To read Part 1- click HERE , To read Part 2 – click HERE , To read Part 3 – click HERE

Image 1: Clarice in her A.T.S. uniform as the Zone Recruiting Officer for Liverpool

Liverpool Echo 22 April 1941. With thanks to the British Newspaper Archive

Clarice’s path to wartime success started in peacetime, when on the 15 November 1938 she was gazetted as a Junior Commander in the fledgling Army Territorial Service. (A.T.S.).[1] The bare details of her military career show her rising through the following ranks and postings.[2]

1940 – October – now Officer Commanding 1st Wiltshire Platoon ATS.

1941 –April – Liverpool – appointed Zone Recruiting Officer.

1941 – December – Manchester – appointed Assistant Chief Recruiting Officer for the Northwest. Also promoted to rank of Chief Commander.

1942 – August – Manchester – appointed Chief Recruiting Officer for the Northwest.

1946 – referred to as the A.T.S. Recruiting Officer for the Midland Area.

She ended the war as a Chief Commander, the equivalent of a male Lieutenant-Colonel. Such a man would command an individual infantry battalion or cavalry regiment of 500 to 1,000 men. Her area of responsibility was recruiting, and she was the chief officer at various times for the North-West and the Midlands. If there was a period when Clarice’s organizational talents were best recognized, this was it.

What follows is an outline of her military career, as I have not yet been able to access her Service Record. However, by combining contemporary newspaper records, archival sources from the National Army Museum, and modern research by writers like Professor Lucy Noakes, it is possible to sketch its development and explore how it reflected key challenges that the A.T.S. faced during the war.

The A.T.S. was borne out of Britain’s experience of the First World War and reflected contemporary concerns and prejudices about recruiting women to the armed forces. This was the first time that the Army had recruited a women’s unit and by 1918 there were 38,901 women in the Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps (QMAC). But, as Lucy Noakes describes, after the Armistice there was a quick shift ‘towards a concern that it was essentially unfeminine, a threat to the gendered status quo,’ and they were disbanded.[3] Female interest in auxiliary military service remained though throughout the inter-war period and various groups such as the Voluntary Aid Detachment, First Aid Nursing Yeomanry, Emergency Service, and Women’s Legion were merged into the A.T.S., which was formed by Royal Warrant on 9 September 1938. Its Commander-In-Chief was Helen Gwynne-Vaughan, who had held senior positions in the QMAC and the Women’s Royal Air Force (WRAF) during the First World War.[4]

At its peak in June 1943, the A.T.S. numbered 214,420, making up 7.35% of the overall total of the British Army at that time.[5] They went from providing a limited range of roles to over sixty diverse types. Most notably, from 1941 onwards they could join anti-aircraft batteries and served under fire. Although they were allowed to load and aim guns, they were not allowed to fire them. Such service played an important part in freeing male soldiers for overseas service. Some A.T.S members also served overseas themselves.

Although it played its part in the war effort, the A.T.S. suffered throughout the war as the poor relation of the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WREN’s) and the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF). It faced interconnected problems with recruiting, retention, and its public image. Noakes describes how the War Office intended to use the same leaders and same gendered roles from the First World War and ‘thus began on a shaky footing, hidebound by attitudes to class and gender which had more in common with the society of the First World War than the Second.’[6] Until 1941 they were only allowed to work in non-operational support roles in five trades: clerks, cooks, store-women, drivers, and orderlies, roles that were seen as belonging to the ‘female sphere.’[7] This hampered early recruitment with the A.T.S. seen as, ‘little more than general handmaids to officers and even their wives.’[8] In addition, the organization was still heavily structured along class lines, with titled ladies predominating in senior positions. The uniform was also very unpopular, seen as inferior to Navy and RAF alternatives and described by one recruit as ‘stupid and inelegant.’[9] The idea of female military service also saw a replay of complaints and prejudices articulated during the First World War against ‘frivolous’ femineity, recruits being too masculine, and the encroachment of the state on the private world of gender relations. Those who were dissatisfied could vote with their feet, as they were free to leave. Between September 1939 and December 1940, the intake of 31,960 was balanced by 13,212 departures, approx. 40% of the overall strength.[10]

How did Clarice come to join the A.T.S and become a Commander so early in her career? While we do not know the exact circumstances and motivations, her relatively longstanding and successful involvement with the Conservative Party is most likely the key factor here. As well as revealing her political leanings, it presumably also connected her with the types of ‘County Leader’s’ that Helen Gwynne-Vaughan preferred to recruit at the local level, feeling that ‘patriotism is more foreseeing among educated people.’[11] Her attendance at Ashridge College potentially developed her leadership skills while developing her political contacts. Given her political outlook and connections, her clear administrative abilities, her husband’s standing in the local community, her suitable age, and presumably good social skills, she clearly possessed enough about her to be deemed suitable officer material from the start.

Newspapers provide tiny glimpses of her time with the 1st Wiltshire Platoon in 1940 and 1941. Given the challenges faced in retaining recruits, it is interesting to see Clarice’s use of the North Wilts Herald to appeal to the public for musical instruments to help entertain her Platoon and later thanking the donors of three pianos and the paper itself in October 1940.[12]

We get a several brief mentions of Clarice in March 1941, both related to her efforts to get new recruits. The North Wilts Herald reported on her latest recruiting efforts, which included her own daughter Margaret.

SISTERS IN THE A.T.S.

The Misses Williams of Swindon

During her occasional visits to Swindon, Mrs. Ted Vizard, junior commander of the A.T.S., who is in charge of the 1st Wilts Platoons, always succeeds in recruiting a few more girls. They are immensely happy and efficient in their new (illegible text) she says, and all are in robust health. Perhaps the popularity of the service could best be illustrated by the fact that the girls are bringing their sisters along There is a trio of Swindon sisters with the 1st Wilts – Joan Williams, a senior leader, Violet, a sub-leader. and Dorothy a volunteer. They are daughters of the late Mr. Charles Williams, the well-known footballer and cricketer, who, at one time, kept the County Ground Hotel at Swindon. Their brother, Charles, is a Quartermaster-Sergeant in the Army.

Miss Audrey Vizard daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Ted Vizard, has given up her appointment in Lloyds Bank to join the 6th Gloucester Company of the ATS., and will shortly commence her training. Mother and daughter will thus be in the same branch of the women’s service.[13]

Elsewhere, the Bolton Evening News covered her visiting the town on leave and explaining that she:

Would not be averse to taking a few Bolton recruits back with her as cooks, clerks, typists, and orderlies. “It’s a grand life,” she declares, “and no girl who has decided to try it would regret it.” Mrs. Vizard’s daughter has given up a job in a Swindon bank to join the ranks. There are already one or two Bolton girls where Mrs. Vizard is stationed, and she had vacancies in her own company.[14]

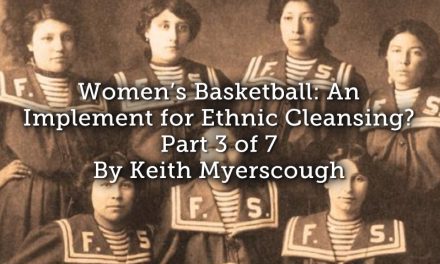

One of the highlights of Clarice’s military service came shortly afterwards, when in April 1941, the King and Queen toured Southern Command.

Image 2: The Sketch, 16 April 1941.

With thanks to the British Newspaper Archive

While the main focus of contemporary media coverage, such as that in the Sketch, Tatler or in Pathe Newsreels (see – https://www.britishpathe.com/asset/66089/ ), was on demonstrations of male military might, the North Wilts Herald picked out the Royal couple’s engagement with Clarice’s A.T.S. platoon.

THE QUEEN AND THE ATS

During their visit to the Southern Command on Thursday last, the King and Queen were particularly interested in the girls of a Wilts platoon of the ATS most of whom are from Swindon and district.

Junior Commander Mrs. E. T. Vizard who had personally recruited many of the girls, had the honour of showing their Majesties round examining the routine of camp life the many duties and responsibilities that belong to the platoon. At present, for instance, they are cooking and serving the meals for 500 men, and eventually the number may increase to 1,000. In addition, they are called upon to provide clerks and typists for the Supplies and Transport Section of the R.A.S.C. to which they are attached.

The Queen was especially interested, and remarked upon the cheery efficiency of the girls, their smart appearance and obvious devotion to their duties.[15]

It is perhaps no coincidence that, presumably having ensured a satisfactory display by her unit to their Majesties, that Clarice was soon promoted to a new role as a Zone Recruiting Officer in Liverpool.

Clarice’s promotion came during a key period of change in the A.T.S. leadership and its place in the war-effort. In March 1941 all women between 18 and 45 ordered to register at their local employment exchange to that they could be directed to essential industries. In April, the A.T.S. was incorporated into the Army Act which gave them full military status and ending the appointment of officers by virtue of birth and background. Instead, as Noakes describes, they ‘had to go through a lengthy selection process which included examinations, public speaking, practical tests, and psychological assessment.’ In July, Gwynne-Vaughan, increasing out of step with the needs of a ‘People’s War,’ retired, and Jean Knox took over as Commander-in-Chief. Noakes describes how, ‘Knox, younger and more archetypically feminine than the militaristic Gwenne-Vaughan, oversaw a redesign of the A.T.S. uniform along more feminine lines.’ Finally female conscription was introduced in December 1941. The National Service (No.2) Act called up all unmarried women between the ages of 20-30. Women were allowed to volunteer to serve at anti-aircraft sites but were not permitted to fire weapons.[16]

Despite these various changes, the A.T.S. still faced challenges in recruiting and in its public image. Recruitment rose but was still well below the War Office target of 5,000 per week. A Ministry of Information survey found that the public still thought they were mainly employed as cooks, while men viewed them as comprising lower-class recruits susceptible to drink and promiscuity. A recruiting drive was launched in 1941 through posters, radio broadcasts, and newspaper articles with the aim of emphasising both the femininity of A.T.S. members and variety of roles available. A fine line had to be trod though, with one official war office poster withdrawn because it was deemed ‘too daring for public consumption.’[17]

Image 3: A.T.S recruiting poster by Abram Games

The ‘Blonde Bombshell’ image was initially popular, but it was later withdrawn.[18]

National Army Museum. NAM: 2013-07-2-17

Her work as a recruiter can be glimpsed through interviews and reports in the regional press as she sought to encourage recruits to join the A.T.S., encourage civic leaders to help share her message, and to reassure parents about the respectability of military service. An early example comes from an interview she provided to the Liverpool Echo and published on the 22 April 1941.

Jobs in the A.T.S.

Chances for all kinds of ability

Thousands of recruits are needed for the A.T.S., and, to help and direct the recruiting drive on Mersey side Mrs. E. T. Vizard late Junior Commander and Officer Commanding the 1st Wiltshire ATS has come as Zone Recruiting Officer. She knows the North well, especially Bolton for her husband is the famous footballer, who now manages London club, Queen’s Park Rangers. Aware that the girls and women of Merseyside naturally have a leaning towards the “Waafs” and “Wrens” because of the district’s geographical position, she has faith that the A.T.S. will get its fair share when its work is truly appreciated. “I know,” she says, “that the blue uniform appeals, but khaki looks very business-like, and I can vouch for its serviceability. Perhaps the original khaki skirts were not so immaculately cut as they might have been, but there is nothing wrong with the new design.

Our new forage cap is going to catch the eye, too. Women naturally have a quick appreciation of fashion, but there is more to what we can do to help the country than to what we shall wear while we do it.

Cooking is not the only job in the ATN. We want more cooks, but also typists, clerks, motor-drivers, and girls who can take highly-specialized courses of training.

“For some time we have been training picked girls in the kine-theodite units. You need brains and dexterity of fingers for this job of recording and calculating A.A. gunfire. There must be many talented girls on Merseyside who could take up this vital work. “It’s a grand life in the A.T.S. I say it with conviction. My daughter came to have a look at us and the next thing I knew was that she had resigned her job in a bank and donned uniform. I’m looking forward to a fine response in this area.”

Recruits should apply at Renshaw & Hall or at the Depot. 96 London Road, Liverpool.[19]

The Liverpool Echo quoted her again on the 2 September 1941, when Clarice emphasized the increasing number of role available to recruits, including those at anti-aircraft batteries.

GIRLS ARE “REAL SOLDIERS”

100,000 OF THEM WANTED FOR THE A.T.S

“One hundred thousand girls are wanted for the ATS before Christmas,” said Mrs. Vizard zone recruiting officer for the A.T.S. Speaking at the Liverpool Soroptimist luncheon, held in Reece’s banqueting hall, to-day.

Mrs. Vizard said there was plenty of scope for promotion in the A.T.S Girls did not join the Service without knowing what it entailed, for to-day an ATS girl was a real soldier coming under military law. This, she thought, was to the benefit of the girl, it not only safeguarded her, but under military law she could always get justice.

In some batteries the girls actually gave the order to fire,” and other batteries were staffed by equal numbers of men and girls.[20]

A little later, the Runcorn Weekly News recorded her giving a ‘very interesting address’ to the Townswomen’s Guild that left its members keen to pass on the information they had gained ‘and so dispel any doubts parent might have with regard to encouraging their daughters to join the forces.’[21]

Clara’s efforts were presumably well received, as in December 1941 she was promoted to Assistant Chief Recruiting Officer for the Northwest, moving from Liverpool to Manchester.[22] Clarice also made the news that month when she was involved in a car-accident connected to the blackout. This was introduced to reduce visible lights that could help enemy bombers identify targets. However, it was a major inconvenience, with one in five pedestrians injured in some way by related accidents by 1942. Car accidents also increased dramatically, with 1,130 deaths in September 1939 compared to 544 in September 1938. Clarice was driving her car when a motor lorry driving in the same direction collided with her, ‘the car then hit and demolished a traffic bollard in the middle of the road, but although the car was badly damaged at the front and rear, Mrs. Vizard was unhurt.’[23]

1942 was a significant year for Clarice in two ways. Firstly, in August she was promoted to Chief Recruiting Officer for the Northwest. By this time, her daughter Margaret was also working in A.T.S. Northwest Recruiting Division. Secondly, Clarice and Edward celebrated their Silver Wedding anniversary at the end of the year. The Bolton Evening News note that it took place in London and that ‘it is a reunion because war has scattered the Vizard family. In fact, Mrs. Vizard had had to arrange special leave to be able to enjoy the silver wedding anniversary in her husband’s company.’[24] Lionel was able to attend and was expecting to join the armed forces once his studies finished.

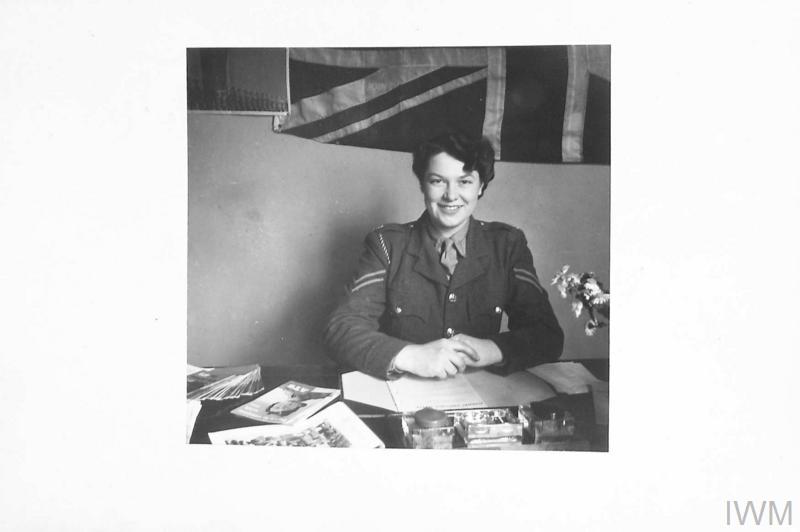

We have a small literal snapshot of Clarice and Margaret at this time thanks to a set of photographs held at the Imperial War Museum. In October 1942, a series of publicity images were taken of ten Recruiting Corporals in the A.T.S. Northwest Division. The were photographed in three similar poses; one by a A.T.S. recruiting poster, arms outstretched to mimic the famous recruiting poster featuring Lord Kitchener in the First World War, and the others sat at their desks. The captions included some personal details and Margaret’s noted that she was a ‘keen amateur actress, she used to play leading parts in Bolton’s Little Theatre Dramatic Society. Her job now is telling Blackpool girls all about the A.T.S.’[25] Interestingly, while it noted her father’s playing and managerial career, it made no mention of the fact that her mother was in the A.T.S. and her commanding officer. Similarly, there was no mention of Clarice’s background when she was included in a group photograph.

- Image 4: IWM, Image: H24892

- Image 5: IWM, Image: H24890

Publicity photographs of Corporal Margaret Vizard, A.T.S. North-West Recruiting Division

Image 6: Clarice Vizard stands at the centre of the Recruiting Corporals

A.T.S. North-West Recruiting Division.

IWM, Image: H24897

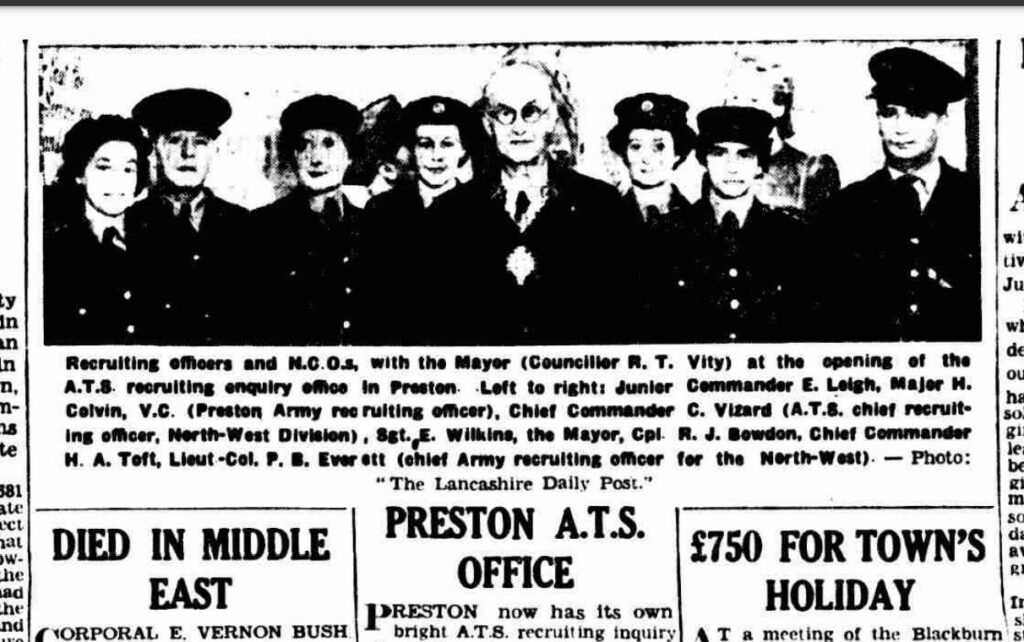

The great bulk of Clarice’s work is hidden from us at present, but we do see glimpses of her public activities after 1942. There are several reports of her opening an A.T.S. office in Preston in March 1943. The Lancashire Daily Post provided the following description.

PRESTON now has its own bright A.T.S. recruiting inquiry office. There is nothing “Army” about this modernistic gaily decorated room in a Fishergate shop.

Royal Engineers did the necessary alterations, and a soldier-artist, Sergeant-Major B. J. Dimond, R.A.O.C., painted murals of remarkable quality-portraits. of the Premier and Mrs. Jean Knox. A.T.S. Chief Controller, and a tableau glorifying the girl in uniform.

Three Preston members of the A.T.S. form the staff of the inquiry office Junior Commander E. Leigh (well-known locally as stage manager of Preston Drama Club), Sergt. E. Wilkins, and Corporal R. J. Bowdon,

The official opening yesterday, was by the Mayor (Councillor R. T. Vity), who commended the facilities of the office as an admirable idea.

PURPOSE OF OFFICE

Chief Commander C. Vizard (A.T.S chief recruiting officer, North-West Division) explained that the opening of the office in the centre of the town was to give entrants all information about their conditions of service and tell parents what kind of training their daughters would have. In the old the days, the AT.S. were only cooks, orderlies, clerks and drivers. Now there were over 80 branches of the Service for girls to pick from.[26]

Image 7: Lancashire Daily Post, 11 March 1941.

With thanks to the British Newspaper Archive

Another report in the Lancashire Evening Post provided a more personal focus on Clarice while demonstrating Ted’s enduring fame.

Ted Vizard’s Wife is A.T.S. Chief

HERE was a gathering of very interesting people at the opening this week of Preston’s new A.T.S. recruiting inquiry office in Fishergate. Chief Commander (Lieut-Colonel) C. Vizard. O.C. recruiting for the A.TS. in the North-West, is wife of Ted Vizard, now manager of Queen’s Park Rangers F.C. in London, who will always be remembered in Lancashire as the famous Welsh international winger, who played for Bolton Wanderers with Joe Smith and all the other stars of those great days a few years after the last war.

She met Councillor R. T. Vity, Preston’s Mayor, as an old friend. He was her former Civil Service superior when he was Postmaster at Bolton. The Vizards, by the way. have a daughter who is also in the A.T.S., and on the way for a commission. Their son is talking a University course in Civil engineering.[27]

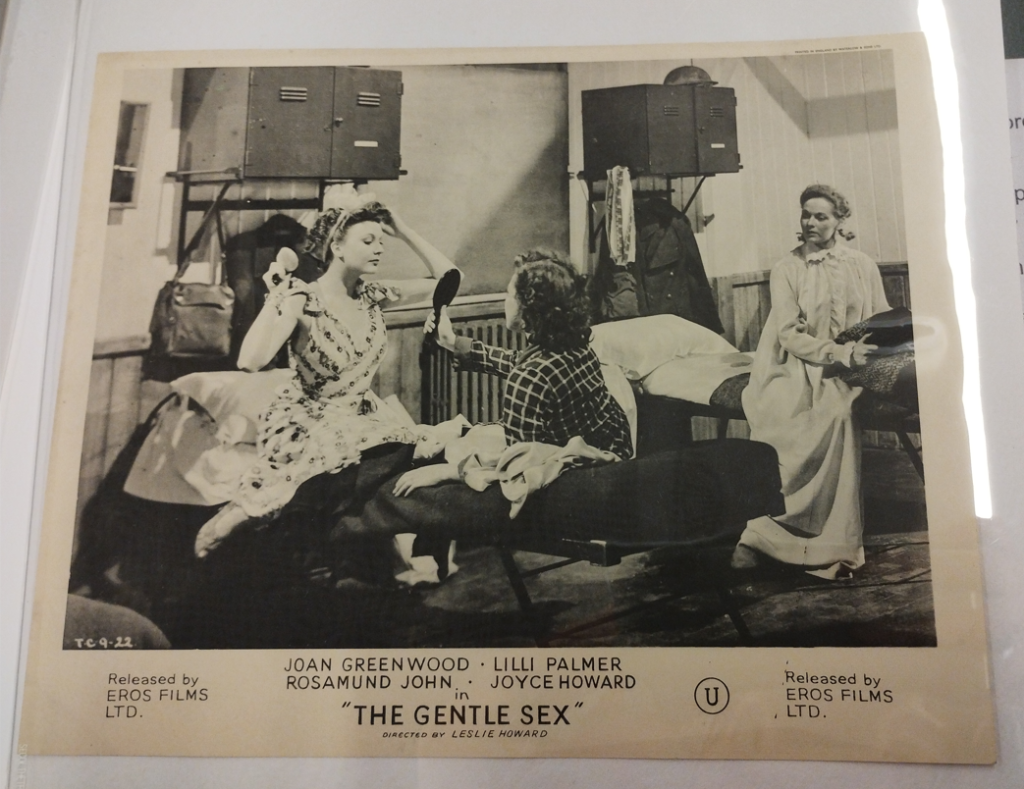

The last wartime reference to Clarice that I have found refers to her attending a screening of The Gentle Sex in 1943. It was directed and narrated by the film star Leslie Howard and Noakes describes it as the film industry’s contribution to trying to improve the public image of the A.T.S.[28] Using elements of documentary realism, it told the story of seven diverse recruits who, in Noakes words, ‘learn the importance of collectivity over divisions of class and character in wartime Britain.’[29] It proved popular with women, with 19 of 104 in a Mass Observation Directive naming it as their favourite film of 1943. Noakes identifies how the film ‘expresses the tensions which existed between women’s new roles as active participants in the war and more traditional conceptions of femininity.’ Part of this was reflected in the Howard’s final speech, which reasserted masculine superiority.

Well, there they are, the women. Our sweethearts, sisters, mothers, daughters. Let’s give in at last and admit that we’re really proud of you. You strange, wonderful, incalculable creatures. The world you’re helping to shape is going to be a better one because you’re helping to shape it. Pray silence gentleman. I give you a toast. The gentle sex![30]

Image 8: Advertising poster ‘The Gentle Sex.’

National Army Museum, 1994-07-2741-46

The release of the film was celebrated with A.T.S. events and the Chester Chronicle records Clarice as part of the high-ranking officials present when 100 A.T.S. members from Western Command Headquarters, Chester Command Sub-District, and the Royal Corps of Signals paraded to the Chester Odeon headed by the Cheshire Regimental Band, where they were inspected by the Mayor and other dignitaries: ‘their smartness attracted a large crowd who remained until the last girl had filed into the cinema.’[31]

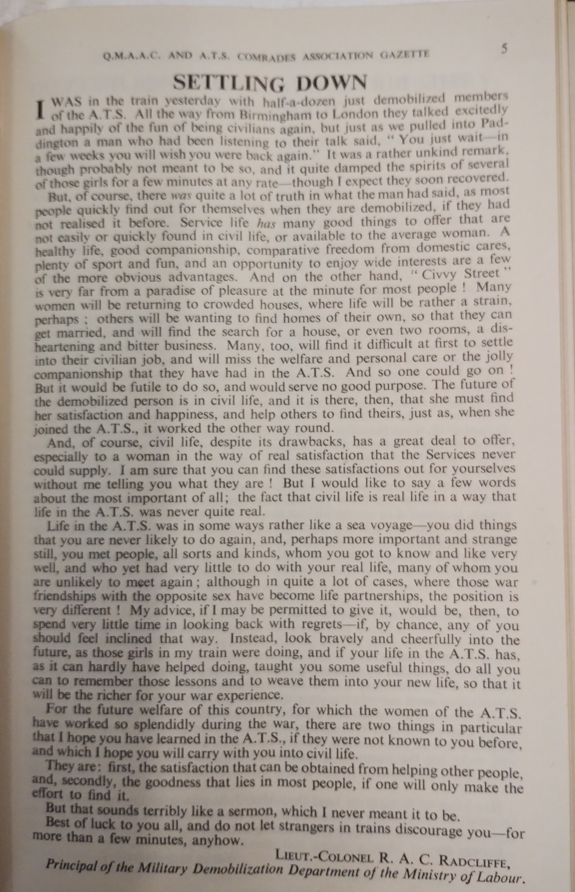

There is one of last sightings of her in the A.T.S. in July 1946 when she helped select a winning Wolverhampton team for a beauty contest with Nottingham at the Nottingham Palais de Dainse.[32] The exact date of her discharge is not yet known, and we cannot be sure how she reacted to the end of the war. But the following article from the Q.M.A.A.C. and A.T.S. Gazette of May-June 1946 gives us a flavour of the time.

Image 9: Q.M.A.A.C and A.T.S. Comrades Association Gazette, May-June 1946.

National Army Museum

While many men and women welcomed demobilization, for others it was a difficult or unwelcome event. Clarice might well have welcomed a return to civilian life and her family home with Edward after being separated from him for large periods of the war. Equally, we might place Clarice within a group of men and women who achieved considerable personal success in their wartime profession, and for whom a return to civilian life meant giving up status and responsibility that could not be easily replicated in their previous lives. It is quite possible that demobilization for Clarice was both a welcome return to family life and a sad parting from an organization that had recognized and developed her organisational talents.

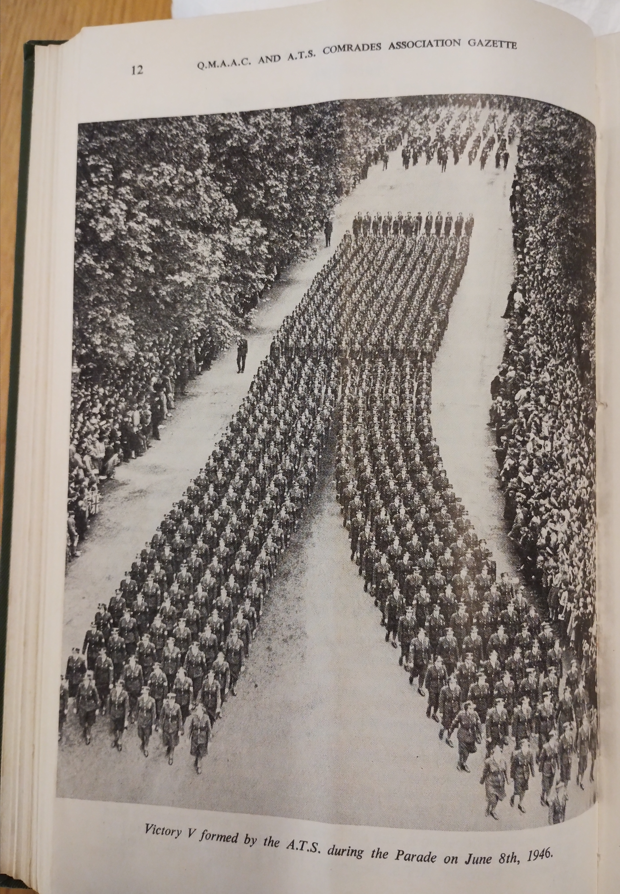

Image 10: A.T.S. members during the London Victory Celebrations of 8 June 1946

From the Q.M.A.A.C and A.T.S. Comrades Association Gazette, July-August 1946

National Army Museum

Read Part 5 – Click HERE

References/Sources

[1] London Gazette, 26 March 1940.

[2] North Wilts Herald, 18 October 1940, Liverpool Echo, 22 April 1941, Bolton Evening News, 18 August 1942, Nottingham Journal, 5 July 1946.

[3] Noakes, pp.83-84.

[4] https://collection.nam.ac.uk/detail.php?acc=1994-07-296-15 accessed 5.1.2024.

[5] Noakes, p.125 and 131.

[6] Ibid, p.102.

[7] Ibid p.107.

[8] Ibid, p.108.

[9] Ibid, p.109.

[10] Ibid, p.106.

[11] Ibid, p.106.

[12] North Wilts Herald, 18 October 1940.

[13] North Wilts Herald, 7 March 1941.

[14] Bolton Evening News, 13 March 1941.

[15] North Wilts Herald, 10 April 1941.

[16] Noakes, pp.109-116.

[17] Ibid, pp.110-116.

[18] For more about the poster see https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/war-glamour accessed 8.2.2025.

[19] Liverpool Echo, 22 April 1941.

[20] Liverpool Echo, 2 September 1941.

[21] Runcorn Weekly News, 14 November 1941.

[22] Bolton Evening News, 18 August 1942.

[23] https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/the-nation-at-a-standstill-shutdown-in-the-second-world-war#:~:text=The%20blackout%20caused%20widespread%20inconvenience,same%20month%20the%20previous%20year accessed 5.1.2025, and Bolton Evening News, 20 December 1941.

[24] Bolton Evening News, 29 December 1942.

[25] https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205497273 accessed 14.2.2025. In total there are 27 photographs of these women.

[26] Lancashire Daily Post, 11 March 1943.

[27] Lancashire Evening Post, 12 March 1943.

[28] Noakes, p.123.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid, p.124.

[31] Chester Chronicle, 31 July 1943.

[32] Nottingham Journal, 5 July 1946.