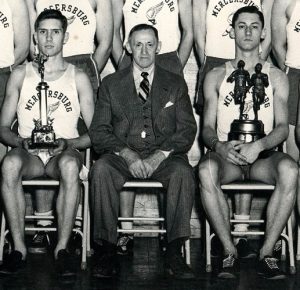

Mike Murphy was the most respected coach in America, the ‘dean of coaches’ some called him. So when Murphy offered the name of Jimmy Curran to William Mann Irvine, headmaster at Mercersburg Academy, an elite prep school in southern Pennsylvania, Irvine listened. Jimmy Curran, Murphy would have told him, was an accomplished athlete in his own right, and had ably passed on his skills to students for three years at the University of Pennsylvania. Irvine needed no more persuading. Murphy’s talent spotting of athletes and coaches was legendary. Irvine offered Jimmy the role of Head Coach at the Academy.

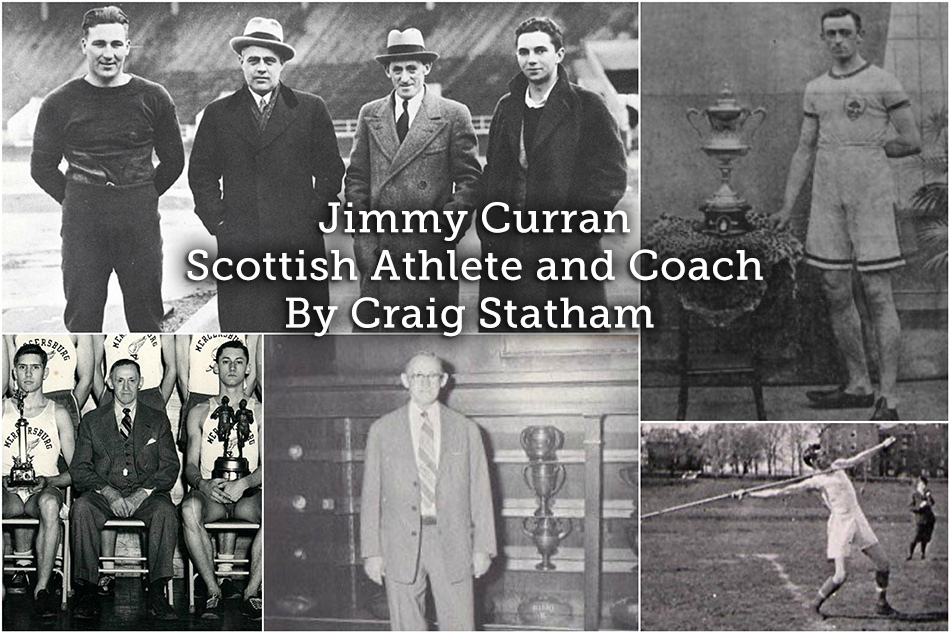

- Jimmy at Franklin Field, Philadelphia, c1920

Jimmy was a diminutive man, stretching 5’4” on a good day. His prominent ears, jutting lower jaw, and ski slope of a nose, were greater than the sum of their parts, and in his early years his black hair was swept back revealing a dashingly handsome young man. In later years, as his face dropped a tad, reporters began to liken him to the Irish actor Barry Fitzgerald. When he died, in 1963, he had, much to the amusement of his students, retained his thick Scottish accent.

When Jimmy took up the role at Mercersburg, in 1910, he had already filled his 30 years with a good deal of adventure and sporting achievement. He had fought his way through the Second Boer War, where he discovered and trained a fellow Scottish athlete called Wyndham Halswelle. On returning home he continued to train Halswelle, readying him for a series if sporting meets which would culminate at the 1908 London Olympics when, in highly controversial circumstances, he won the 400m final running against no opposition.

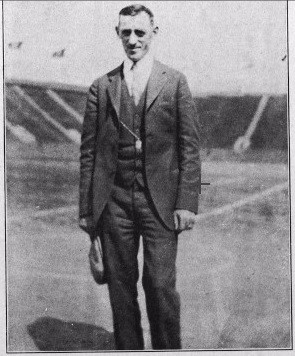

- Jimmy with his trophy after winning the Border Mile Championship in Hawick, 1903

Jimmy continued his own running exploits in the Scottish Borders, first as an amateur when he won the illustrious Border Mile Championship at Hawick, then in the professional ranks when competing against men of the stature of John McGough, George Tincler, Elbridge Eastman, and Bill Struth (the latter soon to become Glasgow Rangers’ most famous manager). His successes led John James Miller of the Aberdeen People’s Journal, in 1907, noting that he was ‘the best all-round, over any distance man at present on the track’. He was not alone in this view.

But Jimmy’s talents offered so much more than the £10 plus gambling returns on offer at Scottish events. The great Alfie Shrubb, for example, was winning thousands of dollars. And so Jimmy, newly-married with a three-month-old daughter, emigrated.

After a brief stint as a puddler’s assistant at Reading Iron Works, Mike Murphy offered him a job as a rubber (masseuse) at the University of Pennsylvania, and over the next three years he worked his way up to assistant coach of the cross country and freshman track teams. By the time Murphy put him forward to take over the Head Coach role at Mercersburg, Jimmy had built up a wealth of coaching knowledge, and was an accomplished in-demand runner competing against the very best on the east coast. Apart from an incredibly successful jaunt back across the Atlantic in 1913, when he won virtually every event he took part in, his athletics career slowed after he took up his new role.

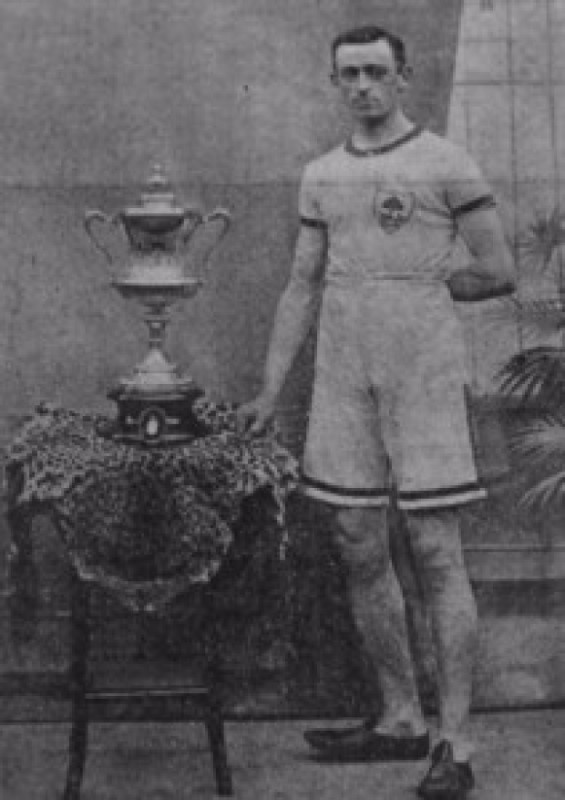

- Jimmy showing his all-round ability, c1914

Mercersburg was no ordinary school. Its students were the sons of presidents, bankers, and industrialists. The American elite. It also provided scholarships for top athletes, making it an athletics powerhouse. And Jimmy’s first real success came about due to the scholarship programme.

Ted Meredith was brought to see Jimmy in 1910, a talented but raw 19 year old. Two years later the newspapers would be lauding him as ‘the schoolboy wonder’, the athlete who rose from obscurity and walked away from the 1912 Stockholm Olympics with two gold medals. After an interruption caused by the First World War, Jimmy’s athletes returned to the Olympic arena in 1920. Allen Woodring, travelling only as an alternate, was given a chance and stormed to gold in the 200m. Bill Carr would be his fourth gold medal athlete, winning two events at the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics, and Charles Moore his fifth, with a gold in the 400m hurdles at Helsinki Games in 1952.

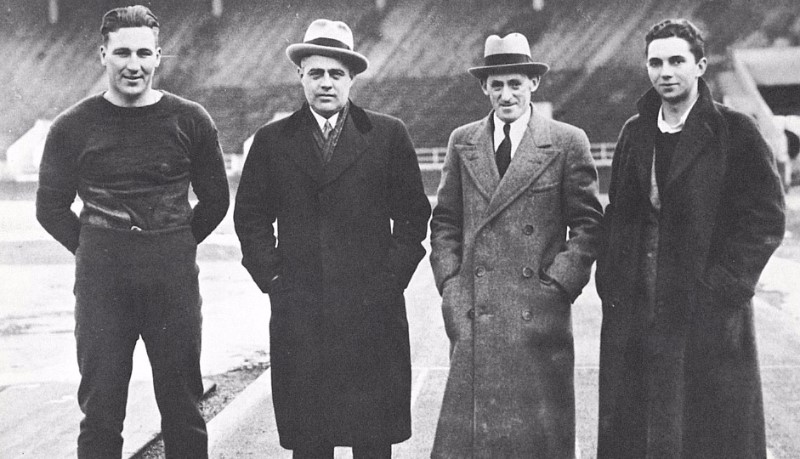

- Jimmy with three Olympians – Barney Berlinger, Ted Meredith, and Bill Carr

For many years afterwards his athletes would covet Olympic glory – Hank Thresher’s chance was ended by injury, and Rolando Cruz attended three Games as a pole vaulter – but none would deliver.

But Jimmy’s legacy did not depend solely on the medals – five golds and a wealth of silvers and bronzes – won by his athletes. He lived on in the memory of athletes because of the man he was. Every student had a different story to tell of Jimmy. When being honoured at the Penn Relays for having attended 50 years in a row he forgot his pass. He turned to the guard and said ‘I forgot my badge, but I am Jimmy Curran and I am being honoured today’. ‘And I, by God’ came the reply ‘am the Pope’. On returning to the Academy he regaled students with his version of what followed. Realising the guard wasn’t too bright he said, ‘I just turned around and walked in backwards and he thought I was coming out’. He left an impression with all he met. Forty years after training a young athlete called Jimmy Stewart, the former high jumper, now world-famous actor, sent a telegram of condolence to the family of the man who, 50 years after Mike Murphy had secured him the Head Coach role at Mercersburg, he died bearing Murphy’s former mantle – ‘dean of coaches’.

- Jimmy with silverware in the early 1950s

- Jimmy in his later years, c1960

Article © Craig Statham