To read Part 1 – click HERE

1923 was a crucial year for Austrian weightlifting and one which relied on the Viennese athletes. A new generation of weightlifters performed well in the Gothenburg International Games and in the World Championships in Vienna, not recognized at the time by the International Weightlifting Federation (Fédération internationale d’haltérophilie, IWF). In addition, a workers’ weightlifting federation was formed, joining the Socialist Workers Sport International (SWSI) and numerous weightlifters of excellence migrated to the Socialist-inspired Österreichische Arbeiter Athletenbund, (Austrian Federation for Worker Athletes, ÖAA). Finally, the association of veterans of heavier athletics (Alte Wiener Athleten, AWA) was born and was responsible for promoting competitions, awarding prizes, and preserving the memory of Viennese weightlifting. As part of its inaugural events, the AWA visited the graves of Stöhr and Türk, who both died in 1920.

At the Paris Olympics of 1924, Austria obtained four medals all in weightlifting, three silver (Stadler, Zwerina, Aigner) and one bronze (Friedrich). Was that enough to renew Vienna’s reputation as a city of the strongest men? Apparently, the answer was yes. Owing to a complicated rule, which was never adopted again, despite Italy having won three titles and France the remaining two, Austria won the team competition. Although it did not contribute to the Olympic rankings, a cup and medals were awarded to each of the winning team’s athletes. In 1926, Austria formally protested to the French Olympic Committee having not received these awards.

Sport Tagblatt 31 July 1924

Th reported Austria victory in team event

In any case, the myth had regained vigour, the new generation was winning and conquering world records. At the Amsterdam Olympics in 1928, Austria won two gold medals thanks to Andrysek and Haas. The newspaper Illustrierte Kronen Zeitung ran the headline

‘The city of the strongest men triumphs in Amsterdam.’

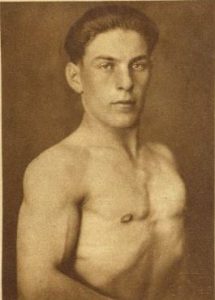

Franz Andrysek

1928 Featherweight Olympic Gold Medallist

The myth was renewed, even though weightlifting was no longer considered to be the national sport and had been surpassed by football, as declared by Sport Tagblatt in 1919. However, the Wiener Mannschaft Meisterschaft (Viennese team events League), which ran at regular intervals for almost a calendar year, was very popular. The capacity of the halls intended to host the matches varied between 1,000 and 5,000 spectators. Empty seats were rare. In 1929, the IWF granted Vienna the honour of staging the first official European Championships. The Viennese won three out of five titles in the lighter classes and Sports Tagblatt noted that ‘Vienna is the city of the lighter strongest men’.

In 1931, Vienna hosted the SWSI Olympics. Austria won all seven competitions of the main weightlifting program and, even in the SWSI, Austrian weightlifters dominated holding almost all world records. However, the Socialist press did not use the phrase ‘Vienna the town of strongest men’ as SWSI’s Austrian weightlifters were considered as flagbearers of Socialism on the march; models for all workers. On seven occasions, SWSI records by Austrian weightlifters surpassed those of the IWF. Enthusiastic fans often wrote to the Arbeiter Zeitung editorial team asking for detailed information and for more frequent publication of records tables. Such titles and records were seen as indicating leadership in the advancement of Socialism and the achievements were often reported with the phrase ‘Arbeiterkfratsportler marschieren auf’ (Workers’ lifters are marching on).

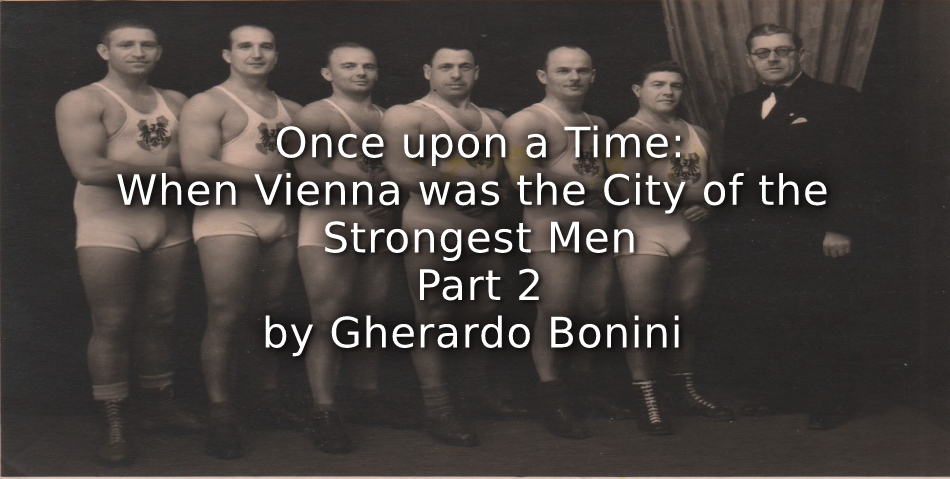

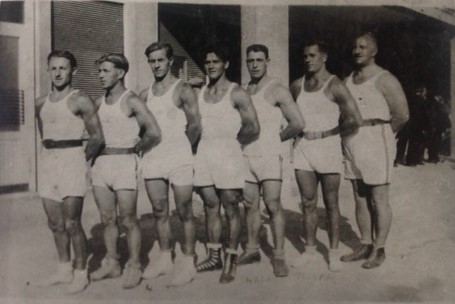

Seven winners of Workers Olympics in Vienna 1931

After the civil war of 1934, SWSI weightlifters re-joined the bourgeois federation, continuing to win. The Kleine Blatt newspaper had been Vienna’s second Socialist journal, but it had to align itself with the regime, although it retained a good number of journalists. Under the title ‘From the city of the strongest men’, from May 1934 to April 1936, the newspaper published over 60 biographical sketches of athletes with the peculiar characteristic of reporting the honours they had achieved in the ranks of SWSI. After all, these victories, too, had contributed to the greatness of Vienna as a city of the strongest men and their memory had to be shared and preserved.

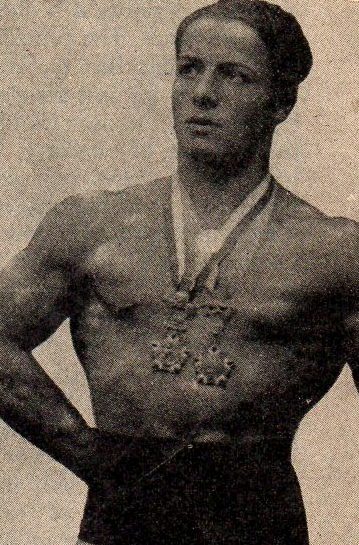

Robert Fein was the last Olympic winner for Austria in Berlin 1936

The Austro-Fascist regime intended to strengthen national identity, reinforcing Nazi pressure in favour of Anschluss. This promotion of a national identity could be seen in reports about Viennese weightlifters. The weightlifters were still considered part of the world elite, but the press, while continuing to indicate their Viennese origins, often began to use the term ‘Austria, land of the strongest men’, as occurred on the occasion of Steinbach’s death in 1937.

Excerpts from Volkszeitung 22 September 1940

Vienna won since the era of lifting barrels

After the Anschluss and during the war years, the sporting rivalry in weightlifting between the Viennese and the Germans remained heated. The press gave free rein to lokalpatriotismus (local patriotism), accentuating this especially after the successes in the German Championships and in the deeply felt clashes between Vienna and Munich – Vienna remained the city of the strongest men. On the other hand, the Völkischer Beobachter, the official newspaper of the Nazi party, underlined an aspect also often identified by the Austrian press, namely the Viennese mediocrity in other athletic sectors linked to strength, including wrestling, judo and throwing.

After the war, faced with a difficult new reconstruction, could Vienna be trusted as the city of the strongest men? The press affirmed that most of the top weightlifters no longer served national socialism and could concentrate on defending the Austrian colours. However, the Austrian team performance at the Paris World Championships in 1946 was poor and traumatic. Some newspapers, like Welt am Abend or Kleine Volksblatt, crudely reported that Vienna was no longer the city of strongest men, but of the weakest. The myth, so popular before the war, had not been renewed and had been definitively confined to history.

Photo of first post-war Austrian international representatives

The last three on the right are Fritz Haller, Karl Schuster and Anton Richter

All three World record holders in 1930s

Until 1955, Austrian weightlifters achieved some sporadic success in the European field, but at the Olympics and the World Championships they remained far from the best. The press alluded in speaking about a possible renaissance, but then it surrendered to the facts. Foreign competitors were the strongest men and Vienna was left to think about its past. These proud memories remained nostalgically fixed to an era lasting half a century, during which Viennese athletes had produced the greatest number of champions and international records in the world, including the achievements and competitors of the SWSI.

Vienna’s last success was historiographical. Until 1981, the official books of the International Weightlifting Federation only recognized the World championships staring from 1922 and European ones from 1929. A historical commission created by the IWF redesigned the historical framework giving a posteriori officiality to all the World and European Championships of the previous years organized not only by Austria, but by the UK, Germany, France, Italy, Holland, Switzerland and Sweden. No longer just Viennese heroes, Türk, Steinbach, Grafl and Swoboda entered into the official history of weightlifting.

Article © Gherardo Bonini