This year ( 2023), will mark 75 years since the ‘Colour Bar’ in British boxing was abolished, finally allowing boxers from black and mixed race backgrounds to be on an equal footing with their white counterparts enabling them to challenge for British professional titles.

The colour bar was introduced in Britain in 1911 due to the concerns of public reaction to the possibility of a black man defeating a white man in the ring and according to Professor Martin Johnes, tweeting in 2020,

What started as an unofficial ban was formalised in the inter war years by The British Boxing Board of Control (BBBC).

It operated originally through the sport’s self proclaimed governing body, the National Sporting Club (formed in 1891 as a private club with the Earl of Lonsdale as its first President), but from 1929 the BBBC took over reinforcing the fact that non-white fighters could only compete for the British Empire Championships which had to take place outside the British Isles.

Neil Carter in ‘British Boxing’s Colour Bar’ in 2011 says that

those fears were crystalized through the proposed heavyweight fight in October 1911 between the black American Champion of the World Jack Johnson and the British contender, Bombardier Billy Wells.

Johnson had beaten the white boxer Jim Jefferies, (labelled ‘The Great White Hope) in Reno in 1910 and following his victory there had been race riots across America and the film of the fight was banned in cinemas.

Jack Johnson- Heavyweight Champion of the World

Johnson was widely hated in the US as he flouted his status as champion, contradictory to the perceived standing of a black man at the time, which included several relationships with white women. The British Home Secretary Winston Churchill, was put under enormous pressure to ban the fight and eventually declared the fight ‘illegal’ as further fears were raised that a Johnson victory might have consequences for the Empire.

The Wells-Johnson case came to act as a precedent for the Home Office and was subsequently used in the years to come to ban all high profile fights between white and black boxers and the imposition of the colour bar, meant that many black or mixed race boxers were denied the chance to fight for professional titles in the British Isles.

One such boxer was Cuthbert Taylor from Merthyr Tydfil in South Wales, once described as, ‘the best in Europe’, who was of mixed race and as a result was judged to be, ‘not white enough to be British’, by the BBBC and was thus prevented from ever challenging for a professional British title.

Writing on the Merthyr history website ‘The Melting Pot’ in 2019, Lawrence Davies noted that,

Along with Pontypridd, Merthyr Tydfil could rightly claim to be one of the foremost hubs of Welsh Boxing Historyand when the railway was extended to Merthyr in 1840, local people celebrated with a boxing match

Welsh historian Gareth Williams added that, ‘

the adoption of boxing as a sport in towns like Merthyr reinforced the fact that life in these industrial towns was short and that boxing was still a means to rise above the poverty of everyday life

In fact a walk around Merthyr today shows how important the sport is to the town:

Where else on the planet can you find no fewer than three statues of boxers?

argues Gareth Jones in ‘Boxers of Wales’, published in 2011.

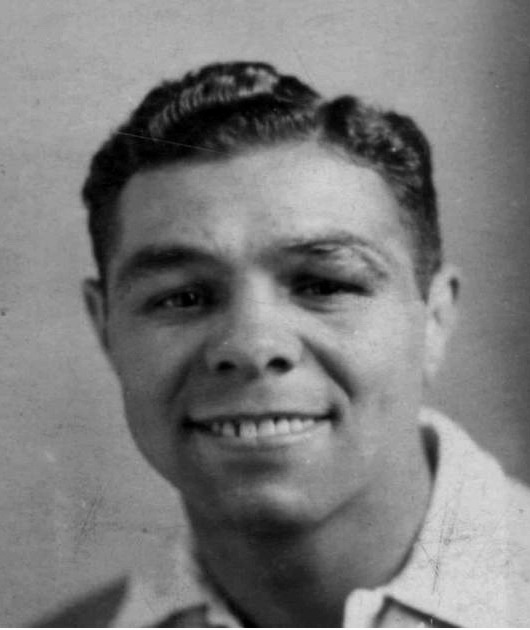

Cuthbert Taylor – circa 1925 with his Welsh and British trophies

Curtesy of the Taylor Family

Cuthbert Taylor was born in Merthyr in 1909 and began boxing when he entered an ‘open’ tournament at the age of 13 and then took part in ‘midget contests’ before main events at boxing venues in the town such as Snow’s Pavilion and the Merthyr Labour Club stadium, where he could earn up to 10 shillings per fight. Future world lightweight champion Freddy Welsh started boxing here at the age of 7.

Freddie Welsh

The Merthyr Labour Club stadium- circa 1930

At 16 Taylor was Welsh and British schoolboy Champion and he was part of a trio of schoolboy champions from the town in 1925, alongside Jerry O’Neil, who would become Welsh flyweight champion in 1930/31 and Tommy Barnes and were introduced to…

a cheering crowd from the stage of Jack Scarrott’s boxing booth and were promptly suspended by the amateur authorities

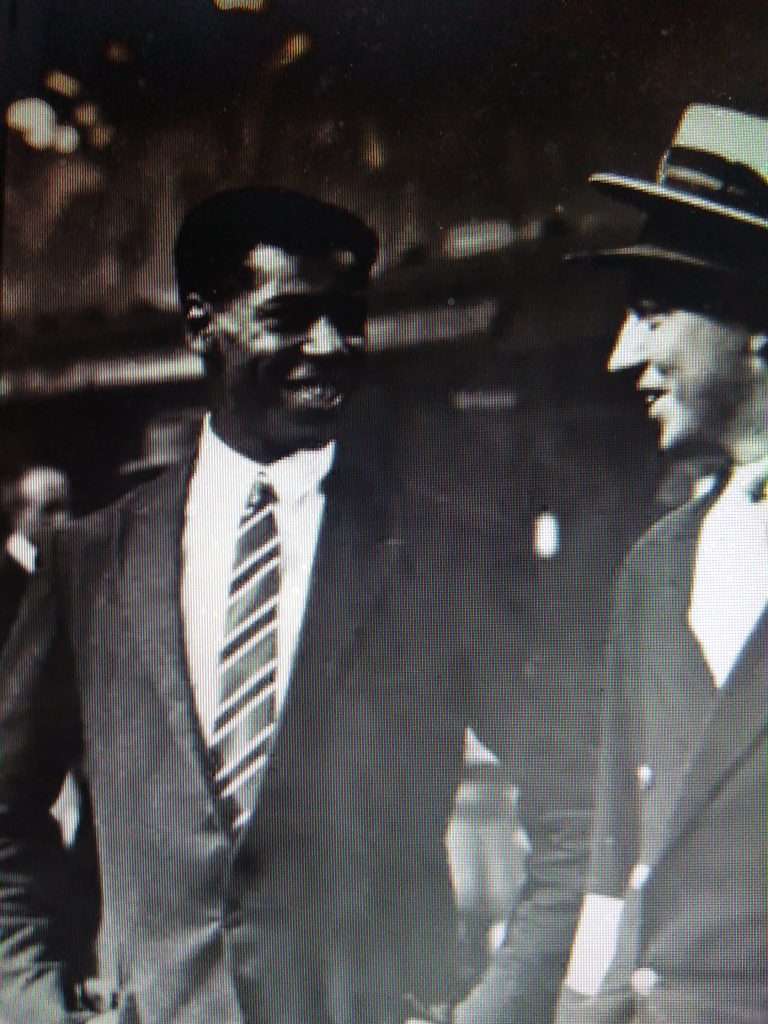

At 17 he was travelling the country with his father Charlie, an ex boxer of Jamaican heritage from Liverpool, fighting in Scarrott’s booths at fairgrounds. Booth fighters signed up for several months at a time and were given food and lodgings and a small wage, but the bulk of their earnings came from the money that was thrown into the ring referred to as nobbings, in appreciation of their performance.

Cuthbert and his father Charlie

Courtesy of The Taylor Family

The booth fighter was obliged to take on ‘all comers’, which meant that a boxer like 17 year old Cuthbert Taylor, (who would have been about 7 stone in weight) were often fighting men who were much older and heavier than them.

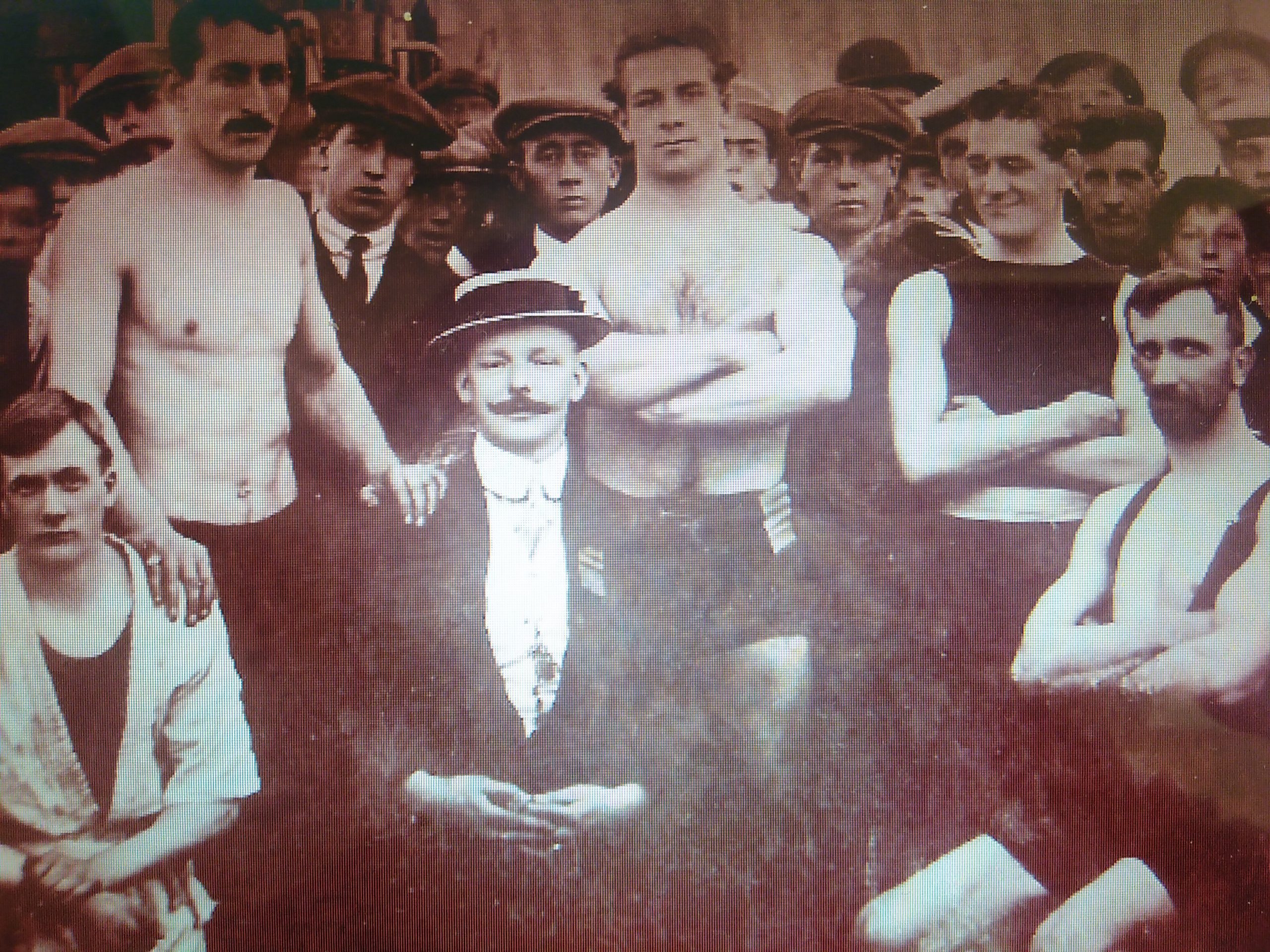

Boxing booths had been a feature of fairgrounds for over 200 years and were seen as the testing ground for many great British boxers, however by the 1950’s the authorities ruled that any licensed fighter was no longer allowed to box under these conditions and so the booths faded into obscurity; there are no active booths operating in the UK today.

- Jack Scarrott

- Boxing Booths circa 1925

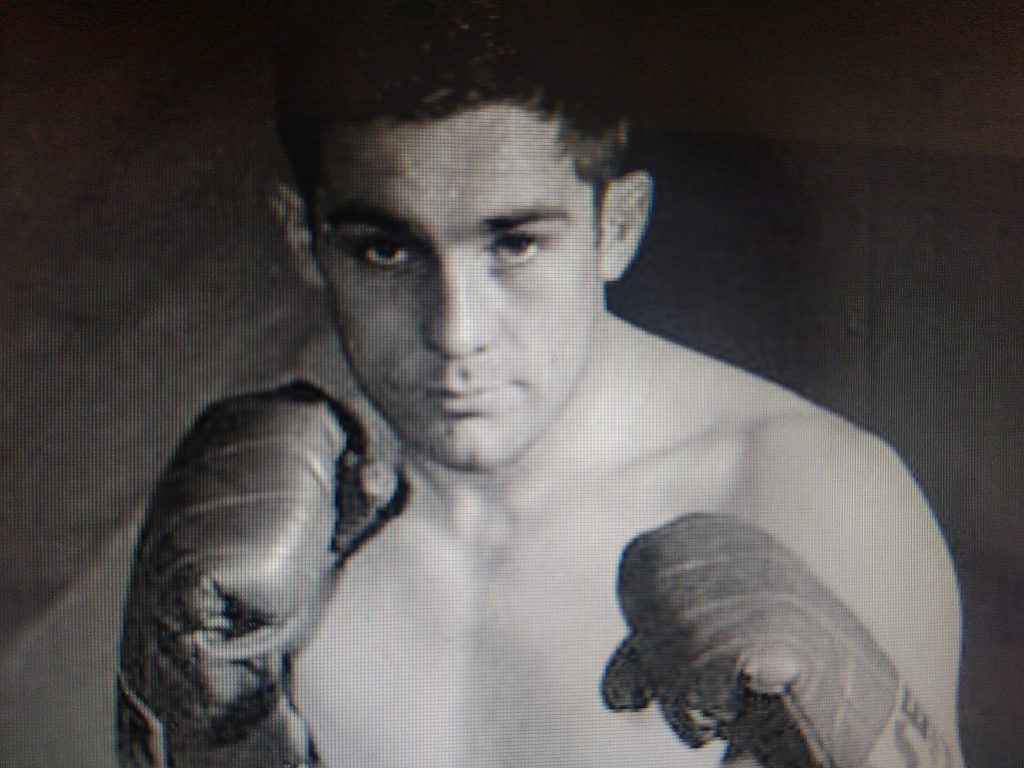

Taylor became British amateur flyweight champion in 1927 and 1928, prompting his selection for the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam, aged just 18, becoming the FIRST black or mixed race boxer to represent Great Britain at an Olympics and one of only FOUR black competitors to feature for GB since the modern Olympics had begun in 1896.

Louis Bruce (1875-1958) is the first known black competitor representing GB, in the heavyweight freestyle wrestling competition at the 1908 games in London and went on to become the first black tram driver in London.

Harry Edward (1898-1973) followed at Antwerp in 1920, winning two bronze medals in the sprint events; he would go on to become an administrator at the ‘Negro Theatre’ in New York and was instrumental in staging the first performance of Macbeth by an all black cast.

Sprinter Jack London (1905-1966) was alongside Cuthbert Taylor at the Amsterdam games and went on to win silver and bronze medals; he would go on to become an actor appearing in a variety of film roles in the 1930’s.

- .Jack London who won two Olympic medal in 1928.

-

An official stamp for the Boxing competition

Cuthbert was the first black boxer to represent GB at an Olympic games

Amsterdam was an Olympics of firsts as for the first time Greece led out the other nations in the opening ceremony with the home nation, The Netherlands, coming out last.

It was also the first games to introduce a sponsor in the form of Coca-Cola and the first to have the symbolic Olympic flame burning throughout the games. Women’s gymnastics and athletics also appeared for the first time, but it was the involvement of a greater number of black and mixed race athletes that highlighted a shift in attitude across the Olympic movement.

British boxers were apparently treated quite badly at the Amsterdam games and there was a feeling that Cuthbert Taylor had been unfairly scored by the judges (there were no referees in the ring) in his quarter final defeat, despite knocking his opponent, frenchman Armand Apell, down twice during the fight; Apell would go on to win a silver medal.

On returning from the games, Taylor competed in the Tailteann Games in Ireland (an ancient games that had been revived in 1924, where over 5,000 competitors took part) and won the gold medal beating England’s Harry Connelly in the final.

A programme from the Tailteann Games

After the Games he turned professional and moved up a weight division and became Welsh bantamweight champion in 1929 fighting out of the Cardiff Gabalfa club, beating another Merthyr boxer, Danny Dando, on points and earning £125 (£2,000 in today’s money), which would have been a fortune to a boxer who had often earned less than a pound for fights in his early days (although after tax, payment to his manager and ‘cornermen’, he is likely to have taken home around £80).

However, success was short lived and he was to lose his title in 1930 to Stan Jehu from Maesteg; it would be the last time that Cuthbert Taylor held a title of any description.

Speaking in November 2022, Taylor’s Grandson Alun said,

The Welsh Boxing Board (set up in 1928 and had amalgamated with the BBBC in 1929) were a different entity and so in 1932 they put him forward for a British title fight, but was told that in order to contest for a title, ‘you needed two white parents born in Britain’ They never let him fight for a title again, not even in Wales. He had been a champion since his schooldays all the way up until someone turned around and said, ‘your skin is too dark’

Despite this setback, he continued to fight professionally trained by his father amongst others and in a distinguished career lasting almost twenty years, he fought in over 400 bouts (many of his fights were not recorded, however as he would often substitute for fighters who failed to turn up), including fights against four world champions, one of which was the American Freddie Miller, who had held the world featherweight title between 1933 and 1936.

In 1934 he fought Miller in Llanelli in front of over 4,000 spectators, in a charity match to raise money for the families affected by the Gresford mining disaster and helped raise over £200 (£10,000 in today’s money). However neither fighter took any prize money and devoted their fees to the disaster fund.

The South Wales Echo reported that,

In the last three rounds Taylor boxed like a champion and his skilful ducking and clever slipping made Miller miss at times by the proverbial mile and trying all he knew, he could not put the gallant Welshman down! When the final gong went the two boxers were given a wonderful reception and the cheers lasted several minutes after the fighters had left the ring

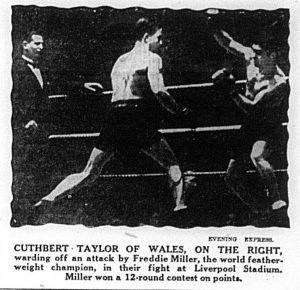

Later that year, they fought again at a packed Anfield stadium in Liverpool in Miller’s last fight of his British tour; Miller won the fight on points with Taylor again showing incredible resilience against the World Champion.

The fight against Freddie Miller at Anfield

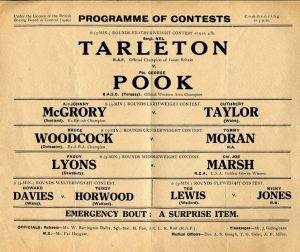

A handbill for Taylor’s fight v Johnny McGrory in Watford circa 1940

Courtesy of Miles Templeton

During WW2, Cuthbert Taylor served as a Petty Officer Physical Training Instructor and was based at the Royal Naval Artificer Training Establishment at Rosyth in Scotland, which was opened in response to the outbreak of war in 1939. He continued to box while on active service and significantly due to the war records of black and mixed race boxers like Taylor, pressure began to mount on the authorities to abolish the bar.

Cuthbert Taylor as Petty Officer P.T.I at Rothsay during WW2

Courtesy of the Taylor Family

Writing in the Liverpool Echo in 1941, ‘Stork’ argued that,

if we are not too proud to allow our coloured sons of The Empire to fight for us on the new fields of battle, surely it is time we jettisoned the mid –Victorian idea that they aren’t good enough to fight in the canvas ring for British Championship Titles

Sports Historian Gary Shaw agues that

For Britain’s black boxers, the significance of the war cannot be over-emphasised as large numbers of black and mixed race men enlisted in the armed forces and their importance to the war effort was being increasingly recognised [The Rise and Fall of the Colour Bar 2000)

Responding to public opinion, The BBBC issued this statement in 1947:

It is only right that a small country such as ours should have a championship restricted to boxers with a white heritage, otherwise we might find ourselves with a situation where all our British titles are held by coloured Empire Champions

However, they did agree to remove the bar somewhat by putting in place a slightly different regulation that meant that contestants for the British championships now had to be born and resident in Britain and that their father should also be British by birth and resident in Great Britain at the time of the boxer’s birth

However, one year later in 1948 the colour bar was remarkably abolished representing perhaps, the wider changes that were taking place in post-war Britain; in that year for example, the Empire Windrush which carried over 1,000 migrants from the Caribbean, many of which were war veterans, arrived to start a new life here and the British Nationality Act was passed confirming the right of all British and Commonwealth citizens to enter and live in Britain if they so wished.

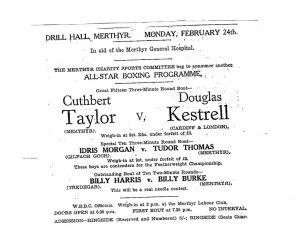

A handbill for Taylor’s fight v Douglas Kestrell for a fund raising event in 1946

Writing in 2000, Gary Shaw explained that due to,

…how widespread and popular black boxers were in the early twentieth century, WW2 played such a crucial role in the demise of the colour bar

Unfortunately the lifting of the bar came too late for Cuthbert Taylor, who had retired at the age of 38 in 1947.

After retiring from the ring however, Taylor continued to take an interest in local boxers in Merthyr, running a gym in Galon Ychaf in the town for amateurs. He also kept a keen eye on the up and coming amateurs who would later turn professional, such as Howard Winstone, who after winning the gold medal at the 1958 Commonwealth and Empire games in Cardiff, ultimately became world featherweight champion in 1968. He also offered advice and closely followed the early career of the Merthyr bantamweight, Jonny Owen, who tragically died in 1980 after a knockout punch in the 12th round of a world title fight in Los Angeles. Taylor helped Owen plan his training runs around the outskirts of the town and regularly welcomed him into his home.

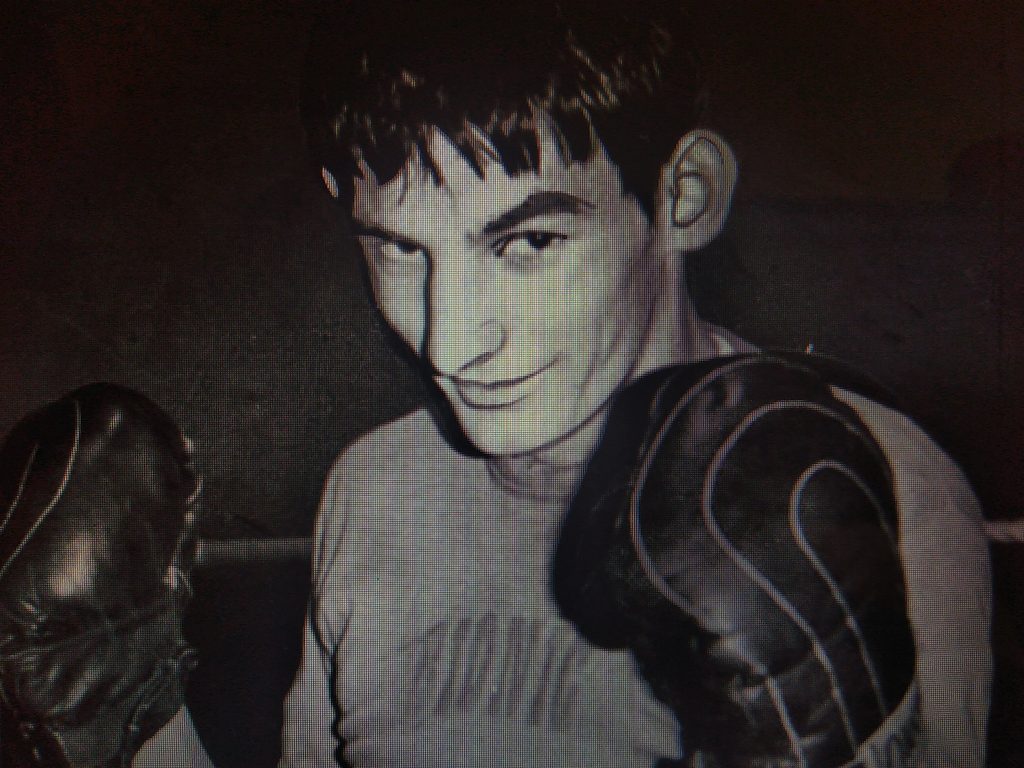

- Merthyr World champion Howard Winstone

- Merthyr’s Jonny Owen

In 1977, Cuthbert Taylor took part in a BBC documentary series called, ‘Fighting Talk: The History of Welsh Boxing’ alongside former boxing champions such as Eddie Thomas, Billy Eynon and Phineas John, where they discussed the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century phenomenon of ‘Mountain Fighting’ and ‘Boxing Booths’.

He died of a heart attack later that year at the age of 67, still living in Vaynor in Merthyr Tydfil.

In 2020 the Taylor family began approaching the BBBC for an apology, enlisting the help of Merthyr MP Gerald Jones who raised the issue of the historical discrimination in boxing in a Parliamentary debate in the same year, quoting Cuthbert Taylor as a classic example and called for a commemorative plaque to be erected in the town. During his speech Mr Jones said,

Due simply to the fact that his parents were of different ethnic backgrounds, Cuthbert Taylor would never have the recognition and success at professional level that his remarkable talent deserved all because of a rule that left a stain on the history of one of our country’s most popular and traditional sports, one that has otherwise been known for bringing people from different backgrounds and communities together

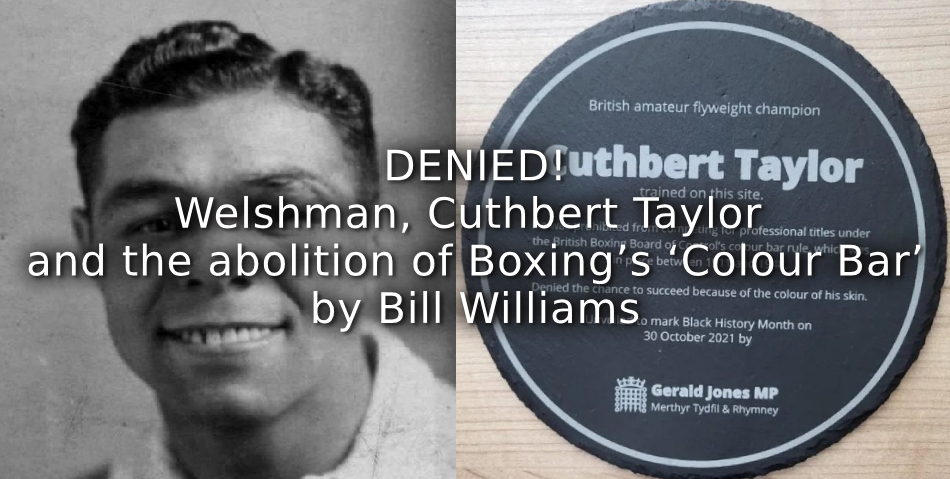

In October 2021, with the help of Gerald Jones a plaque was unveiled on the site of the gym where Taylor had trained to coincide with Black History Month. The plaque reads that Cuthbert Taylor was,

denied the chance to succeed because of the colour of his skin

The commemorative plaque erected in Merthyr Tydfil

Taylor’s grandson Alun said that he and his family were grateful for the plaque but would not be fully satisfied until they were given an apology from the BBBC. He added,

Fair is fair. I thought the way society has moved on, I thought they may have been happy to apologise and they say that they condemn what happened, but they won’t say sorry

Writing in 2020 in Boxing, Race and British Identity (1945-1962), Martin Johns and Matthew Taylor concluded by arguing that,

The abolition of the sport’s colour bar was recognition of racial exclusion and it was followed by a celebration of black fighters as local and national heroes

Richard ‘Dick’ Turpin from Leamington Spa (a friend of Cuthbert Taylor from the boxing booth days), was the first to break down the colour bar, being the first non-white fighter to be crowned British champion in any division in 1948. However, it would be Dick’s brother Randolph who would make more of a lasting impression, when in 1951 he defeated world middleweight champion Sugar Ray Robinson, on points at Earl’s Court in London, which was described as,

the biggest ever upset in a British ring

Despite losing the re match 64 days later in America, Turpin paved the way for a plethora of British, European and world champions from the black and mixed race community over the next 75 years that include names such as, Duke McKenzie, John Conteh, Lloyd Honeyghan, Frank Bruno, Lennox Lewis, Nigel Benn, Chris Eubank, Nicola Adams and Anthony Joshua, to name but a few.

In Boxing, Race and Identity, Johns and Taylor concluded that,

At a time when race relations and British identity were in flux and when race was generally discussed in the media as a problem… the successes of black boxers must have at least opened up a new dialogue around race and British culture?

The Taylor family are still waiting for the apology.

Cuthbert Taylor (1909- 1977)

Article copyright of Bill Williams

Another fascinating read, Bill. Boxing is not a sport I know much about or follow but this has sparked an interest in the many struggles of black and mixed race sports personalities which is sadly still prevalent today. The fact that games start with ‘taking the knee’ and announcements to encourage spectators to report any examples of racism, begs the question of how far we have or more importantly have not come on accepting the person and their skin colour is irrelevant. Well done. Keep writing this interesting stuff. Are your articles going to be collated and published in a book?