Bicycle racing in the nineteenth century coincided with the mass production in the 1860s of the assisted ‘velocipede’, which was to become known as the high-wheeler, the ‘Ordinary’ or the penny-farthing. Cycle racing gained popularity as a spectator sport initially in France and the United States before spreading to Great Britain. While working-class women’s sport was long established, female participation in cycle racing was limited by societal attitudes. It was thus viewed as the preserve of men, a demonstration of manliness and masculinity on two wheels. However, it was in France, a country that led the way in velocipede manufacturing and racing particularly during the years 1867-1870, that these norms were challenged. The first recorded women’s race took place on 1 November 1868 at Parc Bordelais in Bordeaux, involving four women. Le Monde Illustré provided a brief report on the race won by Mademoiselle Julie who had used “superhuman effort” to beat Mlle Louise, whom had led from the start, with Mlle Louisa finishing third and Mlle Amélie fourth. The correspondent described the women’s attire as “foolish” with an accompanying sketch of the women racing, their clothing flowing behind them due to the speed and their naked legs on full show. The same sketch was reproduced the following month in the American journal Harper’s Weekly, A Journal of Civilization, but was considered too risqué in its original form with the artist covering the women’s legs with undergarments. The following year, on 7 November 1869, saw the first major French road race covering 123 kilometres (76 miles) from Paris to Rouen and organised by the owners of the newspaper Le Vélocipède Illustré with the bicycle manufacturer Michaux. The race was won by Englishman James Moore, but of the 120 entrants and 33 finishers, at least three competitors were women. One English woman calling herself ‘Miss America’ finished in 29th place, some 12 hours behind Moore.

- Le Monde Illustré’s depiction of the first women’s cycle race in Parc Bordelais, Bordeaux. Source- Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF)

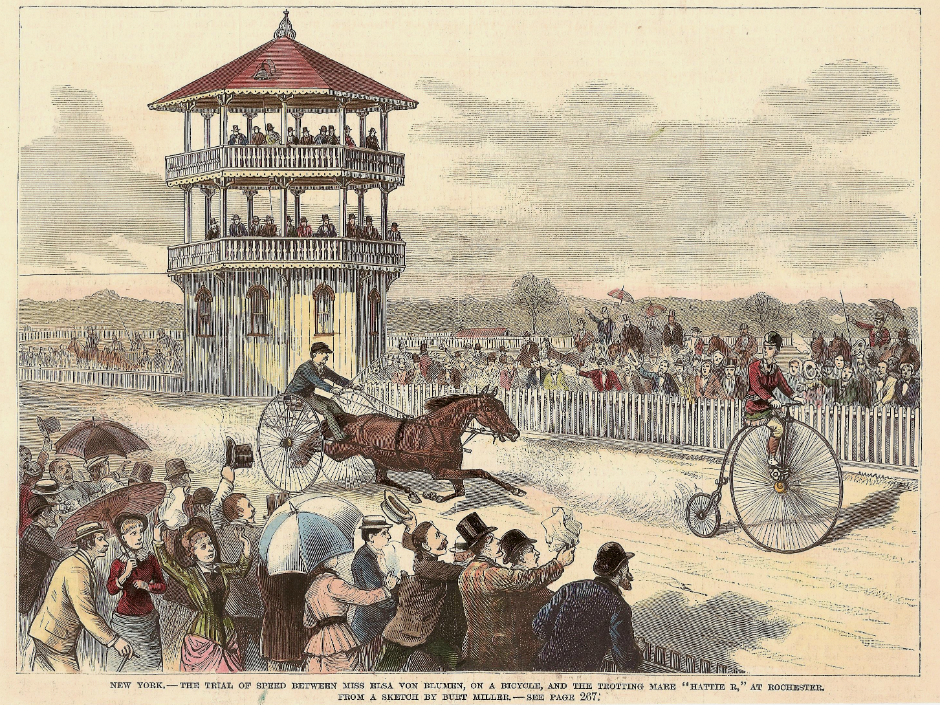

The US was the second country to adopt women’s cycle racing and can be considered the pioneers of the sport in the way it delivered races and encouraged, perhaps unwittingly, a near level playing field between the genders. It also fostered significant press interest with regular reports of the racing that were often picked up internationally, making the female riders stars of the cycling world. However, the activity was initially for spectacle and novelty value. Already an accomplished and much publicised endurance walker, Elsa Von Blumen (real name Caroline Roosevelt née Kiner) was one of the first American ladies to gain cycling fame when she raced a horse named ‘Hattie R’ in front of 2,500 spectators at Driving Park in Rochester, New York in May 1881, just one of many races that she did against horses. The inspiration for this form of racing may have arisen after a visit in June 1879 by Parisian performer Mlle Ernestine Bernard to race a horse over three miles in Toronto, Canada, although male cyclist versus horse had already been popular in Great Britain in the 1870s and subsequently copied in the US.

- Elsa Von Blumen racing Hattie R from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. Source- via Dr M. Ann Hall

Also imported from Great Britain, track cycle racing had become popular in the US during the 1880s and women were regularly participating in handicapped races against men or sometimes attempting individual endurance records on high-wheelers, but also on tandems and even tricycles. Once the racing became established with organisers guaranteed an income through paying spectators, there seemed little appetite for all-women’s races. Indeed, mixed races remained in vogue for much of the 1880s. However, the first women’s race in the US, covering five miles, may have been in Boston on 29 April 1882 between Ida Blackwell and the Canadian-born Louise Armaindo (real name Louise Brisbois/Brisebois), who had also dabbled in pedestrianism and emerged as Von Blumel’s major cycling rival. The first encounter between these two women was a six-day race at Ridgeway Park, Philadelphia on 17-22 July 1882 with Armaindo winning overall. These races though may have set the wheels in motion for further all-women events. The Evening World in May 1889 provides one report of an all-women track race. Entitled ‘Beauty on Wheels’, it details at length a 48-hour race at Madison Square Garden, New York, involving “eight beauteous maidens, fair to see” thrillingly racing for prize money in front of 8,000 fee-paying spectators and accompanied by rousing music from a regimental band.

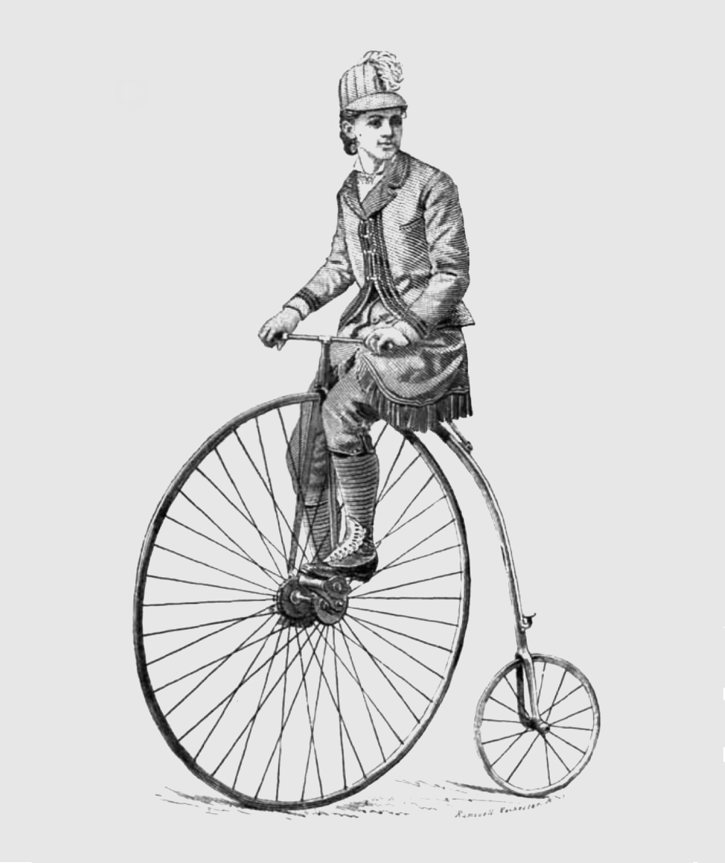

- A sketch of Elsa Von Blumen with her high-wheeler bicycle from 1885. Source- Local History & Genealogy Division, Rochester (NY) Public Library

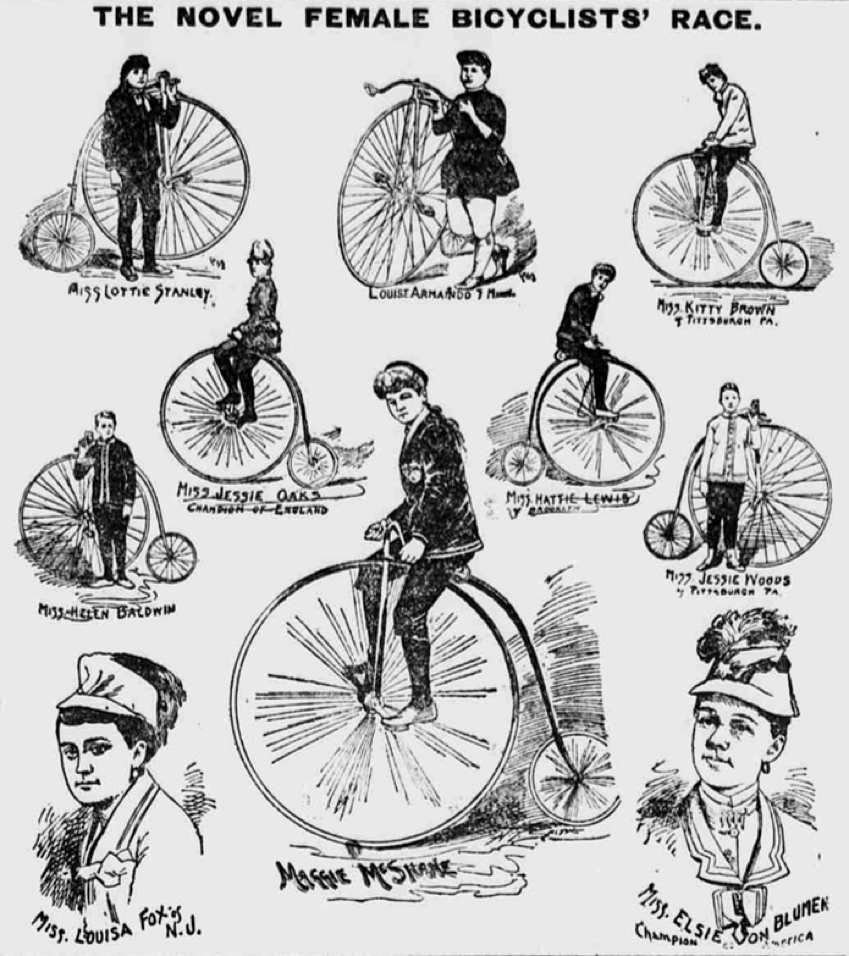

Five of these American stars – Armaindo, May Allen, Lottie Stanley, Lillie Williams and Jessie Woods – were specially brought to Great Britain from September 1889 through to January 1890 for a tour of women’s cycle racing around the country. The first race involving four of the riders (Armaindo was reported to be ill) was held at the Belgrave Road Grounds in Leicester on 24 September 1889 in front of 1,000 spectators, comprising half-mile, mile, five-mile and scratch races. Further races then followed at Grimsby, North Shields in Northumberland, Long Eaton in Derbyshire and Northampton. The tour highlight was two six-day track races, comprising an 18-hour race at the Skating Rink in Sunderland between 2-9 November and a 20-hour race at the Artillery Drill Hall in Sheffield between 20-28 December. A final 100-mile race was held at Sheffield on 31 December 1889-1 January 1890 and billed as “Men v Women” with four of the women (Allen, Stanley, Williams and Woods) pitted against four English male cyclists. It is worth noting that this event also included a five-mile running demonstration by professional runner James Edward ‘Choppy’ Warburton, a man who would loom large in the British and French racing scene in the mid-1890s as both a coach and race organiser. Following this first demonstration of women’s cycle racing in Great Britain, Lottie Stanley remained behind to undertake a further tour individually, racing against male cyclists in May-October 1890 at Cramlington, North Shields, Hartlepool, Llwynypia (Wales), Stoke-on-Trent and Wolverhampton. At one event held at Wolverhampton Wanderers Football Club’s Molineux ground on 26-28 May 1890, it was reported that 17,000-18,000 spectators watched the racing with many there to see the lady racing cyclist out of curiosity.

- A newspaper sketch of some of the American female racers. Source- Library of Congress Newspaper Archive

Women-only races also took place in Australia at the Ashfield Recreation Ground, New South Wales on 23-25 February 1888. These were held in conjunction with men’s races, but the women’s events took top billing in newspaper advertisements, which described it as “The Greatest Success of the Age”. The Sydney Morning Herald called the races “amusing”, while the Sportsman said it was “a novelty”. Melbourne’s Leader was more damning, stating that “bicycles were never made for ‘ladies’ to race upon, and such contests are merely exhibitions which tend to bring discredit on legitimate sport.”

Women’s cycle racing underwent a renascence in the mid-1890s just as the biggest advancement in bike technology took place – the development of the chain-driven safety bicycle with pneumatic tyres. This modern design was soon adopted in track cycle racing, enabling riders to ride low, more safely and at much faster speeds.

All-women’s races were held in parts of the Midwest in the US and in France in newly-built velodromes mostly around Paris, while grandiose six-day races were later held in London. More low-key events were also held in Germany, Italy, Switzerland and Spain. This period of racing lasted until about 1902 and again aroused significant public interest as a spectator sport, resulting in a new breed of celebrity ‘cycliennes’, coinciding with but entirely separate to the boom in women’s leisure cycling at the time.

Article © Mike Fishpool