Please cite this article as:

Walenta, F. Military Regulations Suppressing Sports Movement: Cycling During the Great War in Occupied Belgium, In Day, D. (ed), Playing Pasts (Manchester: MMU Sport and Leisure History, 2020), 151-161.

ISBN paperback 978-1-910029-56-5

Chapter 10

______________________________________________________________

Military Regulations Suppressing Sports Movement: Cycling During the Great War in Occupied Belgium.

Filip Walenta

______________________________________________________________

Abstract

As sports and leisure activities behind the front lines in occupied Belgium during the Great War have been rarely examined, the purpose of this study is to get a clear idea about the way sports, and especially cycling, were engaged in during this difficult period. A deeper insight is revealed into how German regulations influenced the local mobility and cycling in particular. Also, sports competitions were difficult to organize. The cycling races became local events with local athletes and the way they were structured changed significantly. The national competitions were cancelled for four long years and the functioning of the cycling federation was reduced to an absolute minimum. Nevertheless, sports competitions, including cycling races, survived in other forms due to the innovative ideas of the organizers.

Keywords: First World War; Sport; Cycling; Mobility; Belgium.

Introduction

On Sunday 28 June 1914 two events happened at the same moment: the departure of the twelfth Tour de France in Paris with a total distance of 5404 km divided over 15 stages, and the assassination of the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand II and his wife Sophie Chotek by the Serbian nationalist Gavrilo Prinčip in Sarajevo, causing a snowball effect that would lead to the beginning of the First World War.

Five weeks later. on Sunday, 2 August 1914. Philippe Thys, the overall winner of the Tour de France for the second time in row, was celebrated at his arrival in the railway station in Brussels.[1] A cycling race in the velodromes of Brussels and Ghent on Monday was planned with Thys, but cancelled due to the threat of war.[2] Instead of earning extra prize money as a guest racer Philippe Thys took his luxury car to the nearby military camp and volunteered in the Belgian army.[3] At the same day Luxemburg was invaded by German troop and two days later they crossed the Belgian borders. Obviously, all sport activities were cancelled during their Westerly progression through the country. The editorial office of the leading sports newspaper Sportwereld wrote:

It will not surprise anybody that today we are not able to provide any sports news or any results of cycling races. The people are sufficiently enough informed about the international complications to realize that the general attention is focused upon other things than amusement. Consequently, all cycling races in the country are cancelled.[4]

At the end of October 1914, the progression of German troop into Northern France came to a standstill, and the movement of war changed into trench warfare.

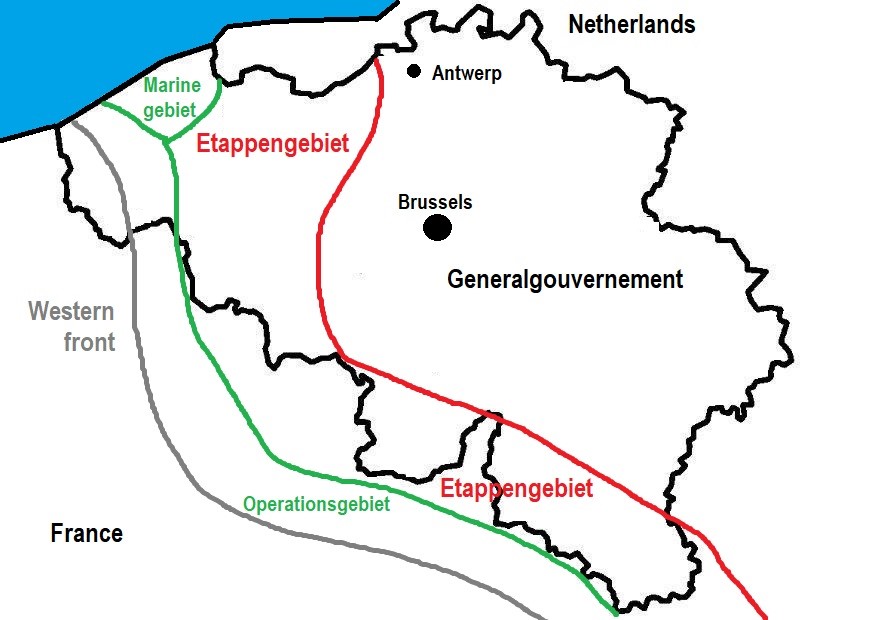

Sperrgebiet, generalgouvernement, etappengebiet, operationsgebiet and marinegebiet.

As the Western front was situated near the Belgian-French borders Belgium was consequently divided into two parts: the Kaiserliches Deutsches Generalgouvernement Belgien and the Sperrgebiet.[5] The General Government was a civil occupation authority while the Sperrgebiet was a military area under the command of the 4th Army. It was prohibited for civil traffic and divided into three areas: the Marinegebiet, Operationsgebiet and Etappengebiet.[6]

The Operationsgebiet (area of operations) was a 10 to 15 kilometres wide strip following the Western front from the North Sea towards the Suisse borders. The Marinegebiet near the coast that had to be secured against an eventual invasion of allied troop was also considered as an ops-area, especially the harbour of Ostend as the U-boat headquarters deployed there needed extra protection.[7]

Figure. 1. Map of Belgium during WWI divided in several strategic areas

In Etappengebiet we recognize the French word étappe. Today étappe is a French term for a day race in a multiple (bicycle) stage race, like the Tour de France. The place of arrival of a stage is mostly the starting point for the next stage the day after, this is why it is considered as the resting point. But originally it was a French military term, meaning ‘resting point for the army’ in the eighteenth century, and later in the nineteenth century ‘distance between two military resting points’ or the distance that an army could cover in one day. As the army could progress approximately forty to fifty kilometres per day, the Etappengebiet was a forty to fifty-kilometre-wide area that followed the troop in the frontal zone.

With the quasi stationary Western front almost parallel to the French borders, the whole area West of Brussels and the Southern parts of Belgium remained Etappengebiet during the whole war. As there was a lot of movement it was a logistical and administrative area for the supply of fresh troops, weapons, ammunition, material and vehicles, and also a resting place for fresh and returning troop with a lot of (field) hospitals for wounded soldiers.

In order to assure a smooth transition of troops, weapons and material, and to avoid sabotage, espionage or revolts, a harsh regime for the civilians was installed. Therefore, several regulations for the local population were introduced. Crossing municipal borders was forbidden without a pass, all public festivities on the street were forbidden, especially national holidays and public (sport) events in the street.[8] As a consequence, relatives and friends who lived in different villages did not see each other for four years. The only possible communication between them happened by exchange of letters. In addition, people who had fled their homes during the period of the German invasion and wanted to put their families’ minds at rest wrote small announcements in newspapers.[9]

Mobility and sports

Cycling in Operationsgebiet en Marinegebiet was prohibited, especially on certain strategically important traffic lanes. In the Etappengebiet and Generalgouvernement initially cycling was prohibited as well, but later from spring 1915 it was allowed in the cities and outskirts but (as mentioned before) crossing municipal borders was forbidden. For those who had to use their bicycle and needed to cross the borders for professional reasons a special pass valid for an area of five kilometres radius was available. The pass had to be requested and renewed every fourteen days in the office of the local German headquarters.

All kind of sports and leisure events on the street were forbidden and were banned in sporting fields and gyms. As a consequence, the younger team sports gained popularity very quickly. Football, for example, was one of the sports that became popular in Belgium during the Great War due to unemployment and the restrictions on crossing municipal borders. In 1915, regular football competitions were organized again in the bigger cities Ghent, Brussels and Antwerp, but only with clubs from within the city borders, while in the suburbs and the countryside new clubs were founded at a very fast pace.

Stijn Streuvels, a Flemish naturalistic author wrote in his diary that would be published ten years after his death in 1979:

The new phenomenon is football, the game that used to be played only by sportsmen and students. Before it was completely unknown in the countryside, but now football is played everywhere. Every village got her own club and when an appropriate field is found, the game is on.

and, ‘Every kind of game was being played, adults would even play marbles just to kill the time’.[10]

Cycling races and athletes

In consequence of the German regulations, cycling races in the street were forbidden in the whole occupied area, except in Brussels where very occasionally a street race was allowed. These races were organized inside on home trainers and rollers during wintertime, and in velodromes during the summer, including the classic races. This was not new because in 1911 the classic Sedan-Brussels had been organized in the velodrome of Linthout near Brussels.[11] The track on the street was projected into the velodrome and all regulations were at force as during the classic races. The racers had to restore their own bicycle during any break-down and were not allowed to get help from anybody. During their ‘passage in the cities’ check points were organized to avoid cheating and to be sure everybody had done the complete distance. The racers had to stop and sign the participant’s list or get a stamp on their jersey number. At the check point the participants could have some extra food and drinks, spare tyres and material.

Most of the bicycle races that were organized during the First World War in occupied Belgium have been forgotten for the last hundred years but these have been revealed since the start of this study. As a single event they do not have any significance at all, except for the classic races that carry a famous name. But all together they show that the sporting and cycling life was pretty much alive, and that the statement by some authors that ‘cycling died a quiet death during the First World War’ as we will discuss later in this chapter is based upon personal interpretation and loose ends, caused by several different reasons.

The Ghent Six Day race, for example, was until now considered to be organized for the first time in 1922. Nevertheless, this study revealed the existence of the very first edition in 1915 from Sunday 3 till Monday 11 November, around the same period of the Brussels six-day race. The race was organized over nine days, with in between three days off, divided over three velodromes in the outskirts of Ghent: Mariakerke, Gentbrugge and Evergem.[12] The duration of the day stages of the races resembled much of the six days as we know them today. Instead of the continuous six days by teams of two members the races took six hours on Sundays and four hours during weekdays due to the compulsory curfew.[13]

Figure. 2. A hundred-kilometre cycling race at the Karreveld velodrome (Brussels) on June 12, 1915.

Another forgotten cycling classic is the Tour of Flanders of 1916, organized in the Gentbrugge velodrome on Sunday, 23 July 1916 as a 125-kilometre race with four intermediate sprints after 25, 50, 75 and 100 km.[14]

According to previous sources, Karel was supposed to be the organizer of the Tour of 1915.[15] He apparently heard about the cycling race in the Brussels velodrome in June and remembered the success of the Tour of Flanders in 1914, jumped on his bike and drove to the Evergem velodrome to organize the Tour of Flanders. But, as Karel lived in Torhout, a very important garrison in the Operationsgebiet, he simply never could have got the permission to leave his town for such an ‘insignificant’ reason, and certainly not for a longer period to make all the preparations. Also, in 1916 there had to be another organizer as Karel was forced to work for the construction of the airfields near his town.[16]

New-found information about cycling events in Ghent in 1916 has revealed the real organizer. According to newspaper articles some of the cycling races were organized by the magazine Sportwereld.[17] A small article mentioned that Leon Van Den Haute, general manager of Sportwereld and founder of the Tour of Flanders, lived in the centre of the city of Ghent and married his fiancée Elodie Dick on the same day of the race.[18] So it was quite clear that Van Den Haute must have been the organizer of the Tours of Flanders during the German occupation or at least must have given the permission to use the brand name.

Just like the rest of the Belgian population, cycling racers spread out over whole Europe during the First World War. The biggest number stayed in occupied Belgium and found extra jobs to survive as they mostly donated their prize money for charity purposes like war orphans, prisoners of war in Germany, etc.[19] Smuggling foodstuff and transferring espionage letters, photos and microfilms became a lucrative business for the daredevils of the cycling peloton. Among them Paul Deman, winner of the first Tour of Flanders in 1913, who did several missions until he was arrested by the Germans. After questioning and torture in the prison of Leuven he faced the death penalty but was finally rescued by the Armistice in November 1918.[20]

A lot of cyclists had joined the army and stayed for four years at the Western front, eventually being killed in action or taken as prisoners of war. Philippe Thys had brought his car and drove high rank liaison officers about from one meeting to the other. During his time off he kept on training and even succeeded in winning the cycling classics Paris-Tours and the Tour of Lombardy in 1917.[21]

Others had fled to the Netherlands after the battle of Antwerp and lived in refugee and prisoners of war camps. To kill time, they managed to build a velodrome in the Harderwijk camp and organize cycling meetings. From the camps in Holland a few even migrated to the United States to compete six-day races, like Michel Debaets and Victor Linart.[22] In general they also donated half of their prize money to charity organizations in Belgium.[23]

As cycling racers were considered as adventurous acrobats some of them were recruited as pilots in the air force. Among them was Hélène Dutrieu, a former female cyclist who obtained her flying license in 1910 as the first Belgian female pilot.[24] During the war she led Red Cross ambulances and later the field hospital in Val-de-Grâce.[25] Rumours have it that although female pilots were not allowed in the French air force she did some recce flights and also participated in the air defence of Paris against zeppelin attacks, but until now no proof of this has been found.

Cycling died in 1916?

A few resources mention that the cycling movement decreased significantly from 1916. This statement is generally based upon a mixture of several facts and personal impressions. Two events at the turn of 1915 were of political nature and had a hidden but immediate effect upon the ordinary life in Belgium. King Albert I had seen the thousands of casualties caused by the mindless attacks of allied troops, only to gain a few hundred square metres and to lose them again a couple of days later. He feared that his troops would suffer the same fate and refused to bring them under the general command of the allied forces. A second reason for his refusal was that he did not want to give up the neutrality of his country. This was the official version. The unofficial reason was that in the autumn of 1915 there were high level diplomatic contacts between the close entourage of the king and the German government without the Belgian government’s involvement. King Albert I thought that there would never be a victor of the war and it would be better to make a compromise peace with Germany. However, in February 1916 he rejected the German terms, broke off the negotiations and brought the Belgian troops under the general command of the allied forces after the successes at the battles near the Marne in July 1918.[26]

The continuous poverty of the German working class, the long duration of the war, and the status quo position of the Western front led to the emergence of war-weariness in the German cities. The increasing political response of left-wing parties put extra pressure upon the government and the military authorities in Berlin. Consequently, in the autumn of 1916 the German army responded with increasing attacks on the Western front and a harsher regime for the local population. The country was treated as a German colony, everything that could help the German troops was confiscated. Food distribution happened infrequently, and meat was rationed to only 150 grams per person per week.[27] Zivilarbeit, forced labour, was introduced for the unemployed locals living in the Etappengebiet. They were transported to Northern France near the frontal zone to work under horrible conditions. According to a study conducted by specialist-researcher Donald Buyze almost eight thousand civilians would not survive German slavery.[28]All the bicycles and rubber tyres were confiscated, except for those who needed their vehicle for professional purposes. Consequently, there was a lack of everything, bicycles and cycling material included.

Alongside these difficulties came the demolition of several velodromes. The two most important velodromes in Antwerp and Brussels were demolished because the land was bought by investors for the construction of new sports halls and fields, wooden velodromes like those in Ghent and Aalst were broken down due to increased wood prices and lack of investment. Other places saw an increase of cycling races and sports events like the Gentbrugge velodrome, while the velodrome of Garden City near Antwerp even reopened their doors in July 1915 after closing since the outbreak of the war.[29]

An important issue was the political position of the cycling union, as most of the board members were conservative nationalists. After the reconstruction, most of the velodromes started to reopen their doors during early Spring 1915. At the same time, an important meeting was organized in the head office of the cycling union LVB-BWB in Brussels. Out of nationalistic persuasion and as a symbolic rebellion against the German occupation, they decided that all cycling races had to be cancelled. In other sports like football the unions had similar ideas. Of course, this decision resulted in a lot of turmoil. Several parties feared losing their biggest source of revenue, the velodromes by loss of entrance fees and the athletes by loss of prize money, while, in addition, the union requested all members (organizers and athletes) to pay their license fee for 1915 for administrative purposes. Finally, union members budged on their decisions on the condition that a part of the entrance fees would be donated to charity. In addition, they had to admit that due to the mobility restrictions the union could not send any representatives to weekly events. Consequently, the cycling union could not function as before and, although cycling races kept ongoing as local events, nationally organized competitions came to a standstill.

We also must consider the fact that most of this part of the study is based upon sports articles in newspapers. Next to the fact that the press is not always the most reliable resource we know that the existing newspapers were censured, and that collaborative newspapers were sponsored by the Germans. Sport events and sports articles in the newspapers were tolerated because they were harmless for the regime, it kept the locals quiet and gave them the impression that normal life went on. But as paper became too expensive most of the newspapers were forced to decrease in size, and others simply disappeared. Consequently, writing space was reserved for more important issues and sports articles were the first to decrease or to disappear as well. The decreasing sports articles gave the wrong impression that the sports activities were disappearing. Also, Stijn Streuvels mentioned in his book that ‘For those who have no passport cycling is prohibited – thus also the races – Tour of Belgium etc.[30] Streuvels simply could not have known that cycling had died because there were no velodromes in the neighbourhood where he lived, and he also could not cross municipally borders. So, his statement is clearly based upon personal interpretation and hearsay.

Conclusions

German restrictions did have a significant negative impact upon personal mobility, sports and leisure activities and the transfer of sports information. Federations and unions could not function anymore, and they lost their overall objective to lead and assist their local associations, the clubs, competitions and events. Consequently, cycling competition was reduced to local events with the participation of local athletes. Indeed, from 1916 cycling races saw a downturn, or at least gave that impression, but did certainly not disappear. Sports events just went on during the Great War, including cycling races. As with ordinary life, they were replaced, or the concept changed, some velodromes were demolished while others reopened their doors.

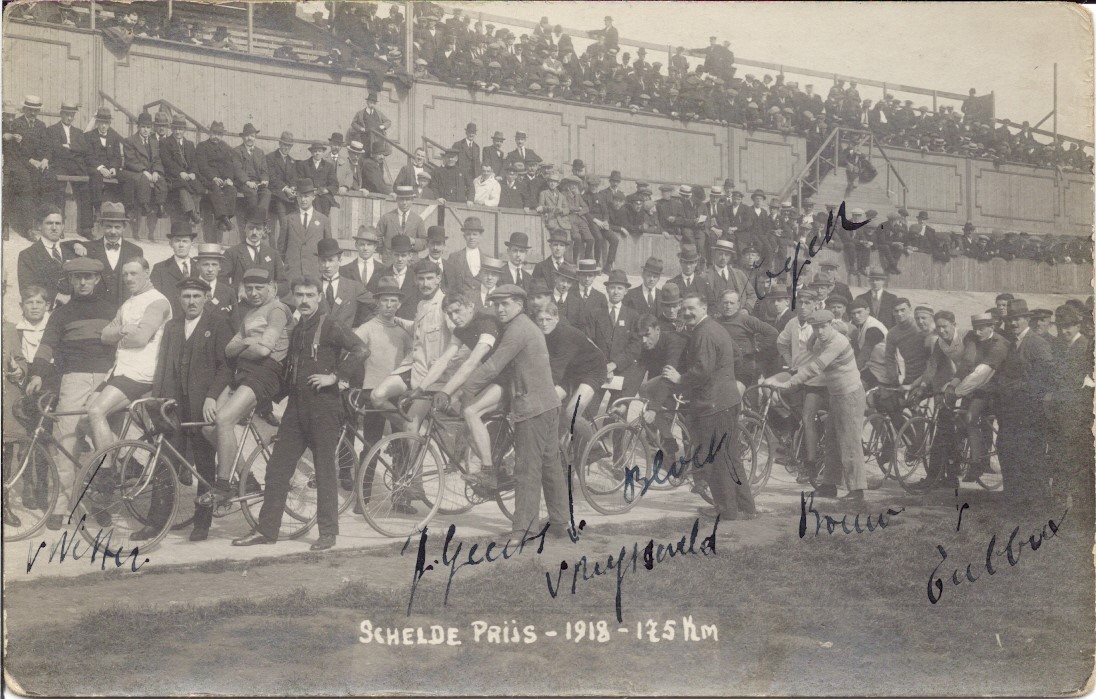

Figure. 3. The Groote Scheldeprijs of September 29, 1918 organized in the Garden City velodrome of Wilrijk near Antwerp.

Even when the German army was forced to retreat in the autumn of 1918 and the Western front moved further Eastwards into Belgium, sports events just went on. On Sunday 29 September in the velodrome of Garden City the oldest Belgian classic, the Groote Scheldeprijs, was organized over 175 kilometres and in the velodrome of Gentbrugge several sporting events like athletic and cycling races, and football matches, were played halfway through October 1918. Another point of view was found in the press after the Armistice of November 11, 1918:

Concerning cycling, motor and car driving, the three sports have done a great job during the War at all levels: as a post service, supply of food and ammunition, etc. In brief, the War did not kill the sports as sometimes is asserted but has even caused the expansion of it. We therefore want to inform our readers that we, just like before the war, will continue to provide articles of all sporting events.[31]

References

[1] Het Nieuws van den Dag, August 2, 1914.

[2] Het Handelsblad, July 29, 1914; August 1, 1914; Het Nieuws van den Dag, August 4, 1914.

[3] Het Vlaamsche Nieuws, November 25, 1914; LDH, November 28, 1918.

[4] Sportwereld, August 3, 1914.

[5] Sebastiaan Vandenbogaerde, Een kijk op de administratiefrechterlijke organisatie van het Etappengebied tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog (Ma. Dissertation: UGhent, 2010), 32-34.

[6] Ibid., 48.

[7] Ibid., 49.

[8] Sebastiaan Vandenbogaerde, Een kijk op de administratiefrechterlijke organisatie van het Etappengebied tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog (Ma. Dissertation: UGhent, 2010), 81-84

[9] Het Volk, April 7, 1915

[10] Stijn Streuvels, In Oorlogstijd. Het volledige dagboek van de Eerste Wereldoorlog, (Brugge/Nijmegen: Orion/B. Gottmer, 1979), 485.

[11] HLN, April 7, 1911; Het Nieuws van den Dag, April 8, 1911; GVA, April 10, 1911

[12] De Vlaamsche Post, October 6, 1915; Gazet van Brussel, October 3, 1915; Het Volk, October 1, 1915.

[13] Regulation poster in the Ortz-Kommandatur Aalst, October 21, 1918; Het Volk, October 21, 1915; De Vlaamsche Post, February 13, 1916

[14] Het Volk, July 25, 1916; Vooruit, July 13, 1916; July 20, 1916; July 25, 1916

[15] Achiel Van Den Broeck and Berten Lafosse, Zo was … Karel Van Wijnendaele, (Kortrijk: Atlas, 1962), 23-25

[16] Ibid., 26

[17] De Gentenaar, August 17, 1915; Le Quotidien, September 23, 1915

[18] Het Volk, July 27, 1916

[19] Het Vlaamsche Nieuws, October 18, 1916; October 28, 1916

[20] Patrick Cornillie, Koersen in de Groote Oorlog, (Tielt: Lannoo NV, 2018), 108-109, 168

[21] Gazet van Brussel, June 29, 1918

[22] Gazet van Brussel, July 22, 1916; HLN, December 1, 1918; Het Nieuws van den Dag, November 28, 1918

[23] Patrick Cornillie, Koersen in de Groote Oorlog, (Tielt: Lannoo NV, 2018), 64

[24] Ibid., 30-32

[25] Ibid., 80

[26] Els de Witte, Dirk Luyten and Alain Meynen, Politieke geschiedenis van België: van 1830 tot heden (Antwerpen: Manteau, 2016), 166-167

[27] Giselle Nath, Stad in de storm. Arbeidersvrouwen en het hongerjaar 1916. (Gent: Handelingen der Maatschappij voor Geschiedenis en Oudheidkunde te Gent, 2011), 213.

[28] Mail by Donald Buyze, April 10, 2019.

[29] Echo de la Presse, July 25, 1915.

[30] Stijn Streuvels, In Oorlogstijd. Het volledige dagboek van de Eerste Wereldoorlog, (Brugge/Nijmegen: Orion/B. Gottmer, 1979), 484

[31] Het Nieuws van de Dag, November 27, 1918.