Please cite this article as:

Piper, G. Preparing for Success in the Sheffield Handicaps 1856-1899, In Day, D. (ed), Pedestrianism (Manchester: MMU Sport and Leisure History, 2014), 133-148.

______________________________________________________________

Preparing for success in the Sheffield Handicaps 1845-1899

Glenn Piper

______________________________________________________________

Introduction

There appear to be very few books or articles written about pedestrianism in Sheffield even though it was one of the great centres of professional athletics in Victorian times. Newspapers of the time are full of reports of pedestrian races and details of times, odds and amounts won. These facts are easy to find in sporting newspapers. One of the main publications was Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle. It was published weekly and had columns devoted to pedestrianism races all over the country. It is interesting to know who won a race and the time but for me it is much more fascinating to find out the human stories behind the bare facts. I was able to discover more about the world of pedestrianism in Sheffield due to a chance finding of a newspaper article whilst pursuing the athletic career of my great grandfather in the Sheffield Local Studies Library. I have been researching my family history for over a decade. I have been a member of the Sheffield and District Family History Society and various online genealogical groups and subscription sites

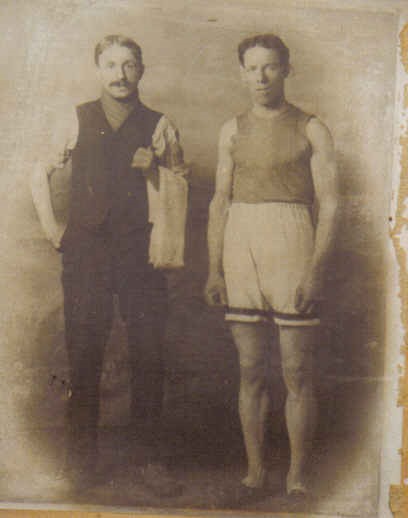

About eight years ago a distant relation of mine sent me a copy of a photograph she had found rolled up in the back of a drawer as she was clearing her mother’s house. It was this photograph of my great grandfather William Doubleday Piper and his trainer Harry Sharp in August 1914 that really sparked my interest in athletics history. How did they train? What did they wear? Where did they compete? All this and many more questions led me to Sheffield Local Studies Library and local newspaper reports of races in Edwardian times.

William ran for Sheffield United Harriers, cross country in the winter and track in the summer. Similar to 2013 in many ways, but in other ways so very different. I will never forget one report that mentions the Swinton Harriers and their objection to starting cross country races at 3 p.m. instead of 4 p.m. on a Saturday. Their objection was many of their club members worked down the pit until 2 p.m. and could not make a 3 p.m. start!

Figure 1. August 1914. William Piper and his coach Harry Sharp.

One morning I came across an article in the Green Un sports pages for 23 August 1913 entitled ‘Peds of the past-careers of old time runners. Number 11. Ink Smith.’ Suddenly a whole new world opened up. These were athletes competing prior to the days of Amateur Athletics. A world of pedestrianism. The more I read the more I wanted to know. Unfortunately work and family commitments intervened and I was unable to return to Sheffield for many years. However, some years later I acquired copies of the whole series of articles from a Sheffield historian (Keith Farnsworth). We had made contact via a genealogy mailing list and he very kindly lent me his copies. These articles provide much of the material for this talk. They were all published in the summer of 1913 in the ‘Green Un’. Some contain illustrations and they are all reproduced here.

The Sheffield Handicaps were famous throughout the land and even overseas in places such as America and Australia where newspapers reported on the races in great detail. They mainly took place during the period 1845-1899 although there are some examples of handicaps before and after these dates. Anyone with a turn of speed who had aspirations of fame and fortune dreamed of winning a Sheffield Handicap. Competitors would come from home and abroad to try their luck. One example shows how famous a winner would become.

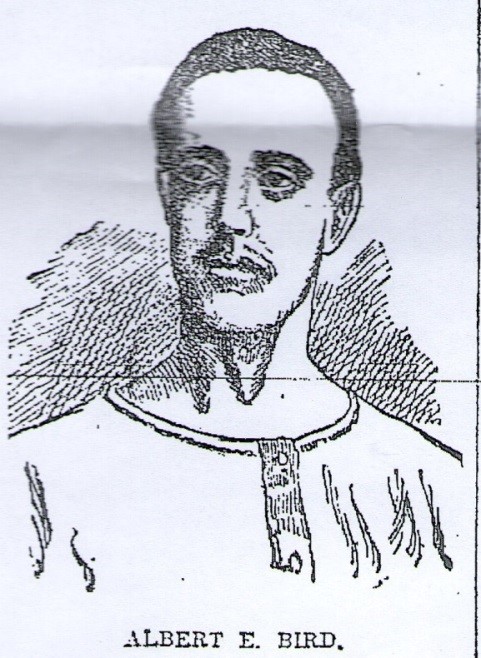

In September 1869, the Australian entrepreneur George Coppin, bought Albert Bird, promoted as the Champion Long Distance Runner of England and two other English Champions, Frank Hewitt, the English champion short distance runner and George Topley, the English champion long distance walker, to Australia for a 100 day professional running program. They sailed on the SS Lincolnshire arriving in Melbourne on the 16 December 1869 after a trip of eighty eight days. The arrival of the English pedestrians was promoted throughout all the Australian colonies. Their first appearance was on the 8 January 1870 at the Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG), and a crowd of 10,000 was in attendance to see the English champions’ race.

The 1913 article about Frank Hewitt gives little details that really bring him to life. It also shows that Frank was a little bit different from the ordinary class of pedestrian.

His unswerving consideration for his mother, coupled with his superior education and high musical qualifications always stamped Hewitt as being above the average of those with whom he was generally associated.[1]

In Australia, his fame and other talents led to amazing scenes.

The entire party was invited to Coppin’s Theatre, the largest hall in Melbourne. During the evening all three were introduced from the stage to the audience whose reception of the athletes knew no bounds. After order had been restored in the building it was announced that Mr Frank Hewitt, the English Champion from 100-1,000 yards would favour with a banjo recital. When concluded such a scene was enacted by the hearers as could never be compared to another of the kind. The people were almost frantic and the cries of encore were terrible for fully 20 minutes. In order to appease the clamour of an almost wild assembly he sang ‘Sally in the alley’ and later followed with ‘Pilgrim of Love.[2]

There cannot be many pedestrians of that time who had such musical talents!

In order to succeed at a Sheffield Handicap there were certain things you needed to make the dream a reality. One of the most important people involved was a good promoter. There were so many events being staged around the country and within Sheffield itself that a promoter was essential to bring in the crowds and the admission money.

All three illustrations from The Sydney Referee, 1908.

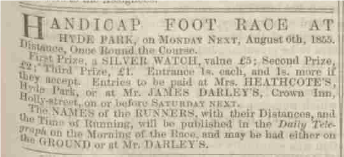

There were some notable promoters. First, in the early days of pedestrianism, were Samuel and Hannah Heathcote, proprietors of the Hyde Park Cricket Ground Inn from c1845-1862. In 1848, they spent £600-£800 improving the surface of the running track in Hyde Park order to make it ‘one of the best in England’. Hundreds of loads of broken rock were put in for a foundation and then a thick layer of earth ‘which by constant use of the rollers has become as firm as a rock.’[3] Samuel died around 1853 leaving Hannah a widow with four young children. Hannah did not retire from the sporting world butcarried on promoting events in this very masculine world for at least another nine years. She formed partnerships with other publicans, including James Darley of the Green Dragon.

Figure 2. Advert in the Sheffield Daily Telegraph, July 31, 1855.

Mrs Heathcote and James Darley appeared before the Sheffield Magistrates in 1857 charged with encouraging gaming and betting on Hyde Park by the promotion of foot races. There was much discussion about whether they were responsible for the gambling and a couple of brief sentences sheds light on the extent of Hannah’s involvement in the sport. ‘A parcel of young men’ (20 or 30) are kept at Hyde Park ‘merely for race running and making money by betting thereon’.[4] Heathcote and Darley were given a warning and told they would know how to act if they wanted their license renewed in the following year.

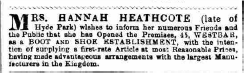

Her licence was in fact renewed many times. In the 1861 census she is a widow still living at the Hyde Park Cricket Ground and is an innkeeper. She has all four children living at home plus four house servants so she appears to be prospering in her role. Hannah is described in various reports as ‘Mrs Heathcote, the spirited proprietress of the Hyde Park Grounds’[5] and the ‘worthy proprietress’[6]. She would certainly have been respected and trusted as she was often the stakeholder in charge of the money collected in entry fees and admission. In 1863, James Boothroyd took over the running of the Hyde Park Cricket Ground Inn. Hannah had not retired but merely changed direction as this advertisement in the Sheffield and Rotherham Independent, 15 August 1863 shows

Hannah died in 1867 in Sheffield. Her obituary in the Sheffield Independent, 17 December 1867 states she died in her sixtieth year after a ‘long and patiently borne illness…deceased was a generous and kind hearted person who was loved and respected by a large circle of friends.’ There is no record of any will.

I have not been able to find any pictures of the running track or of the Heathcotes but these two images are of the front and reverse of a token described as an admission ticket or token.[7] Date is not known but it is inscribed Samuel Heathcote dating it to before 1853.

Another notable promoter from the latter quarter of the century was Ink Smith. He was interviewed by the Green Un in 1913.

Every Victorian schoolboy would know he was named after the battle of Inkerman and would instantly know his year of birth. Of course it was 1854 during the Crimean War. Ink was an ex-ped himself and took to managing various public houses in Sheffield. From 1879-1899 he organized over 300 handicaps at all the great racing venues in Sheffield. Entries came from far and wide, including America.[8]

The photograph from the Green Un is very revealing. Ink looks dapper in his top hat and moustache. Ink had great self-belief and an entrepreneurial spirit. Just listen to his own words spoken to the Green Un reporter in 1913.

Yes Sir, no 7 Titterton Street,Attercliffe is my present address.but if you put Ink Smith Sheffield that will find me without difficulty or delay……Mr Inkerman Smith, the greatest individual promoter of handicaps during the last or present century and without doubt one of the best authorities of the present day concerning the men who participated in those famous handicaps once held in this city and, which spread fame and fortune throughout the world of athletics.

At the time he was speaking these words in 1913 the glory days of the Sheffield handicaps were over. He was looking back on the good old days. By this date the Green Un has a weekly column called ‘With the Harriers’ devoted solely to reports of Amateur Athletics. The Heathcotes and Ink Smith are just two examples of successful promoters in Sheffield during the period 1845-1899.

There was a second crucial factor in success. An athlete needed to have other people support them through months of training and preparation. Like most modern Olympians, peds would rely on the support of their family but some had to overcome active discouragement from taking up this sport. It did have a certain reputation for attracting the rougher elements of society and the associated gambling and drinking could lead to violent scenes.

George ‘Punch’ Ellis did not tell his parents he had taken up professional running after cutting his indentures and his sister Mary recalled in 1913 how she would often run the gauntlet and secretly pass out his running clothes from the kitchen. His parents thought he was at work.

The main practical support for peds would come from a trainer who would pay for training and living expenses. They were often ex-pedestrians themselves and they would be heavily involved in the training and preparation of their man. Names such as James ‘Leggy’ Greaves, Brewer Smith, Pat Fagan and Pat Maher were well known in Sheffield. The training and preparation for a win in the Sheffield Handicap could take many months and even years. The Otaga Witness, a New Zealand paper, ran a whole article on Professional Runners and their tactics. It concludes by stating,

…the man who hopes to makes money out of a Sheffield Handicap must have wits as keen as a Sheffield razor[9]

The career of one famous pedestrian sheds some light on the activities of these trainers. Harry Shaw was born in 1856 and his father died when he was aged just ten. Harry dreamed of winning a Sheffield Handicap and being able to set up his mother properly. At the age of nineteen he ‘showed his ability as a runner to Pat and Thomas Maher who keenly interested themselves in his rough but surprising form.’[10] He was sent away to Carlton near Worksop to train and he made great progress. Training locations were often quite isolated and places such as Brigg, Lindrick Common, Worksop and Carlton became places where pedestrians ‘took their breathings’ away from prying eyes.

Harry became known as ‘Long Shaw’ due to his remarkable height (5 foot 11 inches) and his splayed feet. He entered the November 207 yard handicap at the Newhall Ground in 1876 and won the final by over half a yard. His trainers won handsomely as they backed him early at very long odds. Shaw received the prize money and also nearly £1,100 as he had backed himself early to win. His mother got a gold watch, a pair of gold spectacles and a very substantial gratuity. Harry promised her he would never run again and so returned to his trade in Sheffield.

You would have thought his trainers would celebrate and retire on their winnings but over a year later they were trying to entice Harry to try his luck ‘one more time.’ What did they do with the substantial amount of money they had won? Harry had promised his mother and he would not go against her wishes so he went to see her. Harry recalls his mother’s words clearly

Well lad thas dressed like a gentleman, tha seems to have plenty of good food, tha walks about dressed up without doing owt, and still tha has plenty of brass. Go thi way, care I, do what tha likes. I’ll let thee off thee word[11]

Harry started training for the Christmas Handicap of 1878 and I will return to his story a little later.

As the example of Harry Shaw shows, the training locations were often well away from Sheffield. The 1913 article on Ed Kinnear sheds more light on these locations. Kinnear was born in Quebec in 1869 but he returned to England with his parents when he was very young. He showed some form in local races and was ‘taken in hand’ by trainer Jimmy Young.

After being thoroughly trained and doing good time against the watch in several trials he was entered in the Christmas 120 yard handicap at the Victoria Grounds, Newcastle in 1895. He won, covering the distance in even time exactly. He was then under the care of Matt Storey of Sunderland. With this win and his entry into professionalism Kinnear decided to leave his trade and devote his undivided attentions to athletics. His preparation for succeeding events was carried out at the mecca of pedestrianism, Brigg, Lincolnshire. He was placed under the care of Sam Shirtcliffe of the Brocklesby Ox, whose ‘string’ at one time included such men as Harry Hutchins, Charley Ransome and other noted peds of the day, besides George Littlewood, who had previously occupied the self same house where he was quartered in Brigg.[12]

Another article in the same series about Jimmy Baytup shows how important the trainers were and gives a glimpse of a famous Sheffield venue in 1878.

Track running had now attached itself to Baytup and he came to live in Sheffield permanently. He was taken on by Sam Barker and Billy Boucher and went to train at Wickersley, near Rotherham with Jack Skelton…Skelton kept up the training and considered Baytup was equal to 4 yards inside evens. On the strength of this he was entered for the Doncaster St Ledger £100 Handicap at Hyde Park. Baytup was confident of his abilities and got on well with Skelton. However, when the world famous Pat Fagan come to see the results he was disappointed so they arranged for a secret trial at midnight on the Queens Ground. The parties all arrived there by 1am and Baytup was feeling fitter than ever. Fagan had lit all the lamps on the side of the track and he was timekeeper with Jim Bingham. When all was ready Baytup got a rattling start, but though never informed of the result, he had reason to know his effort had been no small surprise to them. After dressing, the lamps were speedily but quietly extinguished and the huge entrance gates were slowly drawn together again and the party quietly dispersed.[13]

Later in the same article we can read about his win in 1879

On the morning of September 8 1879 Baytup easily won his heat. It was customary to have an hour or so in bed prior to the final with nothing more than a cup of tea and half a slice of dry toast. Fagan (his trainer) was a bundle of nerves before the final. He said ‘I can’t stand this Jimmy lad; I’m going outside.’ The men parted and Fagan posted a young fellow on the fence to shout him results and in great agitation the old man paced up and down the road alone. Baytup won the race and poor old Pat Fagan could hardly contain himself. He threw his top hat in the air as the great crowd of spectators left the ground. He threw it so high he declares to this day ‘It never came down again’ Baytup won by 15 inches against the great Henry Hutchens.[14]

A third crucial factor in success was getting to grips with the betting and dodgy practices that came to surround pedestrian events. Thousands of pounds could be won or lost so it was no surprise that athletes, trainers and bookies might be tempted to influence results.

A common tactic was to pay an athlete to lose the race. The story of Andrew Lillis illustrates the problems and temptations. He was widely regarded as one of the best sprinters of his generation but he never won a Sheffield Handicap. He was married to the niece of Pat Maher (one of the most famous and influential trainers) and in 1880 he was in serious training for the £100 Hyde Park Handicap. He intended to win this one (for a change) and put his name in the record books but in an unguarded moment he let his wife know his intentions. She went to her uncle who knew he would be ruined if Lillis run to the best of his ability. Lillis was now ‘twix the devil and the deep blue sea.’ His wife threatened to leave him if he won. If he lost he would ‘be cried down and the poorer for his effort.’ He decided on the only sensible course of action. He followed the advice of his wife and Pat Maher made a profit of £2,500. The Green Un claimed in 1913 that ‘he was too easily got at by the bookies or secretly accepted odds against himself.’[15]

The census returns show Lillis was the child of Irish labourers and he himself was a general labourer in 1891. He did not have a trade or a skill so he would not have been earning a great deal. If Lillis could speak he might say that making a lot of money was really a success. We do not know how much Lillis made from throwing races but he certainly did not live long to enjoy much of his earnings. He died sometime between 1891 and 1901 leaving a widow and four children.

It does seem a recurring theme that athletes could win a lot of money and lose it just as easily. This happened to Arthur Wharton and his winnings went on drink. He ended up a penniless alcoholic and died in 1930. It is only in the last decade or so that his achievements have been remembered and recognized. His unmarked grave in Edlington Cemetary near Doncaster has finally been marked with a headstone He was a great sprinter and one of the first black professional football players and was inducted into the English Football Hall of Fame in 2003.

Tom Deighton went against the grain somewhat as he prudently put aside some of his winnings and this was considered worthy of special mention.

The season of Deighton’s public career was now drawing to a close and he was nearly 30 years old. He was not without means for after winning his handicap and acting on the kind advice of his friend and staunch supporter, William Unwin, he deposited several hundred in the bank for later requirements in life. He practically ceased to run and being unmarried and of a very homely position he went to live with his parents at the Coach and Horses Hotel, Chapeltown, which they occupied for more than 40 years.[16]

The article about Jimmy Baytup gives us a clue to the amounts of money involved. It states Baytup was offered £400 to lose a race, which he duly accepted. Baytup did not always accept these offers and he won two Sheffield Handicaps in 1878 and 1879.

The American newspaper, The Mansfield News includes some memories of old time runners. It mentions the case of the American runner Piper Donovan who entered the Sheffield Handicaps four years in a row. To everyone it looked as though he ran his heart out but he came nowhere. This was because he had four or five pounds of lead in his shoes. In the fifth year, Donovan returned and was backed by huge amounts of money. He carried no extra weight this year and won hands down. The paper mentions Donovan and his trainer returned with $11,000 in stake money plus about $50,000 in side bets.[17] These are huge amounts of money by any standard. Other American papers note how Americans had gone to great trouble and expense to get to England and actually win a Sheffield Handicap. The reports do not agree on the exact number but figures of between seven and nine American winners are quoted

The examples of Lillis, Shaw, Baytup and Donovan show how engrained gambling was in pedestrianism. Some athletes refused to run crooked and ran to win. To do this they had to train hard and avoid all temptations. This is where we return to the story of Harry Shaw who had been persuaded to come out of retirement after getting approval from his mother.

He absolutely refused to give in to bribes at the Christmas Handicap in 1878. A lot of people stood to lose serious money if Shaw won and the word got around after the heats that trouble was brewing and Shaw would be ‘upset’. Shaw managed to get a lot of his friends from Sheffield to the course to give him protection. He was ‘escorted’ from the dressing room for the semi-final and other people were posted all around the track. Shaw won and, as was the custom, at 3 p.m. the gates were opened to the public and the attendance swelled to over 20,000. (It was free admission after 3 p.m.) At 3.30 p.m. the bell was rung to clear the course. The race got off to a good start then the mob closed in like an avalanche upon the runners. Despite this Shaw finished in first place and the press were unanimous in describing this as the most exciting and highly sensational race in the history of the Sheffield Handicaps.

Shaw almost predictably became a publican and, as was common, his fortune left him quite quickly. The article does not mention if he gambled or drank it away. Also Shaw, like many successful sportsmen, acquired lots of followers or spongers. One day Shaw must have seen the light and decided to teach the spongers a lesson. He set up a bet that he deliberately lost. His forfeit was to provide an open supper for his ‘friends’. The friends tucked in and were enjoying the free food when half way through another man arrived late and started whinnying like a horse and saying ‘way hoss’ and such like. It soon leaked out that the food was horseflesh instead of beef. The trick was talked about in all the public houses in town and Shaw had rid himself of their company.

Shaw did not remain a publican like many ex peds. He worked as a fireman for a seven tonne steam hammer then moved to Durham where he became a great advocate of teetotalism and did evangelical work in the local community. He acquired a love of antique china and passed a collection onto his children when he died in 1909.[18]

There was another factor in success in a Sheffield Handicap. An athlete needed a true and honest starter if he was to compete on level terms. Someone who could not be bribed or influenced. One such man shines out. Tom Wilkinson was in great demand as a starter at professional meetings in Sheffield and throughout England. Later he was in great demand at Amateur meetings. ‘He was a noted sprinter but better known all over the world as the cleverest and most astute starter of a handicap that ever held a pistol’

‘He frequently received public congratulations on the strength of mind amongst so many temptations. He was never known to put a single penny on man, horse or dog racing.’[19] He was a man of unimpeachable integrity. He refused offers of up to £100 to go crooked.[20] He was born in 1835 and during his long and honourable career started more handicaps than any man that ever lived. He was quiet, plain, unassuming man whom everyone liked. If you wanted to win the Handicap you needed a starter like honest Tom

For over fifty years Sheffield Handicaps were famous throughout the land. Reports of the races were in newspapers all over the world. Promoters, family, trainers, training camps and honest officials were all important factors in preparing for success in the Sheffield Handicaps. If you reached the final, at the start of the race you had to keep your nerve when thousands of pounds could be won or lost. Reputations could be made or broken in the space of minutes. Some of the classic lines from Kipling are pertinent

IF you can keep your head when all about you are losing theirs…

If you can fill the unforgiving minute with sixty seconds’ worth of distance run,[21]

In all the thousands of reports of races and times there are very few that give a sense of what it was like to actually be at a Sheffield Handicap. I have found just one wonderful example. This was written by Hal Lowther and is worth quoting in some detail for its vivid language and Dickensian descriptions.

The potato engines were doing a roaring trade and bookmakers shouting themselves hoarse. At the top side of the ground parallel with the straight is a long bank of earth, sheltered by a high wall where thousands congregated. ‘there were burly men with purple faces, aproned artisans, emaciated youths with skeleton frames, the chattering of whose teeth out rivalled the rattle of dice boxes in full swing just below.’ He describes the most miserably clad spectators; their language ‘appeared to possess more blood than did their bodies…nearly all of them were owners of leashed dogs, more carefully wrapped up, fed and cared for than their starving masters! Oh, what a piece of work is man!’ As the runners entered ‘each one followed by his trainer and principal backer, how the crowd scanned them and criticised their appearance. The survey produced a roar of offers, for and against from the metallic brigade. The men stripped off their overcoats and wraps and, after a preliminary sprint, finally toed their respective marks. For a moment a breathless hush seemed to stagnate every form, and so deep and intense was the silence, each one fancied he could hear nothing but the beating of his neighbours heart-when crash! A pistol shot loosens every tongue and a Babel of sounds goes up in the air like a hell broke loose which culminates..in an earthquake of voices, as the winning man breasts the tape!’[22]

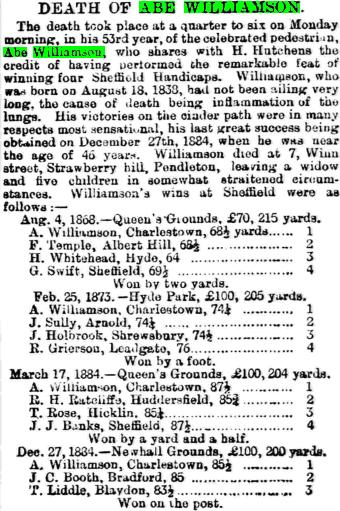

To win one Handicap was a great achievement and any more than that most unusual. Only two men won an incredible four Sheffield handicaps. One was the great Harry Hutchens and the other Abe Williamson. The latter won his four handicaps over a period of twenty-six years. His final victory, in 1884, came at the age of forty-six.

Sheffield Independent, February 25, 1891

I hope this article inspires more people to find out about the life and times of the pedestrians who took part in the famous Sheffield handicaps. Further research in local newspapers might help to reveal more about the life and times of the Sheffield peds.

References

[1] Green Un, Summer 1913.

[2] Green Un, Summer 1913.

[3] Era, April 30, 1848.

[4] Sheffield Independent, August 29, 1857.

[5] Kendal Mercury, September 24, 1859.

[6] Sheffield Independent, March 17, 1862.

[7] Sold on http://www.noble.com.au

[8] York Herald, February 6, 1899.

[9] Otago Witness, April 24, 1890.

[10] Green Un, Summer 1913.

[11] Green Un, Summer 1913.

[12] Green Un, Summer 1913.

[13] Green Un, Summer 1913.

[14] Green Un, Summer 1913.

[15] Green Un, Summer 1913.

[16] Green Un, Summer 1913.

[17] Mansfield Reporter, December 11, 1911.

[18] Green Un, Summer 1913.

[19] Green Un, Summer 1913.

[20] Wanganui Herald, March 31, 1890.

[21] Rudyard Kipling, Rewards and Fairies (1910).

[22] Sporting Mirror, April 1883.

Good morning,

Would you have any knowledge of a Les Smith who won the Sheffield Handicap at Belgian Relief Sports on 24/5/1915. A friend has the winning medal from that race. I have a photo of it for reference.

Regards

Glen

Glen, this is the first time I have seen this about William. It’s fascinating – and oh those Piper legs – still in the family. Best wishes Alison