For Part 1 of this series click HERE

The Rome Hockey Club matches

To make its business known, the RHC chose to organize an annual match at Piazza di Siena inside Villa Umberto (actually Villa Borghese). At that time, Piazza di Siena consisted of a lawn surrounded by a dirt track of about 370 meters in perimeter, used for running, athletic games, horse races and “concours”. The traditional tall pine trees, the age-old hedges of myrtle and an elegant two-storey chalet, the Casina dell’Orologio, encircled it, as they are today. The spectators took their seats on the well-worked embankments and a wooden grandstand was normally erected to house the authorities. When, in February 1904, Baron Pierre de Coubertin had visited the sports facilities hypothesized for the 1908 Olympic Games (later assigned to London because of the Italian renunciation), King Vittorio Emanuele III, accompanying him to Piazza di Siena and showing it in his magnificence, he called it “a natural stage of perfect beauty”.

- An article by The Roman Herald about horse races at Villa Umberto.

The first annual public exhibition of the Rome Hockey Club was set for Thursday afternoon on 26 April 1906. The event was presented as “of particular interest” for local sports clubs. The ladies of the “honorary committee” gave away a richly decorated silver trophy, plus an artistic parchment drawn by the Countess Del Bono of Santa Chiara. The match was arbitrated by Mr. Bethell in the presence of a large group of guests, including many nobles and embassy or military personnel. The match lasted two times of thirty-five minutes each and proved to be very tight. Both teams, the “Reds” headed by the officer of Marina George Astuto of the Lucchesi-Palli dukes, and the “Yellows” captained by Count Ernesto de’ Fiori (both already footballers in Roman FC, the football club born on the same background), proved to be worth the social motto: Never give up! It was decided by Astuto’s goal a few seconds before the final whistle. So everyone, the players and their friends, approached the rich tea-table set up by the committee ladies on the lawn adjacent to the Casina. Among the fumigating cups, the club president handed the cup to the winners. A typical picture of British sport transported in its entirety to one of the most suggestive places in Rome.

In 1907 and 1908 the “annual match” probably took place in the social field, and no references were left in the news. In the summer of 1908 the field hockey was for the first time included in the program of the Olympic Games, with a restricted participation in six British, German and French men’s teams. May be on the basis of this fact, in 1909 the leadership of the RHC again succeeded in inserting it into a public event, the “June Sports Parties” (Feste Sportive di Primavera), a kermesse of competitions and gymnastic exhibitions under the aegis of the National Institute for Increment of Physical Education.

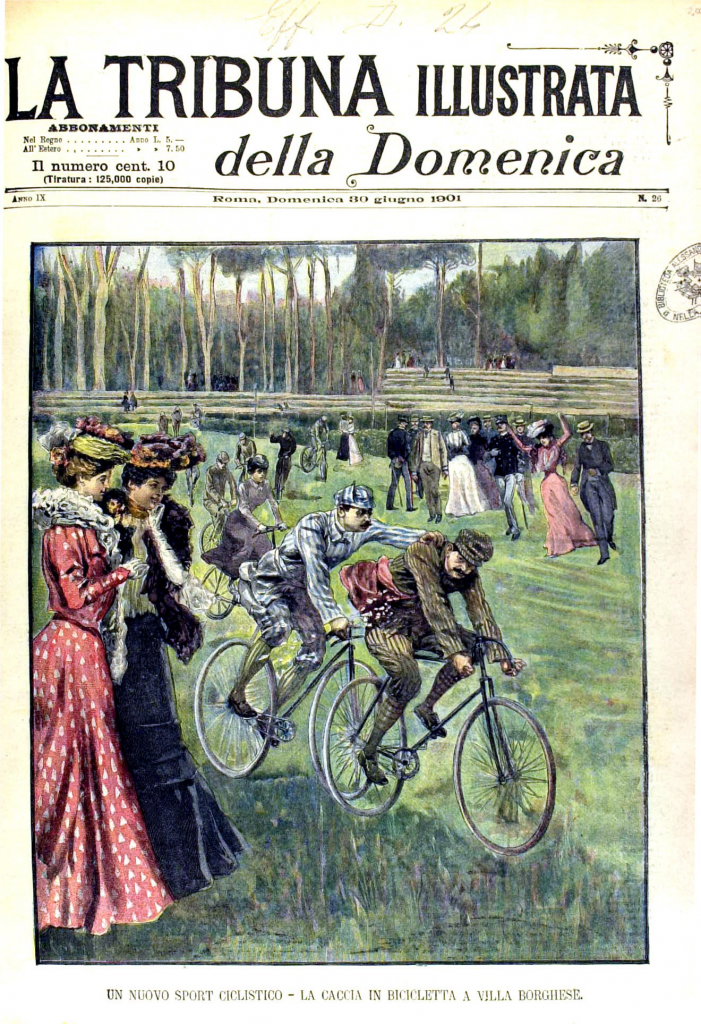

On Thursday 10 June 1909, in Piazza di Siena flocked and crowded, with military bands deployed and paid entry, the highlight of the day was the final of the soccer tournament. The Gymnastics Society “Andrea Doria” of Genoa defeated 2-0 the Podistica “Lazio” of Rome. Afterwards, at 6:20 pm, the members of the Rome Hockey Club entered the field for their performance. Two teams, each of eight male players and four female players, despite their goodwill, failed to attract the interest of the public that had just witnessed football. After two times of the total duration of forty minutes, the game ended on 1-1. This time there was not even the opportunity of a tea-party, as the square, as planned, was invaded by the relays of the Audax Ciclistico, a national federation that organized long-lasting bike rides.

-

Piazza di Siena, June 10, 1909:

Rome Hockey Club a few minutes before the starting of their exhibition match.

This image was taken by the daughter of one of the protagonists, Misses Giulietta Schiavetti from Fiume.

It was first reproduced as a curiosity in the federal magazine “Hockey Club” in 1982.

In 1910 the Rome Hockey Club declined the invitation to participate in the June Sports Parties. His activity closed in 1911, when the Libyan war brought the country into a new fervor of colonial conquests and several club members were called to arms. With its public initiatives, the RHC had made itself known to the media. Even one of the most famous Italian journalists, Emilio Pons, in his Encyclopaedia Sportiva published in Milan in 1909, spoke of field hockey as a sport «very played in Rome». According to him, the Roman nobles had imported it from France, where the game had quickly made devotees coming from England. A path, this England-France-Italy, classic for many other sports disciplines. Boxing and rowing, for instance.

Field hockey then arose in Rome in the early 1900s. He took his first steps in an elitist, international context, and with the addition of sexual promiscuity. It lasted until the Italian-Anglo-American movement that gave it life did not exhaust enthusiasm. So it literally disappeared, to the point that in the mid-30s the fascist hierarchies realized that Italy would be present at the Olympic Games in Berlin in all sports less three: field hockey, handball and polo. Fascism immediately intervened, reviving field hockey in particular from its ashes Belle époque. In 1936 field hockey became part of the specialties controlled by the then Italian Roller Skating Federation, founded in Milan in 1922 with the presidency of Alberto Bonacossa. Thus the Federazione Italiana Hockey e Pattinaggio a Rotelle was born, which until 1943 was, according to Lando Ferretti, one of the powerful sports leaders of the time, the federation that made the greatest progress starting practically from scratch.

-

The Rome Hockey Club playing at Villa Umberto.

La Tribuna Illustrata June 20, 1909.

At this point, some questions arise that deserve further study. Why did the curtain fall for twenty years on Italian field hockey? And at a time when all other sports, even the most bizarre and unknown, were proposed to the social system? Can we hypothesize that the originality of the initial choices influenced this very special course? It may be thought that the wave of militarism that took hold, like a fever, of the Kingdom of Italy since the war in Libya and reached its peak in the first world war, with political movements little inclined to feminism such as the nationalist one, is it at the base of the setting aside of field hockey, an exotic sport that had had the audacity to run and play together men and women armed with sticks on a grassy field in front of an audience?

In our opinion, fascism, almost unconsciously, considered the sport of field hockey as more suitable for women and therefore negligible, since it was born in Italy as a transgender discipline. That a woman “beat” a man in public and even the opposite could happen, seemed unacceptable and not codable. If not in the Carnival period.

-

La Tribuna Illustrata della Domenica, June 1901

It is about a “papere-hunt” held at Villa Umberto.

Article © Marco Impiglia

![Playing Football with the Chorus Girls: <br>Vaudeville Women’s Football in Naples [1931]](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/PP-banner-maker-440x264.jpg)

Fascinating pair of articles. My great aunt Win Spink was accepted as a member of the Rome Hockey Club in Nov 1906, soon after she went to Rome – she was a keen hockey player, and knew Helen Ravi (treasurer). Her first paid work was as tutor to Mrs Astuto – “Astuto” recorded the winning goal in the public match described in Part II.