To read the earlier articles in this series by Lisa please click on the links below

Part 1 – Sports Migration during National Socialism: Reasons and Research on the Emigration of Jewish Athletes from Germany after 1933 – Click HERE to read

Part 2 – Daniel Prenn ~ Emigrations in the Life of an International Tennis Star: From Germany’s Celebrated Number One to Eviction Within a Year – Click HERE to read

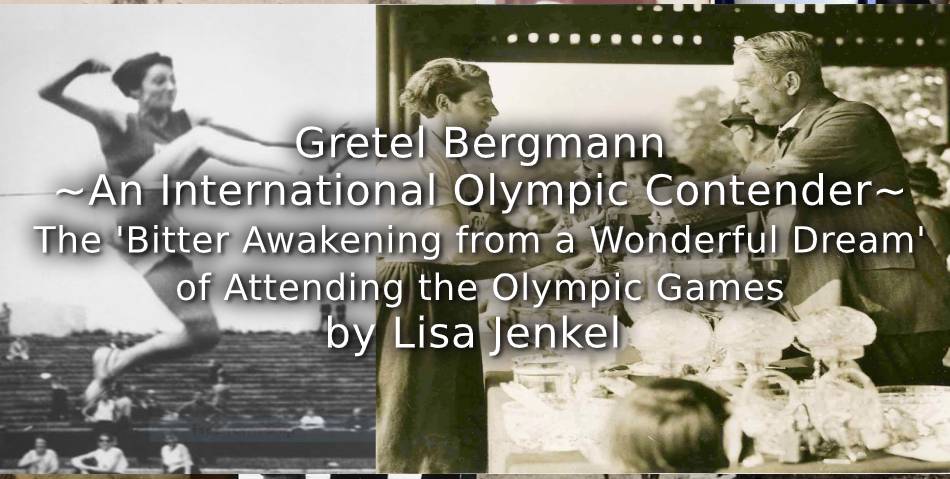

With the segregation of German sport in 1933, Gretel Bergmann became one of many Jewish athletes excluded from their former clubs. Yet for her sport was more than a leisure activity, blessed with an aptitude for high jump she had the talent and strong desire to compete at the Olympic Games – a desire repeatedly blocked by the National Socialists.

Margarethe Minnie Bergmann, called Gretel by her relatives, was born into a Jewish family in the small town Laupheim, Baden-Wuerttemberg, on the 12th of April 1914. An exceptionally active and sportive child, Gretel made her first organized attempts on sports at the Laupheim Gymnastics Club, which she joined before the age of eight. At the age of ten she had found her future calling:

“I had already won several competitions convincingly and knew which direction I wanted to take in life. […] I announced at the time that I wanted to become a coach or physical education teacher.” [1]

In 1930, Gretel was sent to Ulm to visit the high school there and joined the local Ulm Football Club 1894, which had an athletics section too. Here, she had better facilities and overall better possibilities to develop her talents than in her small Laupheim club. In her memoires she remembers:

“Joining a new club is like starting an exciting new love affair. I was welcomed with open arms and from day one felt like I belonged.”

Even though Gretel participated in several disciplines, high jump was her most successful one. In 1931, she was listed at 4th place in the national high jump ranking after winning the South German championship, which she was able to repeat the following year. With these accomplishments she became a promising contender for the Olympic team and was selected for specialised trainings camps. Another achievement was her admission to the College for Physical Education in Berlin, where she wanted to be trained for her envisioned career as a physical education instructor.

The developments following January 1933 prevented Gretel’s career – both sportive and occupational – to strive further. Not only was she informed to ‘postpone’ her studies in Berlin, but she was also excluded from her beloved Ulm club:

“My world collapsed: […] Forgotten the beautiful hours that we had spent together, forgotten the medals I had won for the club, forgotten the camaraderie.”

Gretel Bergmann had become banished from her club and competitive sport in Germany.

Gretel became a promising contender for the Olympic Games 1936

In her memoirs Gretel notes that emigration became an increasingly important topic among the Jewish community, though linked to many difficulties, considerations and hesitancy. For Gretel, the topic often demonstrated how much solidarity was lacking for Jewish refugees worldwide:

“Soon the word ‘emigration ’became an integral part of our vocabulary – so easy to say but so difficult to achieve. As bad as the thought of separating yourself from everything you had ever known was, there was still a much harder nut to crack: where should you go? Going to another country was a bureaucratic nightmare. […] Nobody expected benevolent treatment from the Nazi government, but the immigration authorities in other countries had no understanding of the urgency of our situation either.”

Despite the situation in Germany, many governments of destination countries were quite repellent towards immigrants. This was also the case in the United Kingdom, which tried to establish itself as country for trans-migration only.

Her father eventually had the idea for the young sportswoman to study in England. Due to his business contacts, the family had already established connections in the country. Another factor for Gretel was the wish to pursue her intended career as a physical education teacher. She initially hoped to study at a specialised college in England. Such a migration for study reasons was an endeavour quite widespread among German Jews in the period. Student immigrants were among the few foreigners welcomed, as they not yet posed any competition at the domestic labour market. Unfortunately, Gretel and her father did not find a school in London that corresponded to her interest, so she decided to enrol in an English program at the London Polytechnic to learn the language first.

Simultaneously, the athlete developed another aim she wanted to achieve abroad:

“slowly but steadily, the thought formed to somehow make it into the British Olympic team. I knew that only nationals could represent their country at the Olympic Games, but I told myself that it was not an insurmountable obstacle. In my youthful optimism, I believed that rules were there to be broken. If I somehow managed to become an enrichment for the British team, surely some tricks could be found to make my dream come true.”

Gretel not only perceived the UK as an opportunity to continue practicing sport competitively and for education, but also as a passageway onto the stage of the Olympic Games.

Owing to her studies at the London Polytechnic, in early 1934, she became a member of the school’s sport club for women, the Polytechnic Ladies Athletic Club. The ‘Polytechnic Ladies’ belonged to the Women’s Amateur Athletics Association. Very differently from her former clubs, where she often describes herself as one of few women, Gretel now competed exclusively among female students and successfully so:

“Once the athletics season started, I was disappointed to find that none of my contenders were a competition for me […] I won every competition I competed in without having to really exert myself.”

Despite these sportive successes, however, her descriptions of the time in London are predominantly negative. One reason was her unsatisfying knowledge of the language.

Gretel recalls that she was often unable to comprehend conversations, felt excluded due to her insufficient language skills and her accent, which she was uncomfortable with. This also had an impact on her position in the British sports world, where, due to her accent, she was easily identified as a foreigner and felt alienated:

“Since I was the only competitor from the ‘continent’, I didn’t know what the others thought of me. They kept their distance, and I, too, bothered by my accent, stayed away from them. I just did what I had to do and measured myself with them, jump by jump.”

Most of Gretel’s descriptions concerning her sportive environment correspond to this feeling of alienation and lack of belonging. She repeatedly describes the unwelcoming attitudes she encountered, which made her feel unsolicited and aggravated her integration:

“it really hurt that no one ever invited me to their home. In Laupheim we always tried to welcome strangers […]. Here in London I thought I had left discrimination behind, but maybe I had to face it again in good old England because I was German? These and similar experiences, I made later, did not exactly make the English grow dear to me.”

Her description speaks to a deeper phenomenon shared by many Jewish immigrants at the time. While they had been excluded from their societal environment in Germany due to their Jewish background and their Germanness had been denied based on the Nazi ideology, in the UK Jewish migrants faced aversion based on their German origin. This became evident in everyday encounters, employment or lack thereof and the educational and sportive environment, as in this case.

On the 30th of June 1934, Gretel competed at the British Women Amateur Athletics championship. This was her most important tournament yet, not only because she was able to compete for the title of British champion in the high jump, but because she perceived the competition as her chance to become an Olympic contender for the UK. Ultimately, Gretel won the high jump, beating the previous consecutive winner Miss Milne and, as a foreigner, becoming the British champion.

While she hoped to be on the right way towards joining the British Olympic team, it turned out quite contrarily. In her memoirs she retrospectively described the initial feeling after her success as triumphant:

“I had achieved what I had set out to do. Now, my name was known in the British sports world, and with this championship I had proven that I was a world-class athlete. It was time to announce that I wanted a place in the British Olympic team […] Then I remembered that despite all the censorship it would somehow reach Germany that a German-Jewish girl had won the British championship so convincingly. What about the Nazis’ ideology of the inferiority of Jews? I had really refuted that.”

Gretel receiving the Cup for her victory in the high jump at the British

Women Amateur Athletics championship 1934

Photo “German Girl’s Success” Source: RSP/7/c/40, University of Westminster Archive, London, United Kingdom

Image reproduced courtesy of the University of Westminster Archive

Indeed, the National Socialists had taken notice of Gretel’s achievements, even prior to her success at the championships. And as described by herself, “fate” soon ruined her enthusiasm when her father informed her that the Nazis had ordered her return to Germany. She was expected to compete in try-outs for the 1936 German Olympic team. Under threat to her family and even the Jewish sports federation she was forced to return.

Hereby, the Nazis pursued a policy of deception towards the international public. The regime had been strongly criticised for their treatment of Jews and the exclusion of Jewish members from sports clubs in Germany. The outrage was so severe that some countries’ Olympic committees considered boycotting the games and the International Olympic Committee contemplated a withdrawal of the games. To prevent this, the National Socialist officials decided to invite Jewish athletes for training sessions and ‘officially’ gave them a chance to qualify for the team.

In order to be capable of training for the try-outs, Gretel moved to Stuttgart and joined a Jewish club in the city. Moreover, she was finally able to start her desired study as physical education teacher at a school in Stuttgart that still accepted Jewish students. And even though she was forced to leave the institution in May 1936, Gretel was able to finish her education with a degree.

In her new club, the training conditions were imperfect and she did not receive adequate training. This was a challenge all the athletes invited to separate Jewish try-outs had to face. They had less coaching and had to endure more mental strain. Gretel was able to withstand and got invited to general try-outs as the only Jewish candidate – she became the ‘Jewish hope’ for the Olympic Games, as she has also titled her memoirs.

In June of 1936, mere weeks before the Games, the sportswoman achieved a significant success by winning the high jump at the Wuerttemberg Championships, equalling the German record of 1,60m. With this achievement the stage was set for her to compete at the Olympic Games.

However, waiting until a boycott of foreign teams was averted, the Nazi sport officials informed Gretel a month before the Games that she had not been selected to represent Germany due to her alleged “instable performance”. In public this was not communicated at all and her teammates were told that Gretel had injured herself.

“It is difficult to properly assess my reaction to this rapid and sadistic end of a two-year alternation of feelings between highs and lows, expectations and disappointments, euphoria and broken hopes. It was a bitter awakening from the wonderful dream I had, perhaps out of foolishness, been dreaming. I had never experienced so much anger, so much fury before, and yet suddenly an enormous relief overcame me. Gone were the worries of what would have happened to me if I won, if I lost.”

After this repeated maltreatment due to her Jewish background, Gretel decided to leave Germany once and for all and emigrated again, this time to the United States.

The migration processes and her first months in the new country proved difficult. Despite these hardships, Gretel remained a passionate athlete and was able to win the American championship in high jump in 1937 and the following year; 1938 in the shot put as well. Having achieved these successes, her dream of attending the Olympics returned – this time she hoped to be part of the American team for the 1940 Games. However, the outbreak of the war and with it the National Socialists, once again, interfered with her plans.

In the US, Gretel married Bruno Lambert, a long jumper, whom she had met during one of the separate Jewish Olympic try-outs. After the war, the pair had two sons. And in 1939, Gretel’s family finally arrived in the United States too – following a strenuous escape that prompted Gretel to admonish in her memoires:

“When the German Jews realized that the political situation was not going to change anytime soon, they tried, no matter what, to get out of Germany. However, it did not take long before we realized that nobody wanted us. […] The rest of the world kept the door to freedom well closed. The applications for immigration were so numerous that it became a kind of lottery who was allowed to go where and when. The higher the number on the papers, the longer you had to wait. Apart from the psychological stress that such an uncertain future imposes on the individual, it was bitter to experience that rules and regulations, bureaucracy and files were more important than the fate of people. […] The decision to leave home, maybe forever, is painful even under the most optimal conditions.”

Margaret Bergmann Lambert at 95 – living in the United States

After the end of National Socialism, reminiscence or rectifications from Germany or the National Olympic Committee remained unredeemed. Only in 1999, Gretel was awarded a price for her sportive achievements in Germany and attended an event in which a stadium in her hometown was renamed to remind of her story: Gretel-Bergmann-Stadion.

Gretel Bergmann died in New York on the 25th of July 2017.

Article © of Lisa Jenkel

Read Part 4 – ‘Martha Jacob ~First Female Foreign Coach in UK ~ The Odyssey of an Uprooted Athlete and Physical Education Teacher through Europe’ – Click HERE to read

References

[1] This and all further quotes translated from: Gretel Bergmann, Ich war die große jüdische Hoffnung: Erinnerungen einer außergewöhnlichen Sportlerin (Karlsruhe: Der Kleine Buch Verlag, 2003);

The book has also been published in English: Margaret Bergmann Lambert, By Leaps and Bounds (Washington: United States Holocaust Museum – Holocaust Survivors Memoirs Project, 2005).