Transnational interactions between England and the Netherlands in the late 19th Century were both pluriform and numerous. In the game of cricket, a number of individuals based in England played an important role in inspiring cricket across the Netherlands. But towards the end of the 19th Century, the focus on English cricketing superiority led to the development of an obsession with the constructed idea of the ‘English’. It was an obsession which diverted attention from the domestic game and was an important factor in the cricket’s marginalisation in the Netherlands.

-

A Netherland’s XI v Marylebone Cricket Club, The Hague, August 1902.

Source- Nationaal Archief, Den Haag, 2.19.125 KNCB Archive, Document Folder 1085

Anglo-centric work is a continued problem in sport history. However, as Stokvis and Van Bottenburg have shown, English influences in the formation of Dutch clubs and associations were important. In 1880, one Dutch writer noted that an ‘Anglomania’ had swept through continental Europe and sport was part of this. To play sport was to take part in a fashionable activity, which represented a dominant and successful culture. While parts of Dutch society disliked this new fashion, it seemed to resonate with many young men who were earmarked as future business leaders or traders.

But the sporting trend was not new in the 1880s. Recent research from Luitzen and Zonnenveld has shown that cricket was played at the Protestant Noorthey School, outside The Hague, from around 1845 onwards. Stimulated by a ‘native speaker’ of English, students from the school would go on to play an important part in establishing sporting clubs across the Netherlands. In the mid-nineteenth century, cricket clubs came and went. Some had links to British culture. Men, such as British-born Heldson Rix, travelled to Noorthey as an English teacher for work in 1878, not only encouraging sport for students, but later establishing a club of his own. Young boys from the Netherlands, like Pim Mulier, went to English schools where they played cricket. Such youngsters would go on to play important roles in sporting clubs across the Netherlands when they returned. Diffusion, if that is the correct word, did not happen from one place, but through a variety of different cultural exchanges of varying intensities and at different times.

In 1881, Uxbridge Cricket Club became the first English team to play a match in the Netherlands, a match that F.W. Hetherington, a shipping agent for the Holland-America Line, helped to arrange. By late 1882, a number of cricket clubs had appeared, not just in large cities in the west, but also in the east and north of the Netherlands. In September 1883, 60 cricketers from around the country gathered in Utrecht and the Nederlandsche Cricket Bond (Dutch Cricket Association, NCB) was formed, initially comprised of 14 different clubs. The regulations to be used were those of the famous Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC).

Numerous clubs existed outside of the NCB and by 1886 as one Dutch writer said, ‘clubs rise like mushrooms in the ground’. Unfortunately, many disappeared as quickly and there was a great turnover of membership in the NCB. Sometimes the use of English was a problem. Two enterprising cricketers suggested a list of Dutch replacements for ‘wickets’, ‘no ball’ and ‘byes’. However, the use of English and the concept of England was beginning to form a discursive ideal. As a letter noted in 1885: ‘England must remain our ideal […] in all things, which concern cricket, we cannot have a better example than the English and, as far as possible, we must follow their example.’ The idea of ‘England’ provided both an ideal and a norm, something to measure Dutch cricket against, and could be used as simple way to assert authority.

-

A suggestion for some English -Dutch cricket translations

Source- Nederlandsche Sport, 08:03:1884 [no page number]

Links to the MCC, its rules and Englishness, seemed to suggest that the NCB was serious about cricket – it seemed to provide a sense of cultural legitimacy. However, as some in the Netherlands pointed out, the structures of the NCB were entirely different to how the game was governed in England. By 1886, critics were saying that the association was failing, it had not created enough interest in cricket, and it was losing its young players.

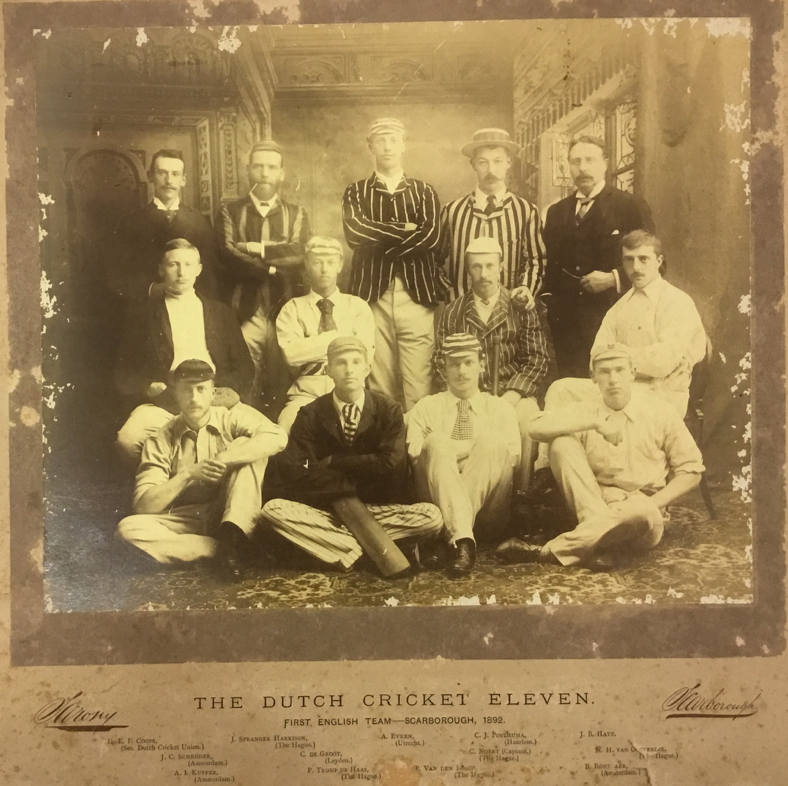

While arguments continued, individuals developed transnational networks. From 1884, English clubs toured the Netherlands regularly. F.W. Hetherington was only one of a series of those who helped organised tours. Heldson Rix’s contact R.B. Webber organised tours and through him Arthur Bentley came to the Netherlands as a professional coach in 1889 to help improve the quality of play. Scottish based J.B. Hatt helped arrange tours by British cricketers to the Netherlands and, in 1892, helped bring a Dutch XI to play several games in Yorkshire; the first time that a Dutch team had toured in England.

-

The first Dutch cricket tourists- The Dutch Touring Team to Scarborough of 1892.

Source- Nationaal Archief, Den Haag, 2.19.125 KNCB Archive, Document Folder 1102

In 1894, with the support of noted cricket enthusiasts, C.W. Alcock and Lord Sheffield, a Dutch XI toured London, playing at the famous Lord’s cricket ground. A few Dutch individuals tried to make their name in English cricket, one, Carst Posthuma, played five games with W.G. Grace’s London Cricket Club in 1903. These agents of cultural exchange provided access to new English and Dutch networks. They helped developed transnational networks of internationally minded young Dutch men, and sportingly minded English individuals.

Weekly reports in Nederlandsche Sport, and later De Athleet, provided match reports and stories about the heroes of English cricket. Such stories helped to reinforce the discursive power of the ‘English’ within the Dutch cricket world. Early tours by English sides, where clubs from Haarlem, Amsterdam and The Hague were easily beaten, reinforced this idea of superiority.

Differences between the sport in England and the Netherlands were frequently noted with disappointment. In 1884, after translating a review on the history of English cricket, Frans Netcher, the first president of the NCB, sadly asked why there were no influential patrons in the Netherlands? Despite being linked to those of good social standing, the Association was frequently searching for money. For its tours to England in 1892, it had to rely on donations from a wealthy club and financial benefactors. But matches against English clubs formed the highlight of the cricketing summer calendar. They were a chance to measure oneself against the English, to wear the right clothing, to behave properly, to use a good pitch and to form influential English contacts. It was a chance to practice ‘Anglomania’, to be part of a craze.

-

A group photo of the Gentlemen of Worcestershire and the ‘All Holland’ team in Heemstede, 1895.

Source- Nationaal Archief, Den Haag, 2.19.125 KNCB Archive, Document Folder 1105

And it seemed the practice had paid off. In 1894, a Dutch representative team appeared at Lords as part of a tour which also saw them play against top club sides. But this English connection masked problems. In 1894, a summary of the cricket season cast a downbeat note. Despite the tour, Dutch cricket had contracted; there were too few matches, too few grounds, and many good players had left the game. In 1897, Former president of both Dutch Cricket and Football Associations, Pim Mulier, wrote a book called Cricket. In it, he noted that 1889 was one of the last years of growth in Dutch cricket. By the end of the 1894, there were, he said, only 310 individuals who were members of the NCB. Cricket continued but did not become a mass sport.

-

The second Netherlands XI team to tour England, 1894.

Source- Nationaal Archief, Den Haag, 2.19.125 KNCB Archive, Document Folder 1104

As Van Bottenburg notes, this was, at least in part, a consequence of social exclusivity and a failure to find new members. Youthful teams grew up, found jobs, families and new lives, which had no space for cricket. They were not replaced, partly, because many clubs had restrictions on who could join. This exclusivity, in part fuelled by the English ideal of the ‘gentleman amateur’, was a factor in the marginalisation of the game.

A lack of space to play was also a fundamental problem. Playing English clubs became the most important thing for leaders in the NCB, rather than expanding the domestic game. While the game of football increasingly found spaces to play, cricket struggled. Often municipalities would not allow people to play on public land, as the risk of the ball injuring a passer-by was a concern. More often, the quality of the ground was too poor to allow ‘proper’ cricket to take place.

-

A photo from the Dutch cricket tour to England in 1901- Practice in the nets at Crystal Palace.

Source- Nationaal Archief, Den Haag, 2.19.125 KNCB Archive, Document Folder 1106

While links to England may have helped expand the game initially they also constructed a discursive ideal. This acted as a way to measure improvement and develop legitimacy; however, it became an impediment to the spread of organised cricket in the Netherlands. The diffusion of cricket to and through the Netherlands did not happen in a linear path or from a single point. It was complex. Instead of English interaction encouraging the growth of the game, to be like ‘the English’ became an obsession. It was an obsession which saw the game contract and become marginalised in Dutch society.

Article © Nick Piercey

![A suggestion for some English -Dutch cricket translations Source- Nederlandsche Sport, 08:03:1884 [no page number]](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/A-suggestion-for-some-English-Dutch-cricket-translations-Source-Nederlandsche-Sport-08031884-no-page-number.png)

![“And then we were boycotted” <br> New discoveries about the birth of women’s football in Italy [1933] <br> Part 4](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/PP-banner-maker-440x264.jpg)