The Women’s Amateur Rowing Association (WARA) has attracted little academic attention, yet as the first governing body to legislate for women’s rowing, its formation, ideology and development merit further examination. The WARA was formed in 1923 with the following goals in mind:

- To maintain amongst women the standard of Oarsmanship as recognised by Amateur Rowing Clubs;

- To hold a Regatta or Regattas if and when so determined by the Committee, such Regattas to be mainly or exclusively for women;

- To promote the interests of Boat Racing generally amongst women.

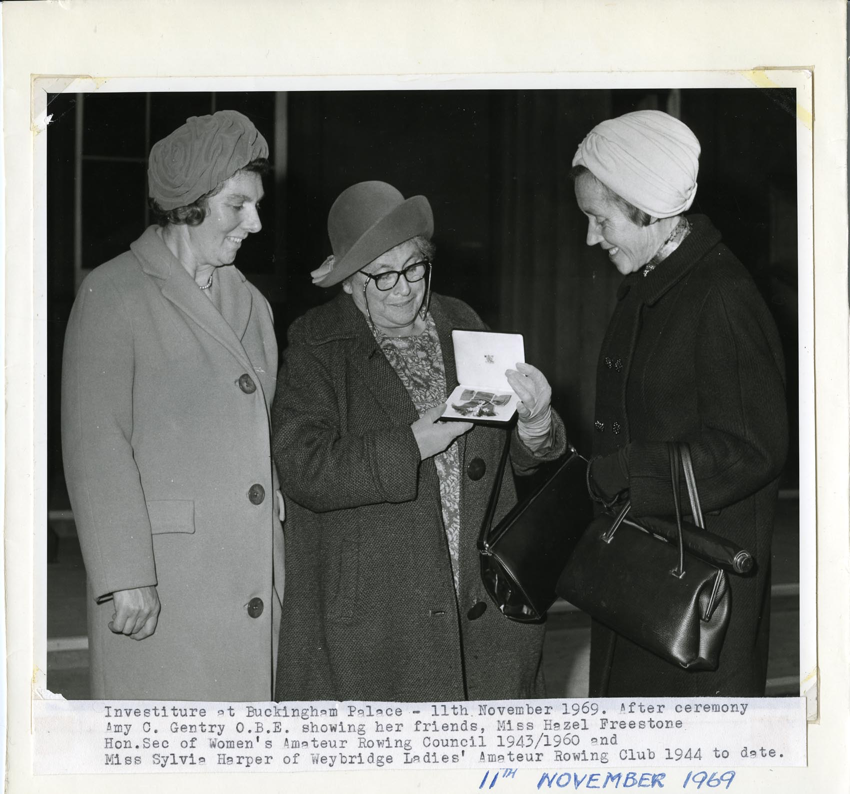

The WARA is frequently connected to Amy Gentry, a successful athlete in the 1920s, an almost lifelong administrator of the sport, founder of Weybridge Ladies Amateur Rowing Club (WLARC) and well-known rowing personality along the banks of the River Thames. Undoubtedly, Gentry played a huge role in developing the sport, and the WARA. She sat on the committee for almost all of its forty-year history, before it was amalgamated into the Amateur Rowing Association (ARA) in 1963, as Assistant Honorary Secretary, Honorary Secretary and, latterly, Chair. Her active involvement in the sport and its administration is easily observable in archive materials and personal accounts, and indeed her award of an OBE in 1969 for her contribution to rowing.

- Image- Amy Gentry, on receiving her OBE (© River & Rowing Museum, Henley on Thames)

Yet she was not responsible for its foundation. This is acknowledged in some historical accounts (notably by Schweinbenz), which name ‘Mrs K. L. Summerton’ as the founder, and Gentry having been brought on to the WARA committee in its early stages as her assistant. The use of her initials only indicates the limited information available in rowing records; indeed, without undertaking genealogical research to identify her even her full name would have remained unknown.

This research identified ‘Mrs K. L. Summerton’ as having been born in 1875, as Kate Louise Parrish. She was born in Essex to Isaac and Caroline Parrish; her father was a general labourer, and by the age of sixteen, she was employed in general domestic service in a neighbouring town. There is no evidence of her level of education. Her birth date is such that she turned five in 1880, in the same year schooling was made compulsory between the ages of five and ten, under the 1880 Education Act – yet as take-up of this Act was uneven, especially in working-class households, this is no firm indicator.

Between 1891 and 1901, Kate Parrish got married, had a child, and moved to Camberwell in south London. (Little is known about her husband, John Summerton; he was born in Lancashire in 1871, and according to the 1901 census, he was then employed as a gold blocker.) Despite having had a child, however, Summerton did not spend much of her adult life as a mother: the baby died before it reached the age of one.

Mentions of Summerton as a rower herself are very sparse. She was forty-eight when the WARA was formed in 1923, and it is unclear how long she had been involved in the sport by this point. She was captain of her club, Helen Smith Rowing Club, in 1923, which suggests her involvement went back a couple of years at least, and that she was (or had been) a practising rower: she was not just an administrative figurehead. Helen Smith RC was in Barnes, based at Tom Green’s Boat House (a sporting institution on this stretch of river, home to a number of men’s and women’s clubs). Helen Smith is referenced in the minutes of the WARA until 1937, but there is no evidence as yet of a founding date, or of any activity after World War Two.

- Image- Rowers from an unknown club leaving Green’s Boat House for the river, c.1930 (© River & Rowing Museum, Henley on Thames)

Little is recorded in terms of Summerton’s views on rowing, or her sporting ideology. An article in the Manchester Guardian from 1926, however, offers some commentary. It is claimed she ‘is not only concerned with competitive work and raising the technical standard’, but that ‘she wants to make rowing more enjoyable for all women who care about it’. Beyond this, ‘she has been teaching some of the older members of her own club how to manage their boats’ – women who ‘like to go for joy rows with their friends, but do not want to put other river craft in peril’. Her focus here is on enjoyment, whether in competition or in ‘joy rows’, but health is also important: it is claimed that if female rowers ‘take care of themselves[…] their exercise does them an immense amount of good’. The article also addresses questions of style and strain, the latter in particular a regularly voiced anxiety with regard to women’s participation in sport. The WARA, it claims, ‘is anxious that its members should not overstrain themselves’, and as a result, that it has ‘introduced the idea of “style” into their rowing’. While women ‘used to huddle themselves up into positions which entailed strain’, they are now encouraged to adopt better posture, skills and technique; and ‘by organising competitions [the WARA] is encouraging the women and girls to take their work more seriously’.

- Image- A WLARC crew (including Amy Gentry) in Putney, ready to race in 1927 (© River & Rowing Museum, Henley on Thames)

Summerton only spent four years on the WARA committee, and no direct communication from her about leaving the committee is available. In committee meeting minutes, Gentry reports that ‘Mrs Summerton had asked her to carry on as she herself was too unwell to do so for the present’, and about a year later, in March 1928, the committee ‘unanimously’ agrees to invite her to be an Honorary Vice President. No response is recorded. In a retrospective written by Gentry for Rowing magazine in 1949, this chain of events is framed slightly differently. She claims that she ‘took over her duties’ since ‘the heavy work involved, coupled with having to care for an invalid husband, was too much for Mrs. Summerton’s health’: the hard work of rowing administration is emphasised, as is domestic responsibility. Summerton’s withdrawal from the committee takes place in the shadows, and ‘off the record’; her decision is mediated through Amy Gentry – a woman with a significant stake in the organisation and its future, and a strong influence on its narrative legacy.

The WARA is characterised in the (albeit limited) literature as a female reflection of the ARA, aiming to replicate its conservative and exclusionary approach to class, and its extreme construction of amateur ideology. At a structural level, the idea of a governing body – of formalised rules, of competition within a closed circle of clubs – tends to be aligned with a social context to which Summerton appears to have had no exposure. There is an unlikeliness to her foundation and early leadership of the WARA, and this unlikeliness has perhaps compromised her place in the sport’s history. Her biography, and this unlikeliness, raise important questions about the initial purpose and character of the WARA – and, indeed, other communities of amateur sportswomen. This forgotten founder demands a more nuanced, and more problematised, analytical approach to the early women’s sport.

No photograph of Mrs K. L. Summerton has yet been identified, if you can help Lisa with her quest please leave a comment for her via this article.

Article © Lisa Taylor