Playing Past is delighted to be publishing on Open Access – Sporting Lives, [ISBN 978-1-905476-62-6] a collection of papers on the lives of men and women connected with the sporting world. This edited volume has its origins in a Sporting Lives symposium hosted by Manchester Metropolitan University’s Institute for Performance Research in December 2010.

Please cite this article as:

Oldfield, S. J. George Martin, ‘Wizard of Pedestrianism’ and Manchester’s Sporting Entrepreneur, In Day, D. (ed), Sporting Lives (Manchester: MMU Sport and Leisure History, 2010), 142-166.

10

______________________________________________________________

George Martin, ‘Wizard of Pedestrianism’ and Manchester’s Sporting Entrepreneur

Samantha-Jayne Oldfield

______________________________________________________________

The public house during the nineteenth century was at the heart of the Victorian community; flower shows, fruit and vegetable shows, glee clubs, amateur and professional dramatics, bowling, quoits, pugilism, foot-racing, and society meetings were provided within their grounds.[1] Although appearing to help rationalise recreation time, the innkeepers were ‘fully aware of the profit-making potential of such an enterprise’, and pioneering publicans used entertainments to attract audiences with some establishments forming allegiances with specific ventures in order to gain higher proceeds.[2] Sport essentially became property of the drinks trade and it was these entrepreneurial landlords who were fundamental to the survival of sport in industrial cities, however, ‘sufficient credit has never been given to the nineteenth century managers and professional running grounds for laying the foundations of the modern athletic meet’, a topic in need of further exploration.[3] This paper provides a biographical study of one of these individuals, the innovative George Martin (1827-1865), one of Manchester’s athletic sporting entrepreneurs.

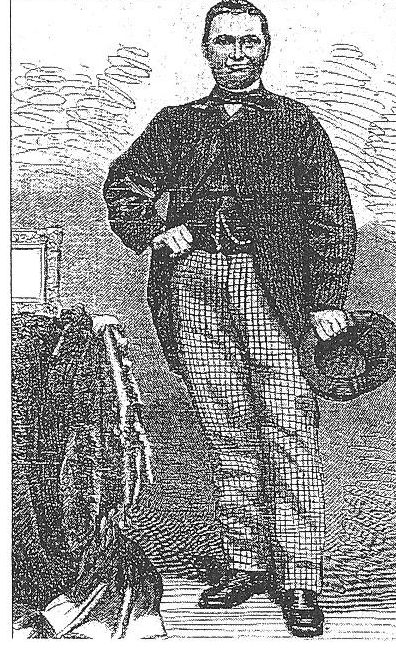

Figure 1. George Martin

© Deserts Island Books

George Martin was born in 1826 in Blackwater, Hampshire, son of Prudence and James Martin, a local shoemaker.[4] From a working class background, Martin entered into the family trade in his adolescence, a common practice in nineteenth century Britain; entrusting kin with skills for employment, or providing funds to apprentice them in an appropriate trade was imperative to the father-son relationship as this provided independence and status for the family, and ‘property in skill’ which secured the future.[5] Residing with his grandparents, John and Martha Yeoman, in Frimley, Surrey, by 1841 Martin was practising as a journeyman shoemaker.[6] However, at the age of 18, Martin turned to sport for his fortune and moved to London to pursue a career in pedestrianism under the care of 28-year-old Edward “Ned” Smith, the ‘West-End Runner’.[7] Throughout his career he continued to practise as a shoemaker and boot closer, which affected his attendance at some events, causing him to forfeit matches, and led to insolvency claims.[8]

Martin followed traditional practices, as illustrated in The Training Instructor;

…as soon as a man determines to go into training, it is, of course, advisable that he go into training quarters. These, if they can be obtained in another town to that in which he lives, will be all the better from the fact that they are situated some distance from the pedestrian’s old haunts…and if he lodged in a public house it would not matter. [9]

He resided at the White Hart, Drury Lane, with mine host, Ned Smith, and proprietor, John “the Regent Street Pet” Smith, who provided facilities for several athletes.[10] Both men were well established peds, ‘celebrated trainers’, and athletic backers, Ned a hurdling champion and John a sprinter, originally trained by brother, Ned, with his preferred distance being a quarter of a mile.[11] The Smith brothers used their expertise to train novices and create first-rate pedestrians; the most successful graduates being Patterson, alias ‘Pet’, ‘Blower Brown’, Spooner, and Martin himself, nom de plume being ‘Ned Smith’s Novice’.[12]

Pedestrianism, or foot-racing, provided the majority of entertainment during the mid-century, a well-established amusement in which large numbers of people took part.[13] Sprinting (from 110 to 880 yards) and the “Miler” were the events of choice for most athletes and spectators alike, due to their fast paced nature, although, by the 1840s, hurdling also became as popular, with men jumping over obstacles of all shapes and sizes.[14] Such events attracted large crowds, regularly in their thousands, with the publican reaping the rewards through drink proceeds, betting commission, and eventually gate fees when these ground became ‘enclosed for a specific sporting purpose’.[15]

At 8st 6lb Martin was conditioned as a 120 yard sprinter and short distance hurdler, making his first appearance in 1845, at the age of 18.[16] After a successful start to his athletic career, support and admiration for Martin was apparent, resulting in backer, Smith, to challenge any young pedestrian in England to beat his man, which was quickly accepted by Birmingham based ped Joseph Messenger, and provided Martin with his first race outside the metropolis.[17] The competition was reported in Bell’s Life, detailing the expense to which the grounds proprietor, Mrs Emerson, had gone to accommodate both youths, and although Martin lost he was highly praised, with reports stating ‘two smarter fellows could not be picked in England, but Martin looked in the best condition, although he had but a week’s training’.[18] On his return to London, Martin appeared in hurdling events at the Beehive Cricket Ground, Walworth, where his previous failures were eclipsed by his successes with prizes which included a silver snuff-box, a silver watch, and a silver cup for a ‘300 yards, and to leap 15 hurdles’ event.[19] Again, Martin and his trainer were praised, with reports stating ‘the pedestrian school that he [Martin] was brought up in must be a first-rate one, in producing so good a runner, who will, no doubt, with care, prove something extraordinary’.[20]

Towards the end of 1846, Martin was unbeatable and started to gain negative press for illegally entering competitions.[21] Soon afterwards, Martin filed for bankruptcy and was remanded for two months and, after a quiet year, moved out of London only to re-emerge in the pedestrian community as ‘George Martin of Sunderland’ in 1848.[22] Residing at ‘sporting victualler’ Mr Harrison’s, Golden Lion, Sunderland, Martin challenged men in the North East to sprinting and hurdling events, many of which he won with ease.[23] Not content with human competition, Martin tested his talent against horses and his events became the main attraction at Sunderland’s running grounds luring spectators in their thousands, although betting was minimal.[24] However, his previous reputation had followed him and it was not long before controversy surrounded the ped, with many supporters of the sport concerned about Martin’s hoaxing of the public, with Bell’s Life announcing, ‘Martin frequently offers to make matches, but as frequently disappoints parties. Let us have a little more work, and not so much talk’.[25] Nonetheless he continued to race as many spectators, and sporting papers, still supported the infamous hurdler and his indiscretions became secondary to his skill. This was not the first and last time Martin’s reputation was threatened as towards the end of his career allegations of match-fixing, violence and fraud were widely reported; a common component of professional foot-racing, especially towards the 1860s and 1870s.[26]

In 1849, Martin, a ‘pedestrian of celebrity’, ventured towards Manchester where he trained and conditioned himself for athletic competition. His physique was marvelled, ‘being well built about the chest and thighs, with a waist as fine as a lady’, and his dominance in the sprinting world was greatly admired.[27] Regularly spotted at the White Lion, Long Millgate, Martin formed a friendship with James Holden, the ‘great stakeholder of Lancashire pedestrianism’ and proprietor of aforesaid public house.[28] Holden’s inn was well renowned for holding monies for most of Manchester’s events ranging from the average pedestrian feat, rabbit course and quoits fixture to the more obscure bell ringing challenges, and the 1846 ‘match for a Yorkshireman to fight a main of cocks’.[29] Stakes, deposits and articles of agreement were regularly produced and held at the White Lion, and professional athletes would use this establishment as a meeting place where contests could be arranged, financed and promoted.[30] Bell’s Life and The Era would regularly print Holden’s name and public house within their pedestrian sections showcasing their gratitude for the ‘respectable stakeholder, James Holden’.[31]

A small group of pedestrians which included Martin, Henry Reed of London, Edward “Welshman/Ruthin Stag” Roberts, Henry Molyneux of Halifax, John “Regent Street Pet” Smith, Charles Westhall, and George “the American Wonder” Seward, regularly competed against each other in hurdling and sprinting events at different venues throughout England.[32] In July 1849, Seward recognised the potential for an exhibition demonstrating athletic prowess and the “Seward Benefit”, which saw himself and Reed ‘tour through the towns that he has visited’ throughout his time in England, was established in July 1849.[33] 5ft 7, 11st American, Seward, was born in Newhaven, Connecticut on 16 October, 1817, beginning a triumphant athletic career in October 1840. In 1843 he travelled to England searching for new athletic competition, working and living in Durham, and befriending Martin in the process. British pedestrians ‘succumbed to his truly astonishing powers’ and he was named ‘Champion of England and America’, although the term “Champion” was rather ‘loosely employed’ and given to athletes by pedestrian promoters as a means of generating public patronage.[34] Nonetheless, his pedestrian feats attracted thousands of spectators, but by 1849 his audience had dwindled. The American secured funding for a ‘monster pavilion (capable of holding 10,000 persons)’ which was to travel around the United Kingdom performing ‘old English sports and pastimes…which many “first-raters” have entered’, one of which was 22-year-old Martin. This short-lived amusement, aptly named ‘The Great American Arena’, was to commence at Peel Park Tavern, Pendleton, on 24 September, 1849, but was postponed until 1 October since the canvas could not be constructed in time.[35] On its grand opening, in the presence of approximately 2,000 people, George Martin defeated Roberts, Flockton and Smith in a 300 yard hurdle race to win a silver snuffbox before Seward conquered “Black Bess”, Mr Harwood’s mare, in a 100 yard event.[36] The circus soon ended when it became impossible to dismantle, transport, and erect the tent effectively, with the final performance being held in Rochdale on October 8, 1849.[37]

Martin, for many, was a pedestrian sensation, his ‘condition, style, and manner, became the theme of admiration’, and, although short in stature;

Martin’s skin was clear, step elastic, eye…bright as a diamond, and as full of confidence as man could possibly be…Martin is as smart a pedestrian as can be met…and, when he chooses, can run both beautifully and excellently, in fact he is a little model.[38]

Martin’s association with the Holden family, and his growing relationship with daughter Alice Holden, encouraged the ped to frequent Manchester more regularly and eventually led to his relocation to the city in 1851.[39] On January 14, 1851, ‘the smart and dapper George Martin…led the good tempered Miss Alice Holden, eldest daughter of the great pedestrian banker, to the alter’, at St John’s Church, Manchester, and two month later took proprietorship of the Plasterer’s Arms, 29 Gregson Street, Deansgate, Manchester.[40] The role of licensed victualler became a popular business venture for many professional sportsmen; in London in the 1840s, prizefighter Young Dutch Sam gave lessons at The Black Lion, which was ‘patronized by the friends of boxing and athletic sports in general’ while Frank Redmond, at The Swiss Cottage, entertained all the ‘celebrated pedestrians’.[41] Professional swimmer Frederick Beckwith was, variously, landlord of The Leander, The Good Intent and The Kings Head, all in Lambeth, between 1850 and 1877, while The Feathers in Wandsworth, run by rower John H. Clasper, was popular with both scullers and swimmers.[42] Outside of London, peds owned and frequented specific pubs. In 1855, pedestrian trainer James Greaves took over the Ring of Bells where anyone attending foot races in Sheffield area would ‘meet with every accommodation’.[43] The professional mile record, set in a dead-heat at Manchester in August 1865, was established by William “Crowcatcher” Lang, host of the Navigation Inn, Ancoats Street, Manchester, and William “The Welshman” Richards, landlord of the White Horse, Tollawain.[44]

Through their social functions, pubs had a long and important history in shaping loyalties to locality. They were places where fields were provided, sport sponsored, pedestrian challenges agreed, bets were laid and teams changed. Frequenters of “sporting houses” often had their own allegiances, and lent general support to a particular, rower, pugilist or pedestrian before a match.[45]

Martin continued the trade of father-in-law James Holden, and his pub became a pedestrian base where stakes and deposits could be paid. His old sporting friends lodged at his hostelry and he continued to race himself within the Manchester area.[46] Due to his expertise in the sport, Martin also became a trainer for many young sprinting peds; a preferred distance for many as training was not laborious.[47] His protégés included William Neil of Stockport, his old rival Edward “Ruthin Stag” Roberts, and an amateur Grenadier Guard, Sergeant Newton.[48] Martin regularly requested matches for himself and his athletes in the pages of Bell’s Life, as well as informing the athletic community of his booths where pedestrians could view his athletes before entering into articles of agreement.[49] His travelling huts, ‘25 yards by 10, and canvas top. The fittings consist of a counter, seats, spirit kegs, pots, &c.’, provided alcohol at race meetings in and around Manchester, where, besides flat-racing, pedestrian, gymnastics and horse riding events were showcased; a demonstration of Martin’s early entrepreneurial vision.[50] The sporting publican as early as the 1840s extensively endorsed pedestrian races, and the sport ‘which had its own heading in Bell’s Life in 1838’, gained popularity, peaking in the 1860s, by which time the organisation of amateur sport by middle class society lead to a decline in professional activities.[51]

In 1852, Martin’s family expanded with the arrival of son James, his first of six children, and soon afterwards Martin left The Plasterer’s Arms, transferring the license to ex-professional rower, and brother-in-law, George Piers in 1853, and returned to London with his family and athletes, and resurrected his shoemaking business in the capital.[52] Ex-professional rower, and brother-in-law, Piers, patron of the Manchester Arms, Long Millgate, married Sarah Holden at Manchester Cathedral in 1852.[53] Traditionally a printer, Piers had been inaugurated into the pedestrian faction through his wife Sarah, who was apprenticed in the drinks trade by her father, James Holden.[54] In Holden’s absence, Piers would often be present as starter, referee and timekeeper for local athletic and shooting events, eventually acquiring The Royal Hunt, Bury Street, Salford, where he became involved in rabbit coursing.[55]

Suffering from mental illness and unable to cope, Martin’s father, James, in 1854, murdered wife Prudence and then committed suicide at their home at Clarence Gardens, St Pancras.[56] As the eldest son, Martin returned to the capital to organise funeral arrangements, comfort his siblings and to manage the family shoe-making business.[57] He continued to be active within the pedestrian community by coaching army athletes and training professional pedestrians whilst competing locally and arranging events from his new residence at 7 Little Windmill Street, Golden Square, Westminster.[58]

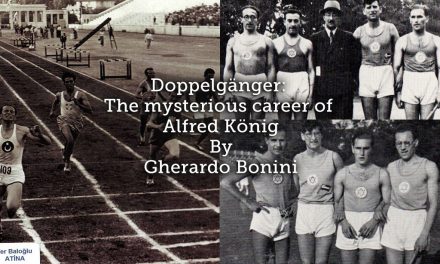

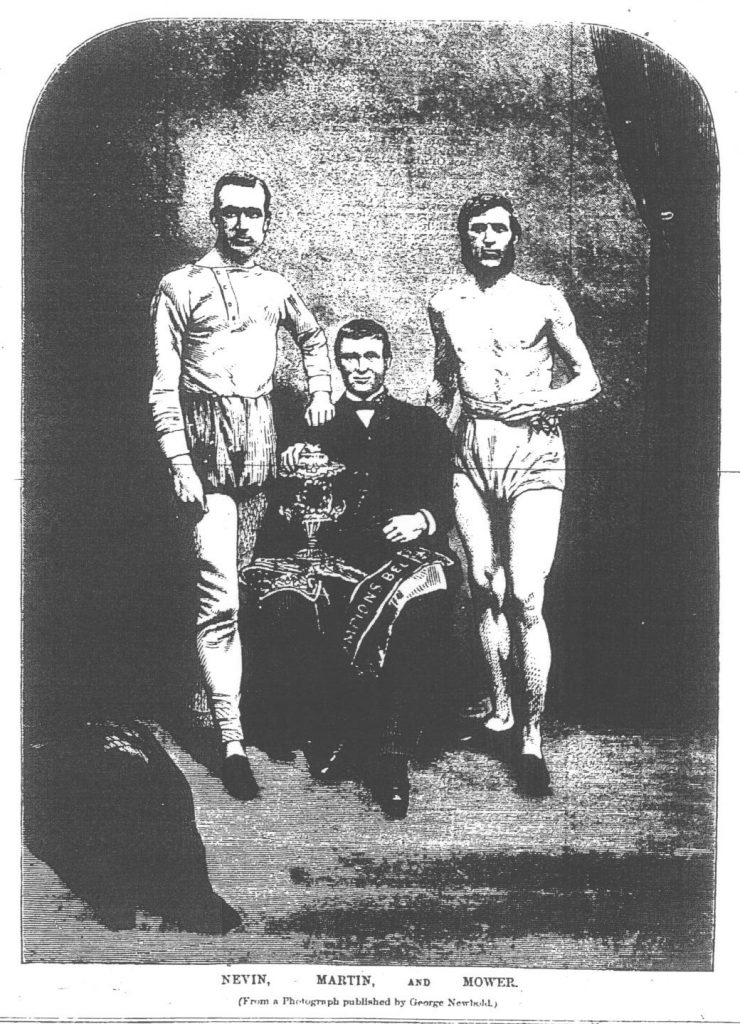

In May 1858, Martin again filed for bankruptcy and soon after, at the age of 30, he announced his retirement from the sport of pedestrianism stating that he wished to pursue training full-time, housing athletes in his home at 14 Walter Street, Regent Road, Salford, which was within close proximity of the well-established Salford Borough Gardens, Regent Road, Salford, proprietor Mrs Ann Attenbury.[59] His training pedigree and “celebrity status” meant Martin ‘was the star round which the Manchester men concentrated’, and his athletes, Charles Mower, John Nevin and John White, who resided with Martin and his family, were strictly trained and promoted, becoming champions within the sport.[60]

In May 1861, Martin, as part of his promotion of the aforenamed pedestrians, sailed to America with the intention defeating his American counterparts.[61] On their arrival to the USA, the athletes entered competitions at the Fashion Race Course, Long Island, where their talent could not be matched and they remained undefeated. On 10 July, 1861, White and Mower competed in ‘the great ten-mile foot-race’ against two Cattaraugus Indian athletes, Bennett and Smith, who, according to the New York Daily Tribune, ‘walked around with the imperturbable gravity of their race, and evidently viewed their two white competitors with complacency’.[62] 28-year-old native, Louis “Deerfoot” Bennett, who at 5ft 11½ and 11st 6lb overshadowed the British athletes, led the race from the start.[63] However, at the seventh mile, White, who had been ‘running as light as an antelope’, overtook the exhausted Bennett and claimed victory to ‘the enthusiastic applause of the spectators’ where Martin’s techniques were congratulated, with reports stating White’s focus and execution had ‘certainly never been seen in this country’.[64]

Although elated with his runner’s success, Martin was impressed with Bennett, and encouraged the Indian to travel to Britain.[65] In July 1861, the Indian raced in costume around the decks of the Great Eastern and, on his arrival to Britain, began training under the watchful eye of Jack MacDonald, a solicitor, amateur runner and ‘advisor’ to Cambridge University athletes, ‘who has been appointed by his [Bennett’s] American backer to look after his interests’. [66]

Figure 2. John Nevin, George Martin and Charles Mower with Champion’s Belt and Championship Cup

Illustrated Sporting News and Theatrical and Musical Review, March 29, 1862, 17

(c) British Library Board (Mic.A.2580-2585)

Many sporting men had come to view the ‘Red Jacket’, as illustrated below;

We do not remember to have seen for a long time past such an array of vehicles arriving at these grounds, and within the enclosure between 2,000 and 3,000 spectators were assembled, including many gentlemen who are not frequently in the habit of visiting courses set apart for foot racing. In short, all grades were present, including officers belonging and not belonging to the police; pedestrians (including the champion); pugilists, represented by the ex-champion; wrestlers of considerable note; the bar was represented by the presence of a barrister instead of a felon; the Turf by several connected with it, not omitting pigeon-shooters, as well as a considerable number of “publicans and sinners”.[67]

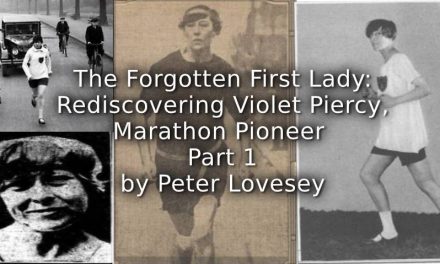

A ‘marketing genius ahead of his time’, Martin, aware of the interest surrounding Deerfoot with both the sporting and British public and press, approached Bennett after his “ten-mile champion” success, and proposed a tour of the athlete around the United Kingdom.[68] Martin planned and financed the show, entitled the “Deerfoot Circus” which, by the same principle of Seward’s 1849 arena, would see Bennett and several professional athletes compete in sporting feats as part of a travelling exhibition. The tour was arranged and Deerfoot plus various famed pedestrians including ‘six-mile champion’ Teddy “Young England” Mills, ‘four-mile champion’ John “Milkboy” Brighton, ‘mile champion’ William “Crowcatcher” Lang, and ‘English champions’ Mower, William “American Deer” Jackson, Stapleton and Andrews, agreed to compete every day, except Sunday, in four-mile displays whilst other athletes; pedestrians, jumpers, boxers, and horsemen; partook in ‘all kinds of old English sports’.[69]

Whilst the circus was being constructed, Martin continued to promote Bennett. As ten-mile Champion, the Indian was required to race any man who wished to challenge his title, and Martin announced these events within the pages of Bell’s Life.[70] Deerfoot’s limits were challenged and he was subjected to many sporting trials, with the conclusion that distance running was his forte.[71] However, not satisfied with his pedestrian dominance, Bennett challenged ‘champion swimmer of England’, Frederick Beckwith, ‘to swim 20 lengths of Lambeth Baths, for £50’, but this was ultimately forfeited one week before its execution due to the Red Jacket’s demanding schedule.[72]

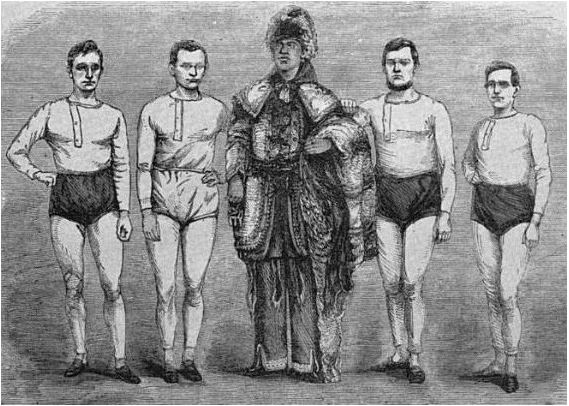

Figure 3.Celebrated peds

Left to right, Edward “Teddy, Young England” Mills, John “The Milkboy” Brighton, Louis “Deerfoot” Bennett

William “Crowcatcher” Lang, and Samuel Barker of Billingsgate

Illustrated Sporting News and Theatrical and Musical Review, May 10, 1862, 38

(c) British Library Board (Mic.A.2580-2585)

In December 1861, Martin travelled to Cambridge University where, in the presence of the Prince of Wales, he watched Deerfoot overcome Lang, Brighton and Barker in a six-mile contest.[73] Doubts about the legitimacy of these events had started to surface; The Racing Post suggested, ‘the pedestrians whom Deerfoot has “beaten” have been hired to play their part in the farce like any other actor’, this view being confirmed when Edwin “Young England” Mills reported that his non-start at the Cambridge race was due to his reluctance to ‘play second fiddle to the red ‘un…the consequence being that they [Martin and MacDonald] would not allow him to start at all’.[74] Nonetheless, visitors of both sexes still travelled, and paid, to see the ‘star runner’ which Martin used to his advantage.[75]

Martin was known as the ‘wizard of pedestrianism’ or the ‘wizard of the North’, according to Sears, ‘for his innovative ideas and promotional abilities’, examples of which are clearly demonstrated through Deerfoot’s competitions.[76] Martin had stakes in photographs of the Indian which were hung in public houses all over Britain, lithographs produced in Illustrated Sporting News and Theatrical and Musical Review, and the operetta “Deerfoot”, which became a musical hit.[77] As part of the racing “show”, Martin would parade Bennett in native clothing with ‘wolfskin cloak’, ‘buckskin moccasins’ and around his head ‘one eagle-feather, the symbol of victory and power’, his racing apparel being ‘tights, and wearing a girdle richly ornamented with floss silk and feathers, and also a slight belt, to which several small bells were attached’.[78] Deerfoot would present his war-cry, a ‘yell so shrill, ear-splitting, and protracted’ when he defeated his opponents and, as Hayes describes;

…when Martin thought he [Deerfoot] had exercised his legs enough, he used to run into the middle of the course, stretch out his arms, shout out some gibberish, which passed for Cherokee or Iroquois, and try to stop the wild man who used to act the part to perfection and take a lot of catching and holding.[79]

The performance element of the races added to their entertainment value and when the ‘Deerfoot Travelling Race Course’ opened in May 1862, Martin continued to present the native in a similar manner.

G Martin wishes to inform the public that, having received so many application for Deerfoot to run at various parts of the country, and so few places being enclosed where a race can take place, Martin has, at an enormous expense, built a travelling race course, twelve feet high, and nearly a quarter of a mile in circumference, so that a race can take place in any town where an even piece of ground can be selected.[80

‘Mr Martin’s monstre canvas race course, 1,000ft in circumference’ contained a 220 yard portable track for these demonstrations, which was transported by road to each venue, whilst the athletes themselves travelled by rail. The tour regularly attracted 4,000-5,000 spectators from all backgrounds, including ‘a large proportion of ladies, noblemen, any officers, and a great number of military’.[81] The races started each evening at six, with admission from five for the prices of 1s within the amphitheatre and 6d in stand, where there were also ‘seats for ladies’.[82] However, as the weeks continued Martin began to struggle financially and trouble with the law ensued.

‘Tales emerged of heavy drinking and the occasional brawl, and as the weeks went by the reputation of Martin and Deerfoot, in particular, took a pounding’.[83] Martin was prosecuted for assault and ordered to face one month’s imprisonment or pay a £3 fine, the latter being chosen, with Bennett also being charged for strangling a spectator.[84] Within the crowds, pick-pocketing occurred which led to confrontations in court, and members of the “circus” staff were tried for robbery.[85] Martin’s athletes, being concerned with the growing number of illegalities, presented as witnesses against their manager, and on the 23 October 1862, William “American Deer” Jackson, with the support of his fellow performers, effectively sued Martin for lack of pay and poor living conditions. Throughout the hearing, and in the presence of numerous reporters, Jackson announced that the matches were fixed with Martin ‘working’ them in the Indian’s favour and, as a result, interest in the extravaganza subsided, concluding on 10 September 1862, only five months after its launch.[86] Due to the negative attention surrounding Deerfoot, in May 1863, the Indian returned to America with ‘upwards of a thousand pounds as the fruits of his running labours’, becoming the wealthiest man in his reserve.[87] Deerfoot always maintained that his races were legitimate and, before his death in 1896, he insisted that his training was the same, if not more intense, than all of Martin’s athletes, he ‘ran and walked at least forty miles a day…his trainer watched with a watch in one hand and a whip in the other…he had no rest…only at night’.[88]

Martin’s reputation was severely damaged with news reports emerging which discussed his ‘dishonourable character’ and ‘disgraceful shams and frauds upon the public’, with County Court Judge, Mr J.F. Fraser, announcing ‘I trust that you (addressing the reporters) will convey my strong opinion of such disgraceful affairs’.[89] Still, Martin continued to work as a trainer and backer at his new home in Garratt Lane, Tooting, near to Mr John Garratt’s ‘Copenhagen Grounds, Garratt-Lane, Wandsworth’, where he constructed, witnessed and held articles of agreements for races against his pedestrian athletes.[90] Undefeated, in November 1863, Martin returned to Manchester where he undertook a new business project which contributed to his “celebrity” which was maintained for years to come.

Table 1. The “Deerfoot Circus” Schedule 1862[91]

In the mid-1860s, pedestrianism started to decline, and ‘this triple role of promoters, layers, and backers…could only have one conclusion, namely, the loss of confidence from the public and the ultimate collapse of the whole series of promotions’.[92] However, Martin, not deterred by the failure of his previous endeavours, retired as a trainer and backer of pedestrians and announced his intention to develop the grounds attached to the Royal Oak Hotel, his new establishment on Oldham Road, Newton Heath.[93] Location was perfect; Miles Platting railway station was nearby, omnibuses and trams stopped within 200 yards of the ground, and it was less that half a mile from the renowned Copenhagen Running Grounds attached to the Shears Hotel, proprietor Thomas Hayes, with whom Martin had prior connections. Sixteen-acres of land were enclosed, with Martin spending £2000, approximately £145, 000 by today’s monetary value, to ensure the ground would be ‘first class’.[94]

In February 1864, Martin advertised his grounds within the pages of Bell’s Life, informing the public of its imminent opening.[95] The ground boasted and 651 yard circular track, quarter of a mile straight course, circular 750 yard rabbit course, wrestling arena, bowling green, quoits ground, trotting course and grandstand, all within the fenced enclosure capable of holding 20,000 people with ease. Further amenities included a shower-bath with soap, towels and brushes which could be used by the public for the sum of one penny, and a portable dressing room, with carpets and fitting, where athletes could ‘strip by the fireside opposite the starting post’.[96] Reports in the Manchester Guardian claimed Martin had created ‘one of the most superior sporting arenas in England, if not the world’, with the Illustrated Sporting News and Theatrical and Musical Review insisting that Martin was ‘the right man at the right place…we trust Mr Martin will receive that support which he deserves’.[97]

The ground officially reopened on the 17 April, 1864, to crowds of over 3,000 spectators, with the first event, comprehensively promoted within the sporting press, being the ‘great mile race for £25 a side’ between ‘celebrated “clippers”’ Siah Albison and James “Treacle” Sanderson.[98] In conclusion of the athletic events music played which ‘greatly enlivened the proceedings’ and the Era reported that the Royal Oak would, ‘no doubt be the finest enclosed pedestrian ground in the kingdom’.[99] With the Copenhagen Grounds being within the locality of the Royal Oak, Martin and Hayes, as proprietors of the attached public houses, worked in conjunction with each other to ensure profits. Spectators migrated from stadium to stadium and their sporting entertainments became day-long affairs.[100]

Martin followed the same principles as previous successful publicans such as William Sharples, proprietor of The Star Inn, Bolton, who provided a concert hall with dancing, acrobats, clowns, waxworks, live exhibits and ornamental gardens, regularly filling to its 1,500 capacity, and the famed Mr Rouse, of the Eagle Tavern, City-Road, London, who provide entertainments such as the T.Cooke’s Circus, “Cockney Sportsmen”, and grand concerts within the Grecian Saloon and Olympic Temple, ‘capable of containing about fifteen hundred people’, as well as ‘ornamental pleasure grounds…most tastefully laid out in parterres of flowers and gravelled walks, relieved by beautiful fountains’.[101] Martin’s grounds featured ornamental gardens with statues and sculptures, pianists and singers, aeronauts and photographers, as well as “live exhibits”, such as Tonawanda Indian, “Steeprock”, who resided in a wigwam in the centre of his newly constructed arena, and in September 1865, the Gypsy King, Queen and tribes who were displayed in a similar fashion.[102]

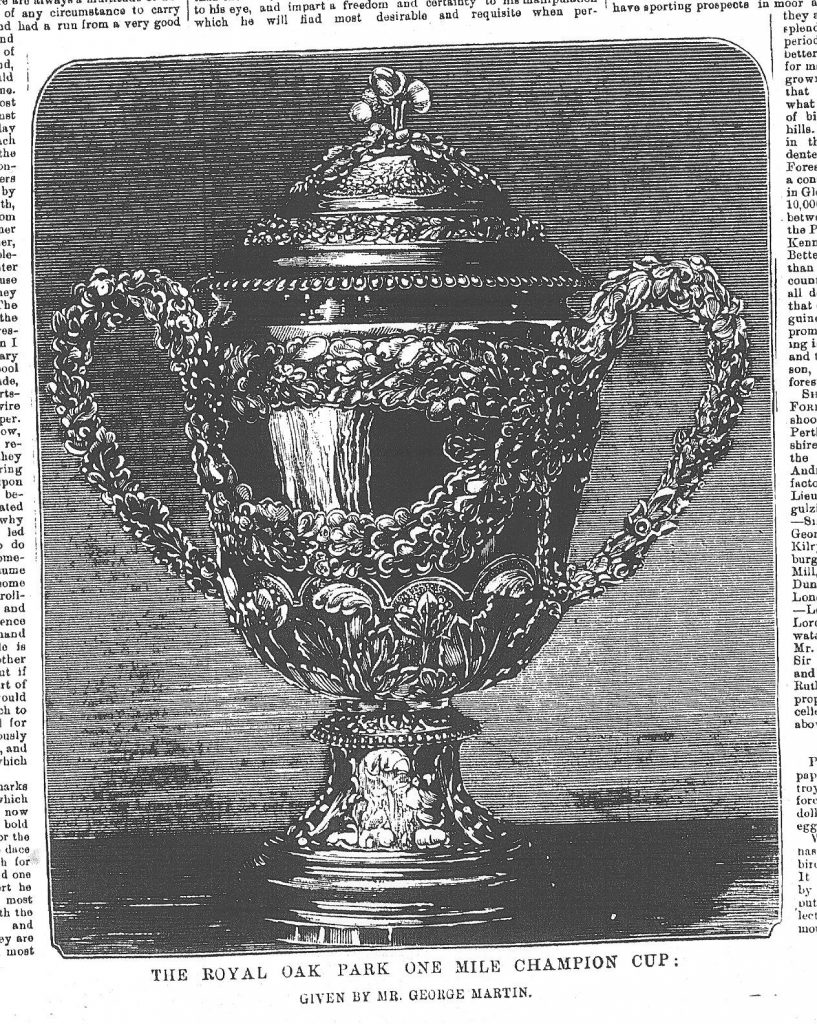

Martin wanted to provide the pedestrian society with a truly magnificent spectacle and through his promotional skills, he publicised the first annual competition for the ‘Great Mile Championship’, a contest which continued in his memory after his death. Six champion “clippers” were invited to compete for ‘a silver cup weighing 76oz (which immediately becomes his absolute property), in addition to £110 in money’, those athletes being Mills, Sanderson, Lang, Nuttall, Stapleton and Albison.[103]

Figure 4

‘Royal Oak Park One Mile Champion Cup’

Illustrated Sporting News and Theatrical and Musical Review, August 5, 1865, 344

(c) British Library Board (Mic.A.2580-2585)

The first competition was held on the 25 June 1864, in the presence of over 20,000 spectators where, according to the Sheffield & Rotherham Independent, ‘all the London Deerfoot exhibitions…were completely cast into the shade’. Entrance fees equated over £600, and the ‘rush for admission was so great that the gates were burst through, and thousands gained admission for free’. Martin took the role of starter and referee and introduced the athletes to the crowds, who paraded around the arena in their colours before being numbered and placed into their starting positions. The race was fast, with the winner, Edward “Teddy” Mills, completing the mile in four minutes twenty seconds, to the thunderous applause of the audience.[104] The following year, on the 19 August 1865, the second instalment of the ‘One Mile Champion’ was organised, this time for twelve months claim to a ‘magnificent gold cup’ plus ‘one half of the admission money taken at the gates’, where, once more, Martin took position as starter and referee.[105] Upwards of 15,000 people witnessed the race between Mills, Sanderson, Lang, Stapleton, Neary, Mower, Richards, Albison, McKinstray and Nuttall, which resulted a dead-heat between William “Crowcatcher” Lang and William “the Welshman” Richards, ‘time four minutes seventeen and a quarter seconds – the quickest time on record’.[106]

Although the grounds were in excellent condition, Martin was not; his physique, which had previously been praised, had become rotund and he looked older than his father-in-law Holden, who was nearly 30 years his senior.[107] In September 1865, reports spread that Martin, ‘the energetic and spirited proprietor’, had been suffering from ‘mental afflictions’ and was unable to officiate in his ‘present state’.[108] And on the 7 September 1865, Martin was hospitalised at Wye House, a private asylum, ‘for the care and treatment of the insane of the higher and middle classes’, for ‘over attention to business and excitement’.[109]

The Victorian asylum was viewed negatively, as were the lunatics themselves. According to Cambridge County Council, the 1845 Lunacy Act and County Asylum Act ‘fundamentally changed the treatment of mentally ill people from that of prisoners to patients…one of the great moves towards compassionate social reform’.[110] The Acts were concerned with the lack of “pauper” asylums; county ran institutions, hospitals, workhouses and prisons; which had a long history of mistreatment of inmates and overcrowding.[111] During the nineteenth century ‘charitable hospitals’ opened which provided the upper and middle class lunatics, for a fee, refuge from the county asylums, and it was common for these private asylums to be discussed as “retreats” where families could commit ‘disturbed relatives’ for a period of respite.[112] Ultimately, these private institutes were expensive and if patients could not afford their hospitalisation they would be admitted into state-funded establishments.[113]

Figure 5

Wye House Asylum, Buxton

‘for the care and treatment of the insane of the higher and middle classes’

Post Office, Post Office Directory of the Counties of Derby, Leicester, Rutland and Nottingham (London: Kelly & Co. 1876), 36.

Wife, Alice, committed Martin for his continued rambling and refusing to sleep. Friend, and ex-athlete, Teddy Mills stated ‘he refuses food; and also refuses to see his wife saying that she wants to kill him’, with John Parke insisting, ‘he declares he is going to make his racing grounds into a paradise and invite the French King, Victoria and all the Royal Family. He is going to lay the Atlantic Cable and have it completed in a month and he is going to invite the moon down into his gardens and make £100,000 a month’, and acute mania was certified.[114] However, less than a week after his admission Martin was discharged, said to have ‘recovered by the authority of Alice Martin’.[115]

On the 21 October, 1865, 38-year-old Martin died at St Martins Workhouse Hospital, Middlesex, cause of death being ‘cerebral disease’ due to mania.[116] His death at such a young age shocked the sporting community and there was concern that the grounds would never be the same again.[117] The following obituary was presented in the pages of Bell’s Life on 28 October 1865, the publication which for so many years had supported the notorious entrepreneur;

We regret to announce the death of Mr G. Martin, the enterprising proprietor of the above extensive sporting area, which sad event took place as St Martin’s, London, at half-past two a.m., Oct 21. For several years he was well known as a professional pedestrian, and his name is familiar throughout the three kingdoms as the party who introduced Lewis Bennett (alias Deerfoot) to these shores, with what success our readers are well acquainted. In the estimation of the late George Martin all other sports sunk into comparative insignificance when place in juxtaposition with pedestrianism, and his last effort in that pastime was made at his own grounds several months ago, when, in a race of 100 yards, over five hurdles, for £25 a side, he was defeated by Mr W. Booth of Manchester, by three quarters of a yard, after an excellent race. As judge of foot racing pace, allotting starts in handicaps, or as timekeeper, poor Martin had few equals – certainly no superior – and his decease has caused a vacancy which it will be difficult to supply. Within a short period he planned, laid out, and completed the Royal Oak Park Grounds, Manchester, upon which he lived to see some of the fastest races ever known brought to issue; but a short time ago he became mentally afflicted, and, after having made his escape from a private asylum at Buxton, Derbyshire, he subsequently proceeded to London, and died as above stated. Mr Martin was only 39 years of age, and he leaves a widow and a large family to mourn his loss.[118]

Martin left little money for his wife and family, with creditor, wine and spirits merchant Joseph Fildes, reclaiming the majority of Martin’s £2000 estate.[119] After his death his family and pedestrian friends continued his legacy, sharing the responsibilities of proprietor, referee, starter, stakeholder and timekeeper at the establishment until its eventual sale in September 1866.[120]

Although the Royal Oak Park Grounds are now a thing of the past, it is important to note that without the entrepreneurial vision and dedication of men, such as Martin, pedestrian amusements and competitions in Britain’s industrial cities would have been unable to survive. Martin laboriously promoted the sport through good times and bad, becoming an inspiration to a new generation of sporting entrepreneurs, and he truly deserved the title ‘wizard of pedestrianism’.

References

[1] Peter Bailey, Leisure and Class in Victorian England: Rational Recreation and the Contest for Control 1830-1885 (London: Redwood Burn, 1978), 166; Tony Collins and Wray Vamplew, ‘The Pub, The Drinks Trade and the Early Years of Modern Football’, The Sports Historian, 20, no.1 (2000): 2-3; Warren Roe, ‘The Athletic Capital of England: The White Lion Hackney Wick 1857-1875’, BSSH Bulletin, no. 17 (2003): 39-40.

[2]Manchester Guardian, October 11, 1845, 12; Dennis Brailsford, British Sport: a Social History (Cambridge: The Lutterworth Press, 1997), 68; Emma Lile, ‘Professional Pedestrianism in South Wales during the Nineteenth Century’, The Sports Historian, 20, no.2 (2000): 58; Mike Huggins, The Victorians and Sport (London: Hambledon and London, 2004), 47.

[3] Peter Lovesey, The Official Centenary of the AAA (London: Guiness Superlatives Ltd., 1979), 15; Stephen Hardy, ‘Entrepreneurs, Organizations, and the Sport Marketplace: Subjects in Search of Historians’, Journal of Sport History, no. 13 (1986): 23; Geoffrey T. Vincent, ‘”Stupid, Uninteresting and Inhuman” Pedestrianism in Canterbury 1860-1885’, Sporting Traditions, 18, no.1 (2001): 47.

[4] Parish registers for Frimley, 1590-1914 (0804127), George Martin baptised on September 24, 1826 in Frimley, Surrey to James Martin and Pandora (sic); Census Returns, George Martin 1841 (HO107/1074/1); (HO 107/2227); Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle (Hereinafter called Bell’s Life), 24 December 1848, 7; Marriage Certificate, George Martin and Alice Holden 1851 (MXE 606479).

[5] Penny Illustrated Paper, January 17, 1863, 43; Andrea Colli, The History of Family Business, 1850-2000 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 29; David Vincent, Bread, Knowledge and Freedom: A Study of Nineteenth-Century Working Class Autobiography (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982), 74; Sonya O. Rose, Limited Livelihoods: Gender and Class in Nineteenth-Century England (London: Routledge, 1992), 140; Rob Hadgraft, Deerfoot: Athletics’ Noble Savage: from Indian Reservation to Champion of the World (London: Desert Island Books, 2007), 58.

[6] Census Returns, 1841 (HO 107/1074/1), Hamlet of Frimley, George Martin, 15, ‘Shoe m j’; 1841 (HO 107/684/12), St Pancras, Marylebone, Clarence Gardens, James Martin, 45, Prudence Martin, 40, Mary Martin, 15, Maria Martin, 12, Henry Martin, 8, all noted as occupation ‘Shoe m’; 1851 (HO 107/1493), St Pancras, Marylebone, London, 47 Clarence Gardens, James Martin, 56, ‘Shoemaker’; Prudence Martin, 53; Henry Martin, 18, ‘Shoemaker’.

[7] Bell’s Life, August 19, 1841, 7; September 21, 1845, 7; October 19, 1845, 7.

[8] Bell’s Life, May 17, 1846, 6; February 21, 1847, 7; Manchester Guardian, May 27, 1858, 2.

[9] Sportsman, The Training Instructor (London: Sportsman Offices, 1885), 50-51.

[10] Bell’s Life, January 4, 1846, 7; November 1, 1846, 7; November 15, 1846, 7.

[11] Bell’s Life, January 7, 1844, 7; March 16, 1845, 7; January 11, 1846, 6; December 30, 1860, 7; September 22, 1861, 7; John Dugdale Astley, Fifty Years of my Life in the World of Sport at Home and Abroad (London: Hurst and Blackett, 1895), 282.

[12] Bell’s Life, January 11, 1846, 6; February 8, 1846, 6-7; March 15, 1846, 7; John Dugdale Astley, Fifty Years of my Life in the World of Sport at Home and Abroad (London: Hurst and Blackett, 1895), 282.

[13] George M. Young, Early Victorian England 1830-1865 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1951).

[14] Sportsman, The Training Instructor (London: Sportsman Offices, 1885), 75; Peter Lovesey, The Official Centenary of the AAA (London: Guiness Superlatives Ltd., 1979), 15.

[15] John Lowerson, Sport and the English Middle Classes (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995), 89; Dennis Brailsford, Sport: a Social History (Cambridge: The Lutterworth Press, 1997), 68; Tony Collins and Wray Vamplew, Mud, Sweat and Beers: A Cultural History of Sport and Alcohol (Oxford: Berg Publishing, 2002).

[16] Bell’s Life, September 21, 1845, 6; January 4, 1846, 7.

[17] Bell’s Life, January 4, 1846, 7.

[18] Bell’s Life, January 25, 1846, 6.

[19] Bell’s Life, February 22, 1846, 7; March 15, 1846, 7; April 12, 1846, 7; June 21, 1846, 7; July 5, 1846, 7.

[20] Bell’s Life, March 15, 1846, 7.

[21] Bell’s Life, July 5, 1846, 7.

[22] Bell’s Life, January 9, 1848, 7; Era, January 30, 1848, 6.

[23] Bell’s Life, March 19, 1848, 7; April 9, 1848, 6; April 16, 1848, 6.

[24] Era, January 2, 1848, 5; Bell’s Life, January 2, 1848, 7.

[25] Bell’s Life, June 25, 1848, 7; October 22, 1848, 6; Era, March 11, 1849, 6.

[26] Don Watson, ‘Popular Athletics on Victorian Tyneside’, The International Journal of the History of Sport, 11, no. 3 (1994): 485-494; Emma Lile, ‘Professional Pedestrianism in South Wales during the Nineteenth Century’, The Sports Historian, 20, no.2 (2000): 58.

[27] Bell’s Life, April 1, 1849, 6.

[28] Era, January 8, 1843, 10; Bell’s Life, August 20, 1848, 7; November 4, 1849, 7; November 25, 1849, 7.

[29] Bell’s Life, December 3, 1843, 8; January 25, 1846, 6.

[30] Bell’s Life, January 26, 1840, 7; May 16, 1841, 7; August 7, 1842, 6; November 12, 1843, 7; August 4, 1844, 7; November 16 1845, 7; March 22, 1846, 7; July 4, 1847, 7; February 27, 1848, 7; Era, March 11, 1849, 11.

[31] Bell’s Life, October 2, 1842, 7.

[32] Bell’s Life, July 1, 1849, 7; July 9, 1849, 6.

[33] Bell’s Life, July 15, 1849, 3.

[34] Bell’s Life, July 1, 1849, 7; David A. Jamieson, Powderhall and Pedestrianism (London: W. & A.K. Johnston Ltd, 1943), 35; Rob Hadgraft, Deerfoot: Athletics’ Noble Savage: from Indian Reservation to Champion of the World (London: Desert Island Books, 2007), 129.

[35] Bell’s Life, September 23, 1849, 7; September 24, 1849, 7; September 30, 1849, 7.

[36] Bell’s Life, October 7, 1849, 7.

[37] Rob Hadgraft, Deerfoot: Athletics’ Noble Savage: from Indian Reservation to Champion of the World (London: Desert Island Books, 2007), 129.

[38] Bell’s Life, September 17, 1848, 7; Era, August 11, 1850, 9.

[39] Bell’s Life, November 4, 1849, 7; Census Returns, George Martin 1851 (HO 107/2227).

[40] Marriage Certificate, George Martin and Alice Holden 1851 (MXE 606479) Era, 26 January 1851, 5; Manchester Guardian, 26 March 1851, 5; Census Returns, George Martin and Alice Holden 1851 (HO 107/2227); W. Whellan & Co., A New General Directory of Manchester and Salford, Together with the Principle Villages and Hamlets in the District (Manchester: Booth and Milthorp, 1852), 216.

[41] Frank Lewis Dowling, Fistiana: or, the Oracle of the Ring (London: Bell’s Life in London, 1841), 271-272.

[42] Bell’s Life, 3 August 1878, 8; Dave Day, ‘London Swimming Professors: Victorian Craftsmen and Aquatic Entrepreneurs’, Sport in History, 30, no.1 (2010): 35.

[43] Bell’s Life, March 18, 1855, 6.

[44] Bell’s Life, July 30, 1864, 7; December 22, 1866, 7; Rob Hadgraft, Beer and Brine: the Making of Walter George, Athletics’ First Superstar (London: Desert Island Books).

[45] Mike Huggins, The Victorians and Sport (London: Hambledon and London, 2004), 195.

[46] Bell’s Life, July 6, 1851, 7; August 31, 1851, 7; January 18, 1852, 6; February 4, 1852, 7; February 8, 1852, 6.

[47] Sportsman, The Training Instructor (London: Sportsman Offices, 1885), 71; John Henry Walsh, British Rural Sports; Comprising Shooting, Hunting, Coursing, Fishing, Hawking, Racing, Boating, and Pedestrianism, With All Rural Games and Amusements (London: Frederick Warne & Co., 1886), 615.

[48] Bell’s Life, February 11, 1849, 6.

[49] Bell’s Life, June 8, 1851, 7; August 22, 1851, 7.

[50] Manchester Guardian, March 5, 1853, 3; Scotsman, April 13, 1870, 7.

[51] George M. Young, Early Victorian England 1830-1865 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1951), 272; Peter Bailey, Leisure and Class in Victorian England: Rational Recreation and the Contest for Control 1830-1885 (London: Redwood Burn, 1978), 84; William J. Baker, ‘The State of British Sport History’, Journal of Sport History, 10, no.1 (1983): 59; Peter G. Mewett, ‘History in the Making and the Making of History: Stories and the Social Construction of a Sport’, Sporting Traditions, 17, no.1 (2000): 2-3; Geoffrey T. Vincent, ‘”Stupid, Uninteresting and Inhuman” Pedestrianism in Canterbury 1860-1885’, Sporting Traditions, 18, no.1 (2001): 47.

[52] Manchester Guardian, February 23, 1853, 5; Census Returns, 1861 (RG 9/2923), St Bartholomew, Salford, 14 Walter Street, George Martin, Head, 34, ‘trainer of pedestrians’, b. Surrey, York House; Alice Martin, Wife, 32, b. Lancashire, Manchester; James Martin, Son, 9, b. Lancaster, Manchester; George Martin, Son, 7, b. Middlesex, London; Thomas Martin, Son, 5, b. Middlesex, London; Elizabeth Martin, Daughter, 3, b. Lancaster, Salford; Harry Martin, Son, 1, b. Lancaster, Manchester; 1871 (RG 10/4054), St Michael, Manchester, 11 Brass Street, Alice Martin, Head, Widowed, 43, ‘Dress Maker’, b. Lancashire, Manchester; Alice Holden, Daughter, 9, b. Surrey, Handsworth.

[53] Bell’s Life, February 21, 1847, 5; Marriage Certificate, George Piers and Sarah Holden 1852 (MXF 084965); Manchester Guardian, October 9, 1852, 10.

[54] Census Returns, 1861 (RG 9/2950), Cathedral Church, Manchester, 4 Long Millgate ‘White Lion’, James Holden, Head, 62, ‘public house keeper’; Elizabeth Holden, Daughter, 20; George Pearse, Son-in-Law, 30, ‘letter-press printer’; Sarah Pearse, Daughter, 27; Sarah A. Pearse, Grand-child, 7; Elizabeth Pearse, Grand-child, 4; Isaac Slater, Slater’s Directory of Manchester (Manchester: Isaac Slater, 1855), 725; Will and Probate, James Holden, 16 August 1865 (G 3000 6/63).

[55] Era, June 7, 1857, 8; October 10, 1858, 10; October 17, 1858, 10; April 14, 1861, 10; Bell’s Life, August 27, 1864, 7; Manchester Guardian, October 28, 1861, 4.

[56] Essex Standard, March 31, 1854, 1; Daily News, 31 March 1854, 6; Examiner, April 1, 1854, 6; Hampshire Advertiser & Salisbury Guardian, April 1, 1854, 3; Era, April 2, 1854, 13; Derby Mercury, April 5, 1854, 7.

[57] Saint Pancras Parish Church, Register of Burials, Including Burials at Kentish Town Chapel, Dec 1854 (p90/pan1/191), 74.

[58] Bell’s Life, January 8, 1854, 6; August 20, 1854, 6; February 17, 1856, 6; October 26, 1856, 7; November 30, 1856, 7; December 14, 1856, 7; December 21, 1856, 7.

[59] Manchester Guardian, May 27, 1858, 2; Bell’s Life, October 17, 1858, 7; Census Returns, 1861 (RG 9/2923), St Bartholomew, Salford, 14 Walter Street, George Martin, Married, 34, ‘trainer of pedestrians’, b. Surrey, York House; Alice Martin, Wife, 32, b. Lancashire, Manchester; John Nevin, Boarder, 23, ‘pedestrian’, b. Middlesbrough; Charles Mower, 22, ‘bricklayer’, b. Norfolk, Denham; Salford Borough Gardens, Borough Inn 1861 (RG 9/2924); Rob Hadgraft, Deerfoot: Athletics’ Noble Savage: from Indian Reservation to Champion of the World (London: Desert Island Books, 2007), 58.

[60] Bell’s Life, June 17, 1860, 7; March 3, 1861, 6; The Times, October 10, 1861, 12; Illustrated Sporting News and Theatrical and Musical Review, March 29, 1862, 17.

[61] Era, May 12, 1861.

[62] New York Daily Tribune, June 11, 1861, 8.

[63] The Times, September 24, 1861, 10; October 9, 1861, 7; October 10, 1861, 12; October 15, 1861, 12; Bell’s Life, September 15, 1861, 7.

[64] The Times, June 26, 1861, 12.

[65] The Post Standard, November 10, 1997, page unknown; John Lucas, ‘Deerfoot in Britain: An Amazing Long Distance Runner, 1861-1863’, Journal of America Culture, 6, no. 3 (1983): 13.

[66] Bell’s Life, September 8, 1861, 6; The Racing Times, December 9, 1861, 389; Peter Lovesey, The Official Centenary of the AAA (London: Guiness Superlatives Ltd., 1979), 15; Alfred Rosling Bennett, London and Londoners in the Eighteen-Fifties and Sixties (Gloucestershire: Dodo Press, 2009), 351.

[67] Scotsman, September 10, 1861, 3; Bell’s Life, September 22, 1861, 7.

[68] Rob Hadgraft, Deerfoot: Athletics’ Noble Savage: from Indian Reservation to Champion of the World (London: Desert Island Books, 2007), 127.

[69] Bell’s Life, May 11, 1862, 7; Scotsman, August 18, 1862, 1.

[70] Bell’s Life, September 29, 1861, 6.

[71] Scotsman, October 15, 1861, 3; Bell’s Life, November 10, 1861, 7.

[72] The Times, October 7, 1861, 10; Bell’s Life, September 29, 1861, 3; October 20, 1861, 6; Manchester Guardian, October 28, 1861, 4.

[73] John Bull, December 7, 1861, 773.

[74] The Racing Post, December 9, 1861, 389; Licensed Victuallers’ Mirror, December 8, 1891, 581.

[75] Scotsman, October 2, 1861, 3; April 2, 1862, 3; John Lucas, ‘Deerfoot in Britain: An Amazing Long Distance Runner, 1861-1863’, Journal of America Culture, no. 3 (1983): 14.

[76] Era, September 22, 1861, 9; Bell’s Life, July 2, 1864, 4; Sports Quarterly Magazine, no. 6 (1978): 12-14; Edward Seldon Sears, Running Through the Ages (North Carolina: Macfarlane & Co., 2001), 139.

[77] Bell’s Life, September 22, 1861, 7; June 22, 1862, 2; Scotsman, April 1, 1862, 1; Birmingham Daily Post, September 18, 1862, 8.

[78] The Times, October 3, 1861, 7; Penny Illustrated Paper, October 19, 1861, 11; Warren Library Association, Warren Centennial: An Account of the Celebration at Warren, Pennsylvania (Pennsylvania: Warren Library Association, 1897), 121.

[79] John Bull, April 19, 1862, 256; Matthew Horace Hayes, Among Men and Horses (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1894), 18.

[80] Bell’s Life, 11 May 1862, 7.

[81] Illustrated Sporting News and Theatrical and Musical Review, May 17, 1862, 75; Era, May 18, 1862, 14; Bell’s Life, May 18, 1862, 7.

[82] Scotsman, August 18, 1862, 1.

[83] Rob Hadgraft, Deerfoot: Athletics’ Noble Savage: from Indian Reservation to Champion of the World (London: Desert Island Books, 2007), 133.

[84] Manchester Guardian, January 12, 1863, 3; Penny Illustrated, January 17, 1863, 43; Lancaster Gazette, and General Advertiser for Lancashire, Westmorland, Yorkshire &c., January 17, 1863, 6.

[85] Hull Packet and East Riding Times, June 13, 1862, 6; Bedford Times, cited in Rob Hadgraft, Deerfoot: Athletics’ Noble Savage: from Indian Reservation to Champion of the World (London: Desert Island Books, 2007), 133.

[86] John Bull, October 25, 1862, 685; Scotsman, October 25, 1862, 3; Bell’s Life, October 26, 1862, 7; New York Clipper, October 28 1862, 284; Standard, November 7 1862, 3; Matthew Horace Hayes, Among Men and Horses (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1894), 18.

[87] Scotsman, May 20, 1863, 3; John Lucas, ‘Deerfoot in Britain: An Amazing Long Distance Runner, 1861-1863’, Journal of America Culture, 6, no. 3 (1983): 16-17.

[88] Warren Library Association, Warren Centennial: An Account of the Celebration at Warren, Pennsylvania (Pennsylvania: Warren Library Association, 1897), 122-123; Washington Post, July 19, 1908, 15.

[89] John Bull, October 25, 1862, 685; New York Clipper, October 28, 1862, 284; Standard, November 7, 1862, 3.

[90] Bell’s Life, December 22, 1861, 6; July 19, 1863, 7.

[91] Sources: Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, May 11 1862, 7; May 18 1862, 7; May 25, 1862, 7; June 1, 1862, 6; June 8, 1862, 7; June 17, 1862, 7; June 22, 1862, 22; July 13, 1862, 7; July 27, 1862, 7; August 3, 1862, 6; August 10, 1862, 7; August 17, 1862, 7; John Bull, September 13, 1862, 581; Rob Hadgraft, Deerfoot: Athletics’ Noble Savage: from Indian Reservation to Champion of the World (London: Desert Island Books, 2007), 131.

[92] Charles Lang Neil, Walking: A Practical Guide to Pedestrianism for Athletes and Others (London: C. Arthur Pearson Ltd., 1903), 19; David A. Jamieson, Powderhall and Pedestrianism (London: W. & A.K. Johnston Ltd, 1943), 104.

[93] Bell’s Life, November 28, 1863, 7.

[94] Bell’s Life, February 22, 1857, 7; Era, February 22, 1857, 9; November 28, 1863, 7; April 24, 1864, 14.

[95] Bell’s Life, February 27, 1864, 7.

[96] Illustrated Sporting News and Theatrical and Musical Review, April 9, 1864, 54; April 23, 1864, 77.

[97] Manchester Guardian, April 18, 1864, 4; Illustrated Sporting News and Theatrical and Musical Review, April 23, 1864, 77.

[98] Era, April 17, 1864, 14.

[99] Era, April 24, 1864, 14.

[100] Bell’s Life, June 11, 1864, 7; Era, July 30, 1865, 14.

[101] Eagle Tavern/Grecian Theatre, City Road: Playbills and Illustrations, 1829-1899, Bishopsgate Institute Archives (London Collection Manuscripts/72); Robert Poole, Popular Leisure and the Music-Hall in Nineteenth-Century Bolton (Lancaster: University of Lancaster Press, 1982), 51-55.

[102] Era, March 13, 1864, 14; September 3, 1865, 1; Manchester Guardian, September 6, 1865, 1.

[103] Bell’s Life, May 13, 1865, 7.

[104] Sheffield & Rotherham Independent, June 27, 1864, 3.

[105] Bell’s Life, August 19, 1865, 8; Manchester Guardian, August 21, 1865, 4; Bob Phillips, ‘The Ancient Art of Mile Pacemaking’, Official Journal of the British Milers’ Club, 3, no. 16 (2004): 30.

[106] Bell’s Life, August 19, 1865, 8; Preston Guardian, August 26, 1865, 2; Penny Illustrated, August 26, 1865, 206.

[107] Bell’s Life, May 13, 1865, 7.

[108] Bell’s Life, September 16, 1865, 7; October 21, 1865, 7.

[109] Post Office, Post Office Directory of the Counties of Derby, Leicester, Rutland and Nottingham (London: Kelly & Co. 1876), 36; Notice of Admission, George Martin, September 1865, Derbyshire Record Office (Q/Asylum).

[110] Cambridge County Council, General Introduction: A History of County Asylums (Cambridge: Cambridge Council, 2011), 3.

[111] Joan Lane, A Social History of Medicine Health, healing and Disease in England, 1750-1950 (London: Routledge, 2001), 99.

[112] William Parry-Jones, ‘Asylums for the Mentally Ill in Historical Perspective’, Psychiatric Bulletin, no. 12 (1988): 407-408; David Wright, ‘Getting Out of the Asylum: Understanding the Confinement of the Insane in the Nineteenth Century’, Social History of Medicine, no. 10 (1997): 137.

[113] John K. Walton, ‘Lunacy in the Industrial Revolution: A Study of Asylum Admissions in Lancashire, 1848-1850’, Journal of Social History, no.13 (1979): 6.

[114]Medical Certificate, George Martin, September 1865, Derbyshire Record Office (Q/Asylum).

[115] Notice of Discharge or Removal of a Lunatic from a Licensed House, George Martin, October 3, 1865, Derbyshire Record Office (Q/Asylum).

[116] Death Certificate, George Martin, October 21, 1865 (DYC 866274); Manchester Guardian, October 23, 1865, 4; Leeds Mercury, October 24, 1865, 9.

[117] Bell’s Life, November 4, 1865, 7.

[118] Bell’s Life, October 28, 1865, 7.

[119] Will and Probate, (G 62/21; Manchester Guardian, November 10, 1866, 2.

[120] Manchester Guardian, August 25, 1866, 8; Bell’s Life, December 8, 1866, 7.