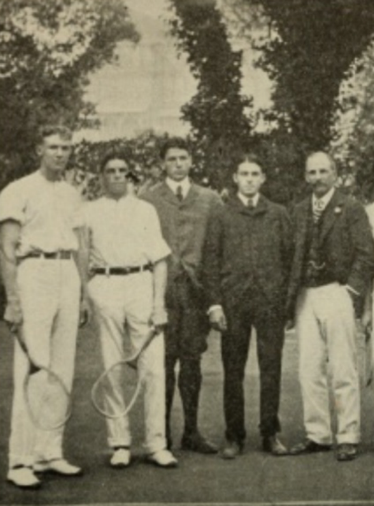

In the summer of 1899, Dwight F. Davis, in the company of three fellow lawn Harvardians: Beals Wright, Holcombe Ward and Malcolm Whitman, ventured across America to challenge the best of the Californian lawn tennis players (Plate 1). On his way home, inspired by the success of his tour, and reading of the success of the American team in the America’s Cup, it occurred to him that, ‘if team matches between different parts of the same country arose such great interest… would not similar international contests have even wider and far-reaching consequences?’. On arriving in Boston, the nineteen year-old immediately sought a meeting with James Dwight, the then president of the United States National Lawn Tennis Association (USNLTA), to present his idea. Davis, many years later, reported that, ‘the idea was approved by the lawn tennis authorities and consequently I offered the International Lawn Tennis Challenge Cup.’

- Plate 2. The trip to California (Malcolm Whitman; Holcombe Ward; Dwight Davis; Beals Wright; George Wright)

This is the story of the origins of the Davis Cup- an accepted account that has persisted for over a century; a chronicle that clearly fits neatly into the country’s emerging outward facing ‘Empire-building’ towards the end of the ‘Gilded Age’. However, Davis’s recollection of events, first expressed in American Lawn Tennis in 1907, may have overplayed his significance, fostering a narrative perhaps more akin to the now famous ‘Doubleday myth’ in baseball. This ‘accepted’ story presents Davis as the central character in the inception of the international game, whilst others, who made equally, if not more, significant contributions, have been ‘airbrushed’ from the history of the Davis Cup.

Charles Voigt, or as he was familiarly known, ‘The Baron’, is one such person- a devotee of lawn tennis, and vociferous promoter of the game in Europe. According to tennis player and writer, Jehail Parmly Paret, he was instrumental in changing the attitudes of the British to their trans-Atlantic cousins, for he, ‘enthused considerably over American tennis players’. William Dana Orcutt, the then Editor of American Lawn Tennis, writing in 1899, highlighted Voigt’s reputation, arguing that ‘no one, perhaps, has figured more prominently, or has accomplished more in the direction of international tennis, than Mr. Voigt, his name being associated with the game in nearly every country.’

- Charles Adolph Voigt with the Doherty brothers

- and with a group of players at Homburg

Charles Voigt’s role in developing the international game has received scant attention, yet for many years, he worked tirelessly in incepting European international matches, and sought to formulate strong trans-Atlantic relations between players and administrators. In 1899, he wrote to the Editor of American Lawn Tennis, the official organ of the USNLTA, promoting ‘the newly founded “Championship of Europe” [which included] 44 entries from all parts of the world’, – importantly highlighting that ‘the English official journal “Lawn Tennis” had presented a 50-guinea challenge cup’. In this letter, Voigt also indicated his desire to instigate team challenges, declaring that American ‘crack’, Clarence Hobart had similar notions. ‘He intends spending the winter at Cannes, and… will leave England [to return to America] at the beginning of August next, especially if he can get a strong English team to accompany him’, wrote Voigt, adding generously, ‘although such a plan would be greatly against my Homburg interests, I am sure I will place nothing in the way’. Voigt clearly had international matches at the heart of his work in Europe, yet when the Davis Cup was inaugurated in 1900; his efforts in initiating the international game were cast aside, in the rapid ‘promotion’ of Dwight Davis, as the sole architect.

Writing in 1912, Voigt – without seeking to undermine the ‘accepted’ version of the inception of the Davis Cup – presented an alternative perspective. He claimed that he had discussed the idea of an international challenge trophy – seemingly similar to the ‘50-guinea challenge cup’ presented by Lawn Tennis – with friends at the Niagara-on-the-Lake international tournament, in July 1896, several years prior to Davis’s apparent ‘epiphany’. According to Voigt’s recollection, he was first introduced to 16-year old Davis at that tournament, although he remarked that their paths may have crossed earlier in the year, at Tuxedo. One evening, on seeing Davis and a young lady leave the ballroom for their walk in the moonlit gardens, he enquired of his company, Edwin “Eddie” P. Fischer and J. Parmly Paret: ‘“Who on earth is that young sport”? “Why that’s our young multi-millionaire, Dwight Davis, of St. Louis”, was the reply.’ Voigt retorted that he had rarely had the good fortune to meet a millionaire, who played lawn tennis, and suggested to his companions: ‘Why don’t you people get him to do something for the game? Put up some big prize or cup?’. According to Voigt, the topic of conversation that evening had been centred on the possibility of international visits and matches, and he had suggested, at this time, that if put correctly before the [British] Lawn Tennis Association (LTA) and USNLTA, ‘the affair would in no doubt soon become a fait accompli.’

- Plate 3. Tennis players at Niagara-on-the-Lake (1896)

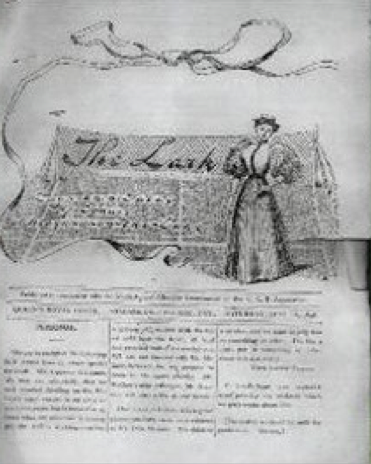

Whilst, Voigt did not speak directly to Davis on this matter, it is incredulous to believe that he was unaware of the discussion that had taken place between Voigt and his colleagues, particularly given the unique nature of the Canadian tournament. The week-long event was for the most part, seemingly, more akin to a holiday outing, than a tennis tournament. It was a highlight of the social calendar, and reports by Parmly Paret indicate that a certain amount of ‘tomfoolery’ existed, alongside a deep-rooted camaraderie, especially within the “Bachelors’ Hall”, an annex to the main hotel, where, ‘all the players are domiciled…during the tournament week.’ Parmly Paret highlighted that the annex was one of the key features of the tournament, where ‘divers and sundry rumours are always in circulation of the dark deeds that take place during the wee hours’. With players living in such a close proximity to each other, it would be impossible to escape ‘Dame Rumour’, and should one miss the nightly gossip, it was avidly repeated in print in the tournament’s daily paper- The Lark. According to Voigt, the editors, Eddie Fischer, Parmly Paret and Scott Griffin ‘would sit up long after the evening revelries to fill its pages with topical matter for each morning’s edition’. Writing later, Paret recollected:

This little sheet comes out about noon every day during the tennis week, and its four or six pages are devoted exclusively to the news of the tournament. For half an hour after it comes out each day, everybody, player and spectator alike, is buried in his copy, for no one knows who will be the next victim of the really clever pens of the editors.

Charles Voigt, reminiscing of the 1896 editions, recalled:

Every occurrence was chronicled next day in “The Lark”, no matter how trivial… It mocked the young Beals Wright, who would play wearing a “spotless high collar”… and also frequently had occasion to refer to the “evening strolls in the shrubberies” of Dwight F. Davis with the belle of the place.

According to eminent tennis historian, Heiner Gillmeister, the report of Dwight’s evening strolls meant ‘it was therefore almost inevitable that the young man from St. Louis, who naturally had a very personal interest in the bulletin’s stories, also became acquainted with what Voigt has said about the Cup’.

- Plate 4. The Lark

Of course, Davis was clearly ‘distracted’, and as such may have missed the nightly revelry in the “Bachelors’ Hall”. He may even have failed to read The Lark, a paper that sold out within minutes of publication, such was its popularity. These are plausible explanations for Davis’s failure to credit the role of Voigt, in neither of his written recollections of 1907 and 1931. However, in examining the player lists at the Niagara-on-the-Lake tournament, it is apparent that ‘friends’ accompanied Davis; two of his three companions on his trip to the west coast in 1899 were present- Malcolm Whitman and Beals Wright, the former even partnered Voigt’s friend, E. P. Fischer in the men’s doubles.

Whether Voigt’s story of the summer of 1896 is the whole or part truth is not possible to ascertain; however, what is evident is that he was sufficiently confident of his version of events to allow publication of the story in one of the foremost lawn tennis magazines of the period: Lawn Tennis and Badminton. Voigt was also at ease in naming others who were involved in his conversations, both of whom were instrumental in producing The Lark. Neither Fischer nor Parmly Paret sought to contradict Voigt, perhaps indicated they concurred with his recollections.

Today, Dwight F. Davis, an inductee of the International Tennis Hall of Fame, remains one of the most iconic names in sporting history. In contrast, Charles Adolph Voigt, despite his considerable efforts in bringing to the fore the international character of the game remains one of the ‘ghosts’ of lawn tennis history.

Article © Simon Eaves & Robert J Lake