According to a file stored in the Jewish Municipal Cult Archive of Vienna, Alfred König was born on 2 October 1913, son of Jakob a tradesman born in Istanbul in 1882 who after World War I returned to Turkey, but was later forced to escape because of the introduction of anti-Semitist laws in the late 1920s. Alfred was only registered as resident in Vienna for the year 1932 but in 1930 he had already debuted in athletics for Hakoah, the most famous Jewish club of Vienna.

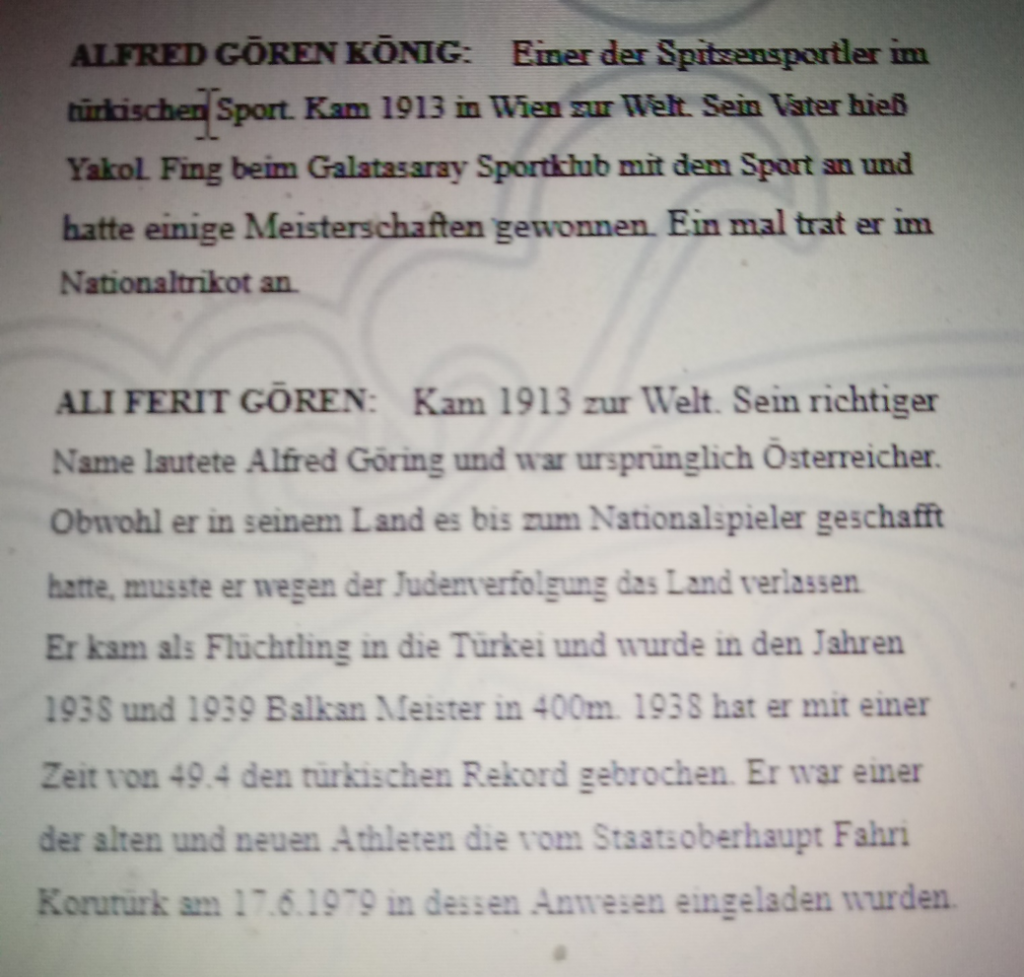

- Excerpts of Turkish sport encyclopaedia (in German language) in which two sketches “Gören König” and “Gören Göring” were still talking about two athletes not understanding yet he was really one athlete

He ran in the 100, 200 and 400 meters, which wasn’t unheard of in Austria. One of his main opponents, Felix Rinner, who later became part of the SS, did the same. Junior champion of Austria in the 400 metres in 1932, König remained in the Austrian elite until the Anschluss, and as a result Hakoah became extremely competitive in relay races because he was performing and crucial leg in all the distances. At that time, Austrian championships scheduled not only the usual Olympic relays, but often 4 or 5 titles were also at stake. König’s main troubles began in 1934, with the spread of Fascism to Austria, but not for his political views. According to the historian Neugebauer, Austrian fascism consolidated its power with dozens of restrictive laws, especially affecting citizenship. In this field, the legislation tried to block Nazi influence and to hit Austrians who had fled to Germany, became Nazis and, eventually, returned to Austria as spies. The restrictions pivoted on two elements: taxation hitting the ownership of goods, insurance and income, the discretion of civil authorities to allow citizenship according to official alignment with the fascist regime, often after police investigations.

- 4 x 400 Hakoah 1932 that deprived in 1936 of the victory left to right – Metzl, Deutscher, König, Klein

The updating of citizenship laws affected the requirements of Austrian athletes to take part in championships, set national records and represent Austria. In 1935 following a new bill, König became a Turkish national once again and as a result could no long participate in Austrian championships. In April 1936, the Austrian federation took back two national titles from Hakoah which König had won in 1932 because of the issue of his nationality. The Olympics of Berlin in the summer of 1936 represented a crucial moment. König seemed to have resolved his issues and won his only individual senior Austrian title in the 400 metres thereby qualifying for the Olympic selection. Hakoah boycotted Berlin and three women swimmers refused selection and were disqualified. König was determined to take part in the Olympics and on 29 July, his ties with Hakoah were cut.

In Berlin, König was eliminated in the qualifications for the 200 and 400 metres. In September 1936, König was again accepted by Hakoah. However, already by the first months of 1937 his citizenship status was again up for discussion. The Patriotic Sporting Front, the fascist umbrella organization, knew his situation: for Austria, he had refused the Olympic boycott and was assured that the “formalities” would be resolved imminently. But König was stopped in the stadium of Klagenfurt just before the start of the 400 meters in the national championships. The sporting body played a double game which favored Nazism so most probably König was a victim of anti-Semitist clerks. The Patriotic Sporting Front was increasingly devoid of authority. At the moment of the Anschluss, the formalities had still to be resolved but the priority for König was to escape Nazi oppression.

- König establishing record 22.0 for 200 metres

- Excerpts of article in Sport Tagblatt (28 July 1937) reporting that König has been stopped from starting in Klagenfurt for failure in formalities “formfehler”

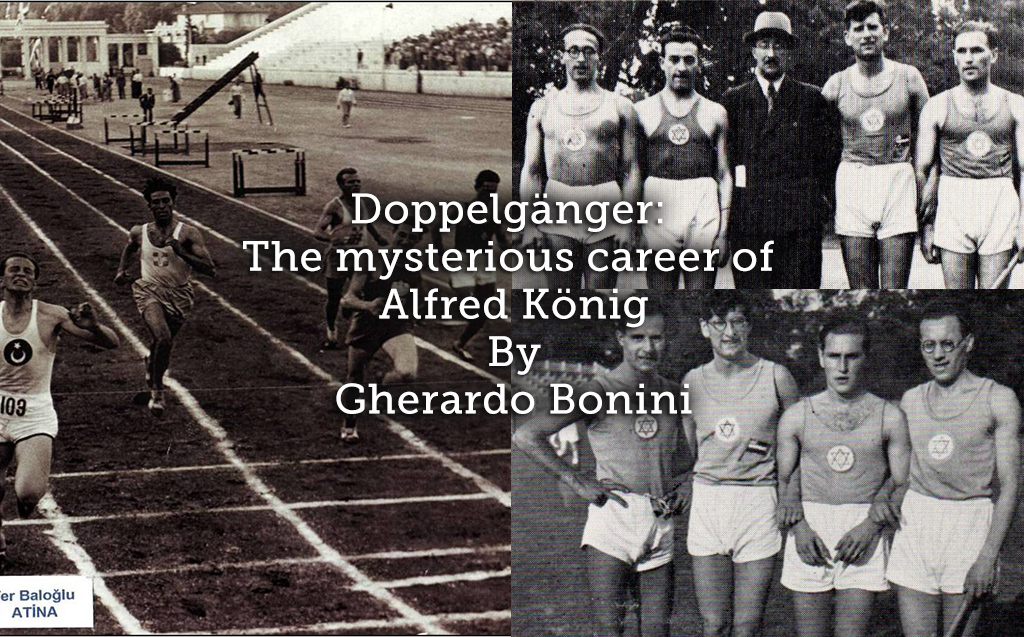

Six months after the Anschluss, in Athens the Turkish Ali Ferit Gören won the 400 metres and was placed 3rd in the 200 metres in the Balkan Games. Several photos immortalized the athletic events but very few experts recognized that Ali Ferit Gören was in fact Alfred König. How was this possible? The most eminent sporting journalists of the time were unable to provide a definitive answer to the question. König declared himself to being Alfred Göring. He probably changed his name, as “König” was easily recognized as a Jewish surname, moreover the number 2 of Nazi Germany was named Göring so the customs officials took him at face value. How did König manage his (possible) documentation as a Turkish subject? Did he keep some of his old passports? Apparently not, because that documentation referred to König. Did he declare that he was a citizen of Austria or that he was from Germany? In any case, the situation was difficult because Turkey pursued an anti-Semitist policy, by not allowing shelter to Czechoslovakian, Austrian, Polish subjects who were escaping from Nazi aggressions in Europe. However, if König, notwithstanding his best efforts was unable to solve the formalities with the last Austrian government, he succeeded in obtaining complete Turkish citizenship status. Probably, he spoke already Turkish, because state and popular feelings despised non-Turkish speakers.

- The winning relay 4 x 400 in 1937 Austrian championship left to right – Präger, Kaiser, coach Bierbrauer, Deutscher, König

He won again the Balkan Games in 1939 in the 400 meters and his national record of 49.0 remained unsurpassed until 1955. In Austria, König/Gören ran under 49.0 only once. Therefore, he did his best, remaining until 1944 in the elite of Turkish athletics, after which he became successful trainer. The respect surrounding his name, because at that time Turkey was not used to winning many international honours and König with two victories in the Balkan Games became part the elite of Turkish athletes. Over the years, it was inevitable that his past would catch up with him and cause confusion. In an Encyclopedia of the late 1960s, two sketches referred to Alfred König and Alfred Göring as two separate athletes. Later on, another updated Encyclopedia presented one sketch for Ali Ferit Gören as also Alfred König, champion of Austria in the 400 metres in 1936.

-

Balkan Games, König is already Gören and competing for Turkey and is the first from right

http://www.atletin.org/izatletizm/goren%20ali%20ferit.htm

In 1979, the President of Turkey organized a Presidential gala in which all outstanding Turks who had brought honour to their countries, including sportsmen were invited. The question which remains is how Gören who lived a quiet life without discrimination was able to leave behind all his Jewish roots and assimilate another persona. We don’t know the response to this nor is it the only mystery surrounding Alfred König and his doppelgänger Ali Ferit Gören.

![Playing Football with the Chorus Girls: <br>Vaudeville Women’s Football in Naples [1931]](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/PP-banner-maker-440x264.jpg)