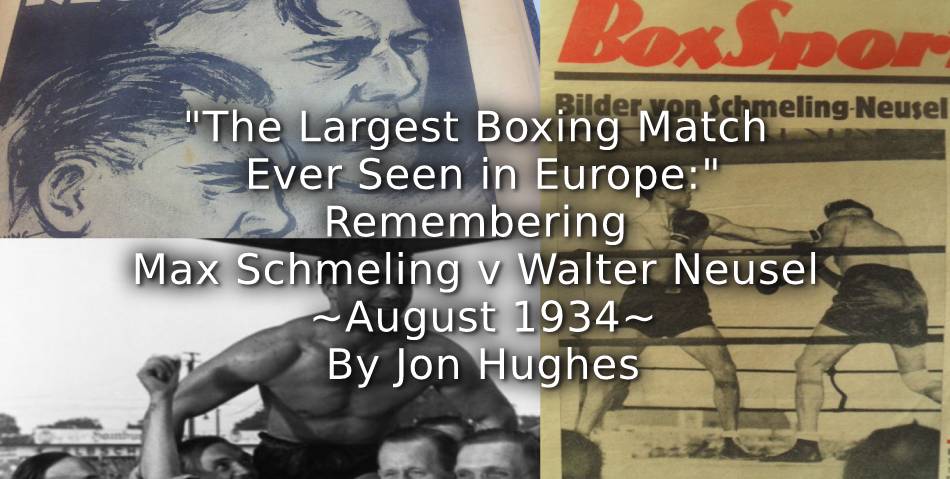

85 years ago a boxing match between two German heavyweight boxers, Max Schmeling (1905-2005) and Walter Neusel (1907-1964), took place in Hamburg on 26 August 1934. This now forgotten fight was an extraordinary occasion which saw what almost certainly remains the largest attendance at a boxing match in Europe.

Most of the crowd of close to 100,000 were eager to see Schmeling, who in 1930 had become the first European world heavyweight champion. After losing his title in a controversial rematch with Jack Sharkey in 1932 his form had dipped, and by 1934 the time seemed right for a sporting return to Germany, where Schmeling had not fought since 1928. Had he lost to Neusel, it seems unlikely that his career would have recovered.

-

Max Schmeling celebrating after his victory over Walter Neusel

Hamburg, 26 August 1934.

Photograph by Arthur Grimm. BPK Bildagentur

Reproduced with permission

The Nazis had been in power Germany since 1933, and sport was subject to the same ideological ‘co-ordination’ as other aspects of German society. In April 1933, in Boxsport magazine, the Federation of Professional Boxers had published an abhorrent declaration of its full ‘Nazification’, effectively ending the careers of German-Jewish boxers, trainers, managers and promoters.

Schmeling presented himself as unpolitical, and never joined the Nazi Party, but returning to a German ring at this point was taken by many as a sign of tacit support. Although some senior Nazis remained suspicious of international professional sport, by 1934 it was clear that the regime recognized the potential propaganda benefits of German participation on the international sporting stage. The forthcoming Olympic Games in Berlin were a case in point, and for supporters of professional boxing, regaining the symbolically important world heavyweight title for Germany became a key aspiration, as was moving the geographical focus of the sport away from the USA.

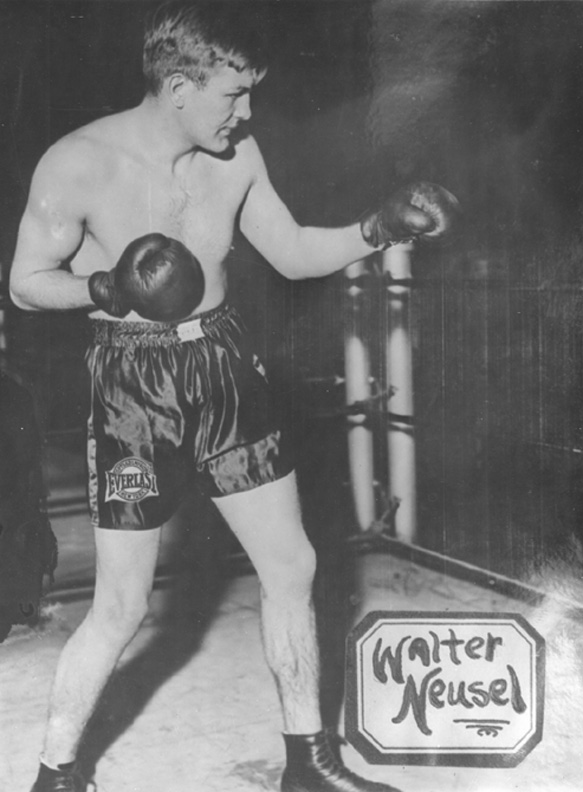

Walter Neusel was a credible German rival to Schmeling. He was ranked fifth in the world, just behind Schmeling, and a fight between the two could be marketed not only as a match between the two best German heavyweight boxers but as an unofficial eliminator bout for the right to challenge the champion, the American Max Baer.

-

Publicity shot of Walter Neusel, ca. 1933.

Source:University of Potsdam

The promoter Walter Rothenburg’s intention was for the fight both to be commercially successful and to demonstrate that Germany could stage boxing in a way that matched the great world title fights held in New York and Chicago, with their open-air arenas and extraordinary crowds. The German media coverage was steeped in nationalistic sentiment. Erwin Thoma, writing in Boxsport magazine, was just one who made clear that he viewed boxing as both a commercial and political commodity, demanding that the boxers create a global advertisement for German sport.

The fight was promoted with the co-operation of the Kraft durch Freude (Strength Through Joy) organization, sometimes referred to as the Nazi Party’s ‘velvet glove’. It offered subsidised access to approved cultural and leisure activities, all as part of a massive propaganda effort. The organisation offered subsidised tickets to the fight and transport to Hamburg in specially commissioned trains, and thus the crowd was selected in a way that was unprecedented in Schmeling’s career. Jews, for example, were excluded from Kraft durch Freude.

-

Cover of Boxsport magazine, 20 August 1934

Source: University of Potsdam

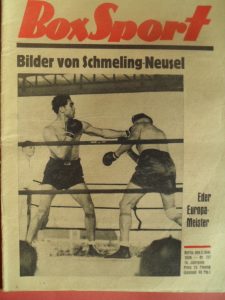

The majority of contemporary reports gave the attendance at 100,000, and they describe the ‘overpowering’ visual impact of such a crowd with something like awe. Many also praise the organisation of the event, noting the massive presence not only of the police but also of the SA, the brutal ‘Brownshirts’ who had been given auxiliary police powers in 1933. Their presence provided a signal that this was to be a strictly controlled, political occasion.

The fight took place at the open-air speedway arena, close to the Hagenbeck zoo in Lokstedt, which had been rapidly converted to seat more than 100,000 spectators. Even if the actual attendance may have fallen somewhat short of 100,000, Rothenburg could later truthfully claim that it had been the ‘largest boxing match ever seen in Europe’. The German press was happy to make exaggerated claims that it had been the best attended boxing match in history.

The fight took place at the peak of a summer that had been characterised by nationalistic ritual and relentless propaganda, culminating in the death of President Hindenburg and a referendum on Sunday 19 August that saw Hitler ‘elected’ as head of state with a 90% ‘yes’ vote. The final preparations for the fight saw the personality cult around Hitler at its most intense, and the boxing in Hamburg was preceded by rituals including the performing of the Hitler salute, now obligatory at sporting events, a triple Sieg Heil (Hail Victory) from the crowd, and political speeches.

-

Cover of Boxsport magazine, 3 September 1934

Source: University of Potsdam

Yet neither boxer had shown much commitment to the Nazi cause. Schmeling had won permission to retain his American-Jewish manager Joe Jacobs. More surprisingly, Neusel was also still working with a Jewish manager, Paul Damski, once a friend of Schmeling’s. Damski had left Germany for Paris in 1933, but Neusel had refused to break with him, moving to France to be able to work more closely with him. In the retrospective account of the fight provided by the Nazi sports journalist Arno Hellmis in 1937 neither Schmeling’s nor Neusel’s managers are named. The fact that the ‘Blond Tiger’ Neusel, who often fought in Britain through the 1930s, seemed the perfect visual representative of the ideal ‘Aryan’ no doubt counted in his favour, but he demonstrated genuine courage in his loyalty to Damski.

The fight itself lived up to expectations, and Schmeling won by technical knockout when his opponent retired before the ninth round. The consensus was that Schmeling was once again a credible contender. Many of the headlines, both domestically and internationally, acknowledged the impressive scale of the event and the size of the crowd. A few days afterwards, the Hamburger Anzeiger published an editorial reflection on its front page on the subject of ‘Sport and Politics’. The author cites the match as ‘a considerable boost to our political standing, above all because of the impressive staging given to the fight.’ Yet there never was a transfer of power in boxing from the USA to Germany, and no world heavyweight title fight took place on German soil until many years after the War.

It was precisely the association between German sport and German politics that began to be counterproductive. Schmeling repeatedly tried to distance himself, with limited success, from attempts to use him as an instrument of the regime, clinging to a myth of the athlete as a neutral figure, but this was difficult to achieve as long he continued publicly to co-operate with the Nazis. And when the first of Schmeling’s two fights against Joe Louis was finally arranged, as a formal eliminator for the right to challenge for the world title, the political symbolism, famously, became wholly inescapable.

Below is a British Movietone news report on the fight –

Article © Jon Hughes

Very interesting. Previously I had come across Walter Neusel fighting Ben Foord at Harringay in 1937, winning a disputed points decision.