which had taken place before.

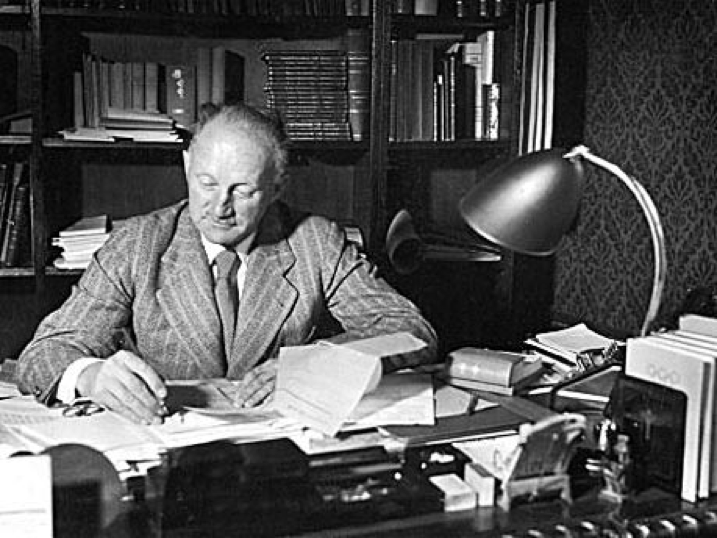

Berlin had been selected to host the sixth Olympiad following selection at the 14th session of the IOC, which took place during the 1912 Stockholm Olympics. In order to host, the German capital had defeated stiff competition from Alexandria, Amsterdam, Brussels, Budapest and Cleveland (Ohio). In the words of German Olympic Committee member Carl Diem, the Games would be used as ‘a medium to convince the people of our worldwide importance’, a clear statement of German intent.

- Carl Diem

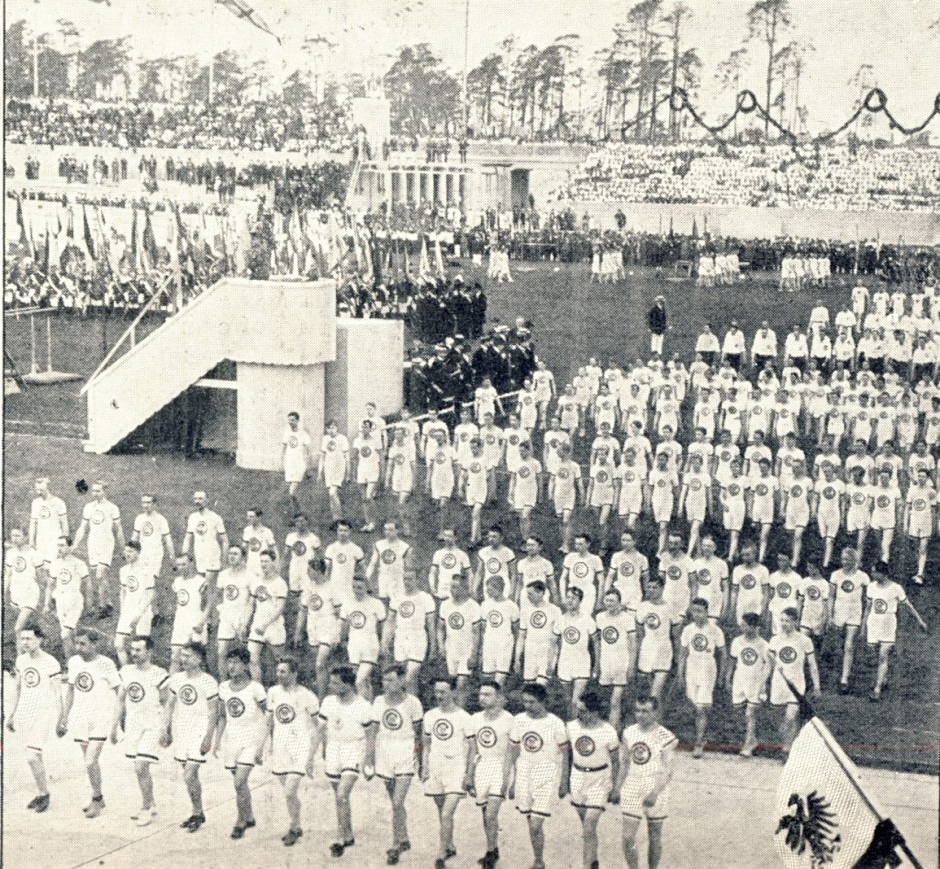

Just a year after Berlin was awarded the Games, their principal venue the ‘Deutsches Stadium’, was opened as part of the Kaiser’s 25th anniversary celebrations as Head of the German Reich. The Stadium’s design mirrored the White City Stadium in London, host of the 1908 Olympics, and so not only had an athletics track, but also a velodrome, swimming pool, playing field and stands with room to accommodate over 60,000 spectators.

- Athletes march during the grand opening of Berlin’s Olympic stadium, on June 8, 1913 @PhilBarker

This new magnificent stadium was just part of Germany’s attempts to demonstrate its prowess, as plans had also been made to guarantee its athletes could compete alongside the world’s best. In a desire to ensure this, the German Olympic Committee undertook a tour of the United States of America, the world’s premier athletic nation in the summer of 1913, ‘with a view of studying conditions in the field of American athletics’.

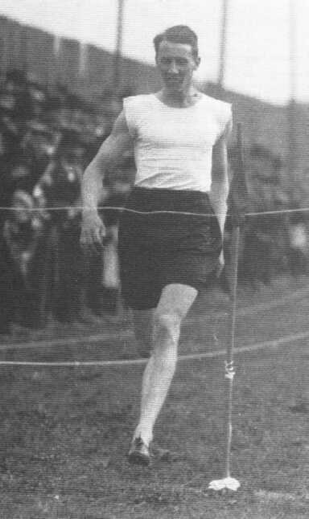

The most significant outcome of the tour, where the Committee visited many top colleagues and athletic meetings, was the appointment of a track and field coach to prepare Germany’s athletes for the Berlin Olympics. The coach selected was, Alvin Kraenzlein, who immediately left his job as Head Coach at the University of Michigan ‘to prepare and train the German athletes for the Olympic Games to be held at Berlin in 1916.’ Kraenzlein, the winner of four gold medals at the 1900 Olympics in hurdling by using his revolutionary technique of hurdling with his lead leg extended, was not only an obvious candidate due to his prowess on the track and experience as a coach, but also because he came from German heritage.

- Alvin Kraenzlein

Kraenzlein’s mandate was to improve the performance of Germany’s track and field athletes in Berlin, who had underperformed in Stockholm. This team had won just two silver medals (from Hanns Braun in the 400m and Hans Liesche in the high jump), leaving Germany ninth in the athletics medals table and no doubt a repeat performance in Berlin would represent a national embarrassment. This appointment was an attempt at copying the methods which the United States had pioneered and Sweden had successfully adopted for their own Olympics.

- Hanns Braun

- Hans Liesche

A newspaper article describing his appointment explained that Kreanzlein’s contract was for 5 years at $10,000 a year. This perhaps was money provided by the ‘German Count’ who donated $75,000 to the German OC in September 1913 (Toront0 Sunday World, 23 September 1913).

At the end of the American tour Carl Diem described the American system as ‘perfect’. He clarified that the appointment of Kraenzlein was made ‘so we shall be able to undertake the world of preparing our athletes upon modern lines and thereby produce a formidable team by 1916’. When the German delegation left the United States in the Fall of 1913, Kraenzlein returned with them to take up his new post in Berlin.

Germany was not the only nation who had put plans in a desire to ensure Olympic success, as its European rivals had also set about making their own plans ready for the showdown in Berlin. Britain’s performance in Stockholm had been disastrous (with just two gold medals won in athletics) and there was a strong desire to improve athletics performance in order to get ‘a bit of our own back that wrested honours from us in the Stadiums of Shepherd’s Bush and Stockholm.’ One idea seriously floated within the British press was that Britain’s athletes would compete within a ‘British Empire’ team which incorporated men from the Dominions as well. Despite merits in this idea, those organising the British Olympic Team found it to be unfeasible and more practical means of improving British performance were sought.

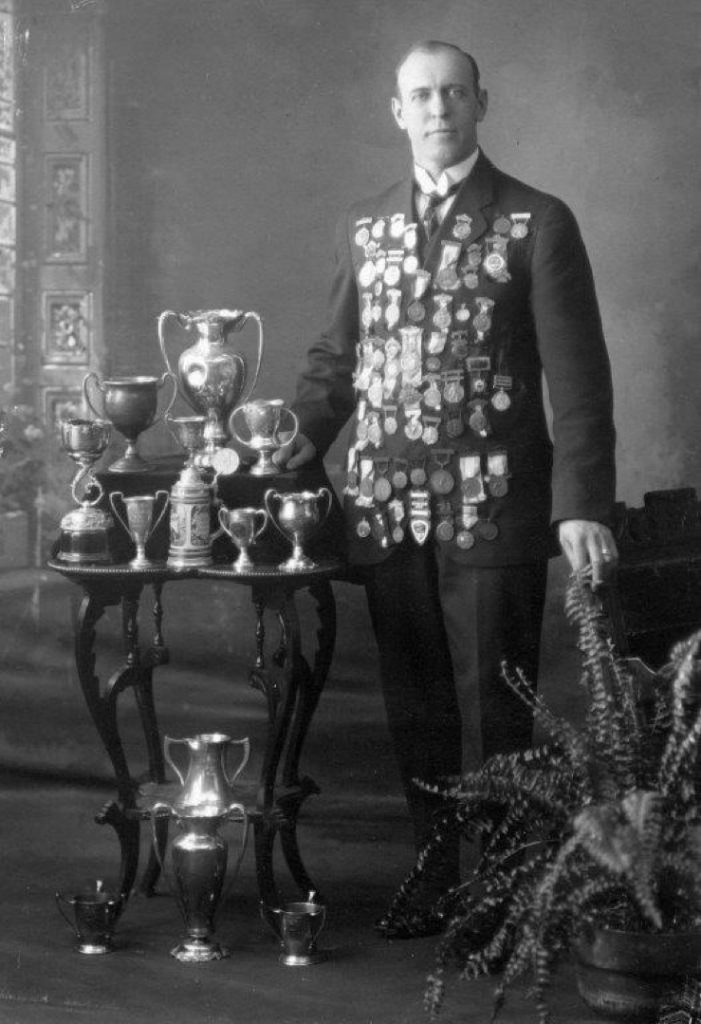

Poor organisation and a lack of financial backing were major reasons in the British preparations for Stockholm and the ‘Special Committee for the Olympic Games of Berlin’, established in 1913 sought to tackle these issues. Although the committee was not entirely successful in raising the amount of money they desired, the money that was raised allowed Britain to appoint its first ever professional trainer to try and compete with her sporting and military rivals. In early 1914 Walter Knox, a Scottish-Canadian a two-time professional world champion all-round athlete, was appointed to the position. This was an appointment directly comparable to that of Kraenzlein in experience and the fact that both men were of North American stock, so knowledgeable in the successful American training methods.

- Walter Knox

Hosts of the 1912 Olympics, Sweden, had employed five professional coaches for the Stockholm Games and preparations for Berlin were to be organised in a similar manner. Although unconfirmed, there were reports that the French Government was to give $100,000 to help its Olympians prepare. If true, this money represented a significant amount and would have allowed training on similar lines to that proposed by Germany. These preparations show some evidence of the major nations of Europe beginning to take their political and military rivalries onto the athletics track.

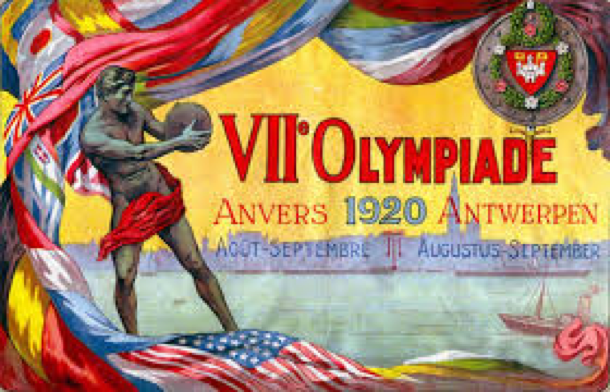

Despite the hopes that the Games could take place despite the war, possibly in another location, such as Chicago, plans for the 1916 Olympics were eventually abandoned. It would not be until 1920 and the Belgium city of Antwerp that the athletes of the world would once again converge at Olympic Games. Despite not taking place, the 1916 Berlin Games are still considered as the Sixth Olympic Games. Berlin would have to wait until 1936 to host the Olympics, and when it did these would take place in a Stadium built upon the site of the ‘Deutsches Stadium’.

- Poster for the Antwerp Games

Although we can only prophesise what would have happened at the 1916 Olympics had they gone ahead. What is clear from the movements that had taken place in the period between the Stockholm Olympics of 1912 and the outbreak of war in July 1914, that these had the potential to be very different Olympic Games.

The five nations mentioned above had begun preparations for the 1916 Olympics with more intent than had been previously seen. The potential was for these Games to become reflective of international rivalries and the first truly modern Games in terms of a representation of wider international struggles. If they had taken place, the athletes would have been amateur in theory, but their preparations would have been anything but, having been administered and monitored by professional coaches.

The Berlin Olympics of 1916 could have issued a new era for the Olympic Games. The war meant that the 1920 Olympics would be a step back from the preparations of Berlin, and the Olympic Games would take longer to become representative of national rivalries.

Article © Luke J Harris