For Part 1 of this series see – bit.ly/2Gwr9WA and for Part 2 – bit.ly/2DBPsBF

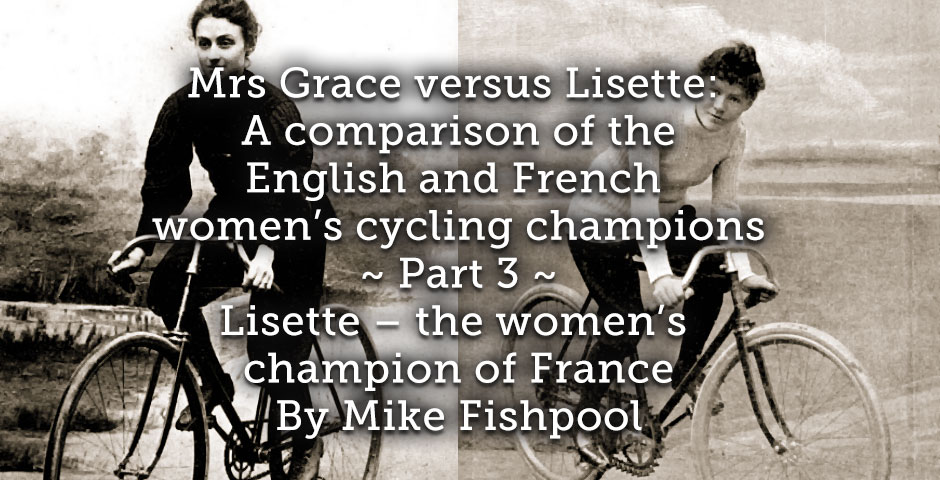

The French newspaper Le Petite Parisien once said: “We shall find that Mademoiselle Lisette is of very small stature, with a solid frame, and a robust leg of masculine look, with a look of energy and strength”. She became a worldwide cycling sensation, often being showered with gifts from admiring spectators attending her cycle races, was regularly featured in newspaper and journal articles, and raced in London, France, Belgium and Switzerland eventually finishing her cycling career in the United States

-

Lisette pictured wearing the sash that she was awarded after her race at Longchamp on 26 August 1894.

Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF).

Amid much contradictory narratives at the time, some key details emerge on her: Lisette’s real name was Amélie Le Gall, that she hailed from Quintin in the Côtes-du-Nord department of northern Brittany, was the daughter of a carpenter and later moved to Puteaux in the western suburbs of Paris. Further genealogical research by this author has led to the discovery that she may have actually been born with the Christian name Marie, sharing it with her mother and one of her sisters, while the spelling ‘Le Gall’ was slightly different in archived censuses. Marie was born in 1869 in Quintin, the youngest child of six children (five daughters, one son) belonging to Louis Le Gal, a carpenter and log-cutter. In about 1882, that entire family moved from Quintin to Puteaux. With another sister and mother sharing the same name, perhaps she had been nicknamed Amélie for most of her life, adopting it officially once she reached adulthood. At the age of 22 in the 1891 Puteaux population census, Amélie was working as a ‘daily labourer’, living with a woman named Josephine, who also had a young son and was one of the daughters from the same Quintin family detailed above, making it likely that Josephine was her older sister – thus supporting the surmise that Amélie and Marie were the same person. Nevertheless, Amélie shortly met and married a Swiss national named Emile Christinet also living and working in Puteaux. The couple moved into a rented property in the Rue des Carrières in Puteaux at least by 1894. Born in 1849, Emile Christinet was listed as a ‘clerk’ in the 1891 Puteaux census, but later stated that he was an ‘electrical engineer’ after making an application to join the French Touring Club in 1896.

According to profiles in several American newspapers, Amélie’s route into cycling came after she was advised to take to the wheel in about 1891 to recover from anaemia, developed due to working in a poorly-lit factory from the age of 14. By 1893, she was regularly riding 100-km endurance rides, eventually racing using the nom-de-guerre Lisette and briefly also ‘Lisette Marton’, perhaps influenced by the theatre; Lisette was a common name in French plays during the 19th Century, usually for the character of a maid. She was actually initially connected to the Parisian theatre, representing the Théâtre de Cluny in her first races, at a time when the racing in Paris featured women employed in the theatre, including dancers, singers and actresses.

-

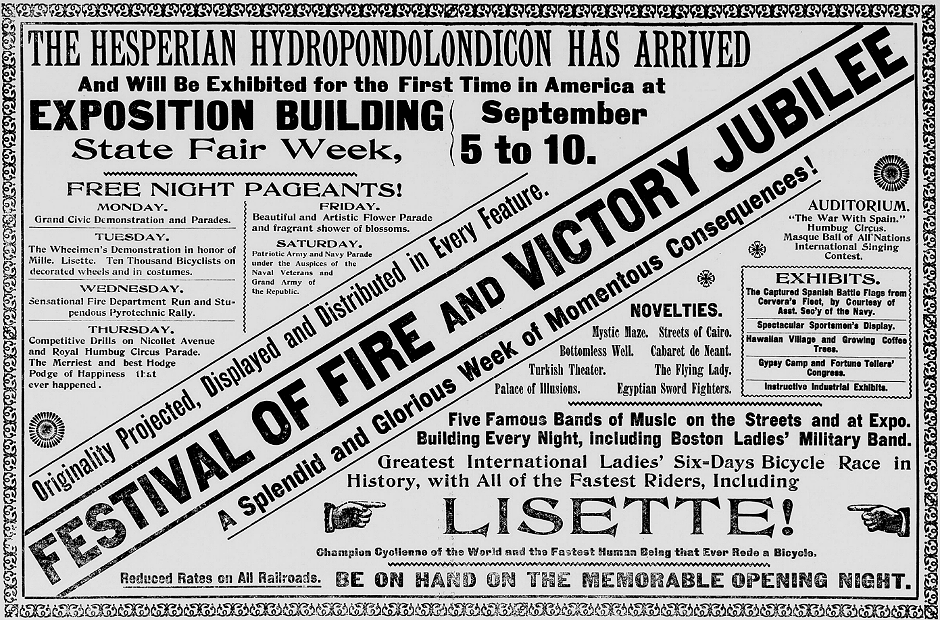

Lisette pictured far-left at her first major race at Cabourg in August 1894.

It can be assumed that the portly hatted gentleman holding her bicycle is Emile Christinet.

Source via Dag Hammar.

Lisette raced publicly for the first time during the summer of 1894, including a two-kilometre women’s race at Courbevoie, Paris in July and a 20-km road race during a cycling carnival held in Cabourg, Normandy in August where she finished second to Hélène Dutrieux. On 26 August, she gained stature that enabled a professional cycle racing career when she participated in a 100-km men’s race at the Longchamp racecourse in Bois de Boulogne, Paris, finishing in eighth position just eleven minutes behind the male winner, and was crowned the women’s champion of France. The feat was repeated again at the same venue the following year in October 1895, this time beating several other female competitors who had also entered. Among some of her notable wins, Lisette emerged victorious in a six-day race at the Royal Aquarium in April 1896, having been the star attraction for the first race at the same venue the previous November where she finished second. Lisette also won an eight-day international women’s race at the Vélodrome d’Hiver in May 1896 and claimed a new paced women’s hour record at the Vélodrome Buffalo in Paris in September.

Lisette was one of the few female racers of the 1890s to go up against men. Following the 1894 Longchamp race, she participated in a men’s track race in July 1895 at the Vélodrome de Varembé in Geneva, Switzerland and was pitted against Choppy Warburton’s male track star Jimmy Michael in February 1896 at the Vélodrome d’Hiver followed by Albert Champion several times in 1897 – taking the top billing on the final day of a six-day women’s race at the Royal Aquarium in January that year and again at the Vélodrome d’Hiver in March (the one occasion that Lisette was victorious in a one-on-one race with a male cyclist, even though she had a head start). In one interview, she said that the similarities in her riding style to the Welsh champion Jimmy Michael led Choppy Warburton to nickname her ‘La Sœur de Michael’ (the sister of Michael). They were also of a similar height with Lisette standing slightly shorter than the five-foot, one and half inch Michael.

-

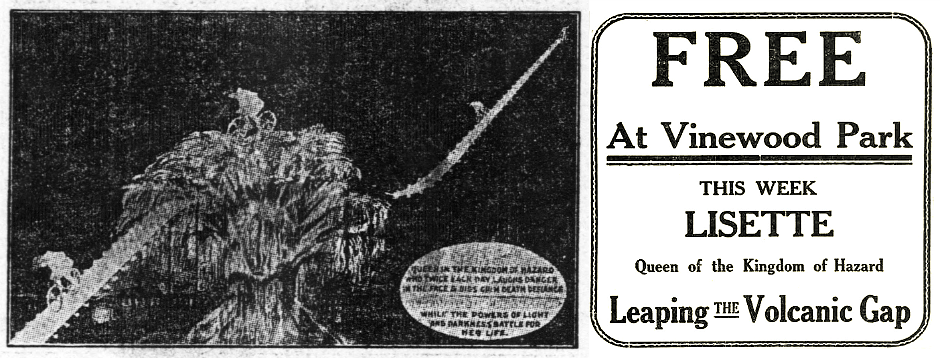

Lisette was the star billing for the Festival of Fire and Victory Jubilee held in Minneapolis in September 1898.

Source: US Library of Congress.

After undertaking her last domestic races in Calais in July 1898 and nearly a year after Choppy Warburton’s sudden death, Lisette moved to the US the following month, initially moving to Minneapolis where she was top of the bill for a women’s race at the Festival of Fire and Victory Jubilee held in the city in September. She was beaten by the Swede Tillie Anderson, who would become one of her major rivals in the US. Lisette continued racing until 1901, before performing daring cycling stunts called the ‘Volcanic Gap’ and the ‘Cycling Dazzle’ at carnivals and fetes in the US until about 1908. After finally retiring from cycling altogether and calling herself ‘Lisette Christinet’, she switched to the restaurant trade in 1910, running various establishments with Emile (who died in 1918) in parts of south-eastern US until the early 1920s.

-

An illustration of Lisette’s Volcanic Gap ramp-to-ramp cycling jump and an advert publicising an appearance at Vinewood Park in Topeka, Kansas.

Source: US Library of Congress.

Article © Mike Fishpool

Thanks Mick for your research, I am more interested in the acrobats of the world for the Walls of Death, the Globes, and the Infernal Bins, trampines of acrobatic numbers outside and in the room. Now I know more about “Lisette” thanks to you

Hi Lilas. Many thanks for your comments. Might be worth looking at Lisette’s French rivals Hélène Dutrieux and Mlle Aboukaïa who both turned to acrobatics after retiring from cycle racing with Dutrieux doing loop-the-loop on a bicycle where she was known as the ‘Flèche Humaine’ while Aboukaïa performed a stunt known as the ‘Comete Vivante’ (Living Comet) where she would throw herself off a tower attached by a wire, slide down a ramp on her belly, and land on a safety net. Both women also flirted with motorcar stunts but became more famous as pioneering aviation heroines about 1910-1913. There was also the American rider Dottie Farnsworth who performed the ‘cycling whirl’, possibly similar to a helter-skelter ride, but died in 1902 of blood poisoning from injuries sustained from an accident whilst performing. A few British riders briefly also had a go at cycling acrobatics but it wasn’t as much as draw as it was for the French riders.

Hélène Dutrieux was born in Belgium by the way.