This Playing Pasts article is the English version of a longer Italian article (2018), that can read here: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/iulitera/issue/41293/499027

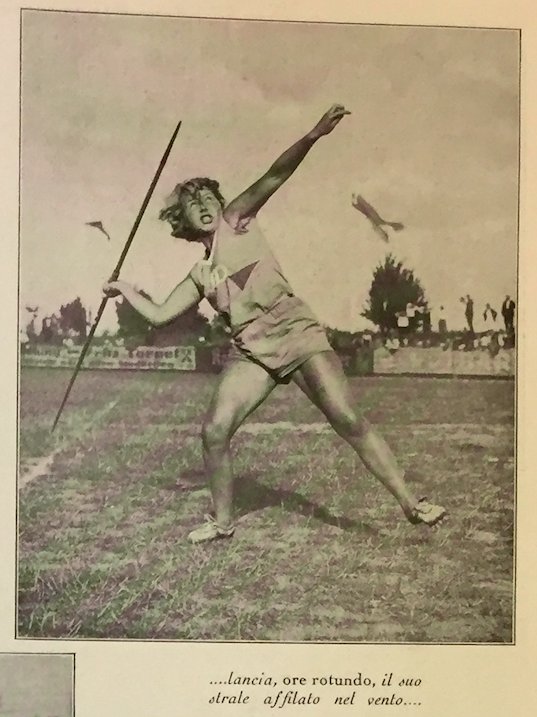

Women’s sport was quite controversial in 1930s’ Fascist Italy. On the one hand, the regime promoted it: as Mussolini said in his famous Discorso dell’Ascensione (1927), demography was the key to the Empire. Italy could not have any economical growth or go to war without a demographical increase (on that occasion he said, ‘if our population decreases, we will never become an Empire, but a colony’). For this reason, the Fascist regime promoted physical education in Italian schools, and all forms of female sport: healthier females would in time become healthier mothers, who would one day give birth to Mussolini’s future soldiers. Then, after the 1932 Olympic Summer Games (where top of the medal tally was the USA, thanks in the most part to the outstanding performances of their sportswomen), Fascist Italy had one further reason for promoting women’s sports: during the next Games (Berlin 1936), Italy would win more medals, thanks to its female athletes. For this reason, from 1933, there was an increase in the promotion of female sports, especially Olympics sports such as athletics and swimming.

Yet a large part of Italian society, led by conservative Catholics, protested at such innovative activities and (public) competitions, where the audience would be able to watch young female athletes and swimmers in shorts and swimsuits. In 1933, a big controversy broke out between Il Littoriale (sports newspaper and mouthpiece of Fascist sports policy) and L’Osservatore Romano (Vatican newspaper) about the ‘immoral’ women’s sportswear (see https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/uncategorised/all-about-that-skirt-womens-sportswear-in-1920-1940s-fascist-italy-part-1/ ).

The Italian controversy had some pan-European features, such as the role of Hollywood divas as femlae sport models, but also specific ones, related to the Italian society in which it was taking place: what about the use of Classical (both mythological and historical) women, such as Cloelia, the Amazons, Atalanta, Nausicaa, used as archetypical figures of sportswomen?

The sporting woman

Source: Almanacco di Cordelia 1930, p. 129

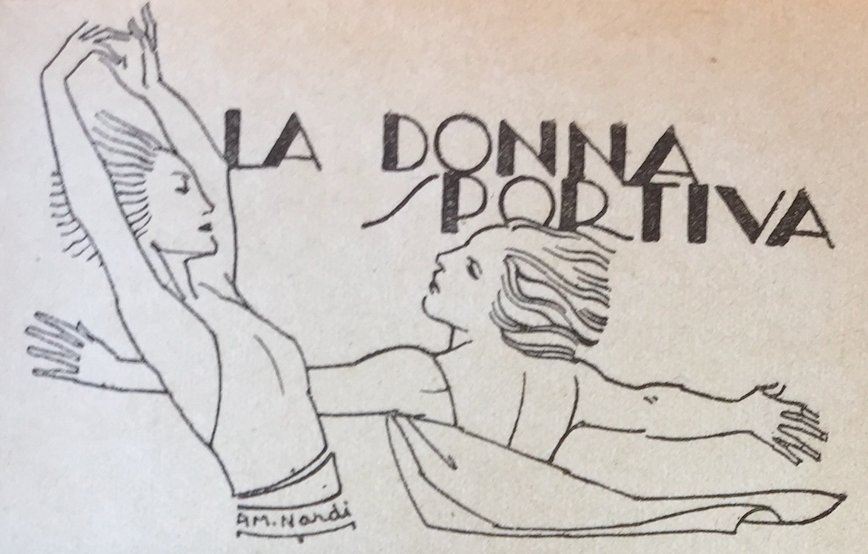

At that time, the Classical culture was still had a big role in Italian culture: the best high-school students attended Liceo Classico, the ‘Classical High School’ where they studied Greek and Latin Literature & Language, and that was the only high school that gave access to all university courses. The up-coming doctors, lawyers, politicians, engineers were all filled with Classical Arts, History, and … myths: if a journalist referred to one of them, every reader would understand it. On the other hand, Classical myths had a lot of popular versions: not only children’s books but also visual arts, advertising, popular press, so that even the less well educated could understand for example a reference to Prometheus, Arachne, Echo, Narcissus. During the Fascist regime, there was massive exploitation of Roman History, for nationalistic reasons: every schoolboy (and schoolgirl, too…) was taught to know and to praise the courage of Mucius Scaevola, the Roman soldier who thrust his right hand into a fire to prove his braveness to Rome’s enemies.

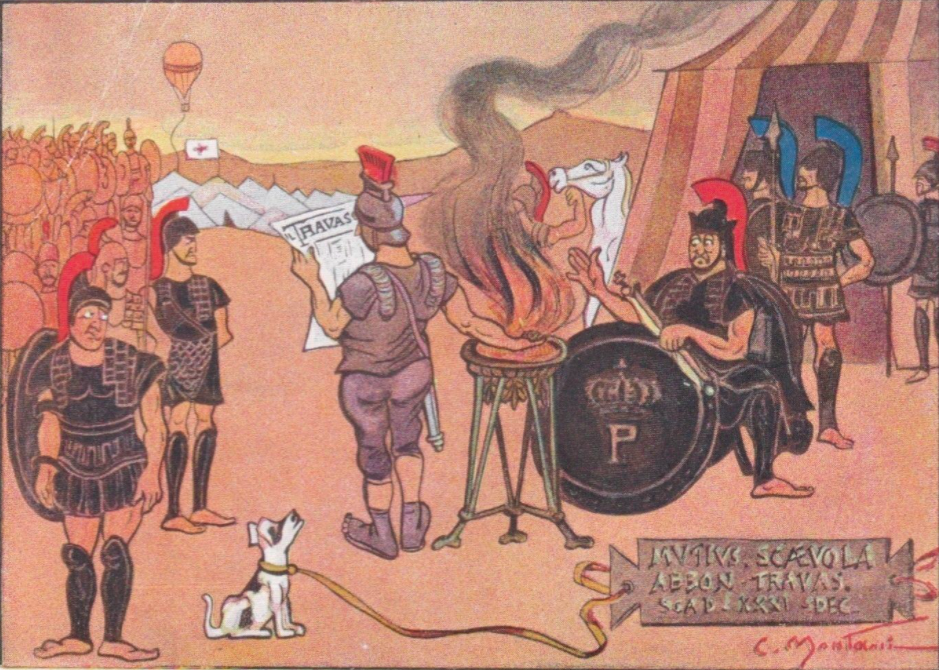

A 1929 print about Scaevola’s sacrifice

The caption quotes his words: ‘Watch how the Roman despise the value of their own life’

Source: https://bit.ly/3kStQWD .

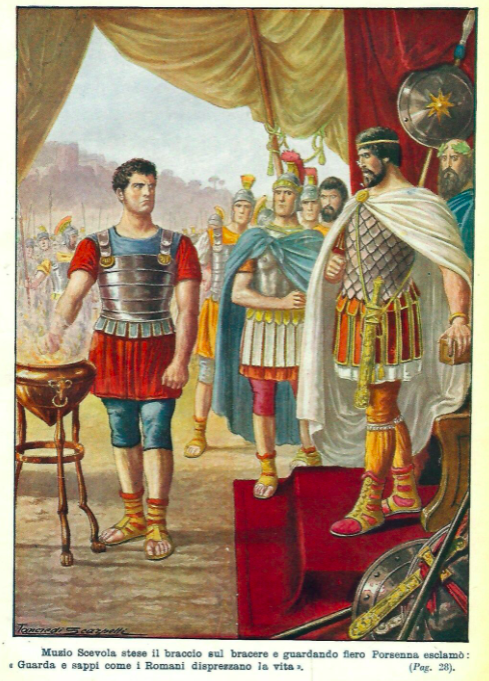

A postcard about Scaevola’s sacrifice: on the upper part, a mark by Figli del Littorio, a Fascist Youth association

Source: https://bit.ly/3BHf9fO .

The simple use of these Classical references by the satirical press shows that everyone in Italy could understand such myths and ancient history man … and women.

In this postcard by the satirical magazine Il Travaso delle Idee, Mucius Scaevola is so focused on reading the magazine during his sacrifice in front of Etruscan king Porsena (see the ‘P’ letter) that he didn’t mind the heat of the fire …

Source: Il Travaso delle Idee, https://bit.ly/3zNhKoa

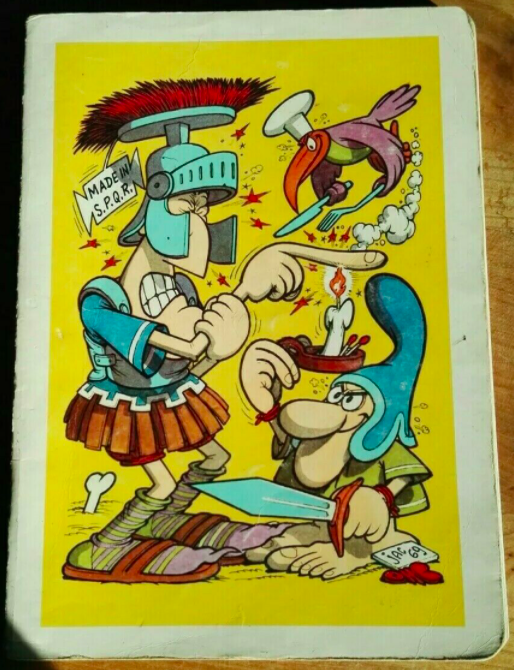

The Classical heritage went on even after WW2, but it began to be criticized, after the long abuse by the Fascist regime

In this 1960s’ cover of a school notebook, the famous childrens’ literature illustrator Jacovitti criticized Mucius Scaevola

on the back, he writes that, in order to save his skin, the Roma soldier sacrificed only his finger …

Source: https://bit.ly/3h0Nles

So during the several controversies of the Interwar period regarding women’s sports Classical figures where often used. Let’s start from the common language: female swimmers were often called ondine (singular ondina), while Eva sportiva was a popular expression used to talk about sportswomen, because since Biblical Eve was the archetypical model for every woman. For the same reasons, Venere in cielo ‘Venus in the sky’ meant ‘female aviator’ or ‘female parachutist’.

“nuotatori ed ondine”

Source: Il Resto del Carlino, 25/08/1933, p. 4

A rare use of «sirenetta» ‘little mermaid’ used to refer to female swimmers

Source: La Gazzetta Dello Sport, 08/08/1933, p. 2

In this case, Eva in maglietta ‘Eve wearing a shirt’ refers to the female football fans.

Source: La Voce Sportiva, 06/01/1931, p. 3.

A further interesting fact about ondina term is, because female rowing was not that popular in Italy (see https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/articles/gender-and-sport/rowing-under-ponte-vecchio-a-history-of-womens-rowing-in-fascist-1930s-italy-part-1/ ), it could also be used to refer to a ‘rower’. When the title of the German movie Acht Mädels im Boot ‘Eight Girls in a Boat’ (1932) was translated into Italian, it became Il club delle ondine ‘the Undines’ club’, that meant ‘the female rowers’ club’. After all didn’t swimmers and rowers share the same water environment?

A scene from the movie

Source: https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/989571102274932737

Talking about female rowing, we must consider a unique but very interesting occurrence not from the Classical but from Biblical female activity. In a 1933 article published by the Federal review, Mimmo Bombi praises not only the simplicity and modesty of Eve (who didn’t wear make-up in the Garden of Eden), but also the brave spirit of Noah’s wife and three daughters-in-law: in fact, they travel on the Ark, and helped their husbands with the rowing, ‘becoming the first-ever female team in history’. The conclusion of this bizarre text is: ‘So women’s rowing is almost as old as the world itself, and it’s so noble: it was useful to save mankind!’.

Noah’s story in the mosaics of Monreale Duomo, Sicily

There some women in the Ark, but they’re always passive, just watching what men do …

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monreale_Cathedral_mosaics

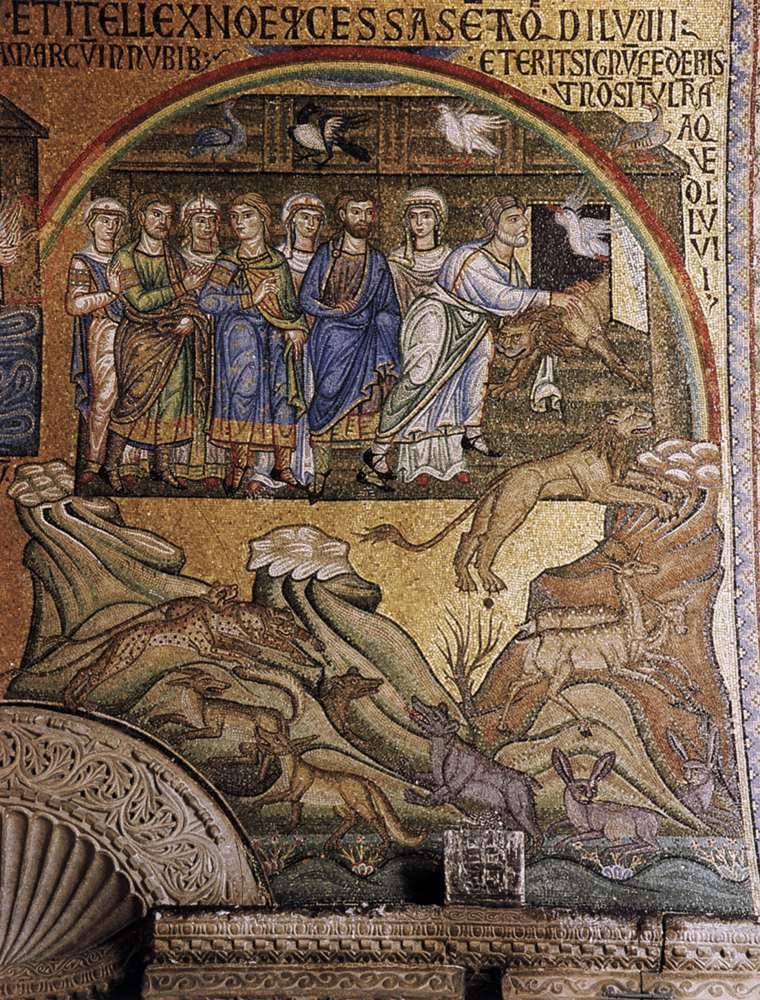

Noah’s story in the mosaics of nartex of St. Mark’s Basilica, Venice

Under the rainbow sign, Noah is letting the animals go out, while his wife and the three couples are watching the scene

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Narthex_of_St._Mark%27s_Basilica_(Venice)?uselang=it

During the L’Osservatore vs. Il Littoriale controversy (November-December 1933), three Classical characters were used by both opponents, those who supported women’s sports (Il Littoriale) and those who asked the Fascist regime for strong limitations on women’s practice, above all the public one. What we should research therefore is not only which female characters were used, but how they were used: since myths are such a rich source for human thought, there were (and are) several ways to utlise these stories.

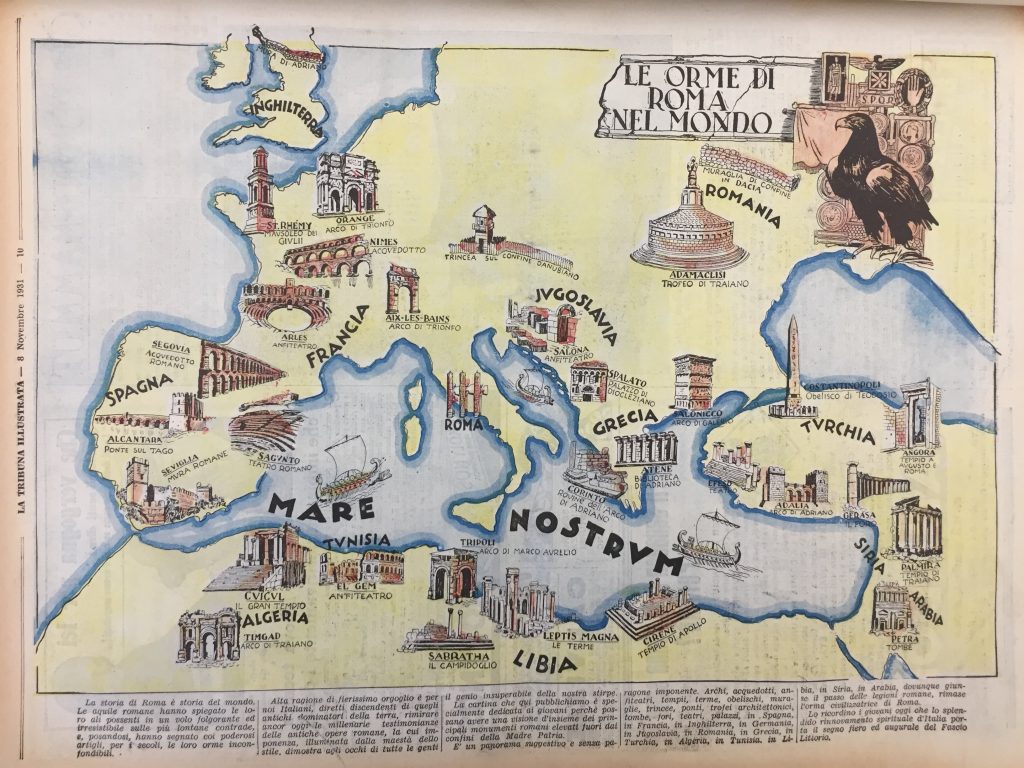

A further example of the Fascist exploitation of the Roman History: a map depicting ‘Roman footprints in the world’

The several monuments outside Italy should prove the young Italians the ancient glory of Italy; on the other hand, the city of Rome wasn’t symbolized by the Colosseum, but by three fasci littori, the symbol of the present regime …

Source: La Tribuna Illustrata, 08/11/1931, p. 10.

The Vatican journalist who started the controversy writing in L’Osservatore Romano in November 1933 opposed the immoral sporting practice of Ancient Greece and the absence in Classical Rome – at that time in Italy, the Roman heritage was more valued than the Greek one. Il Littoriale answered recalling the existence of the Heraean Games (Heraea), held at Olympia every four years in honor of the goddess Hera: they included a footrace for young women. The fact was that even Greeks stopped to organize such a sports event (introduced to bypass the ban of women’s participation at the “real” Olympic Games), which should be recognized as experimental. According to the Il Littoriale journalist, the existence of a nexus between moral crisis and the drop-out of women’s sports in the Ancient world is proved by the story of Cloelia, an example of the braveness of the ancient Roman matronae ‘married mothers’ who gave birth to the up-coming conquerors of the world. Was the Fascist regime willing to make the same error – forgetting the value of the ancient mothers?

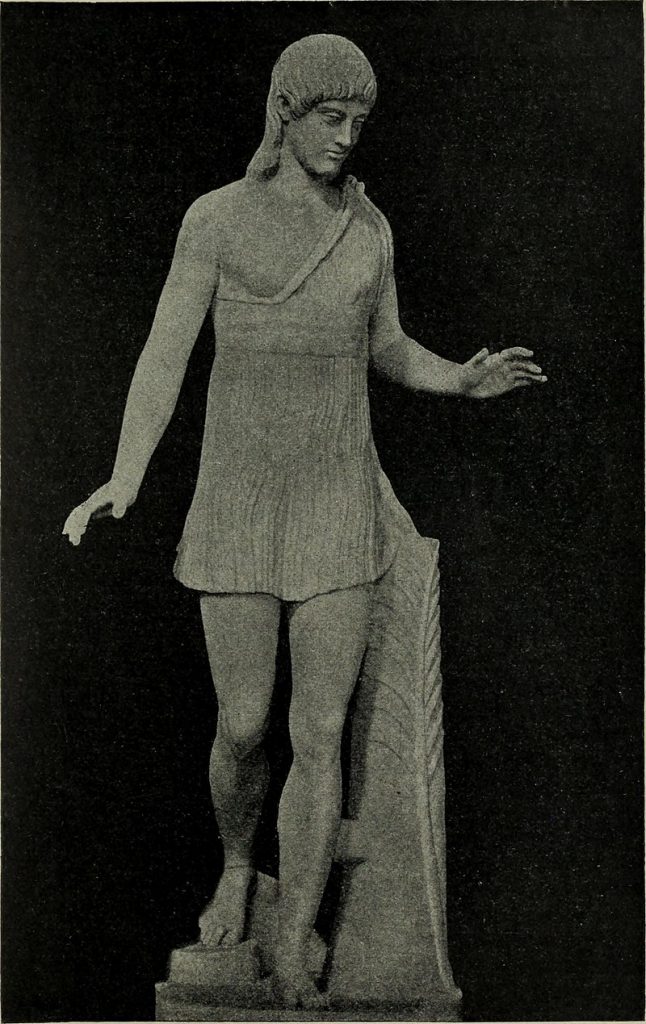

A running girl during the Heraean games

Note the short chiton she wears, and the exposed right breast

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heraean_Games

Cloelia was a quite legendary Ancient Roman female mentioned by the historian Livy. She escaped from her imprisonment with some friends during a war against the Etruscans by swimming across the River Tiber.

Cloelia’s history by Guidoccio di Giovanni Cozzarelli, 1480 (?), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Cloelia was hostage of Etruscan’s king Porsena because it had been established by a Roman-Etruscan treaty that a number of Roman females should been delivered to their enemies

Source: http://www.travelingintuscany.com/art/guidocciocozzarelli.htm

Brave Cloelia convinced her friends to escape from the Etruscan camp and to reach Rome by swimming in the River Tiber

Source: http://www.travelingintuscany.com/art/guidocciocozzarelli.htm

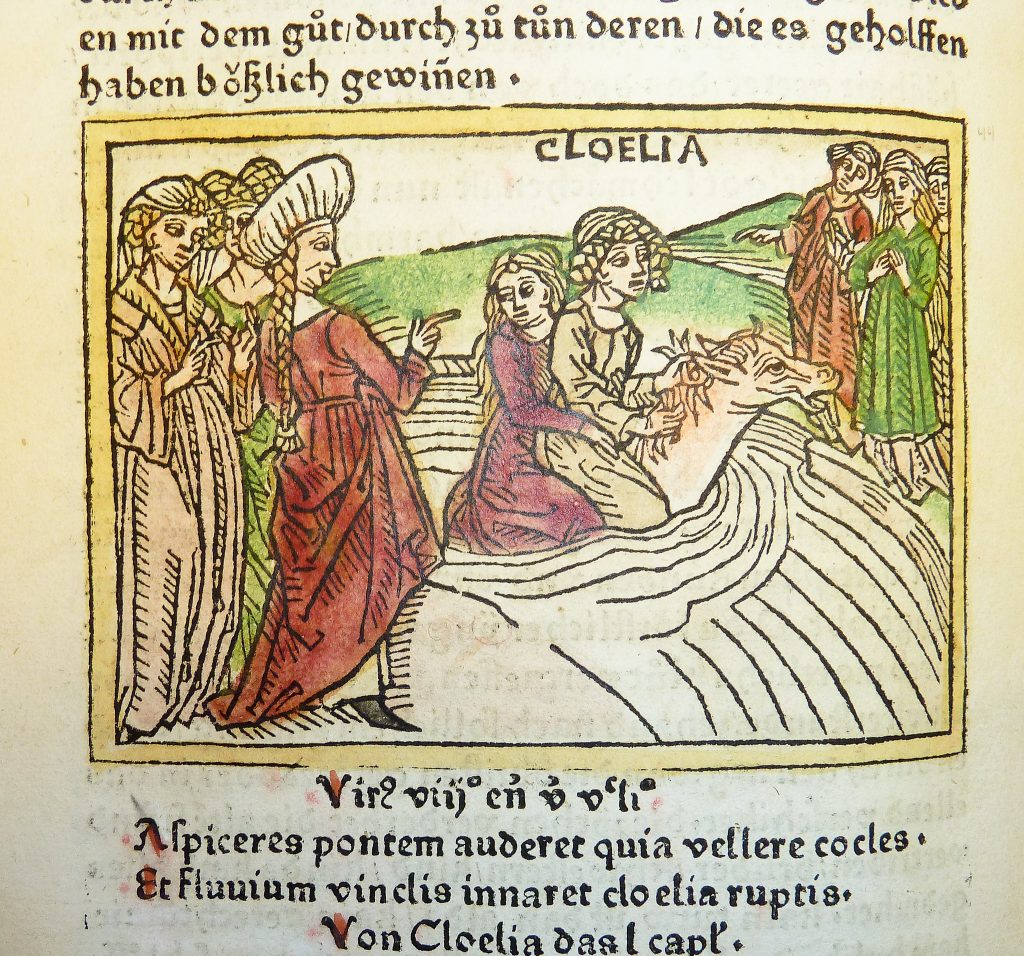

According to another version, Cloelia exploited the fact that the Etruscans led some horses to the Tiber in order to let hem drink the waters

This image is taken from from an incunable German translation by Heinrich Steinhöwel of Giovanni Boccaccio’s De mulieribus claris, printed by Johannes Zainer at Ulm ca. 1474

Source:https://www.flickr.com/photos/58558794@N07/6693273807

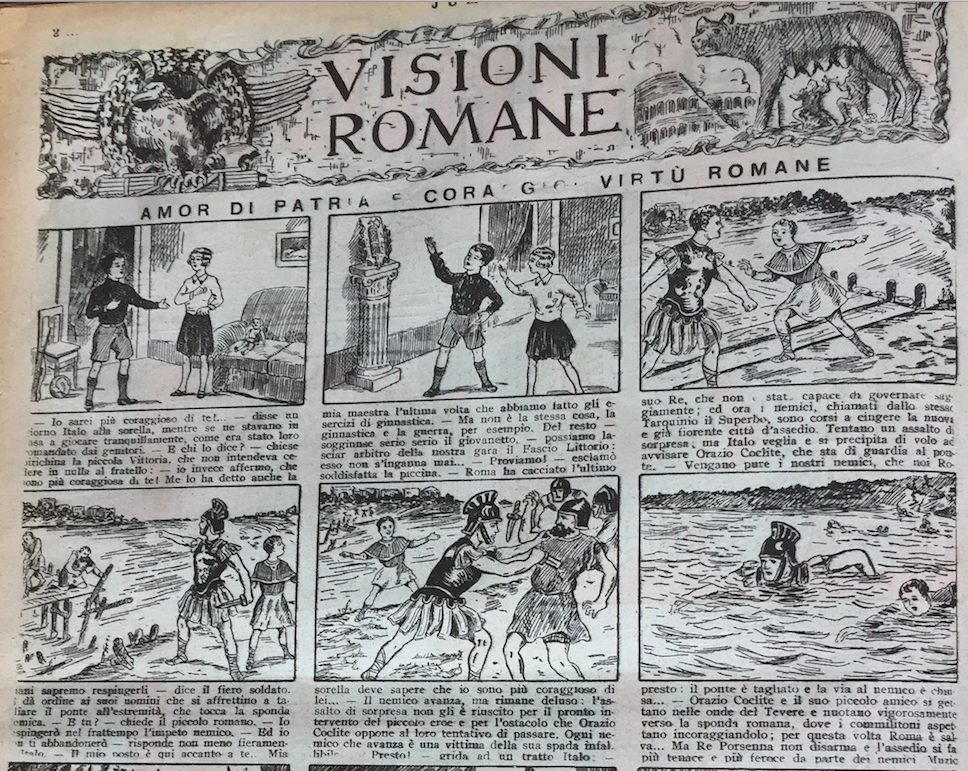

Although Cloelia’s history wasn’t so well-known, it was studied in school, and we can find some very interesting comic strips, published by the childrens magazine Jumbo, called Visioni Romane – Amor di patria e coraggio, virtù romane ‘Roman Visions – Love of country and courage, Roman virtues’. The main character are Italo and Vittoria, two siblings both member of the Youth Fascist association – the first wear the Balilla uniform, her sister the Piccole Italiane one (see https://bit.ly/2Vwtzjc ). In the first speech-balloon, Italo claims to be braver than Vittoria, who suddenldy says: ‘Who says that? I claim that I’m braver than you! That’s what my tole me teacher while we were having our gymnastic lesson …’ ‘Gymnastics is not war! But let our Fascio Littorio decide: it can never be wrong’. The Fascio Littorio, used a sort of magical judge by the two kids, make Italo take a trip through time: he can live an adventure with Roman hero Horatius Cocles, an officer who defended a bridge from the invading army of … king Porsena, of course! After fighting, Horatius and Italo throw themselves into the river, swimming to the Roman side of the Tiber.

The first 6 cartoons of ‘Visioni Romane’

Source: Jumbo, 12/08/1933, p. 2.

Then, Italo had the chance to meet Mucius Scaevola, and to watch his sacrife, learning that ‘in Rome we are this way: ready to die for the freedom of our country’. But what about Vittoria? She’s also in the Etruscan camp, with Cloelia and all the female hostages.

In the third cartoon from left, Clelia is talking to her friends and to little Vittoria, convincing them to return back home: ‘I want to go on fighting for my country’

Source: Jumbo, 12/08/1933, p. 2.

Then a large group of hostages, led by Cloelia, swim across the River Tiber. The Roman Senate wasn’t happy about that, since this was against the treaty, so they are all sent back to Porsena. The Etruscan king marvelled at the hostages’ courage, so that, following a specific request made by Cloelia, he decided to free most of them. Back to the present time, Italo and Vittoria agree: they were both brave, because ‘our motherland is full of heroes and heroines, and we must imitate them’.

In the first cartoon, Vittoria swimming with Cloelia and the female hostages

Source: Jumbo, 12/08/1933, p. 2.

Cloelia was used by Il Littoriale as an example of ancient Italian female virtue (being ancient Rome the ancestor of modern Italy, according to Fascist ideology). Rejecting this historical example, L’Osservatore warned that Il Littoriale should search for a more appropriate role model for the new Italy envisioned by Fascism, based on a Christian model, rather than a pagan one. We might add that Cloelia (later abandoned by the Il Littoriale journalist, as a sort of less powerful weapon) was too masculine a model for that time: acting as a sort of paratrooper, the brave woman takes her decision against the treaty signed by the male Etruscan and Roman leaders; she swims in open water with her young friends; she takes the responsibility to choose which hostages were going to be freed by Porsena. Women’s sports was after all related to war and politics.

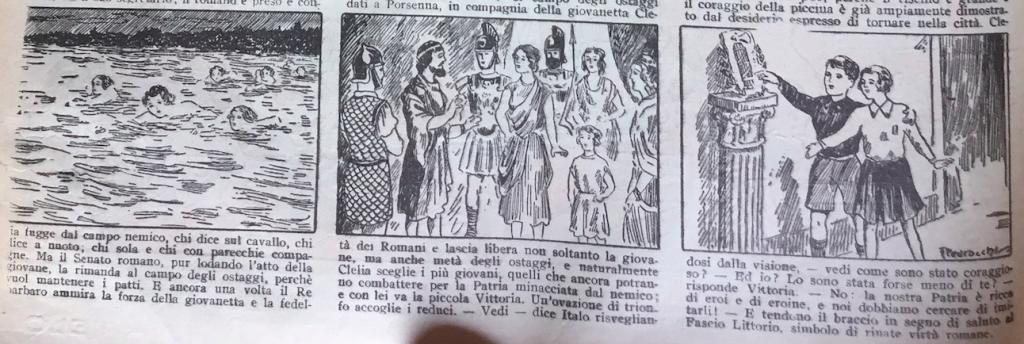

A mounted Amazonian warrior armed with a labrys

Roman mosaic emblema (marble and limestone) from Daphne, second half of the 4th century AD, now at the Louvre, Paris

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amazons

Talking about women, mythology, and war, we must mention the Amazonas, the brave and independent female warriors and hunters who were able to ride and to fight like men, killing all who dare enter their kingdom – no surprises that they were considered “barbarians” by the Greeks! In the 1930s Italian press, they were often linked to the new model of the independent woman of the UK and above all the US, who often were not interested in marriage and childcare. In a 1934 article, the Archibishop of Milan Ildefonso Schuster lashed out against those Italian women who took advantage of WW1 to leave their home and their maternal duties and got a job. According to Schuster, those women who left the traditional good example of Penelope (the faithful wife who had been waiting years for the return of her husband Odysseus) and became new Amazons. Sports were also a feature of these women who divested themselves of their femininity: in order to practice their activities – a lot of them skip Sunday mass!

Cardinal Ildefonso Schuster: he was Archbishop of Milan from 1929 to 1954

Source:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfredo_Ildefonso_Schuster

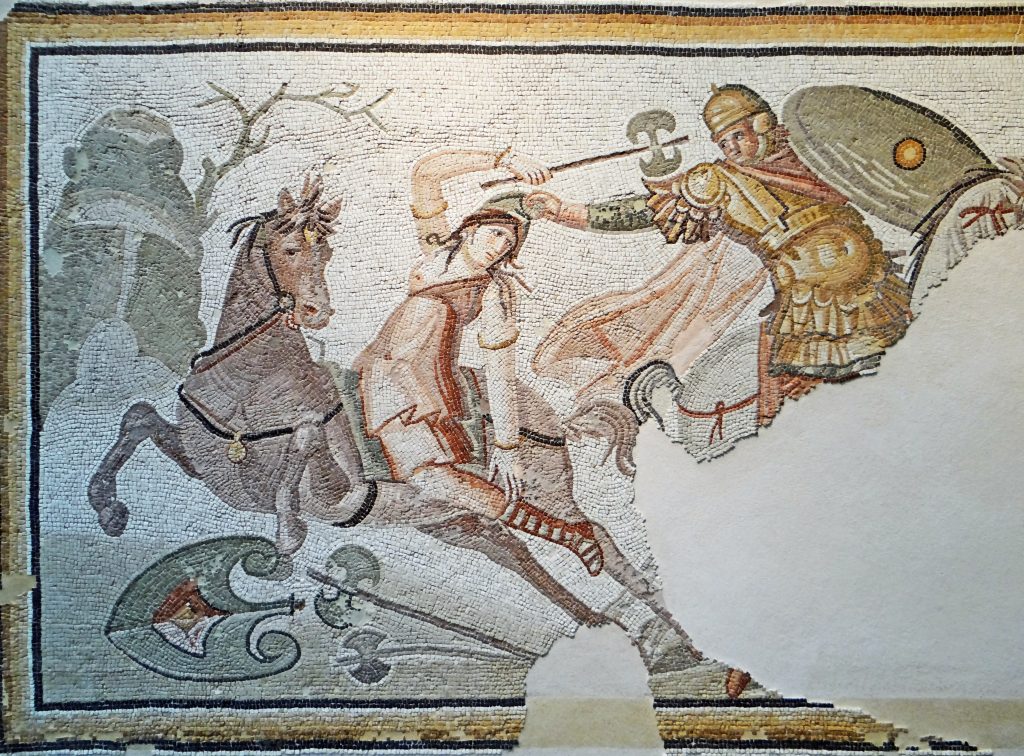

In 1933 journalist Marco Ramperti reminded his L’Illustrazione Italiana’s readers that he was really impressed watching the women’s athletics events during the Summer Olympic Games in Los Angeles – there were no female Italian athletes at these Games. Using not Amazons but rather Bellona, Ramperti writes that those modern women reminded him of the Roman goddess of war, armed with a helmet, which many Western artists have used as symbol of war. In particular, Ramperti was shocked by the US athlete Babe Didrikson-Zaharias and German thrower Ellen Braumüller: the first won many medals wearing (short) clothes similar to the goddess ones; the second threw her javelin laughing like Bellona did.

Statue representing Bellona, at the top of the Des Braves monument, at the entrance of the Des Braves park, in Québec, Quebec, Canada (1863)

Source: https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bellona_(mitologia)?uselang=it

Bellona in the Bertram Mackennal 1916 Gallipoli war memorial, Canberra, Australia

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bellona_(goddess)

The picture in Ramperti’s article: possibly javelin thrower Ellen Braumüller?

Source: L’Illustrazione Italiana, 17/09/1933, p. 423.

Babe Didrikson during the 1932 Olympic Games

Source: https://sport660.wordpress.com/2016/07/15/babe-didrikson-la-campionessa-polivalente-dei-giochi-del-1932/

If Amazons and Bellona were used as negative models: what about the positive ones? Women’s sports supporters had to find them not only in real world, but also in the mythological one, because of the symbolic power of myth in 1930’s Italy.

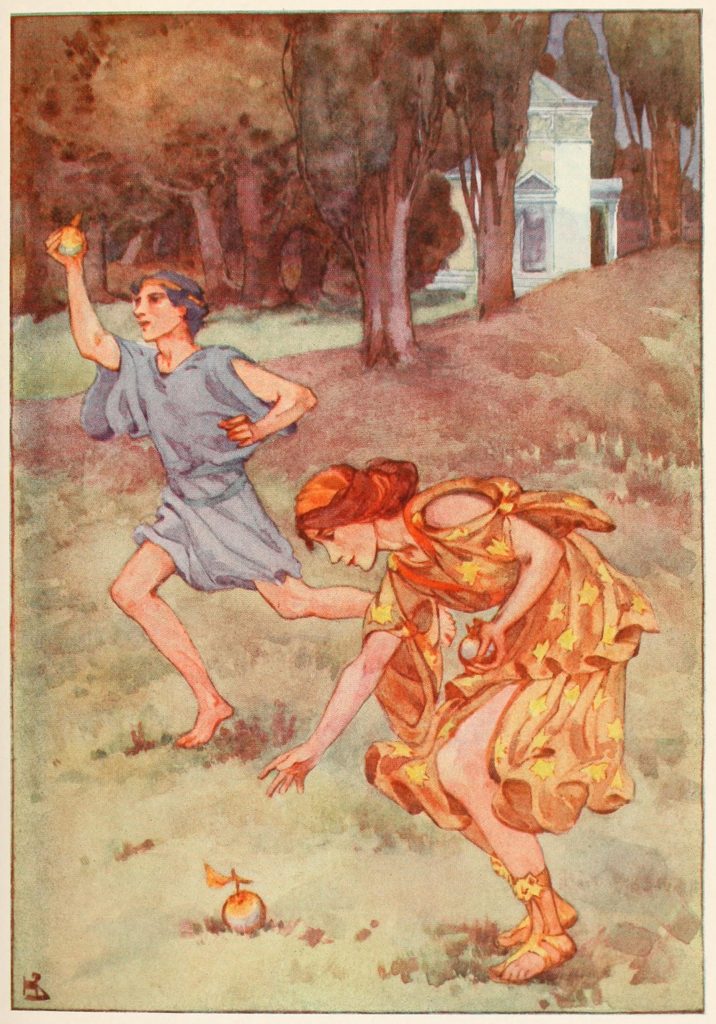

The first positive model was Atalanta, whose myth has two versions. Mixing them (as often happened in the Western artistic tradition), we can say that she was a hunter, devotee to goddess Artemis. Abandoned by her parents, she was saved and nursed by a she-bear. Grew up as a virgin hunter, she had a lot of adventures, such as the Calydonian boar hunt. Then her natural father (a king) decided to recognize her: of course, he wanted her to marry as soon as possible … Princess Atalanta set a condition: her groom had to outrun her in a footrace: otherwise, killing him would be her right. Her father agreed, and many suitors died before Hippomens met Atalanta, who quickly fell in love with her. Since Atalanta was very fast, he understood that he didn’t have to use strength, but his brain. As the race began, Atalanta passed the man, but he tosses a golden apple which Aphrodite gave him (of course, the goddess of love hated that heart-of-stone girl): being curious of the shiny item, Atalanta stopped to watch it. This happened twice more and by the end Hippomnenes won the race … and Atalanta’s heart.

Hippomenes and Atalanta (1701)

Source: https://bit.ly/3h4uNKj

Helen Stratton, ‘A book of myths’ (1915)

Source: https://bit.ly/3yKxiYm

Sculptures of Hippomenes and Atalanta in a pond with fountain at Quex House in Birchington, Kent, England

Source: https://bit.ly/3yFsmUJ

In late 1920s’ a small running Atalanta was used on the radiator of Studebaker Erskine cars …

Source: https://members.tripod.com/~erskine_registry/erskine.html

A contemporary version of the myth, sculpted in 1998/1999 by Swiss artist Hans Erni

Source: https://bit.ly/2WWScGE

Another interesting contemporary version of the myth, with a black Hippomenes and a white Atalanta

David Spears’ Race for Atalanta (2003)

Source: https://www.alleywayarts.com/warehouse/art_print_products/race-for-atalanta-38×16?product_gallery=64819&product_id=2947764

In 2007, even a comic book was released …

Source: https://lernerbooks.com/shop/show/10719

In 1930s’, the myth of Atalanta was well-known in Italy, even to those sports fan who couldn’t attend school: the football team based in Bergamo was named after her!

Atalanta Bergamo’s crest: as you can see from her flowing hair, it’s Atalanta running

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atalanta_B.C

In the 1960s’ crest, the whole body of running Atalanta was depicted

Source: https://1000logos.net/atalanta-logo/

In 2011, the team added this little running Atalanta on the official shorts (not on the chest), as a sort of tribute to the tradition

Source: https://www.passionemaglie.it/come-una-seconda-pelle-atalanta/

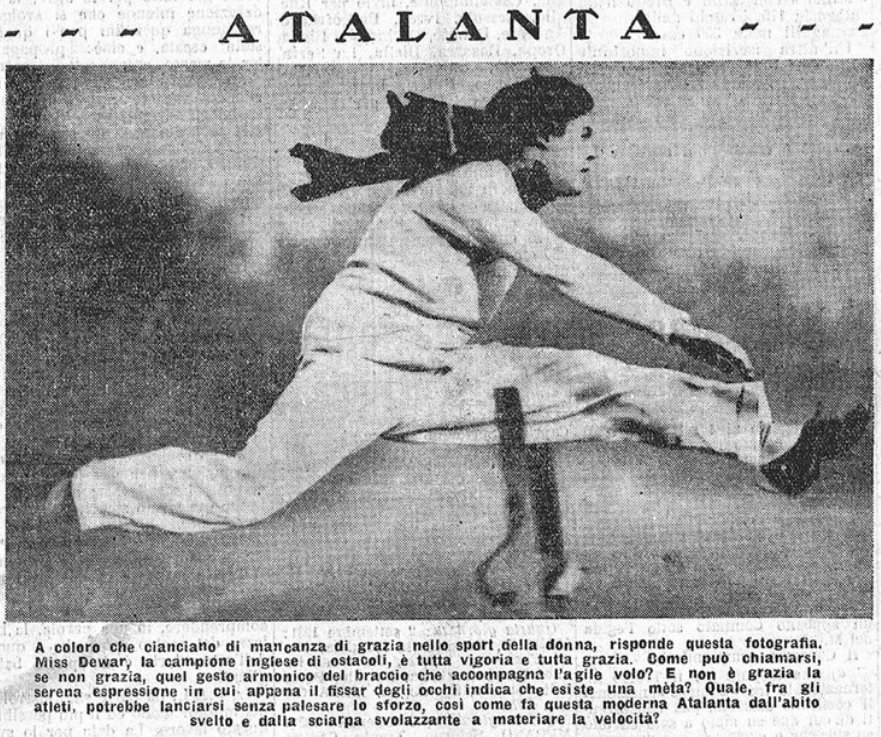

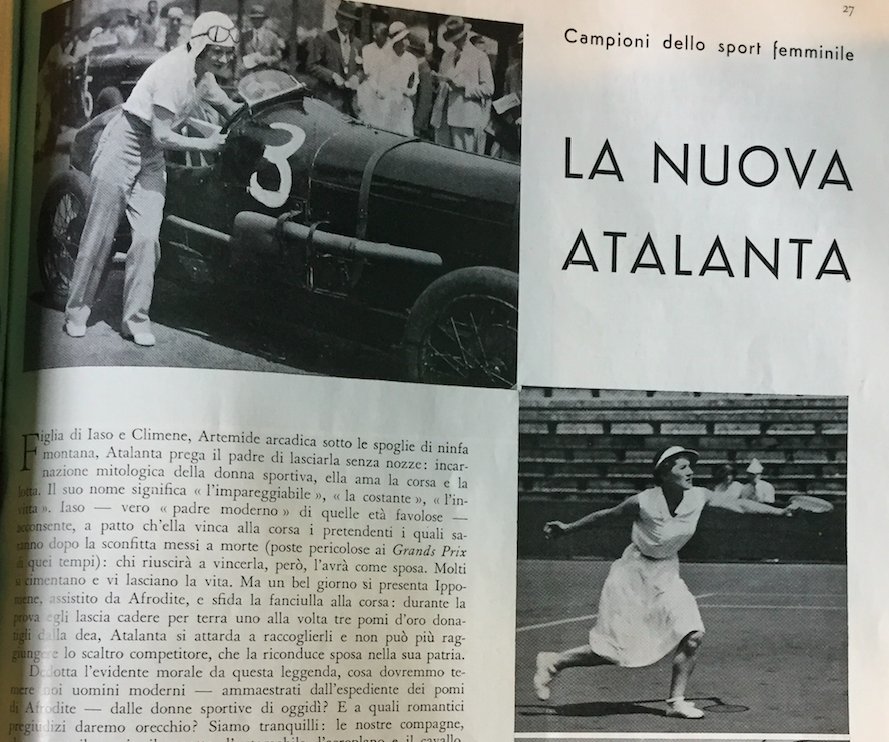

So female runners were called ‘Atalanta’ (or ‘modern Atalanta’) by the 1930s’ Italian press, which sometimes used this term more generally, for ‘sportswoman’. Because of the story told by the myth, she was a good example: because by the end she married, Atalanta was praised as quiet the rebel who loves sports, and finally accepts, willingly or otherwise, her fate as a bride. In this version, the race wasn’t interpreted as final proof, but rather as a sort of unusual courtship by Hippomenes: modern male lovers should practise sport, if they want to conquer the female heart!

The first part of the caption says

‘To those who talk about the fact that female athletes lack grace, we answer showing you miss Dewar, British hurdles champion, who is full of both strength and grace’

Source: Il Littoriale, 09/06/1931, p. 1

An article about sportswomen, titled ‘the new Atalanta’

Source: La Donna, July 1933, p. 27

A caption fromm the previous article

‘Let’s look to Atalanta during her favourite sport: footrace. Would you dare compete with her, not being the clever and fast Hippomenes?’

Source: La Donna, Luglio 1933, p. 29.

In this 1946 clipping from Elda Franco’s archive (see https:// http://bit.ly/3DtvKpg )

we can see how the use of ‘Atalanta’ for ‘sportswoman’ continued post 1945:

the female athletes of Italy and of Austria are called ‘the 30 Atalantas’

Source: Archivio privato Elda Franco, https://sorelleboccalini.wordpress.com/le-fonti_elda-franco_una-carriera-sportiva-attraverso-i-ritagli-di-giornale/

Yet Atalanta’s was still too scary: the woman was a hunter, and male blood could flow: a better example had to be found. Women’s sports supporters did it by reading Homer’s Odyssey, probably the most well-known Classical epic poem of that time in Italy.

Nausicaa was the daughter of Alcinous, king of Phaecia, a island where Odysseus was shipwrecked during his long journey returning home to his beloved wife Penelope. One day, the young princess and her maidens go to the seashore in order to wash their dresses. During a pause, they started to play ball, but at one point the ball goes into the sea, so they have to collect it, just in front of a bush behind which the naked Odysseus was hiding and watching them (he was woken by their screaming during the game). When they notice the presence of the naked stranger, all the women run away, except for the brave and empathic Nausicaa, who was touched by Odysseus request for pity. She decided to save him, bringing him to her father’s court, where he was given clothes and food.

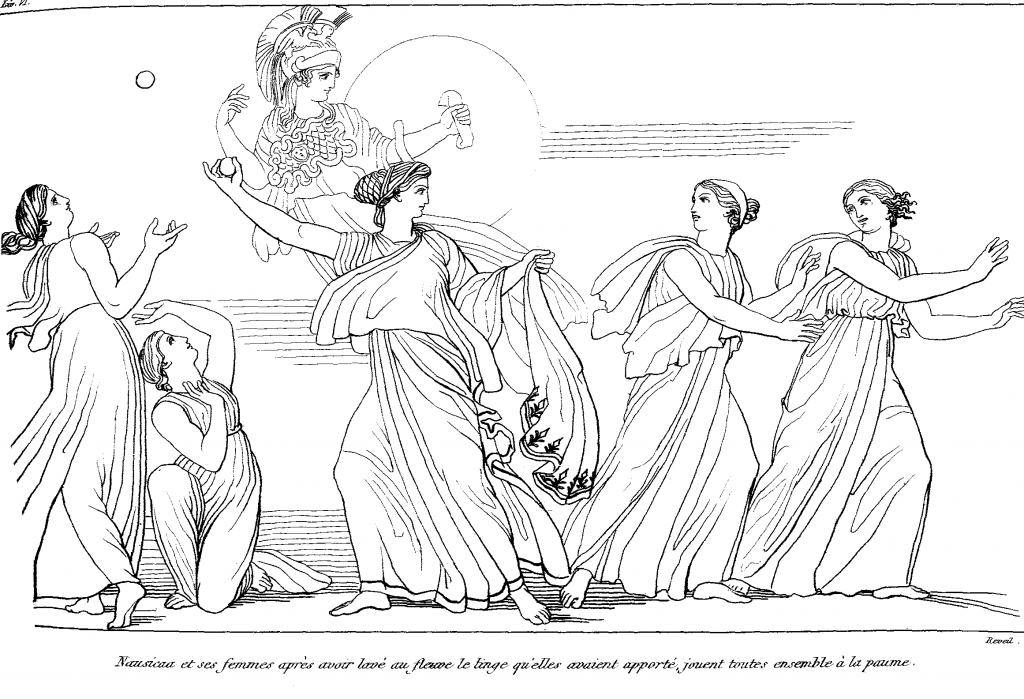

Nausicaa playing ball with her friends. From the illustrations of Odyssey by John Flaxman (1810)

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/John_Flaxman%27s_Odyssey

Jean Veber’s ‘Ulysses and Nausicaa’ (1888).

Source: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nausicaa_(nome)

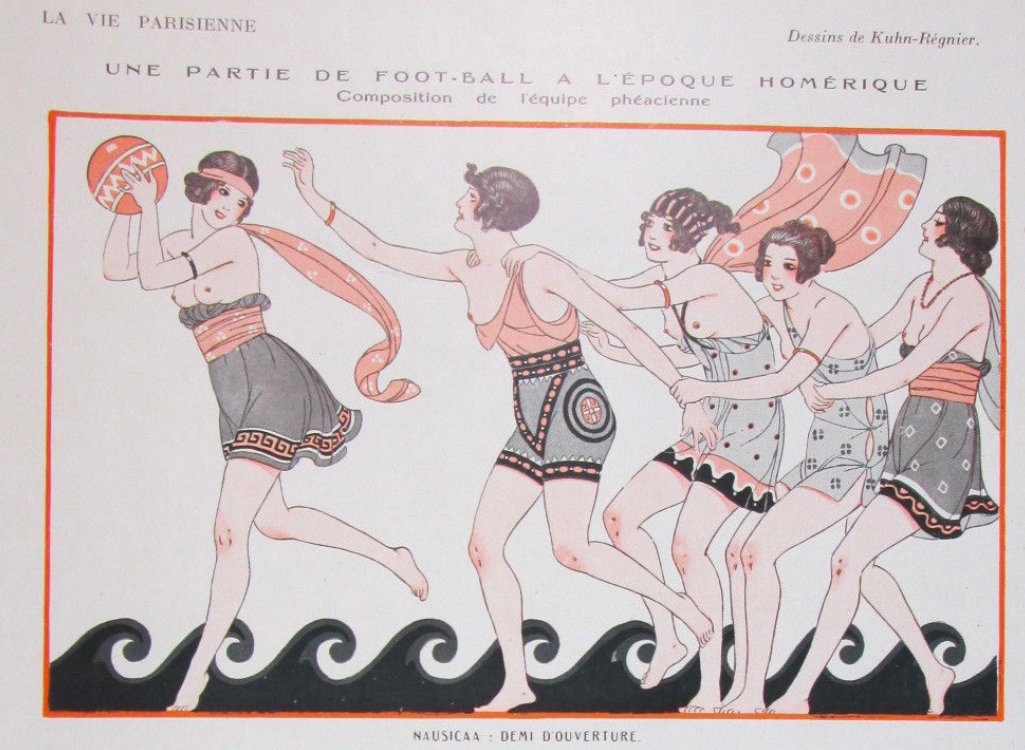

Nausicaa was indeed a model for women playing ball games, such as tennis – in France, even for football!

A quite lewd version of Nausicaa playing ball with her maidens, published by French magazine La Vie Parisien (1924): they’re depicted as footballers!

Source: https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1003737125194469376

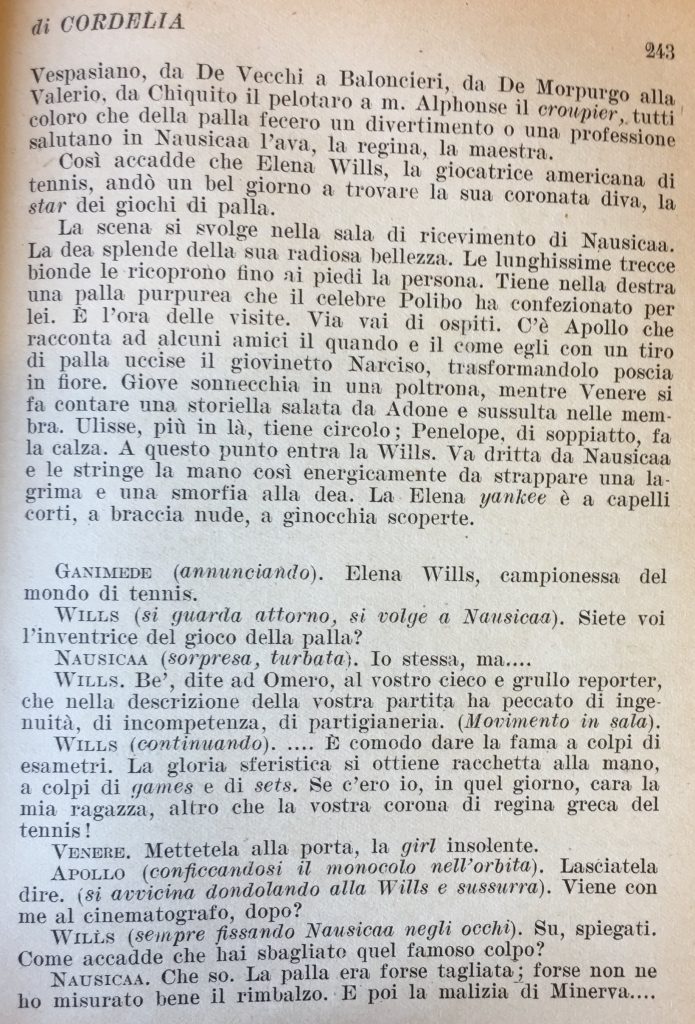

Italian journalist Bruno Roghi wrote an interesting tale, entitled La palla della principessa ‘Princess’ ball’, which was first published in 1930, and then became a novel (1931). The novel version is a quite bizarre work of fiction, set on Mars after total destruction (except for Nausicaa’s ball, which is an inanimate object) of mankind by the god Iuppiter, with ballplayers: yet Chapter I and II tell the same story as the orginal version. Roghi imagines that after her death Nausicaa was deified by the Olympic gods for the invention of ball games: so when every male/female ballplayer had to pay tribute to her, sitting on a throne. When US tennis players Ellen Wills (born in 1905 … who died in 1998) enters Nausicas’s hall for the tribute, she’s not at all intimidated by all the gods. She asks ‘Whos’ the inventor of the ball?’. When Nausicaa says ‘I …’, she started to complain that when Homer wrote about that first gall game he was naïve, incompetent, and one-sided: ‘Ball’s glory must be gained holding a racket, collecting games and sets. If I was there on that day, dear pretty girl, you would lose your Greek tennis royal crown’. Venus asks the guards to throw out the insolent American woman, Apollo asks her if she would like to hang out. Ellen asks Nausicaa: ‘Tell me, how could you have such a bad shot?’ ‘I don’t know … maybe it was a backspin, maybe I failed in calculating the ball’s bounce …’. Then Ellen asks Nausicaa leave the throne: she had the right to be then new ball’s goddess. This request caused a problem: the audience broke into two fractions, one for Nausicaa and the other for Ellen. Yet the princess says in her defence the words, that we can read as a sum of the Fascist image of sportswoman, who should be different from the those from abroad:

You’re right, girl, probably you won’t miss that ball: you would win the match and the ball wouldn’t go into the sea. But in that case, you and you’re maidens won’t wake up Odysseus with your crying … Homer wouldn’t finish his Odyssey, and Penelope, understanding that his husband was dead, would give in to her wedding suitors requests. Missing that ball, I gave to mankind a divine poem and to all women a perfect example of chastity and conjugal fidelity. You young star-and-striped Ellen, and you very-modern mates, are unbeatable champions: but most of the time you forgot to be women. Infallibility … such a dry and cynical virtue for Eve’s daughter!

A page from the first version of Bruno Roghi’s tale

Source: Almanacco di Cordelia 1930, pp. 241-244

The cover of the novel version, published by La Gazzetta dello Sport (1931)

Source: https://bit.ly/3h6GOyZ

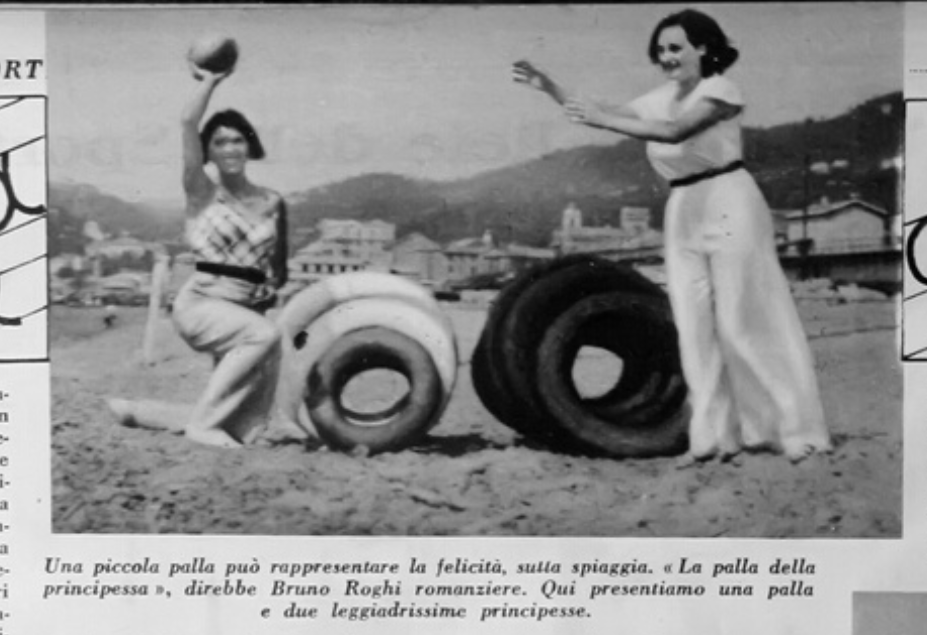

‘La palla della principessa’ became quite popular, as shown by this 1933 picture, where two La Domenica Sportiva readers tried to reenact it …

Source: La Domenica Sportiva, 13/08/1933, p. 6

Indeed the person who used Nausicaa as a symbol of a “sane” image of sportswoman the most was Alfredo Bertagnoni, who wrote an article in 1933 about women’s sports, saying that he and his colleagues weren’t looking for masculine Amazons, enemy of men, or for Penelope, who spent all her life doing housework, nor Athena, who dared to compete with men in the intellectual sphere (remember that Mussolini forbid Italian female teachers to teach in universities or high schools …). There was in fact a third way, and a third classical woman to imitate: Nausicaa, who played ball with her maidens during her youth, aware of and happy about her marriage fate. Sports and maternity found a perfect link in Alcinous’s daughter: because she had practised sports during her virginal youth, she would give birth to well-balanced children … which was the perfect answer for the Fascist policy in regard to women’s sports.

Article © of Marco Giani

For a gallery with some more images and sources:

https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1034897381978980352