Nineteenth century leisure entrepreneurs made reference to aquatic mythologies in ‘selling’ commercial swimming to the working classes. Folklore suggested that water possessed curative powers, creating a demand for health tourism in seaside resorts such as Blackpool. The existence of mermen, mermaids, sea ogres, nymphs, naiads, and river sprites was universally accepted by a population steeped in urban myths.

Source: Judy or the London Serio Comic Journal, 6 September 1882, 109.

The Baths and Wash-Houses Act of 1846 provided Lancashire’s labouring classes with the means to bathe their bodies and launder their clothes. It was one of the first health reforms to provide urban-industrial communities with the opportunity to ‘take the cure’ in municipal public baths designed to improve the physical and moral condition of the poorer classes. A bye-product of this sanitary reform was the incorporation of swimming facilities in public baths establishments. This was a practical solution to concerns regarding the financial burden being met by local ratepayers.

Reference to Blackpool’s Mermaids and Mermen provides context for a conversation with regard to the popularity of commercial swimming as a sport, leisure entertainment, and recreational activity in the new Victorian leisure age of mass entertainment. It establishes a link between swimming as a competitive sport that underwent a process of commercialisation at aquatic leisure venues throughout the UK. Commercial swimming, in common with sports such as association football, boxing, pedestrianism, league cricket, and rugby league grew in popularity with the Victorian labouring classes. Factors such as competition, expertise, aesthetics, and entertainment-value offered access to popular leisure activities.

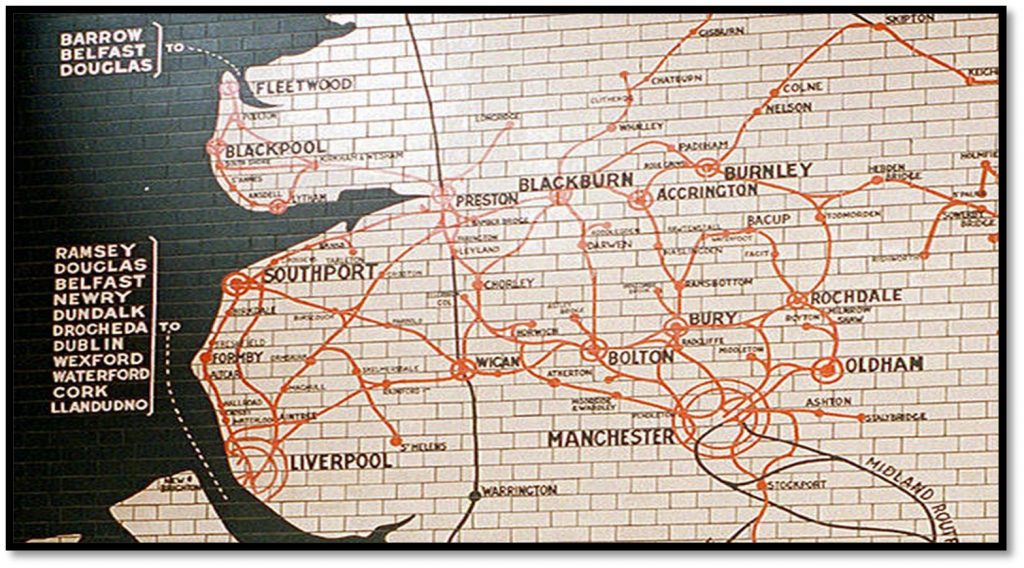

Aquatic leisure venues at seaside resorts such as Blackpool promoted commercial swimming, performed by Natationists, as family entertainment. Commercial swimming was varied in nature and could be performed in both open- and closed-water venues. Elite Natationists transferred the skills learnt at their local municipal swimming baths to Grand Water Shows and swimming club galas. Contemporary newspapers of the period carried reports and advertisements promoting a variety of aquatic performances. As a mature industrial society, Lancashire’s labouring classes were seeking sport, leisure, and recreational distractions from the worst excesses of their urban-industrial environment. As a result of improved living standards, a skilled and comparatively well-paid work-force had more disposable income to spend as a family unit. Rail links promoted the transportation of people as well as goods; it was the age of the excursion train.

Location: Manchester Victoria Railway Station

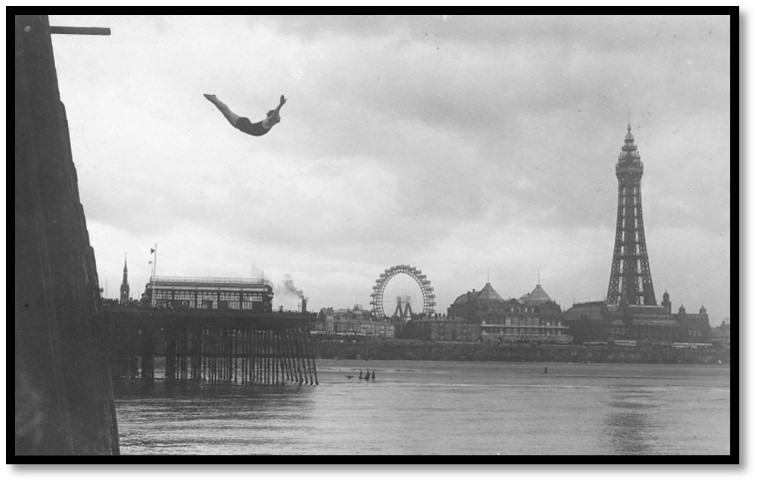

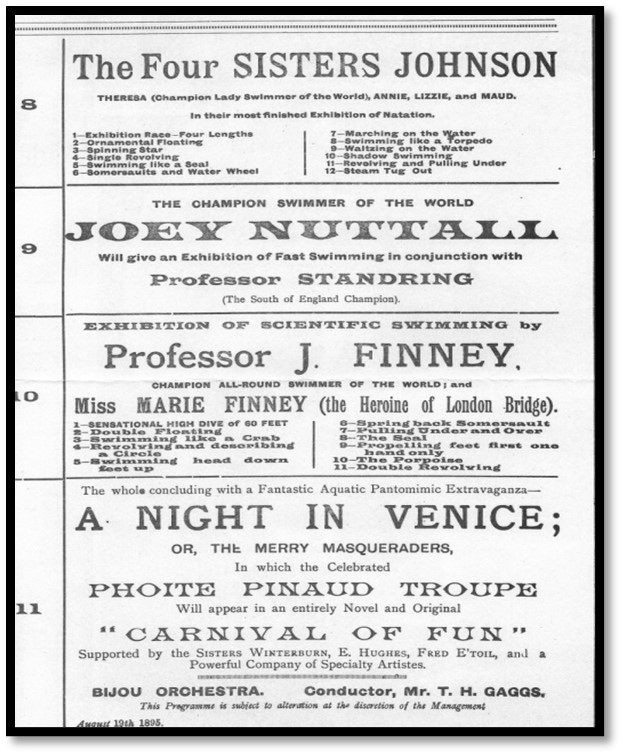

Commercial swimmers performed as family troupes or as individual male and female performers. There were 5 modes of entertainment to amuse spectators: first, exhibitions of swimming strokes and life-saving demonstrations were very popular. Second, competitive races for an ‘aside’ purse enabled spectators to bet on the outcome. Contests were conducted either indoors or outdoors as speed or endurance races from 100 yards to 7 miles. Third, aquatic events often included demonstrations of Ornament or Scientific swimming, now called artistic or synchronised swimming. Fourth, in order to extend the season, ornamental swimmers would perform a variety of feats in glass-fronted water tanks that were either built into the theatre stage or could be wheeled onto the stage at music halls or variety theatres throughout the UK. Fifth, feats of high-diving were also very popular, often executed off high platforms constructed on seaside piers or from bridges over open water.

Location: Harry Crank diving off the North Pie

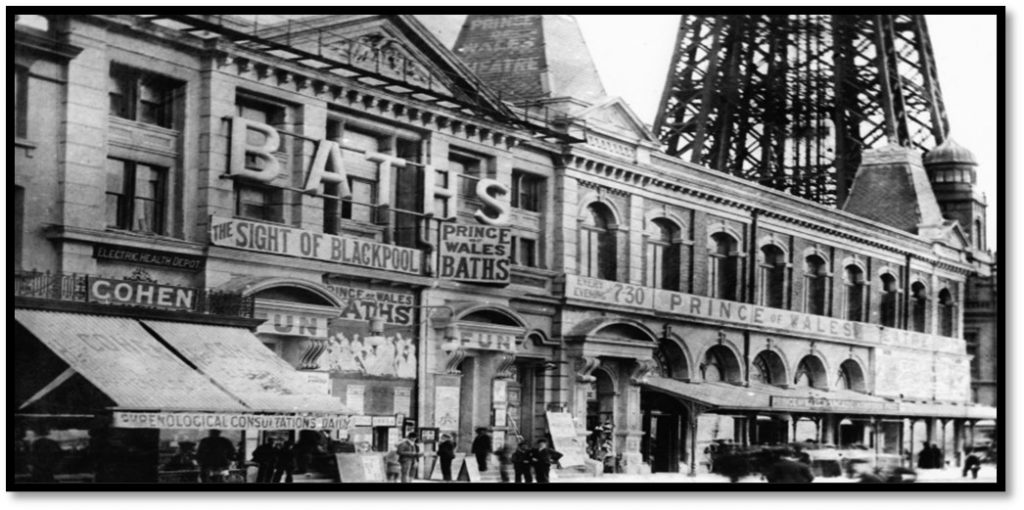

Leading exponents of the art were adept at promoting themselves as ‘penny capitalists’, leisure entrepreneurs, and entertainers. Natationists were engaged by swimming clubs and aquatic leisure venues at local and national swimming galas, seaside resorts, and overseas. Blackpool became the centre for commercial swimming in the final quarter of the nineteenth century with several aquatic leisure venues of the highest quality. The Prince of Wales Baths and Aquatic Theatre (1881-1896) promoted ‘The Greatest Swimming Show in the Universe’, presenting aerial acrobats, ornamental swimmers, and a water pantomime finale 2 or 3 times a day.

Source: Blackpool Gazette and Herald, c.1895

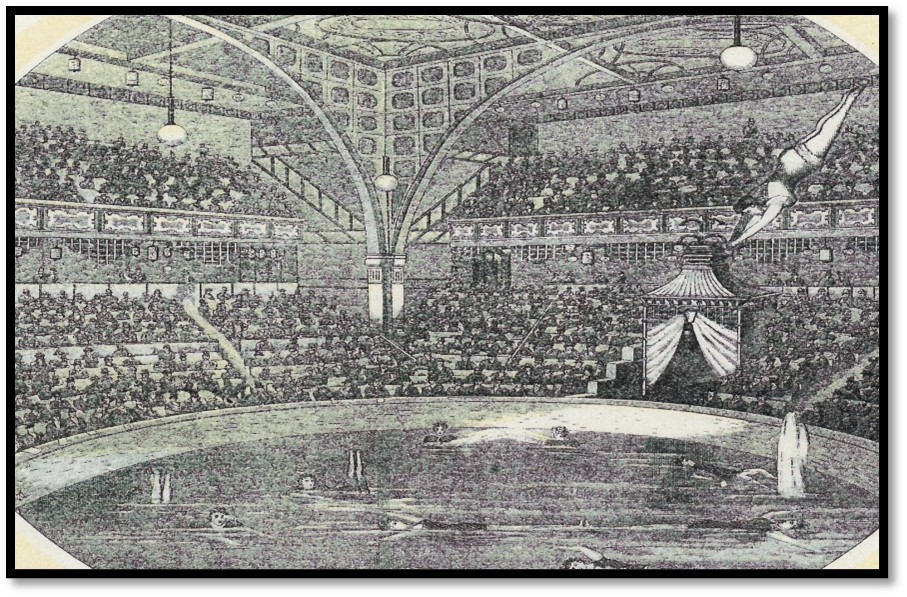

Competition for the visitor’s ‘leisure sixpence’ was intense. Blackpool Tower’s Aquatic and Variety Circus (1894 to the present day) was part of the entertainment offer in direct competition with the Winter Gardens, the North and Central Piers, and the Prince of Wales Baths. The floor of the circus ring was lowered 6 feet to the bottom of the water tank for the last four acts on the circus programme. The Tower Circus was able to entice the best commercial swimmers away from the Prince of Wales Baths by paying them larger salaries and providing better facilities.

Source: Blackpool Tower Company, 1895 Tower Circus Programme.

The leading exponents of ornamental swimming in Lancashire were James and Marie Finney; John and Theresa Johnson (and her sisters); and, Joey Nuttall the ‘Stalybridge Merman’. A plethora of other male and female swimmers also performed at Blackpool’s aquatic leisure venues largely as supporting acts throughout the summer season.

Source: Blackpool Tower Company, 1895 Tower Circus Programme.

In the mid-nineteenth century Blackpool became a holiday destination for Lancashire’s working classes. The direction of growth in popular entertainment for the masses was expressed in the provision of a variety of leisure venues in the mill-town employees’ favourite ‘playground’ of Blackpool. With typical industry and efficiency the Victorian leisure entrepreneur provided variety entertainment in Blackpool’s purpose built leisure venues at a cost that provided value for money. Commercial swimming was an integral part of the entertainment offer in the late-Victorian era.

Source: Blackpool Gazette and Herald, December 1901.

Article © Dr Keith Myerscough