This article has been written to commemorate the centenary of the death of John Charles Shaw in November 2018. There have been numerous papers and books published containing details of his involvement in the development of the modern game of football within Sheffield and details of matches he played in have been well documented. However, apart from John Steele’s biographical account in The Countrymen which gives some detail, very little is known about the man himself. This article will utilise new material that will give more insight and, it is hoped, facilitate further the debate on the origins of football in Sheffield. The work is an attempt to seek clarification on the existing perspective of the origins of the game and John Charles Shaw’s specific impact on it, as well as to celebrate the overall achievements of the man himself.

In May of 1865, the Barnsley Chronicle ran a story on ‘The Sheffield Football Club Athletic Sports held on the Brammall [sic] Lane Cricket Ground’. One of the events reported was a three mile flat race, open to the Rotherham Athletics Club and all the other football clubs in Sheffield. The favourite was John Charles Shaw representing Sheffield FC. The article recalls, ‘his springy, easy, and steady style of running was much admired’.

During the race, Robert Mason of Rotherham had established a commanding lead, but Shaw gradually started to haul him in. The outcome, however, was that Shaw had left his attempt on Mason too late and came in a close second.

‘From the splendid style in which Shaw ran at the finish, and the rapid gain he made, there can be very little doubt that, had there been another 100 yards to run, he would have won the race’.

The winning time was recorded at sixteen and a half minutes. This would rank amongst elite times by today’s standards. Shaw then went on to win the Mile Race and finally The Stone Picking Race.

‘A really difficult task, requiring considerable strength and agility….. Fifty large white marbles being placed in a line 100 yards long, the marbles being placed two yards apart….. The competitors had to pick up each marble separately and deposit it in a bowl placed at the starting point. The running to pick up these little toys involved the getting over three miles of ground, and in addition to the exertion that had no insignificant task involved, there were fifty stoopings to pick up the marbles. The task was got through by Shaw in 21 minutes and he received a hearty cheer from the spectators’.

John Charles Shaw was 35 years of age and his athletic and footballing abilities were beyond doubt. What has not been so well recorded is his life outside of the sports field.

John Charles Shaw was born on the 23rd January 1830. He was the eldest son of Benjamin and Elizabeth Shaw. The family were residents of Penistone and had been natives of this area for generations. Benjamin Shaw, by trade, was a bespoke cordwainer or bootmaker. He does not appear on the electoral role at this time, or any other time. One can assume from this that he was not a man of property or wealth. Benjamin and Elizabeth went on to have four more children after John (Ann, George, William and Herbert). Further evidence revealing hard times for the couple is shown in the 1861 census. Benjamin was living with son William in Wortley, a village ten miles south east of Penistone. Elizabeth was living as a housekeeper to a relation in the village of Hoylandswaine, together with son Herbert, two miles from Penistone, in the opposite direction to that of her husband. Elizabeth Shaw was the daughter of Giles Shaw and she had been born in Denby, in the parish of Penistone, in 1806. Her grandfather was also named John Shaw and her mother was Bridget Stanley. Stanley was used as a middle name for two of John Charles’ children. Giles and Bridget had four other children, which included another John, who was to become a surgeon in the Attercliffe-cum-Darnall area of Sheffield.

- A pencil drawing of Sunderland by his pupil John Ness Dransfield shortly before Sunderland’s tragic death in 1855 aged 48. ~ Source Author

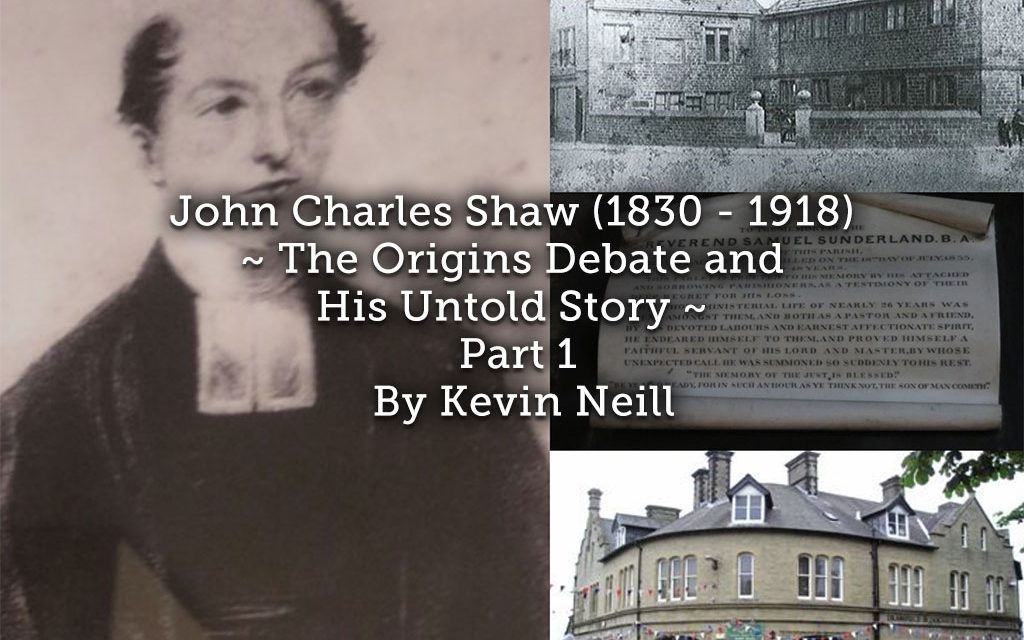

John Charles was born John Shaw. He was baptised John Shaw, at Penistone church, on 21st February 1830, by the Reverend Samuel Sunderland. The latter was to go onto become the Headmaster of the free Grammar School at Penistone. The middle name of Charles does not appear in any of John’s signatures until the 1850s. The 1841 census shows Benjamin and Elizabeth in Penistone, with son John. The 1851 census shows John Shaw – attorney’s clerk – a visitor at Pye-Bank[sic], Sheffield, to Mrs Jane Rennie. When John Shaw marries Mary Ann Garnett in 1853 at St Mary’s in Barnsley, he signs his name John Shaw, occupation, Clerk. In 1857, he is shown in The Post Office Directory of Yorkshire as John Charles Shaw, law stationer, 19 Norfolk Row, Sheffield. It is not difficult to assume that, shortly after his marriage, he adopted the middle name of Charles. There was a relation called Charles on his mother’s side. There are many similarities between John Charles Shaw and Charles William Alcock (of Football Association and F.A. Cup fame). The addition of a middle name to suit circumstances is one of them. It is hardly surprising that, with the plethora of John Shaw’s engaged in business in Sheffield at this time, this simple adjustment instantly raised him, in recognition, above the field and perhaps indicates something of an ambitious character.

John ‘Charles’ Shaw was raised in Penistone. He was educated at the Penistone Grammar School under the Headmastership of Samuel Sunderland. He did not attend Collegiate College in Sheffield, contrary to some sources. In 1906, John Charles Shaw writes a letter of application to join the Middle Temple in London, as a student of the bar. He is asked to give his educational background, as evidence for his acceptance and in his reply, John Charles clearly states that he was educated at Penistone. There is no mention of Collegiate College. This is significant to the claims that Collegiate College was a central tenet to the emergence of the modern game of soccer in Sheffield. If Collegiate College did not directly influence the footballing development of Shaw, which it clearly did not, it is essential, in this respect, to give consideration to Samuel Sunderland and Penistone Grammar School. John Goulstone, in his book Football’s Secret History talks of tracing soccer’s main ancestral line to an earlier time of 1840 around Penistone and surrounding area. This is well within Sunderland’s time and also builds on the work of Kevin Neill, Graham Curry and Eric Dunning in their recent article ‘Three men and two villages: the influence of footballers from rural South Yorkshire on the early development of the game in Sheffield’ (Soccer and Society 19, 1, 2018). The three men were John Charles Shaw, John Ness Dransfield and John Marsh.

The Reverend Sunderland is an interesting character. He was clearly well liked and loved by his parishioners, particularly John Ness Dransfield, who was in awe of him. Sunderland was born in Wakefield, in 1806, and educated at Queen Elizabeth Grammar School, where he attended from the age of ten. The school was situated on Brook Street, in the middle of town, close to the cathedral. There were no boarders. Outside space belonging to the school was limited. The Headmaster, at this time, was Martin Joseph Naylor. He had been born in nearby Batley Carr, but it is unclear where he went to school. He was however, admitted into Queen’s Cambridge in 1782, where he achieved third Wrangler (third highest score in the Mathematics Tripos) in 1784, became a Fellow in 1789 and graduated from B.A. in 1787 to Doctor of Divinity in 1829. He was appointed Headmaster at Wakefield in 1814 until 1837. Naylor was also Rector of Penistone and held the Living of the parish until his death in 1843. The Queen Elizabeth School was endowed to offer several scholarships and exhibitions to pupils. One, in particular, was the Cave Scholarship, offered to two poor boys of the school and parish to attend Clare Hall, Cambridge. Sunderland was the recipient of one of them. He obtained additional support through the Storie Exhibition, also offered by the school. Sunderland matriculated at Clare in 1825 and obtained Junior Optime (third class in mathematics) in 1829. His tutor was a John Evans, who had been to Shrewsbury School. Whilst there were other students at Clare from Shrewsbury, it was an eclectic mix of people from all over the country and from all educational backgrounds. Charterhouse school featured strongly, as did Rugby. Football was a part of boy culture within schools at this time.

- Sunderland’s memorial tablet in St John’s Church Penistone. Raised by subscription from his grateful parishioners. ~ Source Author

Sunderland’s experience of sport, whilst at school, is worthy of exploration, as this could well have had impact during his tenure at Penistone. Through Matthew Peacock’s work, History of the Free Grammar School of Queen Elizabeth Wakefield, we know that one activity enjoyed in schools by boys and, indeed, the masters, was cockfighting. The cock-penny was money paid to the master and usher to allow the sport to happen, and was used as a means to supplement income. In some schools, it was written into the statutes. Peacock is at pains to point out that he knew of no such practice at Wakefield. At Penistone during Sunderland’s time, there was a cock-pit at the back of the school wall on the Fairfields, approached down Cockpit Lane. Consideration also needs to be given to any football that Sunderland may have experienced, either at school or Cambridge. Peacock gives nothing away regarding this, but merely alludes to common practices nationally. Naylor’s usher, Reverend Joseph Lawson Sisson, attended Leeds Grammar School, as did Thomas Rogers, the previous Headmaster to Naylor. Further research may give some indication here as to the type and style of game played at Leeds. However, what remained a problem at Wakefield was the lack of space outside, together with the fact that the school catered for day boys and did not accommodate boarders. Any football ever played by Sunderland could have been limited, whilst at school. Cambridge, however, may well have been a different experience. A place where young men gathered, from across the country, grouped together in a single place with a varied experience of playing football. A melting pot of ideas wants and needs, particularly a desire to continue playing their game. Graham Curry in his thesis of Football: A Study in Diffusion suggests evidence that eight years after Sunderland left Cambridge, in or around 1837, an attempt was made to codify the various school rules, so that they could play football together. This is not to say that football of some sort was not played, in Sunderland’s time, and that he himself had been a participant. What is important is that Sunderland clearly encouraged his pupils to play sport, whilst he was at Penistone, which included football. Two of his former pupils, (John Charles Shaw and John Marsh) had a massive impact on the early Sheffield football scene, whilst a third (John Ness Dransfield), was described by Neill, Curry and Dunning as the ‘unsung catalyst’ of the footballing trio. Twelve years separated them regarding their birth, yet all three developed their footballing skills under Sunderland’s tenure as Headmaster at Penistone. The aforementioned Cave Scholarship allowed for seven years at Clare Hall. Sunderland was appointed as Curate to Penistone in 1829 after four years at Clare. Naylor was having difficulties with Penistone parishioners, who were unsettled with his continued absences. The fact that he reputedly had a wooden leg would not have facilitated travel easily. Securing Sunderland at Penistone to calm the storm clearly worked as he was popular and Naylor benefitted for the next fourteen years.

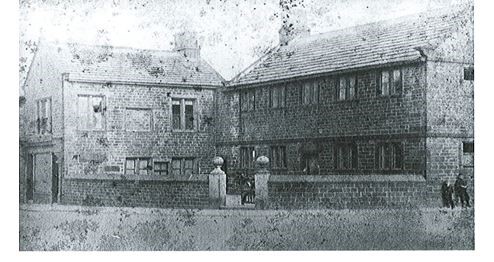

- Penistone Grammar School pictured before it’s demolition in 1893. ~ Source BBC News Sheffield & South Yorkshire 23rd June 2011

A contemporary of Sunderland’s at Cambridge was Thomas William Meller of Trinity Hall (1826-1830), a former pupil of Oakham, who was to become the first appointed Principal of Collegiate College Sheffield in 1836. They could well have been acquainted to one another, but this cannot be proved. Whether they had the same principles regarding student welfare, again, is unknown. Certainly from the writings of John Ness Dransfield, Sunderland had no objection to sport. Dransfield played football at Penistone as well as cricket. It could be argued that these activities were village related and nothing to do with the school or Sunderland. The evidence, however, points towards the time of Sunderland’s arrival. There was a fundamental difference between Sheffield Collegiate College and Penistone Grammar School, namely the environment. Collegiate College was urban and enclosed; Penistone was rural, with a walled school yard and open fields beyond. These fields could be accessed by day boys of the school and local youths. Both schools had boarders, though Penistone was on a much smaller scale than Collegiate. Meller could entrust his charges were safe behind the walls of the establishment, while Sunderland, on the other hand, had to ensure that his boarders were within easy reach of his care, namely the school house and the fields that lay just outside. The school was built on what was called the Kirk Flatt and the surrounding land was known as the Fair Fields. It was in the Fair Fields, before the advent of the railway, where football had been played. It was rough ground cut with a scythe, rather than machine and towards the north side was sloping ground, dropping steeply down to the River Don. To the south were buildings, cottages with outhouses containing materials easily damaged by misguided footballs. To the east was the school and to the west gently sloping ground. Football, in its various forms, can be said to have been shaped by the interaction of players with the local environment. Charterhouse and the Cloisters, Rugby and the flat extensive fields and Harrow with the cloying clay soil making for a very heavy ball. The type of football played in Penistone was primarily a dribbling game and it involved minimal handling. But the handling it contained was a causal effect of the land. Rough ground for instance could dramatically alter the dribble and cause the ball to bobble and bounce. A document outlining land owned by the school and trustees mentions the ‘roughe field and rough field inge in Penistone in the schoolmasters occupation’.

- Sheffield Union Banking Company building on the old school site. The architects sympathetic to the original school entrance. ~ Source Author

By knocking the ball on with the hand, when a bounce happened, the dribble was allowed to continue in best fashion. Similarly, when the ball was kicked, a fair catch enabled the dribble to continue again and stopped the ball from running away into the River Don, being lost or from breaking windows or damaging property both to the south and west. The game also determined that the ball was kicked below a certain height to offset similar problems, namely in scoring a goal. There were no written rules to determine the order, nor was there an established club, as neither of these was necessary to facilitate play. If it had been introduced by Sunderland based on his experiences at Cambridge, then it was a perfect fit. It would have reinforced what was a long standing tradition of that type of football in the area.

Article © Kevin Neill

To read Part 2 see – bit.ly/2Zgd874, Part 3 – bit.ly/2ZdrvZV and Part 4 – bit.ly/2WXDYUe

![The Case of Italy v England [1976], Which Was Not Broadcast Live on Italian TV to Fight Workplace Absenteeism](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/PP-banner-maker-6-440x264.jpg)