Hans Nogler might be defined as an ‘uncrowned king’ of alpine skiing. He never won a World title or an Olympic medal, but, in the memory of fans and experts, he was reputed as one of the best skiers, gifted with a special feel for snow. His story is also interesting because it was deeply touched by one of the most tragic periods of European history, from 1938 to 1945.

Born in Vienna, Austria, on February 28, 1919, he returned with his family to his hometown of Wolkenstein [in Italian, Selva Val Gardena], in South Tyrol, which, following the settlements of Europe after the Great War, passed from Austria to Italy. Later, Fascism began a violent policy of forced Italianization in the region, trying to repress the deep German cultural identity. The names of places were Italianized and the provinces were more suitably organized for the control of the regime; a regime that made learning Italian obligatory in schools and eliminated German from the curriculum. Fascism also attempted to Italianize the surnames of the German people.

Nolger in action in Austrian championships 1949 when he was runner-up

Photograph by Keller

The regime also used sport as part of the policy of Italianization, establishing its youth associations, dissolving the German-speaking clubs between 1925 and 1926, re-founding them with Italian names and compliant officials, and limiting contacts with Austrian athletes, especially North Tyrolean ones. Johann, colloquially known as ‘Hans’, but to the Italian bureaucracy as Giovanni Noggler [eventually ‘Nogler’] soon showed an aptitude for sport and between 1935 and 1936 he competed in ski jumping and cross-country races. At the time, the differentiation between Alpine and Nordic disciplines was not so marked and the young South Tyroleans, like their counterparts from the North, practiced all specialties. Hans’ experiences with ski jumping increased his natural ability to instantly judge the ground and to decide which was the best posture to adopt.

The Italian Ski Championships of 12 February 1937, in Cortina d’Ampezzo, launched Nogler into the national elite. He finished runner-up both in the slalom [known at that time in Italian as ‘compulsory downhill’] and in the downhill, resulting in a second place in the combined standings by only 0.04 points. On the same days as the Italian Championships, the first official races of the 1937 Chamonix World Championships took place and the best Italians competed there. The Italian Championships did not adopt the new international rules on the calculation of the combined event decided by the International Ski Federation [FIS], which came into force in 1936. Were the Chamonix scoring system adopted in Cortina, Nogler would have won the Italian combined title.

Nogler in action at Zakopane 1939 World championships Photograph by Schalbenbeck

In 1938 and 1939, Nogler took five out of six national titles at stake and took part, without great success, in the yearly World Championships. Shortly before the start of the Second World War, in 1939, Nogler was struck by a painful event when he was forced to change his surname. The fascist official and Minister Ettore Tolomei had prepared a handbook where he had marked all [or almost all] the surnames of the area and indicated possible alternatives. They were either translations from the German language or adaptations, which were often ridiculous. Those who accepted the change had the chance to choose an Italianized name without any particular semantic meanings. The head of the family and Hans’s father, Sebastian, a small and slight man, decided on the surname Nano [meaning dwarf, and in German zwerg]. The historian Karl Graf points out that in some regions of South Tyrol, Noggler or Nogler referred to a ‘little man in the mountains’, therefore ‘noggler‘ did not really equate to ‘zwerg‘ and did not have all the diminutive attributes that were applied to it by Fascist ideology. For the World Championships in Zakopane 1939, he remained officially identified as Nogler, mainly due to the time lag in updating the various documents between the Italian federation and those of FIS, Hans himself did not have any influence on the retaining of the older ‘Nogler’ in the Zakopane reports and results sheets.

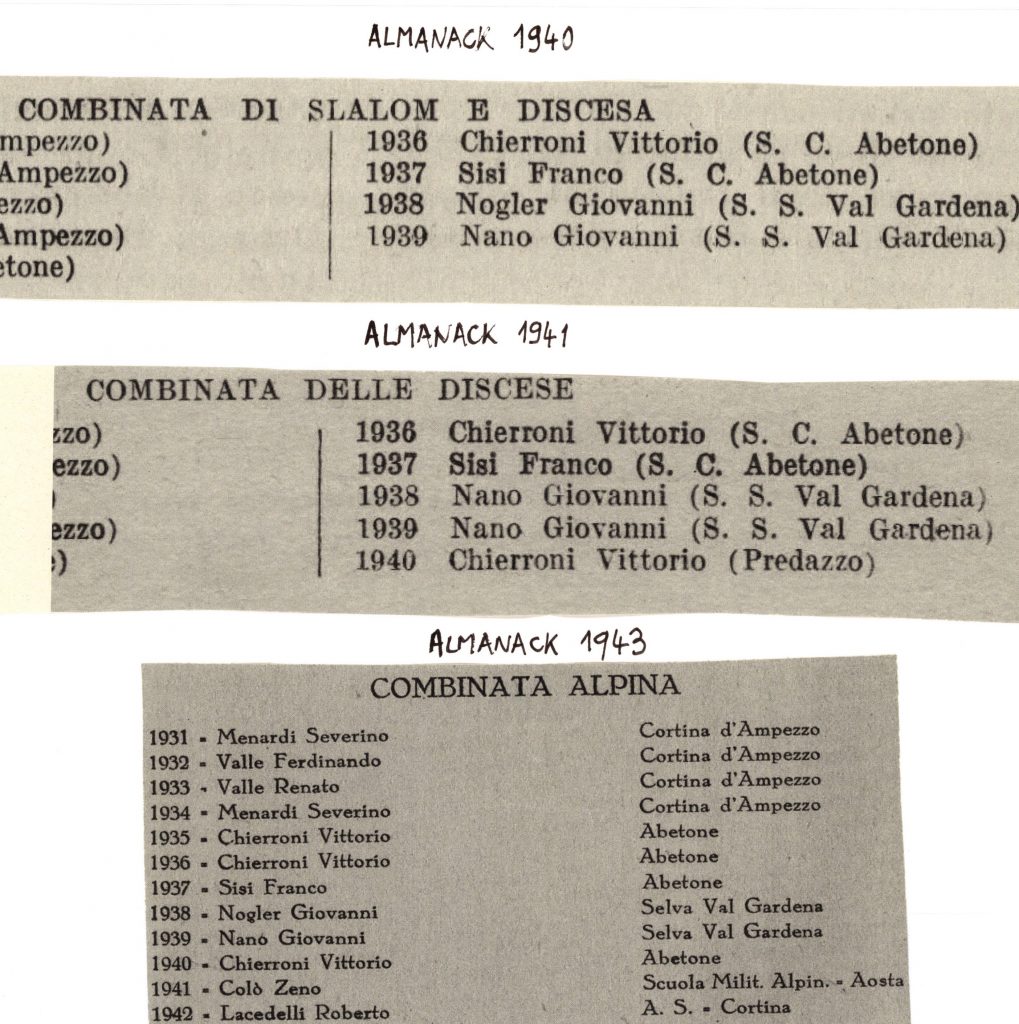

How a propaganda regime glides on communication.

For many years, official almanacs had to manage the fact that ‘Nogler’ is the same person as ‘Nano’, without explaining this in a footnote.

Why were there no footnote?

Because readers might ask why other enlisted winners with German surname did not change the name.

In 1939, the Fascist and Nazi dictatorships made an agreement for the settlement of the South Tyrolean German minority and provided citizens with a choice. Those who wanted to could emigrate to Germany, which had absorbed Austria, where they would find accommodation and work, especially in North Tyrol. Hans Nogler opted for Germany and moved to Innsbruck, joining the German Army, where he he continued his career, under licence. However, he was wounded on the Russian front. In 1944, he won the downhill Championships of Tyrol/Vorarlberg and Germany, where he was second in the slalom and combined events – the standings of this event were calculated on the basis of time. Had the international regulations been adopted, then Nogler would have won the combined event.

After the war, Nogler moved to East Tyrol in Lienz and in February 1946, in Eisenerz [Styria], he won the Federal Meeting, triumphing in the slalom, downhill, combined, plus in ski jumping. The reconstituted Austrian Federation wanted to call the event a National Championships, but, at the last moment, some excellent Tyrolean skiers were unable to participate. Most historians recognize that these victories should be counted as Nogler’s third win in a national championship.

Anneliese Zückert and Hans Nogler winners of Austrian championships 1946

Nogler’s skiing was dynamic and athletic. He made constant use of squats and ran with extraordinary energy, easily falling prey to injuries, which prevented him from regular participation in races. He remained one of the best Austrian skiers and there was great competition in Austria. In August 1947, he won a slalom in Argentina and left a lasting impression, being nicknamed ‘Gummiman’. He won a fourth national honour by triumphing in the giant slalom at the 1949 Turkish Championships. He participated without luck in the 1948 Saint Moritz Olympics and 1950 Aspen World Championships. Shortly after this event, he achieved an extraordinary success in the US Harriman Cup, defeating the Italian Zeno Colò, the World Champion and winner of the Canadian Championships, in the downhill – A Canadian Championships missed by Nogler in order to regain his form. Experts felt that Colò was unbeatable because he was the most daring and fastest skier in the World. However, Nogler also performed well in the slalom meaning that he won both the combined events and the Cup.

Austrian skiers touring Argentina in summer 1947.

Nogler first on the right

From late 1951 until 1956, Nogler found great satisfaction as a ski instructor in Sun Valley [Idaho, United States]. Here, he was recognized as a master, realized his talents and became a role model with American newspapers often praising him and publishing photos of him in action. Once the Salt Lake City Tribune captioned an image with the sentence ‘but when the stakes are high, Nogler used his many skills.’

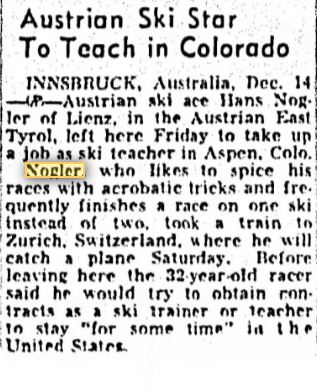

Clip from the Daily Oklahoman announcing the arrival in the US of Hans Nogler, master of acrobatic skiing

Source: Daily Oklahoman 15 December 1951

In 1956, he quietly returned to his true homeland, Wolkenstein, opening a marvellous hotel, the ‘Sun Valley’, which still exists today. Nogler died on May 30, 2011.

Article © Gherardo Bonini

I found this, a very good, sincere, well informed article. The amusing Innsbruck Australia (above) typing slip, gives it just a welcome bit of humour! It gets the happy effect to counterbalance the impossible, stubborn italian habit, in total contrast to the Internationality, to call South Tyrol, which is the original part of Tyrol, still Alto Adige; an expression that could well be used to say that somebody is going to angle, with rod and line, on the upper part of the River Adige, called Etsch in the local Language, Ades by the Trent Romances ( from Latin Ates ( possibly from Sanscrpt “eta” = to rush away, or “Edh” = to become strong, to spread, expanse, swell. Thank You AKB