In earlier works the links between the equestrian sports and athletics have already been studied extensively. Not only the practical implementations like the track and the running direction on the track have been copied from the equestrian sport, but also athletic disciplines like the 110- and 400-metre hurdles, the high jump and cross-country. Cycling was also quickly compared with horse riding from the moment the precursor of the velocipede, the draisine, appeared on the public roads some fifty years before the first official cycling races were organized in the late eighteen sixties. However, the connections with early cycling competitions are casually and vaguely mentioned although there are a lot more similarities between the two sporting disciplines than may appear to be the case at first glance.

Horses and velocipedes, jockeys and riders

In the late Georgian period horses were commonly called velocipedes, a contraction of the French words vélocité [velocity]and pédestre [by foot]. Some horses even carried the proper name Velocipede as we regularly find back in horse racing results of old newspaper articles. The name was probably inspired by a previous French contraction vélocifère, from velocity and the verb faire [to make], a name that was used for the carriage [or the horses that pulled the carriage] in the early nineteenth century.

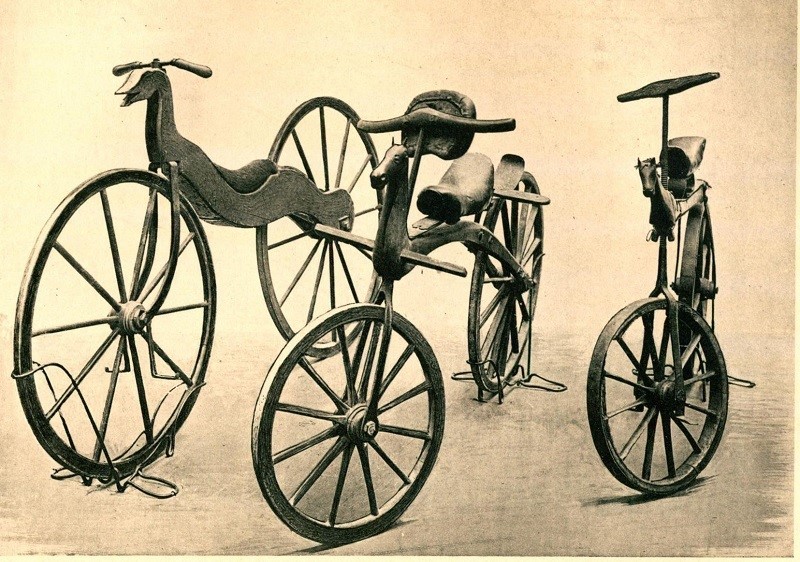

In 1818 the German baron Karl von Draise introduced his running machine in Britain. It was made of a wooden frame with a saddle in the middle, two wooden wheels placed in a row and a handlebar steering the front wheel. In the front of the frame often a horse head was carved. It was called the dandy horse or hobbyhorse because the way the cyclist rode the draisine resembled to the way horses are ridden. He had to drive the machine while sitting on it, keeping his balance and controlling the machine with his arms and legs. Pushing the machine with his feet forward it could reach the speed compared to a galloping horse.

Draisine models at the Paris World’s Fair of 1900 with the typical carved horse head frame

Source: Transportation Library, Northwestern University, Evaston

Fifty years later the first cycling races were still deeply inspired by the equestrian sporting disciplines. The bicycles that were used were also called velocipedes. The frames were first made of wood and later of cast iron. The wheels were also made of wood with a piece of metal fixed on the rim in order to protect the wheel. Later the metal band was replaced by a layer of rubber. Obviously riding the velocipede was very uncomfortable by lack of any shock absorption and the poor condition of the roads which were mostly unpaved. Especially riding over the cobblestone roads was a bumpy and even dangerous undertaking. Consequently once it was over its top in 1871 the velocipede was called the boneshaker.[1] As a means of transport the velocipede was as fast as a horse, lightweight, compact, easy to store, etc. Otherwise as a recreational and competitive object the boneshaker was fragile to breakdown and dangerous to the racers and spectators, elitist and expensive, as well as in purchase as in maintenance, compared to other leisure activities of that time.[2]

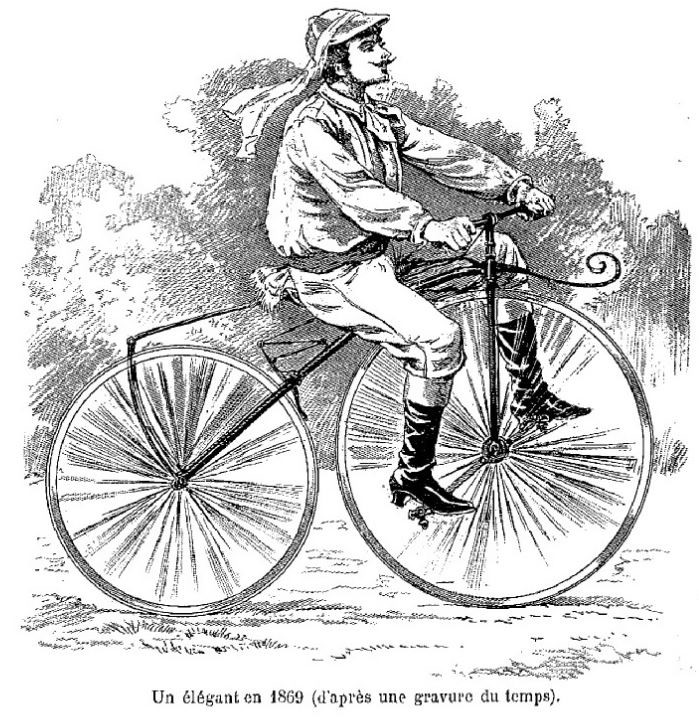

The riders, often youngsters of the better off middle and upper class families with an interest in horses and equestrian sports, called their bicycles names of horses and were even dressed like jockeys wearing colorful caps, silk jackets and high leader boots.[3]

Other links between the equestrian and cycling sport can be found in the then agricultural business and sales culture. On some occasions it happened that in agricultural stores where carriages, gear for carriages and horses and jockeys was sold also velocipedes and spare parts were available. And in the Palace of Industry, an exhibition hall erected in 1855 for the Paris World Fair and located between the Seine River and the Champs Elysées in Paris, in April 1868 a horse and equestrian sports event was organized with promotion stands reserved for several velocipede brands.[4]

From hippodromes to velodromes

As racing with the boneshaker was dangerous, in Belgium and France the cycling competitions were frequently organized on the grass fields of the horse-racing tracks in the hippodromes.[5] For example one of the world’s first official races if not the very first was held in a hippodrome near Bordeaux on 21 May 1868, ten days before the famous races in Saint-Cloud near Paris.[6] The cooperation was mostly beneficiary for both parties. The young cycling competitions were ensured of the interest of a large sports audience with a long tradition and a magnificent infrastructure for as well as the riders as the spectators. Otherwise as the early cycling races were immensely popular the hippodrome could generate a higher turnover by increasing entrance fees and bookmaking. Mostly the cycling races were organized as a playful interlude in between the horse races.

While using the infrastructure obviously it was an easy next step to copy the regulations of the equestrian competitions, and later they were also carried outside the hippodromes in subsequent road races. The distances of the early cycling races for example were measured in furlongs, which is a unit of length of 220 yards or an eighth of a mile and is still often used in horse racing. They mostly had a distance of five to nine furlongs.

Velocipede riding quickly evolved from an acrobatic sport to a recreational and competitive sport. As a recreational sport comfort was of the greatest importance, wet and dirty clothes caused by bad weather and bumpy roads had to be avoided. As a competitive sport the riders needed a track were they could train and compete each other without causing accidents with ignorant pedestrians in the streets. Again a solution was found in the equestrian sport by copying the indoor horse races. Already from 1869 entrepreneurs found a lucrative investment in building velocipede halls to organize school and training sessions during the week and exhibitions and competitions during the weekend. At first they were called velocidromes or amphibicyclotheatres, later velodromes.[7]

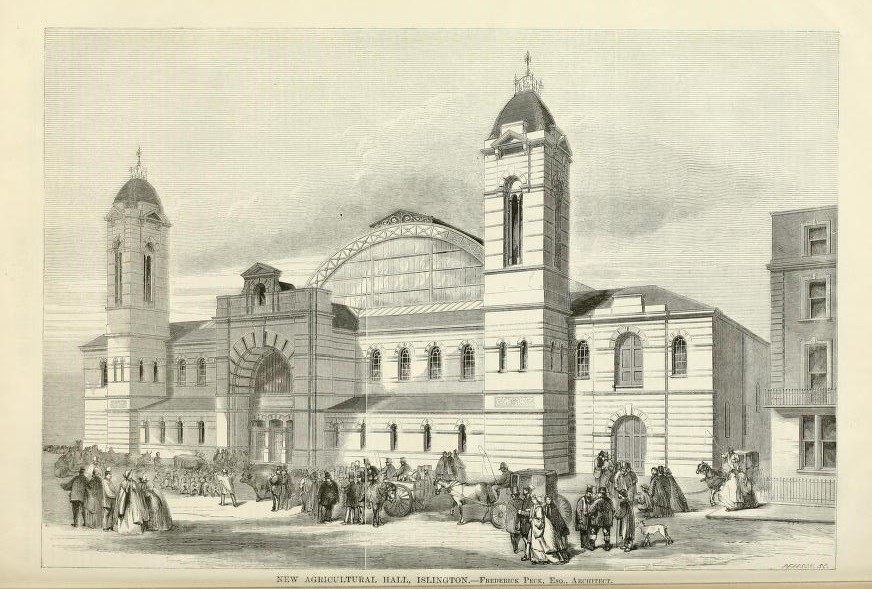

The Agricultural Hall in Islington: Britain’s very first velodrome

The velodrome of Preston Park in Brighton was build in 1877 and is considered as the oldest and still existing velodrome in the world. But this research has revealed that there were already temporary velodromes in use at the same period of the nascent cycling competitions.

Shortly after the cycling races of Monday April 5th and the Velocipede Derby on Thursday 27 May 1869, both at the Crystal Palace, an exposition of velocipedes in the Agricultural Hall of Islington emphasized the strong connection with the equestrian sport.[8] Up till then the Agricultural Hall was the scene for jumping competitions, horse races, exhibitions, circus acts, etc. However, on Saturday 30 May 1869 the sixth Metropolitan Horse Show was opened with 360 exhibited horses in the big hall, while a velocipede exposition was organized in the galleries.[9] The week after the whole infrastructure of the Agricultural Hall was temporarily transformed into a velocipede practice school and racing arena.

The Cardiff Times of 19 June 1869 reported that

“… The Agricultural Hall in Islington was opened to the on Saturday in a novel capacity –that of a velocipede practice school and racing arena.” and “The Hall has been converted into something as near a ring as possible by enclosing in an immense oval the whole arena of the Hall”.

The Agricultural Hall in Islington, 1962

Source: Building News and Engineering Journal – 5 December 1862

The wooden floor of the arena was strictly reserved for cycling purposes. It was used for try-outs of the several available brands of velocipedes, for interested visitors who could rent a velocipede for 1 shilling per hour, and of course for the organization of cycling exhibitions and races.[10]

On Saturday 12 June 1869 a cycling contest was organized with twenty three participants divided over six heats. A race had a distance of one mile or nine laps around the oval. Several riders ended their race crashing into the barricades of the oval without any serious injuries. Under a large attendance of spectators the final race was won by J. Hook after a tremendous spurt against his opponent R.B. Turner at an average rate of fifteen miles per hour.[11]

Nine years later the first six day bicycle race would be contested in the Agricultural Hall, following the example of the pedestrian six day race in April 1877.

Cultural interdisciplinary: industrial, sports and art history

Halfway the nineteenth century the impressionism was a new style of painting that among other focused upon daily life and the new innovations of industrial modernity. Consequently it could not take long before the velocipede became the subject of interest of this new art movement.

Samuel Henry Gordon Alken [Ipswich, 1810 – London, 1894], son of Henry Thomas Alken and better known as Henry Alken Junior was popular for his paintings of equestrian, hunting and sports scenes in a rural environment. In 1869 he made ‘A race between Lallement velocipedes’, an early impressionistic painting.[12]

‘A Race between Lallement Velocipedes’ by Samuel Henry Gordon Alken [1869]

It is the only painting with velocipedes as subject made by Samuel H.G. Alken. In this work he is comparing horse races with cycling races by replacing the horses by velocipedes. He is dismissively making fun of the velocipede as the alleged substitute of the horse, and of the young cycling sport by depicting all that can go wrong during a horse or cycling race. He is showing the cinematographic threefold succession of physical motion preceding, during and after a crash, with the final embarrassing run of the rider [jockey] after his velocipede [horse].

Cultural and historical related adaptations.

During its first years the cycling mania knew an in parallel related bicycle-replacing-the-whatever mania. Some experiments were interesting and would somehow survive for at least a few years like the invention of the tricycle which is still in use by children or the water bicycle, now better known as the pedalo. Others were dangerous and completely bonkers. Certain adaptations were cultural or geographical related and went far away in time, from the Middle Ages even towards the Greek-Roman culture.

Part 1: The chivalrous legacy of the Middle Ages

The jousting tournaments came to an end in the sixteenth century on the mainland and the early seventeenth century in Britain. However non-combat related competitions and acts survived in medieval festivities and are still organized. In tilting at the ring the knight has to aim his spear in a metal ring hung up instead of touching the helmet or the shield of the opponent in the lethal jousts.

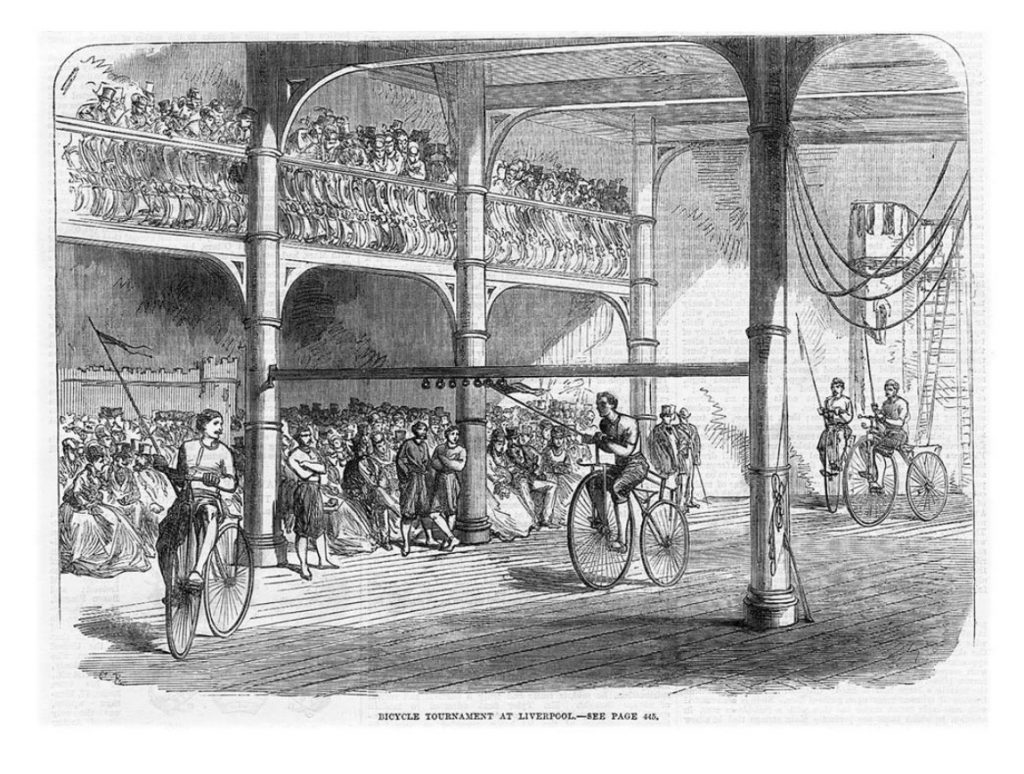

After Britain’s first official cycling races Liverpool-Waterloo and Chester-Birkenhead a few weeks earlier, on Saturday 24 April 1869 the Liverpool Velocipede Club organized a bicycle chivalry tournament in the Liverpool Gymnasium in Myrtle street. The Liverpool Velocipede Club was founded by the manager of the Gymnasium John Hulley who saw an economical potential for his gymnasium. Consequently the whole event was organized in the perspective of using the velocipede as a mean of exercise and gymnastics.[13] the Aberystwyth Observer of 1 May 1869 reported the event as

‘a great variety of bicycle practice was exhibited, such as tilting at the ring, throwing the javelin, fencing with swords and ‘sundry passages of arm’. The most amusing of the performances were the encounters with lances between two knights of very redoubtable appearance, who in coats of mail, entered the lists in truly chivalrous style. They were the Knight of the Red Cross and the Knight of the Black Cross. The former was mounted on a bicycle, which was made to approach as nearly to the appearance of a charger as a griffin-like head fixed upon the front and a housemaid’s brush suspended behind could make it. The knight who unseated his adversary thrice in five encounters was to be declared the victor.’

Source: The Illustrated London News of 1 May 1869

The Brecon County Times Neath Gazette started its article with:

‘Bicyclian Chivalry: velocipede tournament at Liverpool’ and continued ‘…There was also a steeple chase on bicycles over mats, Mr Hollins representing a ‘Girl of the Period’, and working the bicycle in the position of a lady on one side of the saddle. Messrs R. and E. Yeaves were jockeys in pursuit, and J. Currey was a huntsman. The pursuit of the ‘Young lady’ caused roars of laughter.[14]

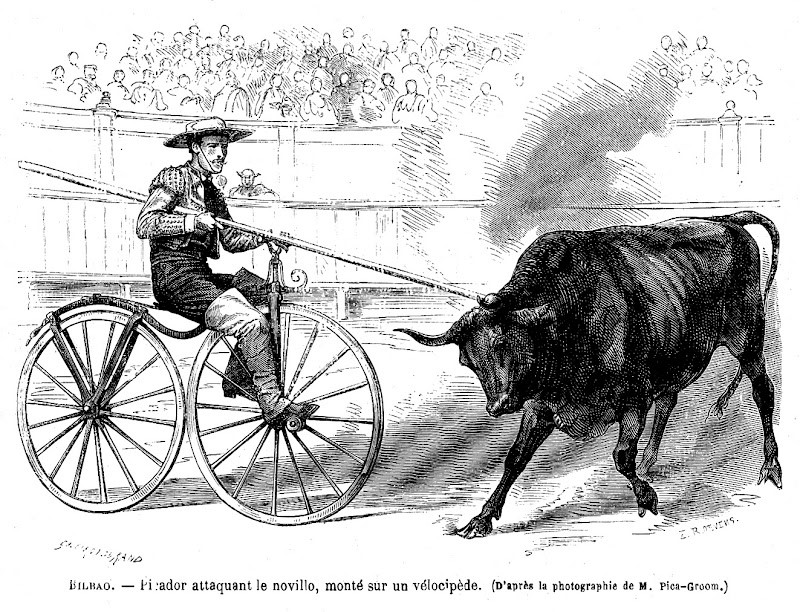

Part 2: Bull fighting with velocipedes in Hispania

Bull fighting goes back to thousands-years-old traditions. In the Greek-Roman culture they were organized during the Venationes, where gladiators, captives and condemned criminals faced wild animals. According to certain resources bull fighting survived in Spain because it replaced the jousting tournaments at the end of the Middle Ages.

One of the most hilarious try-outs in horse related local practiced sports and leisure activities was the usage of bicycles during bull fights in Southern France and Spain. In June 1868 a bull fight took place in Bilbao where the picador faced the bull on a velocipede instead of a horse.

Source: Le Monde Illustré [Fr] 27 June 1868

‘… The bull did not know what to do when he first saw the velocipede turning and maneuvering, surprised as he was he shook his head on a funny way every time he saw the picador riding into his direction. Finally he ran into the bicycle and the picador fled away while making curves and zigzag turns. After a few moments of recuperation the bull started chasing the picador who -to protect himself- threw the velocipede upon the horns of the animal. Full of fear and anger because of this strange machine fixed upon his head, the bull furiously started to run and jump about in the arena. Finally the spectacle ended with the killing of the velocipede to loud cheers from the crowd roaring with laughter.’

From steeple chase to cyclo-cross?

The first traces of cyclo-cross competitions we find back at the end of the nineteenth century. According to the resources there are several assumptions concerning its origin.

One theory says that cyclo-cross racing was invented by the French army at the end of the nineteenth century. Compared to a horse the folding bike was as fast as but a lot smaller and thus tactically more interesting, lightweight, compact and easy to store and therefore mainly used for reconnaissance and liaisons purposes in the infantry and chasseur battalions. The intensive training sessions automatically introduced a competitive component leading to the first cross-country races.

Another supposition we find back in the bicycle balloon races during the eighteen nineties in France and Belgium. The bicycle race started at the same time and at the same place where the balloon took off, in the cities often in a velodrome. The racers followed the balloon and had to take shortcuts through the fields and woods. The finish was the place where the balloon landed, mostly followed by a bicycle race back to the starting point. The next step was organizing a race without balloons but with a predetermined finish line or turning point in another village.

Thirdly and shortly bordering to the previous argument, by the turn of the century the road racers started to train in the country side during the winter time in order to keep in shape before the start of the next season. They raced to the next village and back more or less in a straight line while cycling and running off road on the country roads and through the fields, which kept them warm during the coldest days. The turning point was mostly the church of the village as it could be recognized from a large distance, just like the early horse steeple chase races used to be organized -from steeple to steeple- way before the first hippodromes were constructed.

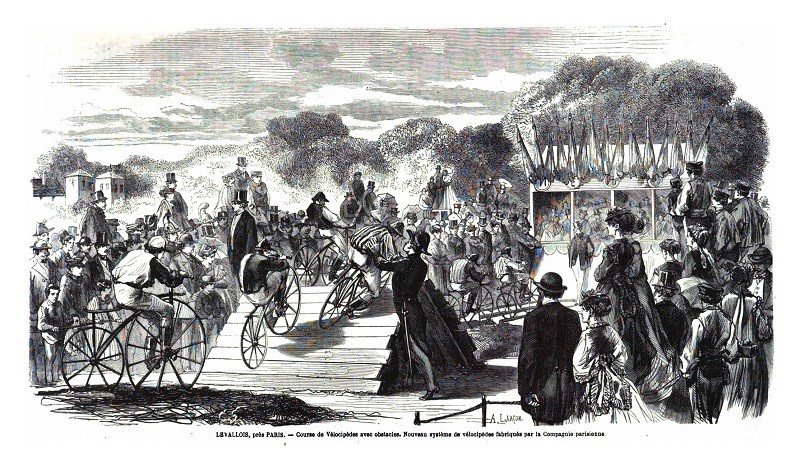

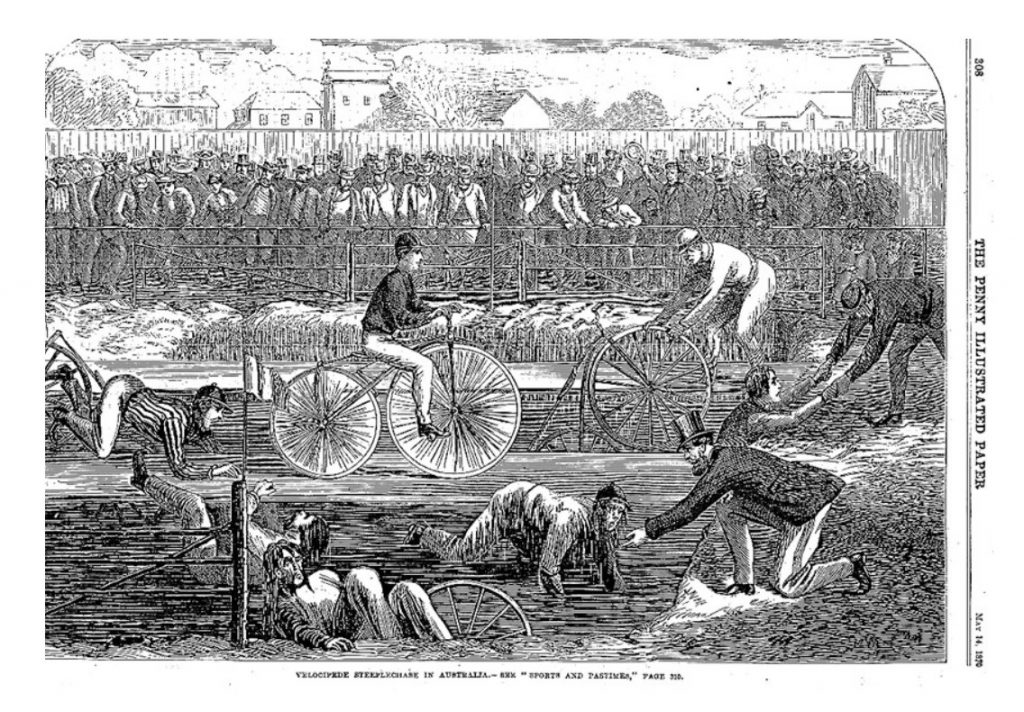

However, thirty years before the turn of the century during a very short period of time something most interesting happened in the nascent cycling world. A lot of newspaper articles and posters with announcements in Belgium and France indicate that a few months after the first cycling competitions in 1868 different kind of races were organized which were also inspired by the equestrian sport. The track of these races [often the same as the speed races] was interrupted by several obstacles. The general idea obviously came from the steeple chase races. The French newspaper L’Illustration of 21 August 1869 reported that:

the velocipede races rival with those in the hippodromes by organizing races with obstacles as you can see at our image.

A velocipede race with obstacles in Levallois near Paris

Source: L’Illustration, 21 August 1869)

There were several kinds of obstacles or hurdles to cross like a wall of tilted shelves [see image], a pivot point, a piece of plowed soil and a moat. They were placed on the track at regular distance intervals, mostly one obstacle every hundred yards. The obstacles as shown on the image have disappeared, but bicycle races with obstacles on a [closed] off road circuit are now better known as cyclo-cross races.

The quick disappearance of proto-cyclo-cross

The surprising effect of seeing someone moving forwards on a machine by own manpower balancing on two wheels in line for the very first time must have been quite a shocking experience. The first cycling races were probably seen as a curiosum or a kind of acrobatic act, considering the amount of spectators that turned up. However, during the early eighteen seventies the velocipedes and cycling competitions lost most of their popularity. For the first time velocipedes were sold at public auctions ushering the end of the first cycling mania.[15] In November 1875 a velocipede race in Brussels was even canceled by lack of participants.[16] Around the same period cycling reached the turning point from a spectator and acrobatics sport to a competition and leisure sport. Constructors quickly understood that, once the ‘acrobatic magic’ was gone, the cycling mania would be over. Consequently they started to focus on the competitive aspect and looked for a solution to increase the speed of the velocipedes. Already from the period of the first cycling races the shape of the velocipede was constantly changing. Especially the size of the front wheel of the race bikes developed at a quick pace and became larger than the back wheel: the larger the diameter of the front wheel, the higher the reachable speed. From 1869 sometimes the speed races were divided into several categories based on the size of the front wheel and also handicap races were introduced.

A rider dressed like a jockey on a competition 1869 Michaux velocipede with a larger front wheel and

breaks at the back wheel.

Source: Le Cyclisme théorique et pratique [17]

Another reason for its disappearance and the decreasing velocipede races in general is the French-Prussian war in 1870-1871. The velocipedes for normal usage were very fragile and susceptible to mechanical breakdown, and the machines used for obstacle races obviously even more. In the Northern parts of France no cycling races were organized due to the battles and later occupation of the German troupes till 1873. As the surrounding countries on the European mainland where an important market for the French velocipedes there was a seriously distorted supply of new bicycles and spare parts as several brands had their manufactory based in the neighbourhood of occupied Paris. In Britain the cycling competitions could continue as it stayed out of the conflict. The supply lines from Europe and the United States were hardly interrupted while the center of the bicycle industry moved from Paris to Coventry.[18]

Velocipede steeplechase in Australia in Sports and Pastimes

Source: The Penny Illustrated Paper [Australia], 14 May 1870

It is quite obvious that during the period of the hobby horses the inspiring influence of horse riding was very visibly present and confirmed during the appearance of the first Michaux and Lallement velocipedes in the early eighteen sixties. From the first cycling competitions there was a successive and systematic kind of copy-pasting of disciplines, organizational regulations and infrastructure-related innovations. The short succession of all new and different aspects of the cycling sport, lent to the equestrian sport or leisure activities where horses were involved, were quickly put into practice. One practical development of a copied idea automatically led to the next one. The far-reaching comparisons with horses fostered the general idea that in the near future the bicycle would become a substitute for the horse in the Western society.

Unfortunately the cycling mania became a passing fad, mainly due to lack of comfort of the velocipede, the poor condition of the roads and the outbreak of the French-German war. It lasted another thirty years and a lot of technical modifications before the bicycle experienced a democratization process and became the real mechanical horse [of the working class] short after the turn of the century.

Article © Filip Walenta

References

[1] Clayton Nick, The Birth of the Bicycle (Stroud, 2016)

[2]Herlihy David V., Bicycle, the History (Yale University Press, 2004), 30 < https://books.google.be/books/about/Bicycle.html?id=VDlaT0KxJfAC> [Accessed June 29 2020]

[3] The Velocipedist, February 1, 1869, 5

[4] Le Petit Journal, April 16, 1868, 2

[5] Ritchie A, Early Bicycles and the Quest for Speed: A History, 1868-1903 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Compagny, 2011), 326 <https://books.google.be/books/about/Early_Bicycles_and_the_Quest_for_Speed.html?id=c51NDwAAQBAJ > [Accessed June 29 2020]

[6] La Gironde, May 4, 1868, 2; May 21, 1868, 3; May 25, 1868, 2

[7] Le Constitutionnel, May 12, 1869, 3; Gazette Anecdotique, February 28, 1869, 107

[8] The Oxford Times, April 10, 1869; The Western Mail, May 29, 1869, 3

[9] Le Courrier de Bourges, June 4, 1869, 2; Monmouthshire Merlin, June 5, 1869, 1

[10] Le Ballon, June 13, 1869, 3; Le Français, June 12, 1869, 4; La France, June 8, 1869, 2

[11] The Cardiff Times, June 19, 1869, 6

[12] The work can be classified as impressionistic because of the sketchy and unfinished style, the outside blurry and diffused lighting, the theme that refers to new innovations of the modern world and the focus upon the impression/momentum of motion and speed.

[13] Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Hulley> (Accessed: June 26, 2020)

[14] The Brecon County Times Neath Gazette, May 1, 1869

[15] Het Handelsblad, August 6, 1869, 2

[16] La Meuse, November 5, 1875, 2

[17] Louis Baudry de Saunier, Le Cyclisme théorique et pratique (Hachette Livre – BNF, 2014), 49

[18] Clayton Nick, The Birth of the Bicycle (Stroud, 2016)