Read the previous articles in the series: Part 1 Click HERE , Part 2 Click HERE and Part 3 Click HERE

Huge Problems in France and Belgium (1)

The 1932-33 season was the final one for French women under the guidance of the F.F.S.F. Although there were signs that women’s football had consolidated at a lower level, the federation decided to abandon women’s football before the season was finished, which means that there was no French champion and most likely no Paris champion. A decider for the Paris championship between Fémina and Dunlop, who were equal on points, was scheduled at St. Denis, but there are no signs in the sources that the match was played. The women football clubs took matters in their own hands during the summer and created a French women’s football federation F.F.F.F. (at first under the name of their Parisian championship: Ligue Féminine Football Association L.F.F.A.). In Belgium only five teams participated in the championship, which was again won by Atalante, who lost sensationally in the cup-final (which was postponed from spring 1932 to autumn 1932 as a consequence of the funeral of Sarah Meljado, player of Ajax and Fémina Antwerp) against Sporting Girls from Antwerp.

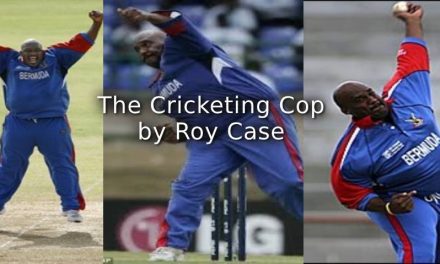

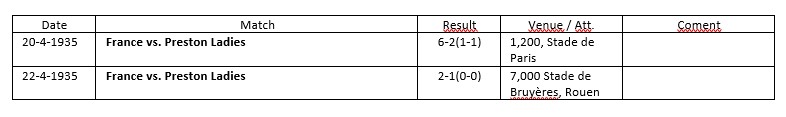

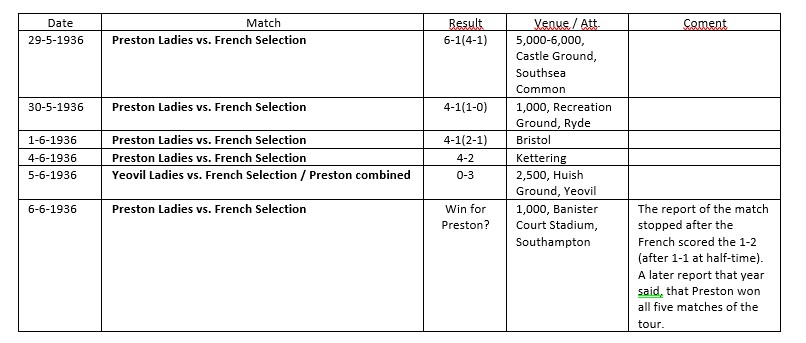

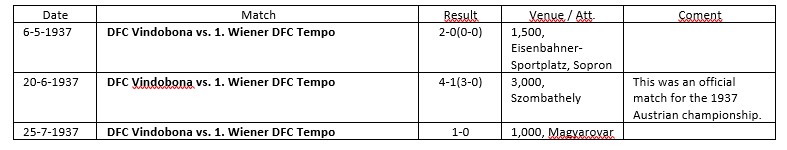

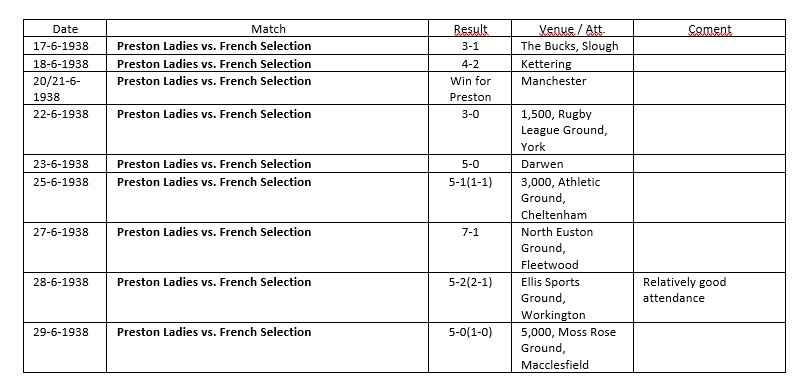

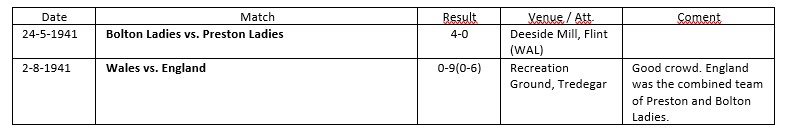

Table 4.1

Full internationals between France and Belgium 1931 and 1937

The annual international was played in Roubaix in front of a disappointing number of only 500 spectators. France was back on track winning 3-1. Unfortunately, the reporting of the matches had been getting worse and worse since 1930. This time no scorer was mentioned (the only case for a full international in that period). After a goalless first half France opened the score, Belgium equalised and finally France secured their win. France was the better team. For the first time it was Dunlop who had the most players in the French squad (5), followed by Fémina (3), and the clubs Olympique de Marseille, CRS 4-Chemins and Club des X with one each. Belgium had five Atalante players, three from Fémina Antwerpen, two from the Sporting Girls and one from En Avant in their ranks.

Scene from the full international France vs. Belgium in Roubaix

Source: Le Dimanche du Journal de Roubaix 1933-4-16 / Courtesy of Gallica BNF

Another Fémina tour (2)

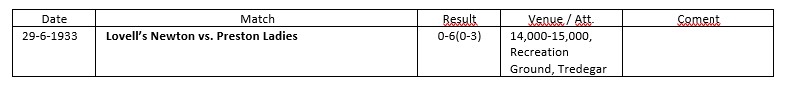

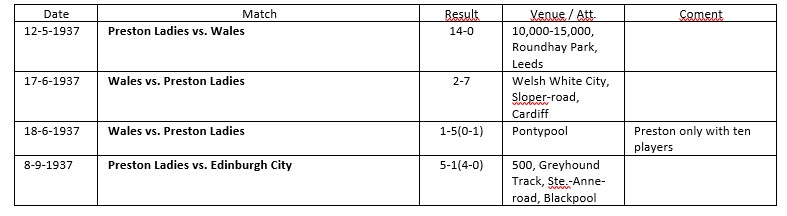

Fémina repeated their tour of 1932, playing six matches this time. Before that, Preston played another match against Lovell’s in Tredegar winning 6-0 before 14,000 to 15,000 spectators. England and Wales were the two countries with the most women’s football activities on the British Isles in 1933 and 1934.

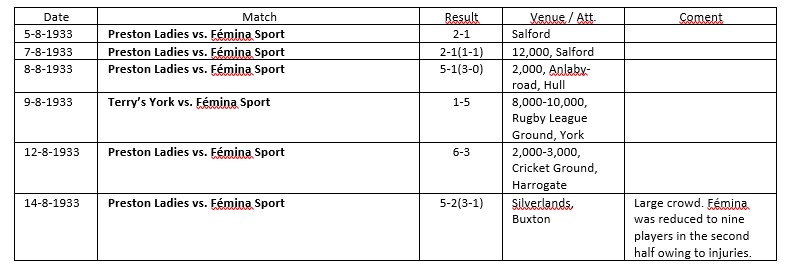

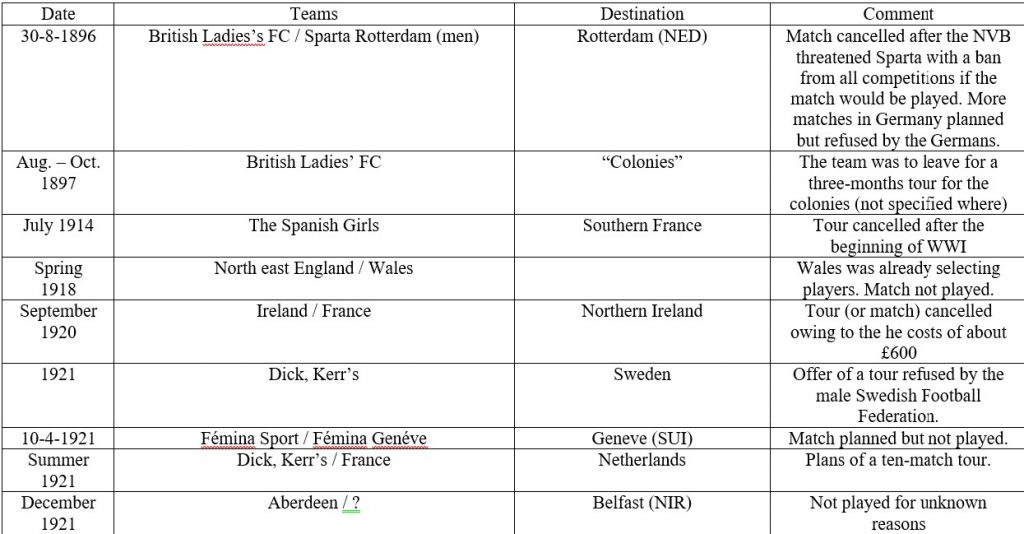

Table. 4.2

Fémina’s tour of 1933

Table 4.3

Lovell’s Newport vs. Preston 1933

With Manca-Guille returning from Olympique de Marseille after the club had abandoned their women’s football team, Fémina played with four players from the French national team, but over all this wasn’t the best France had to offer. Still, Preston was able to win the last three games at Hull, Harrogate and Buxton convincingly, while the two matches at Salford were close affairs as they both ended 2-1 in favour of Preston. The forwards Hutton, Thornborough and Chorley were the driving force of Preston these years. Fémina had the consolidation when they played Terry’s from York (The “chocolate girls”) in front of almost 10,000 spectators at York. This match showed that the gap between Preston and the rest of the teams from the British Isles was huge. Fémina had no problem winning 5-1.

Before the kick-off in Buxton

Fémina’s team is received by Deputy-Mayor A.J. Potter of Buxton

Source: Buxton Advertiser 1933-8-19 / Courtesy of Stuart Gibbs

Belgium’s best year (3)

During the year 1933 two more countries appeared on the women’s football map. In the Netherlands the women of the club Celcia from Den Haag played their first matches, and in Italy the Gruppo Calcatrici Milanesi played some matches in the Lombard region. The latter only continued until 1934 before they were practically banned by the Italian fascists.

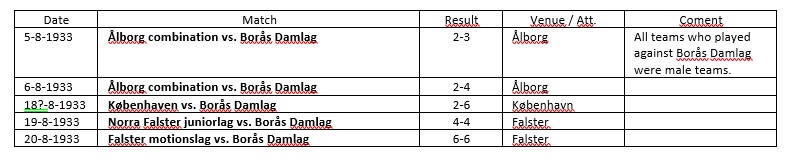

Sweden had had some tradition in women’s football since 1917, which is still being researched, but in 1933 one team joined the clubs that played international matches when Borås Damlag played six matches in Danmark against male teams in August. Most of the other matches by Swedish women teams were mainly against a local “old boys” teams.

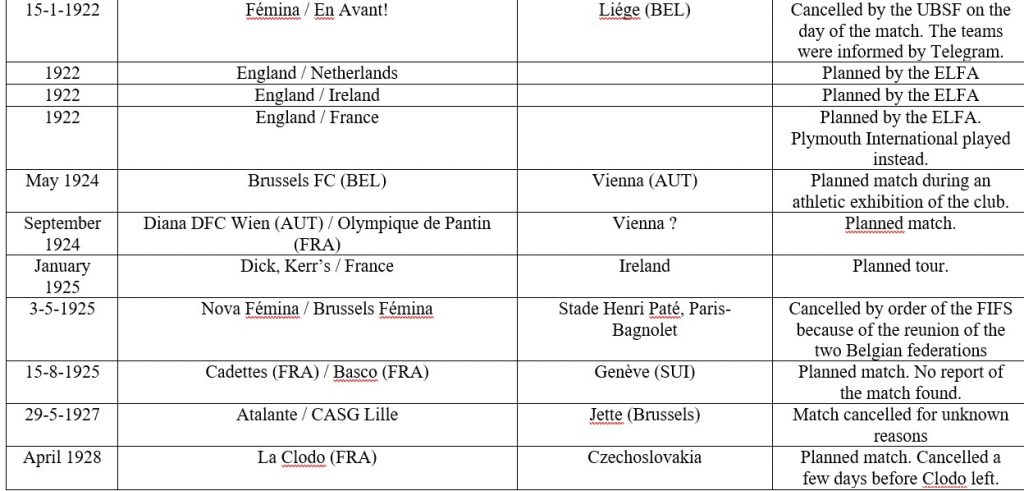

Table 4.4

Matches in Danmark by the Borås Damlag from Sweden

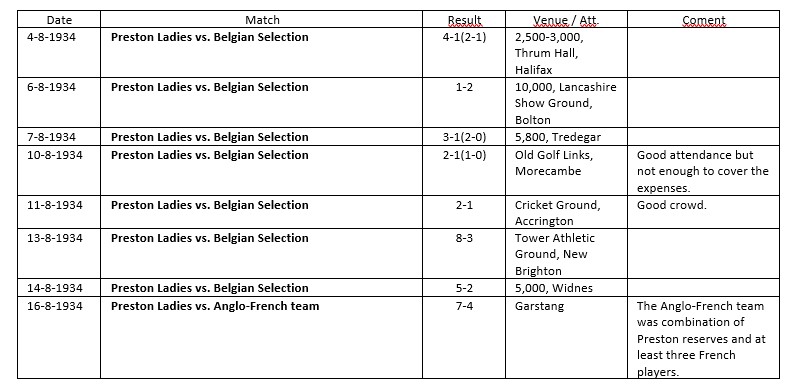

1933-34 was a historic season for Belgium. It was the year of the last championship (consisting only of four teams, three of which belonged to Atalante) and the cup. En Avant was the cup winner, Atalante won the championship. It was also the year of the first tour of a Belgian team to England (and Wales). A selection of players from Atalante and En Avant (resembling the national team that played France in April 1934) was the tour partner of Preston in six matches played in August 1934. One of these matches was played in Wales (Tredegar), the others in England (Halifax, Bolton, Accrington, New Brighton, Widnes) with Atalante only managing to win at Bolton (2-1) and losing the other five. Part of the tour were three players from Fémina with Carmen Pomiès as interpreter and Marie-Louise Droulet, who played in goal for Preston when A.C. Marsh was unable to play. The Belgian selection did pretty good in the first half of the tour but was unable to hold the standard in the final matches, culminating in a 3-8 loss at Morecambe. After the tour Preston played a match at Garstang against their “Rest of England” farm team augmented with the three French women who accompanied the Belgian team winning 7-4. The match at Bolton during the Lancashire show was the most memorable of the tour, as Preston and the press were constantly referring to the match as being their only defeat in years (which wasn’t exactly the truth), and that it was the stormy and rainy weather which was to blame for the surprising win of the Belgian team. Rachel Donvil was their best scorer during the tour. Unfortunately, the tour didn’t get the medial coverage it would have deserved. Most of the reports didn’t provide relevant details like line-ups etc.

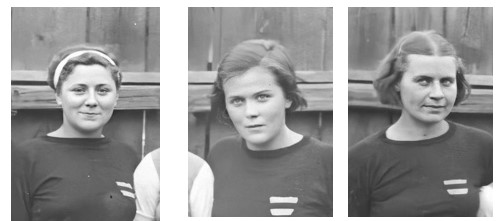

Three of Belgium’s best players in the 1930s

(left to right): Top-scorer Rachel Donvil, Denise Glise and Henriette de Meyer

All three of the played for Atalante de Jette and were part of Belgians 1934 triumph over France

Source: Archive: Helge Faller

The win against Preston in August was something but Belgium had their most important win on 28th April at Paris-St. Ouen when they beat France for the second (and last) time in the inter-war period. Though France was the better team, Belgium scored two times in the second half through Rachel Donvil after counter-attacks. For the newly formed F.F.F.F. this was a setback. France played with seven players from Fémina (interestingly enough without Pomiès) while the others came from Dunlop (3) and CRS-4 Chemins (1).

Three French internationals during the 1930s

(left to right): Elsie Delpuech, Boutniaud and Jouvé

They also played for Fémina in the first half of the 1930s

Source: Archive Helge Faller

Table 4.5

The tour of the Belgian selection through England and Wales 1934 and the Garstang match.

Since 1934 the centre of women’s football on mainland Europe was shifting eastwards. An exception were the Netherlands, where women’s football was flourishing with teams being formed in Den Haag, Rotterdam, Amsterdam, Delft and Leiden, including the formation of regional and one national women’s football federation (Nederlandsche Damesvoetbalbond). Although there were many matches between the clubs, there was neither an official national championship nor an international match. The K.N.V.B. (the male football association) banned women’s football in 1936, and it almost completely disappeared until the mid-fifties. But in Austria and Romania women began to play football and, in a way, took the torch from France and Belgium.

French dominance despite the decline (4)

In France only six teams participated in the Paris championship. The days of the Fémina dominance were definitely over. One reason that year was that they lost four matches by walk over against the two Dunlop teams as they protested against Violette Morris, who was to play for Dunlop. Morris finally decided not to play but Fémina upheld their protest. The championship was won by Dunlop A(?) in a championship decider against En Avant!.

But the French footballers were in great form in 1935. In the match against Belgium on 23rd March at Saint-Ouen, France played without Fémina players for the first time since 1924. The club had lost several players during the season to other Paris clubs. Six players were from Dunlop, three from Stade Châtillion and two from Club des X. Belgium with a Atalante / En Avant combination including Van Truyen, who was a member of William Elie. Belgium was good in the first half but wasn’t able to get past the defenders Concord (Stade Châtillion) and Bonin (Club des X) and goalkeeper Jouve (Stade Châtillion). In the second half, France put more pressure on Van Truyen and newcomer Bardin (Club des X), and directly converted a pass by Despau (Dunlop) for the winner.

In April, Preston came to France for the first time since 1920. After their convincing victories during the Fémina tours, it was expected that Preston would also beat the national team (again without players from Fémina). Lily Parr was a prominent absence in Preston’s squad, but she wasn’t in the form of the 1920s, and on the other hand France was playing without Pomiès. The first match was played at Stade de Paris in front of only 1,200 spectators. In the first half Preston had the wind and the sun behind them and were a bit better than France, whose players were a bit nervous. But as the defence stood firm, the French players gained confidence and attacked the Preston goal. Bardin scored first when Cunliffe left her goal to defend but with bad. Preston then equalized. However, that goal was disallowed for offside. But the English women remained patient, and Buxton finally scored the equalizer without any reaction by goalkeeper Jouve, who thought it was offside. In the second half, France was by far the better team and scored twice through Jeannot-Braqcuemond, who played one of her best matches for France. Bardin was responsible for the 4-1. That goal was a bit of a wakeup call for Preston. Thornborough reduced the French lead with a good shot but it was France’s day. Two more goals by Jeannot-Bracquemond secured an unbelievable 6-2 win for the French national team. For Preston this was their heaviest defeat in their 18 year team history. Apart from the two scorers and the goalkeeper, Villedieu and Ferrat (both Dunlop) were the best players of France. Chorley, Lynch and Buxton were named best players for Preston. Cunliffe in her first important match for Preston was the weakest player of the team.

The French goalkeeper clears before the Preston forwards (dark shirt)

but it was all France in the first match between the French national team and Preston since 1921

Source: Miroir des Sports 1935-4-23 / Archive Helge Faller

In Rouen, 7,000 people watched the second match between France and Preston. Although Preston had a technical advantage, and with Lynch the best player on the field, they were not able to get past the firm French defence. At half-time the score-sheet was still blank. In the second half, France was the better team, and after 43 minutes Despau scored the first goal for France. The spectators were now enthusiastically cheering for the French team but it was Preston who scored next seven minutes later. Lynch beat Jouve with a 25m shot. Shortly after the goal, Lynch tried a long-range shot again but this time Jouve cleared. Not shocked the French women were attacking again, and finally it was Despau again, seven minutes before the end, who scored the winner. Preston had lost both matches in France against a team playing better than the former best team of the world. In an interview after the match in Rouen, Jeannot-Bracquemond enthusiastically stated that these two matches were a huge benefit for women’s football in France.

Table 4.6

France vs. Preston in 1935

In July and August, Fémina came to England for the fourth time with two prominent guest players (Brataux of Dunlop and Gallien of Châtillon – both had played for the French national team). As several good players had left the pioneer club, they were not the team that had won seven French championships in a row. But Preston was also not in their best form. Parr only played occasional matches for her team during the mid- and late 30s, and the two matches in France had a sobering effect for the Preston Ladies. Preston played six matches against Fémina, and most of the results were close, Fémina even managed to win at Leyland 3-2, which was only their second win against Preston. The match in West Ham received some coverage abroad (for instance in Austria), as it was played in aid of the British Empire Cancer Fund. Half of Preston’s goals were scored by Edith Hutton, the new star forward of the Lancashire team. Fémina’s only prominent players were Pomiès and Maugars-Arsac.

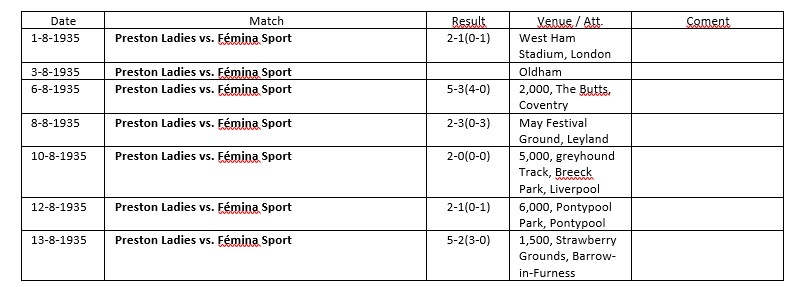

Table 4.7

Fémina’s tour of 1935

In September at Caudry, a Belgian selection upset the new French super-team C.A. XIV de Paris (including Jeannot-Bracquemond and several other French internationals), beating the upcoming Paris champion 3-0.

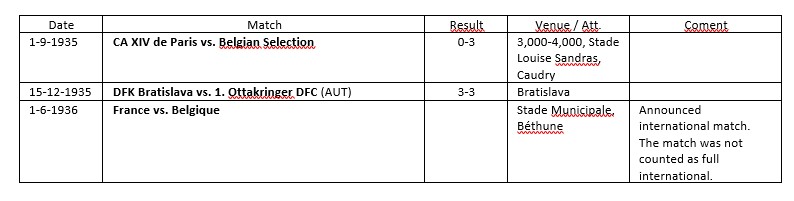

Table 4.8

Internationals by club teams and selections in the 1935-1936 season in Europe

Austria – the new pacemaker of women’s football (5)

In October, women’s football had a great start in Austria when the teams D.F.C. Austria and Ö.D.F.C. (Österreichischer Damenfußball Club = Austrian Ladies’ Football Club) Wien played the first match of the new era on 13th October. This was not the first women’s football match in Austria (which dates back to 1923), and one week earlier the two teams of the 1. Wiener D.F.C. (later Tempo Wien) had played against two male youth teams, but it was widely recognized at that time as the first proper women’s football match in Austria. Several matches followed, and in December 1935 the small team Ottakringer D.F.C. from Vienna played D.F.C. Bratislava from Czechoslovakia in Bratislava (3-3) in the first real international match by teams from these two countries. (There was one occasion in 1926 as part of an international swimming match in Vienna, where the swimming-clubs of Danubia-Hakoah Wien and Germania Berlin played a match which lasted ten minutes with a big beach ball. Berlin won the match 1-0). The women from Bratislava had a brief “boom” only lasting a couple of weeks during October and December 1935, resulting in the foundation of three teams. But women’s football continued in Czechoslovakia. Brno in Moravia was the new centre of women’s football. Romania was another country in the eastern parts of Europe where women football had a good start resulting in an unofficial championship in 1935, which was won by Arad.

1935 and 1936 were crucial years for women’s football in Europe. England and Scotland had their best years since the early 1920s, Wales and Northern Ireland, on the other hand, were on the decline with only a handful of matches been played. In France, the F.F.F.F. and their clubs tried hard to avoid the end and still managed to play the Parisian championship. In 1936, the new “super-club” CA XIV was champion with a 93-0 goal-average after 14 matches. Austria was the heart of women’s football with a national championship, a women’s football federation (Ö.D.U.) and an abundance of matches notwithstanding the ban by the Ö.F.B., the male football federation of Austria, which left only three small football fields for the women in Vienna. In addition, the Ö.F.B. ended all efforts to form teams outside Vienna and caused several of the new clubs in Vienna give up. (The Netherlands have already been mentioned.?)

Edith Klinger founded the club 1. Wiener DFC (late: DFC Tempo) in late 1934 and initiated the Austrian women’s football boom of 1935-1938.

She was a charismatic sports woman who also became the first female referee with an official license by the male Austrian football federation ÖFB

Source: Archive Helge Faller

A French selection toured the United Kingdom twice. In late spring, they played in the South of England, in the summer, they visited Lancashire and also Belfast for the last time before the war. The selection was not the national team but a squad put together by Pomiès with several good players from the women not selected for the national team, and one or two internationals. The tours were financial disasters for Preston. The mediocre French team was no threat for Preston, who were in better shape than in the previous year and won all five matches during the southern tour. A combined French / Preston team also beat Yeovil, one of the good new teams of the 1930s, 3-0. In the summer tour at least four matches were played between Preston and the French selection (there is the possibility of one or two further matches).Preston, who fielded two newcomers from Southampton (the Pragnall sisters) and their upcoming star Daphne Coupe, dominated the first three matches but were held to a 1-1 draw in the final game in Nelson. This French B selection (in which Pomiès / Fémina, Hourdequin / Club des X and Rita Lefébvre / S.C. Châtillon were some prominent players) was far too good for Northern Ireland. In front of only 2,000 visitors France easily won 4-1. Molly Seaton wasn’t able to live up to her form of four years ago, and the whole team lacked experience, as there were only occasional matches in Northern Ireland.

Two iconic figures of Irish and French women’s football at the arrival of the French selection in Belfast

Carmen Pomiès, shaking hands with the Mayor of Belfast and on the far-right Winnie McKenna, who organized the 1936 match together with Molly Seaton

Source: Northern Whig 1936-8-8 / British Newspaper Archive

Table 4.9

The spring-tour of the French selection

Table 4.10

The summer-tour of the French selection

The clubs D.F.C. Austria from Vienna and 1. Čs.D.F.K. Brno played their international debut in Brno. Austria had won the spring championship and was the superior team in Austria during the season, which was played from May to December. Brno had not had played a big match yet, so Austria was favourite. In front of 2,300 spectators the upcoming Austrian champion lived up to their reputation and won 7-1.

The 1. ČsDFK Brno played against teams from Austria and Yuguslavija

Source: Illustrierte Kronen-Zeitung 1936-9-25 / Österreichische Nationalbibliothek

Table 4.11

International matches between Brno and Austrian teams 1936 and 1937

The full international of 1936 between France and Belgium was played in Paris for the last time before the war. France was the dominant team during most parts of the match. Belgium only had some good moments when they started counter-attacks. The only goal of the first half was scored when Pomiès converted a penalty, after Maria Simon (Atalante) had committed a handball in the penalty area. In the second half, France had to switch positions as Jeannot-Bracquemond had torn a muscle. Nonetheless France was still superior. Pomiès scored her second goal after a pass by Despau, but Belgium was able to reply with a great goal by Rachel Donvil. During the final stages of the match France was pressing for a goal, and Pomiès scored her third goal. Again, the goalkeeper of Belgium, Van Truyen, was the best player of her team (the only player who didn’t play for either Atalante or En Avant). France played with nine players from CA XIV, the by far best team that season. The only exceptions were Pomiès (Fémina) and Leblond (AS Préfecture de la Seine). For Pomiès this was the farewell match for the French national team, ending her career in style with three goals. 1936 was her best international year goal-wise as she also scored ten goals during the two tours by the French Selection in the UK.

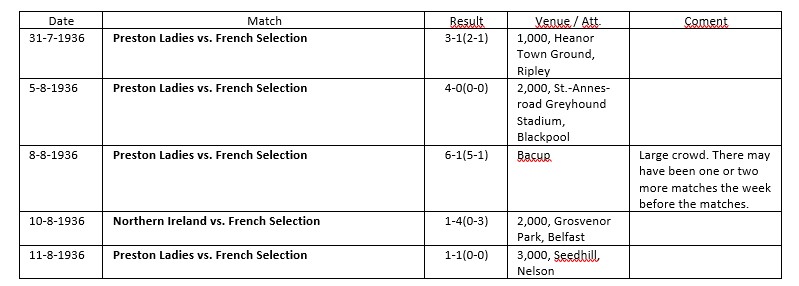

The “international year” 1937 (6)

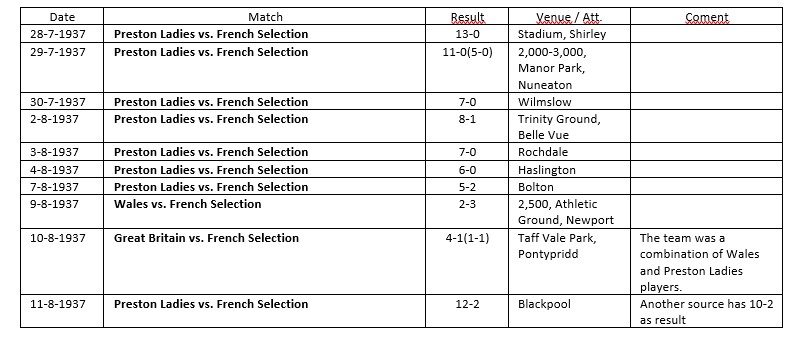

In 1937, a record of 27 matches was played in Europe (at least). Preston Ladies played Wales three times and were far superior winning all three matches with a total goal-average of 26-3. On 8th September 1937, Preston played Edinburgh City Ladies in front of only 500 spectators in Blackpool winning 5-1. This match was announced as “Championship of Great Britain” and later even called “World Championship”. Both titles are of course pure fiction as no international body recognized this match as an official match. Preston never played a female team from Central or Eastern Europe or any other country in the world apart from France and Belgium. Edinburgh City, on the other hand, had never played any international match prior to this “World-Championship”, so there was no reason, why they were playing a final for an international title. And the only time during the 1930s, when Preston played the real French national team, they lost both matches.

Table 4.12

Preston’s international matches in Great Britain in 1937

During July and August, another French selection toured England and Wales. The French team was by far the weakest team that was visiting Great Britain with many third-rate players. The devastating results (with even some double-figures losses) were therefore no surprise. After some players of France had to leave early during the tour, they even were not able to field eleven players in their last match. Two interesting games during the tour were played in Wales though, when the French team beat Wales 3-2 and lost 2-4 against a combination of Welsh and Preston players (under the name Great Britain).

Table 4.13

The tour of the French selection through England and Wales in 1937

DFC Vindobona before their first international match in Brno, including three guest players from DFC Austria

Back row (left to right: Scher, Wetzer, Zaunrith, Hallawitsch, Lovato

Middle row (left to right): Krobath, Peternell, Henych

Front row (left to right): Binder, Pliska, Aschauer

Austria was playing their second championship and their first cup. D.F.C. Austria won both with Ö.D.F.C. Wien as their fiercest rivals. The teams from Austria were very active in playing international matches or exhibition matches in Hungary. These exhibition matches, in a country where all tries to establish women’s football failed during the second half of the 1930s, were something special. Three matches were played in 1937, all before a very good crowd. One of these matches (D.F.C. Vindobona vs. 1. D.F.C. Tempo) was a match of the Austrian championship played in Szombathely. As far as we know, this was the first official competitive domestic match in women’s football that was played in a foreign country.

Three of Vindobona’s best players

Gusti Lovato, Austria’s top-goalie Anny Pliska and top-scorer Zaunrith

Source: Archive Helge Faller

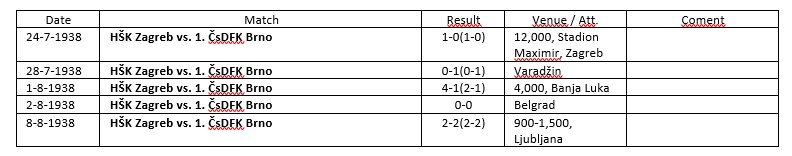

Table 4.14

Exhibition matches in Hungary in 1937

The Czech team 1. Čs.D.F.K. Brno played eight times against Viennese teams and improved during the year but never was able to win against a team from Austria. In March, D.F.C. Vindobona (augmented with players from D.F.C. Ausria) played two matches in Brno winning both convincingly 5-2 and 4-1. In May, Brno played in Vienna for the first time in a small tournament in which D.F.C. Austria and D.F.C. Vindobona played against Brno and D.F.C. Rapid, while Brno only played Austria and Vindobona. Austria won this tournament on goal-average as both teams beat Brno and Rapid (Austria: 6-2 and 9-0, Vindobona: 5-2 and 6-1). In autumn, Ö.D.F.C. Wien and Brno played each other four times in Vienna and Brno. Brno was able to draw two matches against the Austrian vice-champion.

Three of Brno’s finest players

(left to right): Ğlezingerová, Faldikova and top-scorer Stejskalova

Source: Archive Alexander Juraske

Some of most important players of the Austrian teams during that period were Josefine Lauterbach (D.F.C. Austria), top scorer in the Austrian championship, who had started football in 1924 learning from Austrian legend Mathias Sindelar and participated in the 1928 Olympics. She also played handball. Then there were also the young Leopoldine Kantner (D.F.C. Austria), Emilie Redl (Ö.D.F.C. Wien), the great goalkeeper Anny Pliska (D.F.C. Vindobona) and Leopoldine Binder (D.F.C. Austria). The woman who had started it all was Edith Klinger. She founded the club 1. D.F.C. Tempo (under the name D.F.C. Kolossal) in 1934 where she also played and was the leading figure in the early development of Austrian women’s football. She also became official referee of the Ö.F.B., the male federation, thanks to a lack of clarity in the rules which didn’t prevent women from participating in the referee courses. The Ö.F.B. reacted soon after that and excluded women from referee courses in the future. Another important person in Austrian women’s football was Alice Maibaum, player for Tempo and secretary of her club and the Ö.D.U. (the women’s football federation), who was only 18 years old when she obtained her post in the federation and emigrated from Austria to the United States after the German occupation, as she and her family were Jewish. She stayed in Brooklyn / New York during the war and married.

-

Leopoldine Binder played over 100 matches in her three-and-a-half-year career for DFC Austria

She was also capped several times for several selection matches

Source: Archive Helge Faller

-

Emilie Redl, on of Austria’s best forwards during the late 1930s played for the Österreicher DFC Wien

and is record holder for the most goals by an Austrian team in interwar international matches

Source: Archive Helge Faller

-

Josefine Lauterbach started playing football in 1924 and participated in the 1928 Olympics

After playing handball for several years, she joined DFC Austria and became top-scorer in the Austrian championship

Source: Archive Alexander Juraske

-

Leopoldine Kantner, one of the youngest players for DFC Austria

but also one of the best forwards of her time who was together with Lauterbach responsible for most auf Austria’s goals

Source: Archive Alexander Juraske

Brno had not much opposition in their home-country (there was only one more club), so they needed these international matches to play. The most important woman for the Czech club was Libuše Drahovzalová, the goalkeeper who was organising the club (and became a prominent figure in the rebirth of women’s football in Czechoslovakia after the war). Other good players were Stejskalova (their top-scorer) and Faldikova.

Scene from the match at Blackpool between Preston and the French selection

Source: Lancashire Evening Post 1937-8-12 / British Newspaper Archive

The year 1937 was in some ways a farewell season for France. The Paris championship proved to be the last before the war with C.A. XIV defending their title. The two internationals played in may were the last full internationals for France and Belgium before the 1970s and the last before the war. On May 9th 1937, the first of these two internationals was played in Le Havre. 2,000 people came to see the match, and they saw a very good performance of the French women with a hattrick by Jeannot-Bracquemond. The rain in the first half didn’t stop her from scoring twice, adding another in the second half. Again, the French team consisted mainly of players from C.A. XIV, again champion of Paris.

Three weeks later, both teams visited Cherbourg for the final international before the war. 2,500 people came on a very hot day and saw a Belgian team that played much better than in Le Havre. No goals were scored during the first half but in the second half Belgium was on the attack, and in the 39th minute Simon opened the score with a free-kick. France reacted and after a handball received a penalty which Rita Lefébvre converted. France was now looking for the winning goal. Jeannot-Bracquemond missed what seemed like a certain goal but two minutes before time she scored after a pass by Despau, and with the same result as in the first match 1924 the history of inter-war full internationals terminated.

France leaving the field after they’ve won the last full international before WW II in Cherbourg against Belgium

Source: Cherbourg Éclair 1937-6-1 / Courtesy of Gallica BNF

Central and Eastern Europe (7)

In 1938 and 1939, the political circumstances ended several of the activities by women footballers across Europe. In 1938, Austria was occupied (the so called “Anschluss”) and became part of the Third Reich (Nazi Germany). For the women footballers in Austria, this was a turning point. Although they tried to show their goodwill to the new leadership by changing the name of the federation to D.Ö.D.U. (German-Austrian Ladies’ Football Union), the German sports organisation D.R.L. forbade the women to train and play in June 1938, and by August 1938 the women’s federation was eliminated. But for almost half a year the Deutsches Reich had a women’s football association. One year later, the German occupation of Bohemia ended women’s football in Brno, although a new team from Prague was able to play until 1941.

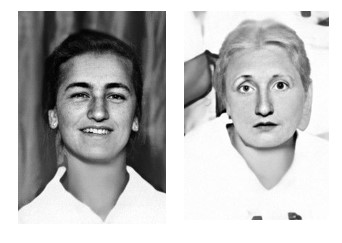

Yugoslavia was another country where women football started in 1937, thanks to the influence of Austria. The first team was founded in Borovo but the most important team came from Zagreb: HŠK Zagreb. In July 1938, Brno came on a tour to Yugoslavia playing five matches. Though the Czech team was more experienced, Zagreb won two matches, Brno only one (their only international victory) drawing the other two. The first match of the tour was played at Maximir Stadion in Zagreb in front of 12,000 spectators. Six weeks earlier, the national women’s football association (J.Ž.L.N.S.) had been founded, and there were plans for a championship starting in 1939. After the association had at first been recognized by the governmental sports authority M.F.V., this body finally withdrew their permission in early 1939, which caused most of the clubs to give up their football activities. The reason for the change of mind by the M.F.V. were concerns by men that women’s football could harm the female body, especially their childbearing ability. The best player was probably Marica Cimpermann, a celebrated athlete.

Table 4.15

Brno’s tour through Yugoslavija in 1938

On the left: Marica Zimmermann, Yugoslavija’s best female footballer and player for HŠK Zagreb in their international matches against Brno

On the right Marijana Oman, Zagreb’s right full back

Source: Archive: Helge Faller

Left to right: Birğelova, Petrželková, Kovarikova played in all international matches for Brno between 1936 and 1938

Source: Archive Alexander Juraske

France, although domestic football disappeared almost completely in 1938, had one final tour with their B-team that played in England in 1936. Nine more games were played in June with Preston winning all of these easily. The tour brought the two teams to their physical limits. Both teams had some trouble with injuries. Pomiès hurt her thigh, and when she returned for the last two matches, she was visibly limping. Preston had to play their last match with ten players. Lily Parr played several matches during the tour and proved that she definitely hadn’t lost her scoring-ability. These matches ended serious international women’s football in France for quite a while. The matches played in the late 40s and early 50s against Preston were by a team comprising mainly athletes and very few footballers who had played before the war.

Table 4.16

Farewell-tour of the French selection in 1938

Farewell tours (8)

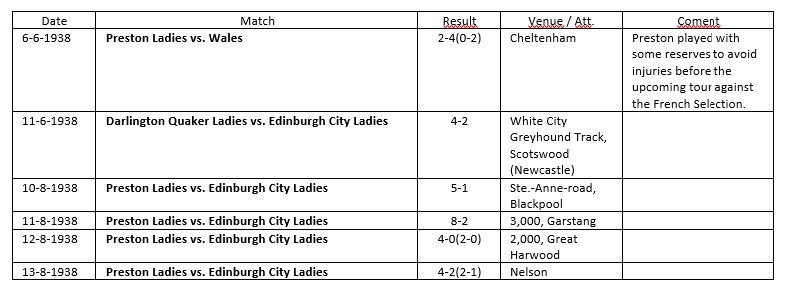

The were some inner-British internationals. Preston played Wales with several reserves as they didn’t want to risk any injuries before the matches against France. Still, it was a surprise that Wales was able to win 4-2 at Cheltenham. The Edinburgh City Ladies played the Darlington Quaker Ladies and lost 2-4 at Middlesbrough. A tour in August with the Preston Ladies resulted in four straight losses for the “Scottish champions”, as they were called. But women’s football was played on a frequent basis in both England and Scotland while in all of Ireland women’s football had disappeared, and in Wales the W.F.A. had finally banned women’s football.

Table 4.17

International matches in Great Britain in 1938

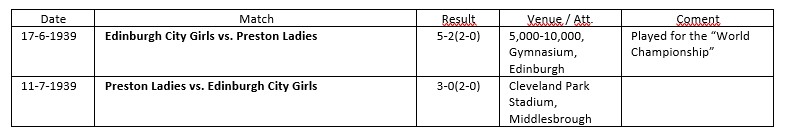

In 1939, international women’s football was only played in England and Scotland. Preston and Edinburgh were playing for the “World Championship”, without the rest of the world participating. But these two matches were perhaps the best matches that year, and Edinburgh had improved remarkably thanks to Nancy Thompson and returning Linda Clements (who played for Darlington), two of the best Scottish players of the inter-war period. The first match was won by Edinburgh 5-2, in the return match at Middlesbrough, Preston turned the tables by winning 3-0. Like in the 1920s, when there were Preston, Stoke and Rutherglen claiming to be “world champion”, there were now Preston and Edinburgh claiming this inofficial title. Nancy Thompson joined Preston after these matches.

Table 4.18

Preston vs. Edinburgh in 1939.

One of the most interesting matches in Great Britain were the two 1939 encounters between the Edinburgh City Girls and the Preston Ladies

After beating Preston 5-2 in Edinburgh for the so-called “World-Championship”, Scotland’s best team of the 1930s lost 0-3 in Middlesbrough

The scene is from the latter match

Source: North Eastern Gazette 1939-7-12 / Courtesy of Stuart Gibbs

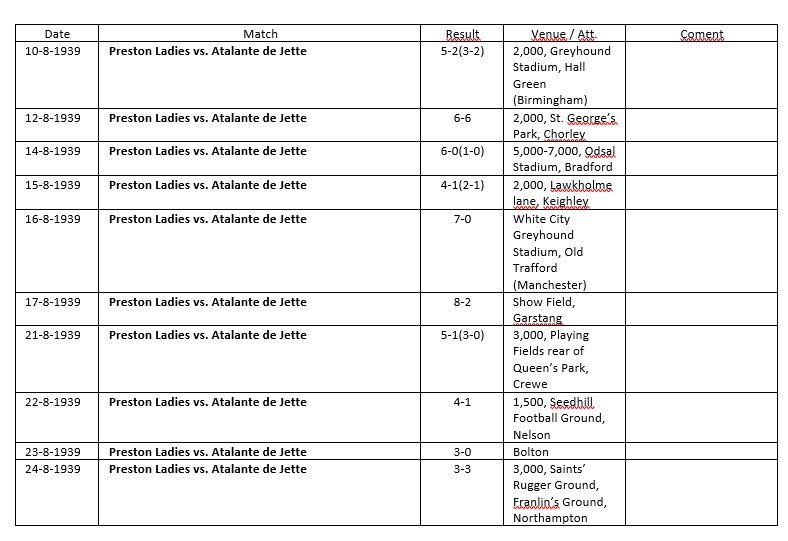

In August, Atalante de Jette played several matches against Preston in England. This happened to be the farewell tour of Atalante. Led by Françoise Desmedt, who had been playing football since 1923, Atalante lost most of the matches by a large margin. The team was overaged and hadn’t had much practise and match experience the last couple of years. The Belgian team was able to hold a draw against the much better team from Preston, though the first one at Chorley sounds a bit strange (6-6). The newspaper reports confirm this result, but one source gave Preston a 6-0 win. The second draw came in the last match at Northampton, when Preston and Atalante played 3-3.

Table 4.19

Atalante’s farewell-tour in 1939

Atalante toured England to play Preston Ladies one final time in 1939, just before the outbreak of WW II

The scene is from the match in Birmingham

Source: Birmingham Mail 1939-8-11 / British Newspaper Archive

- Left to right: The international players Josephine Marien and Maria “Mimi” Simon were part of Atalanta’s final tour in 1939

- Source: Archive Helge Faller

International football continued until 1941. On 24th May 1941, Preston and their new rivals Bolton played an exhibition match at Flint which Bolton won 4-0. On 2nd August 1941, Tredegar was the venue for the last international match we currently know of before 1946. Wales, fielding some players who had won against Preston in 1938, were no match for the strong Bolton / Preston combination playing as “England” and winning 9-0.

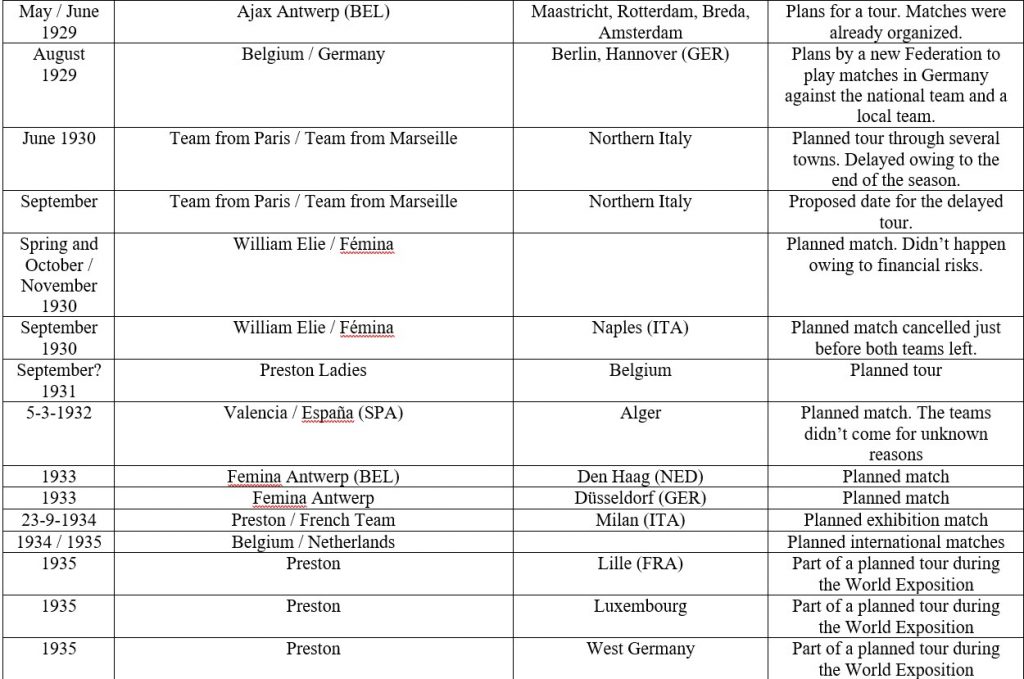

Table 4.20

International matches during WW II

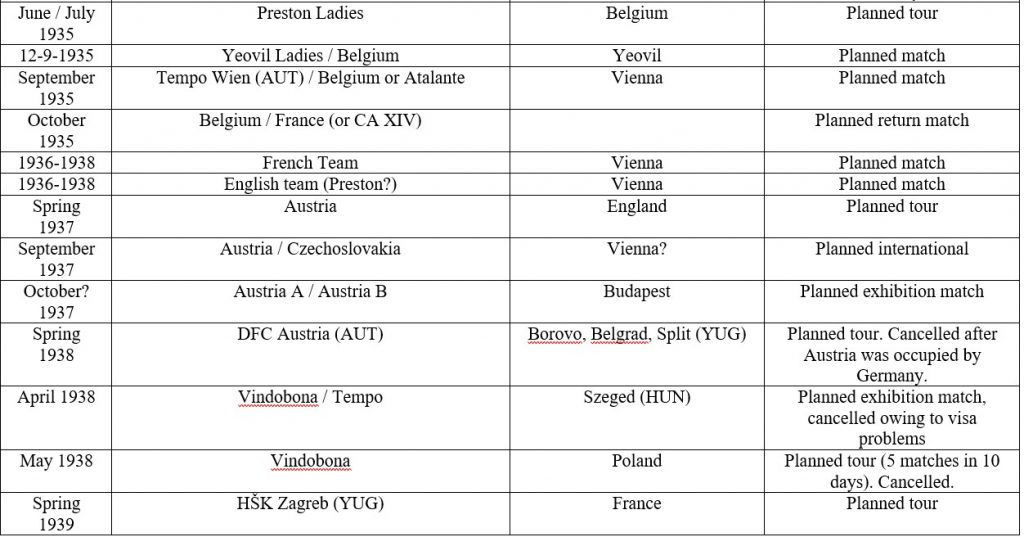

Cancelled Matches and tours

There were quite a lot of matches and tours that didn’t happen. Dick, Kerr’s / Preston Ladies for instance didn’t tour Sweden in 1921, the Netherlands, France, Switzerland and Italy (together with France) in 1922, Ireland in 1925 (again with France), Belgium in 1931. They also didn’t play a proposed match in Milan in 1934 along with matches in France, Luxembourg, Germany and Belgium in 1935 during the World Exhibition.

There was never a match between the French and the Belgium Champion, though in 1930 William Elie (Brussels) and Fémina Sport came very close, when a match at Naples was scheduled but cancelled by William Elie at the last moment. French teams also wanted to play in Czechoslovakia (1928, La Clodo) and Northern Italy (1930, teams from Paris and Marseille). Teams from Belgium wanted to play in the Netherlands and Germany (1929 and 1933). One of these matches was planned against the German national team. A full international between Belgium and the Netherlands was planned for 1934 / 1935. In 1924, Brussels Femina Club wanted to play in Austria in May, while the Austrian club D.F.C. Diana wanted to play Olympique de Pantin in September.

Valencia was expected to play España FC de Madrid at Algier in 1932 but both teams failed to come

Source: Estampa 1932-3-28 / Archive Helge Faller

With the women’s football boom starting in Austria in 1935, the clubs and the federation got in contact with clubs and associations across Europe. In 1935, a match between Tempo and Atalante was scheduled. There was also an attempt to play the French national team. A tour through England was planned for Spring 1937, a match against the Czechoslovakian national team and an exhibition match in Budapest were planned for autumn 1937. Finally, in 1938, tours through Yugoslavia and Poland were planned as well as further exhibition matches in Hungary. The club HŠK Zagreb had plans for a tour through France in 1939.

The reason why these matches and tours never happened were multiple. In several cases the financial risk was too high (like in September 1920, when the French national team was to play Ireland, but the organization committee finally cancelled the plans as the guarantee fee of £600 to pay the French expenses was too high). Austria had the problem of not having a suitable ground, so all plans to play teams from France, Belgium or England didn’t materialize. There were bans by the national federations, who forbade matches by women (like in Belgium in 1922 and Sweden 1921) or the political situation didn’t allow any further women’s matches (like 1938 in Austria and 1939 in Yugoslavia). The possible full internationals that didn’t happen were England vs. France (1922), Belgium vs. Netherlands (1934-1935), Austria vs. Belgium (1936-1937) and Austria vs. France (1936-1937). Also, some semi-internationals were possible: Ireland vs. France (1920), England vs. Ireland (1922), England vs. Netherlands (1922) and Austria vs. Czechoslovakia (1937).

Table 4.21: Proposed international matches and tours

The different cultures of women’s football

There was not just one form of women’s football in the inter-war years. In England several forms coexisted. The most common were the exhibition and charity matches by clubs like Dick, Kerr’s, Hey’s, Yeovil, Darlington and Terry’s. Then there were “fancy dress” matches during local carnivals, mostly women vs. men. Finally, there were organized matches like the ELFA-cup. The strength of the English clubs in the first half of the 1920s was astonishing, but after 1925 Dick, Kerr’s / Preston Ladies was the only club at international level. On mainland Europe there was either the organized or the exhibition form. France and Belgium in the 1920s and 1930s, as well as the Netherlands, Austria, Yugoslavia and others played football in its organized form.

The comparability of the teams

Though international matches were played in most parts of Europe, it is difficult to judge about the strength of the teams. Dick, Kerr’s / Preston, the self-declared “world champion” never played teams from middle and eastern Europe. In the early 1920s, they were without any doubt the best team in the world after some impressive wins against the French national team. But since about 1922-23, there were other teams comparable to the strength Alf Frankland’s team and sometimes even better. The only time Preston played the French national team after 1921 was in 1935 when they lost 2-6 and 1-2 to an impressive French side. France, on the other hand, won most of the matches against Belgium. But what about the Dutch women footballers or the women from Austria? Film documents are rare, but they help to get an idea of the level of Dutch and Austrian women’s football compared to England. Judging from this evidence it can be said that Preston would have had a hard time playing the Austrian national team or even the best club sides like D.F.C. Austria or Ö.D.F.C. Wien. The teams in Austria played more matches during 1936 and 1937 than any clubs in any other country world-wide. The duration of a match was 80 minutes (10 minutes longer than an ordinary match in England and 20 minutes longer than in France and Belgium). The latter two also had special rules like a smaller pitch and a lighter ball. The teams from the Netherlands played some good football too and were probably on the level of Belgium. The Czechoslovakian and Yugoslavian teams were also most probably on the level of the teams from the Netherlands.

The predecessor of modern women’s football

The women who played during the inter-war years were the ancestors of modern women football, especially in the developed countries in mainland Europe. They played organized football that included full internationals, national championships and cups. There were even some international competitions. France, Belgium and Austria had more influence in the development of women’s football than the British clubs, as their aim was to propagate women’s football in their neighbouring countries and playing football in a more serious form. Of course, only a handful of clubs played football in these countries and there may have been no country where more than 500 women played football on a regular basis. But they played, despite bans from the regular football grounds by the male federations (like in Belgium, Austria and, of course, England) and the big reservations of public opinion against women’s football. The astonishing fact that international women’s football matches between ca. 1920 and 1940 were the rule and not the exception should change the way we view women’s football during these times. Modern women’s football started during the inter-war years.

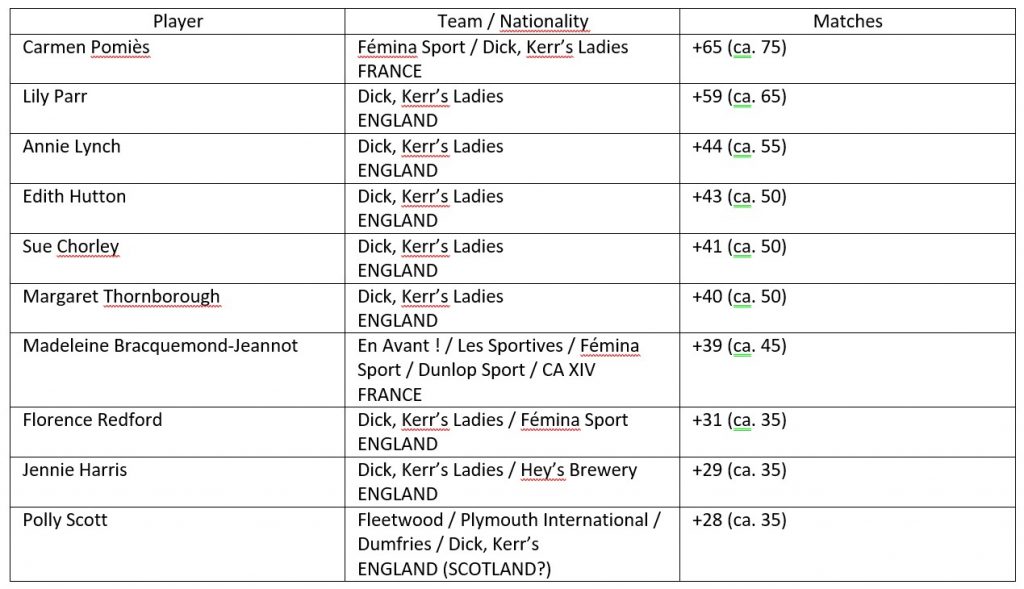

Tables.4.22-27: Record players in international women’s football 1917-1941

Table 4.22

Most international matches

a “+” indicates that the player has played more than the currently known matches

The number in brackets is the estimated number according to the sources

Table 4.23

Most full internationals

Table 4.24

Most international goals

Table 4.25

Most goals in full internationals

The scorers of the 1933 match France vs. Belgium 3-1 are still unknown

Table 4.26 Most matches by country

a “+” indicates that the player has played more than the currently known matches

The number in brackets is the estimated number according to the sources

Table 4.27

Most goals by country

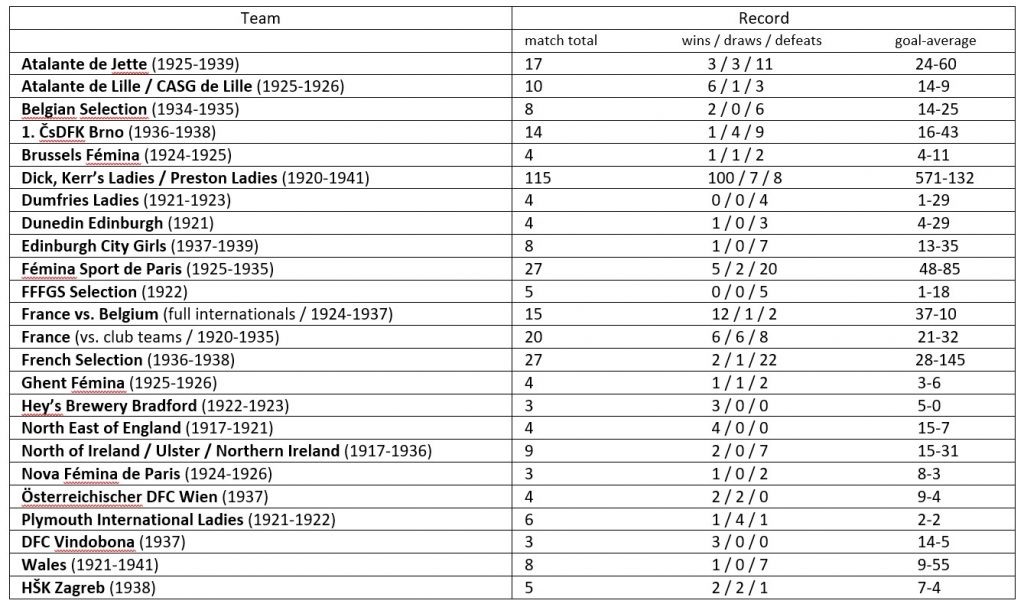

Table 4.28

Records of clubs, selections and national teams with three or more international matches

Article © Helge Faller 2021

Acknowledgements:

The author would like to thank Patrick Brennan, who has done pioneering work in the research of women’s football before 1945, Stuart Gibbs for his great help in researching several international matches of the 20s by Dick, Kerr’s / Preston Ladies and invaluable information on Scottish women’s football during the interwar period, Xavier Breuil for some very helpful remarks on the F.S.F.I., Stipica Grigić for providing some very helpful remarks on Yugoslavian women’s football 1937-1939, Matthias Marschik for his tremendous support and Achim Trapp for reviewing the text.

Annotations (for a more detailed list contact the author):

- L’Auto 4.1933, La Dernière Heure 10.1932, 4.1933

- See “The Female Pioneers – A Statistical record of Women’s Football in Great Britain & Ireland from 1881-1953” (3 Vols.) by Helge Faller (2021, Les Sports et la Femme)

- La Dernière Heure 4.1934, L’Auto 4.1934, “The Female Pioneers”, “De eerste Voetballerinas” by Helge Faller (2017, Les Sports et la Femme), And then we were boycotted – New discoveries about the birth of women’s football in Italy (1933)” by Marco Giani (2019-2021, Playing Pasts) – definitely the best work on early Italian women’s football with an abundance of phantastic photographs and stories about the players. “Trollkar som tränare” by Klas Palmquist (2011, https://torgetbloggen.blogspot.com/2020/05/50-kilosflickor-mot-100-kilosgubbar.html)

- L’Auto 3.1935, 4.1935, “The Female Pioneers”.

- “The Female Pioneers”, Part of the Game – The first Fifty Years of Women’s Football in Ireland and the International context” by Helge Faller (2021, pp 58-84 in Studies in Arts and Humanities 7 (20021) 1, “Eine Klasse für sich – als Wiener Fußballerinnen einzig in der Welt waren” by Helge Faller & Matthias Marschik (2020, Verlagshaus Hernals)

- “Eine Klasse für sich”, “The Female Pioneers“, l’Auto 5.1937.

- “Kratka povijest ženskoga nogometa u Hrvatskoj/Jugoslaviji u međuratnom razdoblju” by Stipica Grigić (2018, DOI: https://doi.org/10.22586/csp.v50i3.115), “Eine Klasse für sich“, “The Female Pioneers“.

- “The Female Pioneers”

![Switching from Women’s Football to Cross-Country: <br>The History of Gruppo Sportivo Giovinezza [Milan, 1933-37]](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/PP-banner-maker-440x264.jpg)