Chastleton House, built in 1607 is most famous for an episode during The English Civil War in which a loyal wife duped Roundhead soldiers to save the plight of her husband. However, nestling in the gorgeous Cotswold countryside between Chipping Norton and Stow on the Wold, it is also the unlikely setting for the codification of rules of one the UK’s oldest sports.

Chastleton House in Oxfordshire

The rules of Croquet were first codified at Chastleton in 1866, by a former resident, Walter Jones Whitmore, who was born at the house in 1831.

Always looking for an opportunity, after dropping out at Oxford [amongst other things he had invented a ‘bootlace winder’ in 1864[, he turned his attention to Croquet and it quickly became all consuming. He installed two lawns and realising that the rules seemed to vary considerably amongst the various makers of equipment, he set about creating rules and tactics of his own. In December 1866 The Field magazine began a series of three articles by Whitmore on Croquet tactics and in May 1868, they were published in book form with hand-coloured diagrams. Until this point in time, there were no tactics or standard rules, therefore Whitmore can justifiably be considered to be, ‘The father of competitive Croquet’, having by then organised the first Croquet tournament at Evesham in 1867. Such was the tournament, it is now listed in the records as the ‘First Open Championship’, which Whitmore duly won, thus becoming the first champion. The first international event however, would have to wait until 1925, when England played Australia in the inaugural ‘MacRobertson International Croquet Shield’. It is currently competed for by Australia, England, New Zealand and the USA and is played in rotation every four years.

The MacRobertson Shield

Working in conjunction with The Field‘s editor J.H.Walsh, Whitmore helped to found the All England Croquet Club (AECC), but left soon after due to a difference of opinion in 1869; the club later went on to share its home with ‘The Lawn Tennis Association at Wimbledon until 1922. Walter founded a new club in direct competition called The National Croquet Club (NCC), where he further revised the laws and rules of the game.

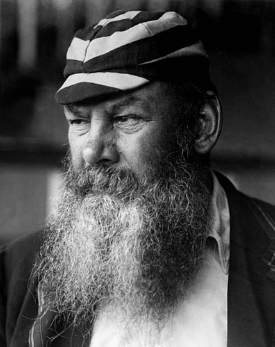

Walter Jones Whitmore

Although both clubs were now established separately, there were very few differences between them, thus in 1869, the NCC proposed a conference to draw up a code of the laws, which the AECC agreed to do. After several initial differences of opinion, the new code known as The Conference Laws was adopted in 1870 and then revised two years later. In 1872 however, Whitmore became seriously ill; he had developed cancer of the throat and underwent treatment, but on returning from his convalescence in Jersey, he collapsed at Chastleton and sadly passed away at the age of 41.

The Croquet tactics booklet published in 1868

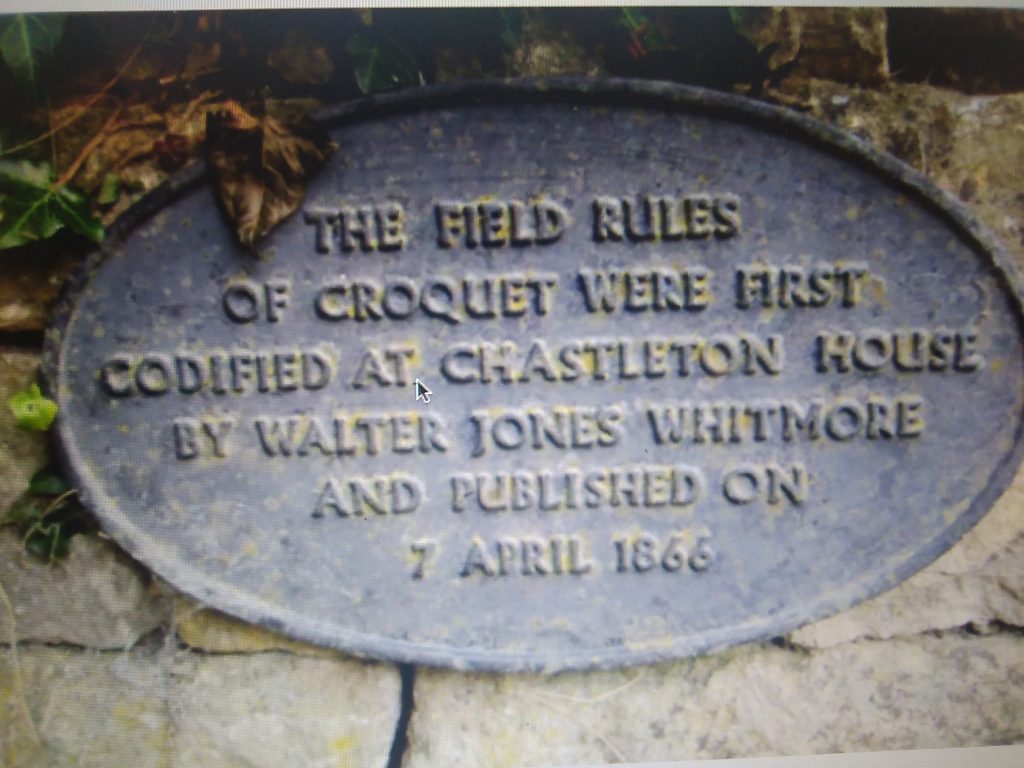

A small modest plaque, next to one of the croquet lawns, is all there is to commemorate the important contribution to the sport made by Jones. The plaque, unveiled in 1999 by John Solomon, the then President of The Croquet Association, acknowledged Whitmore as:

Possibly the most important figure in the establishment and development of Croquet.

Quoting Arthur Lillie, Whitmore’s contemporary who wrote ‘Croquet: its History and Secrets’ in 1897, the president summed up Whitmore’s massive contribution saying that:

He transformed the game from the silliest of open air pastimes to the most intellectual one‘Importantly’ said Solomon, ‘a great Victorian pioneer and innovator has been brought back into focus and for the first time, honoured on his home ground.’

The plaque commemorating the codification in 1866

The most absorbing research took place at Chastleton in the early 80’s and it was partly author David Prichard’s account of his work in preparation for The History of Croquet, published in 1981, that led to the Croquet Association’s initiative. The National Trust, who took over the running of Chastleton House in 1991, hope to offer ‘Croquet weekends’ in 2023 and will be producing a pamphlet with the rules and history of ‘Croquet at Chastleton’ to enable players to learn more.

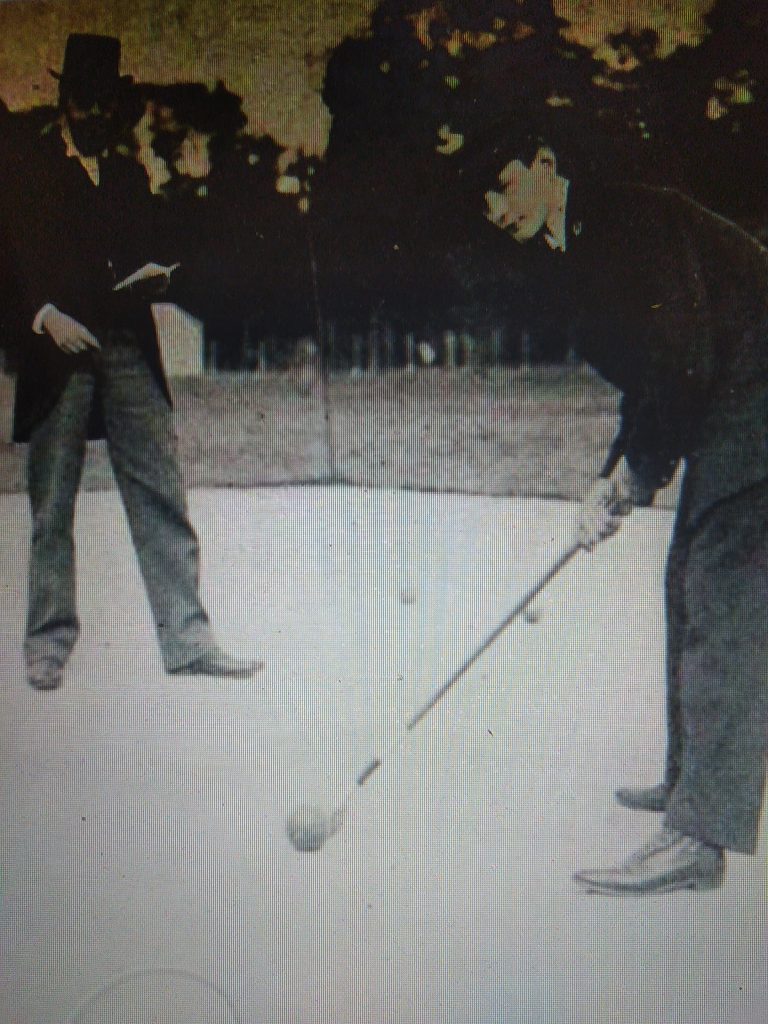

There is a debate regarding where the game originated, but Croquet became hugely popular in England during the 1860’s and it was enthusiastically adopted and promoted by The Earl of Essex , who held lavish croquet parties at his stately home in Hertfordshire and even launched his own croquet set. As a result of the codification at Chastleton, John Jaques printed 65,000 copies of The Laws and Regulations of the Game and it became extremely popular across the empire and no doubt, one of the main attractions, for some, was that it could be played by both sexes. However, it was the invention of the cylinder lawn mower that undoubtedly helped the game to become popular, since Croquet can only be played well on a flat and even surface.

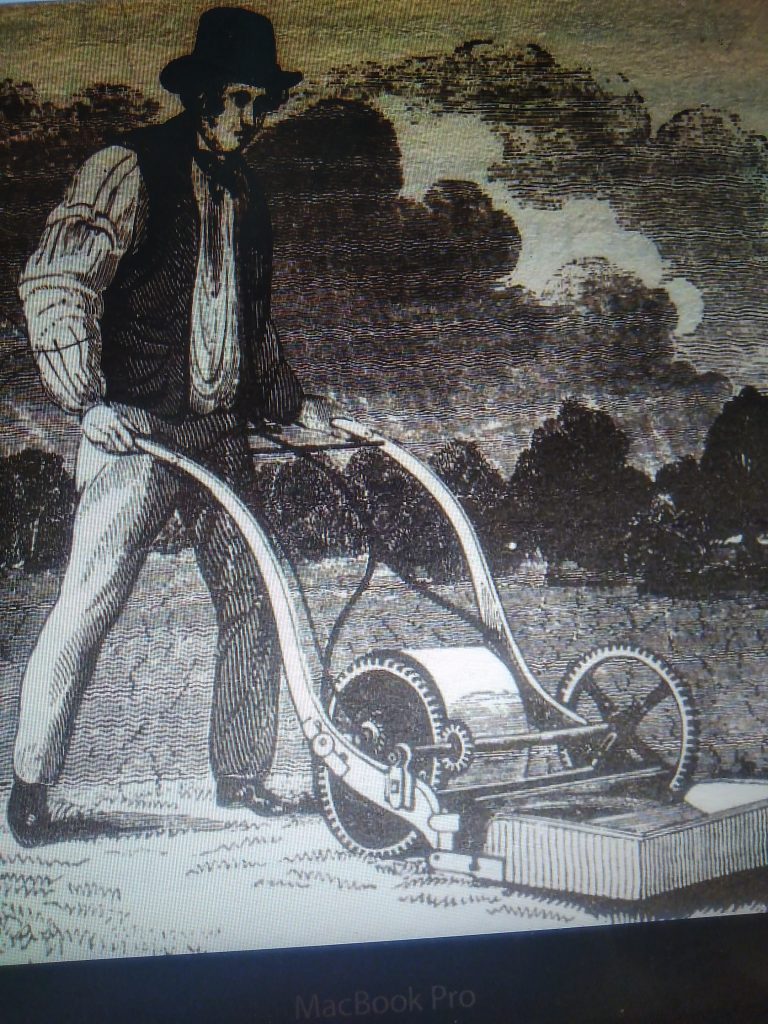

In 1830 Englishman Edwin Beard Budding from Gloucestershire, was granted the patent for the first ‘mechanical lawn mower’. He initially thought of the idea after seeing a cylinder mechanism that cut cloth after weaving. Budding’s patent stated:

Country gentlemen may find in using my machine themselves an amusing and healthy exercise

The Cylinder Lawn Mower patented in 1830

He intended the machine to be for large estates like the London Zoological gardens, however, as a result of his invention, some sports were able to develop more quickly and some historians have referred to this as ‘The Budding effect’. Sports such as Lawn Bowls, Cricket, Lawn Tennis and Croquet all started to take advantage of this new technology and after the patent was terminated in 1850, it was free reign for all to furhter innovate. Ransomes of Ipswich purchased the first manufacturing license from Budding in 1832 and over 180 years later is still a major UK manufacturing centre for precision mowers for sports grounds. In 1859, Thomas Green created the Silens Messor [meaning silent operation] which was a huge success, using chains to transmit power from rollers, it was quietier to use and it also came with a box to collect the grass cuttings. This was the first commercially successful mower and well over a million were produced up until the 1930’s.

Edward Budding

At the 1900 Paris Summer Olympics, three Croquet events took place; doubles, one ball singles and the two ball singles. Seven men and three women took part. all French, who therefore won all the medals. It is unclear as to why there were not any players from Britain taking part, but it would be the only time where croquet was part of the official programme. In more recent times, there has been a move to try and include the sport in the Commonwealth Games in 2026, but a barrier may be the requirement to sign up to the World anti-doping Agency’s testing policy, which could prove a major headache for an amateur sport run primarily by volunteers. Interestingly, ‘Golf Croquet’, a simpler version of the sport, which was invented by The Edwardians, exported to the colonies and then largely forgotten, has re- emerged. The World Championships, which were first held in 1996, took place in August 2022 at the Sussex County Club in Southwick, with 22 nations taking part.

Croquet in the 1900 Olympics

A contributing factor for the rules and laws of many well known games to be standardised and subsequently codified may have been the improvements in various transport networks and with Britain’s position at the centre of the empire, created a perfect storm for the creation of many national sporting institutions that still exist today. This soon led to domestic and later international competition across all sports.

Golf Croquet invented by the Edwardians, re emerged in 1996

The Football Association, founded in 1863, came into existence producing a set of rules largely based on those used at Cambridge University. The world’s oldest football competition, the FA Cup,was first contested in 1872 and the first official international football match took place that year between England and Scotland at Partick, near Glasgow. The Rugby Football Union was set up in 1871 and created an initial set of laws, adopting those first used at Rugby School, the first international rugby match also took place that year between England and Scotland in Edinburgh. Initially codified by the MCC [set up in 1744] in 1875, Tennis became instantly popular and rules were adopted by The All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club, followed by the first Championships held at Wimbledon in 1877. The first Hockey Association was formed in 1876 and drew up a formal set of rules, but only survived for six years. In 1886 it was revived by nine clubs, however, the first international match was between Wales and Ireland in 1895, a few months before England played their first match against Ireland. Lawn Bowls was first set up in Scotland in 1892, before the English Bowling Association was formed in 1903, with Victorian cricketer, W.G. Grace as its first president; international competition began in 1905. The first Open Golf championship took place in 1860 at Prestwick Golf Club in Ayrshire and was played there every year, until 1872 when a decision was made to rotate the competition around three different clubs in Scotland. The introduction of a new trophy, The Claret Jug, has been contested every year since then. In 1897, the Society of St Andrews Golfers, codified the rules and as a result, the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews, gradually took over the running of golf in the UK. The first non-British winner was the Frenchman, Arnaud Massey in 1907. Despite the first codification of Netball rules taking place in 1901, it would take until 1924 for the first National Governing Body to be established in New Zealand and it would be 1938 before the first international match between Australia and New Zealand took place. However, it was 1960 before rules were officially standardised across all the playing nations.

From around 1860, Codification Mania swept the country and many took the decision to codify and standardise the rules and laws of their sports in an effort to create order before anyone else did. More often than not those creating rules were from Oxbridge, like Whitmore Jones, and were therefore, gentleman amateurs and they very much aimed the codification at players who were themselves gentleman amateurs.

‘The concept of the gentleman amateur’, argues Duncan Stone in his 2021 article, Deconstructing the Gentleman Amateur ‘is an important aspect of upper and middle class Victorian and Edwardian male identity’ and was epitomised by the ‘Father of Cricket’, Dr W.G Grace, who was a doctor, landowner and family man, but in the late 19th century, probably the most famous cricketer in the world, who could boast a fan base of millions. In the context of his amateurism, his contribution to sport seems all the more incredible and as ‘the greatest of gentlemen, he did more to shape the future of the game than anyone else’, argues writer and journalist Will Magee in 2016 and yet,’ he was not a professional and therefore played the game for the love of it!’

W.G Grace president of The Lawn Bowls Association in 1903

Britain pioneered many of the sports which later spread around the Empire and the world and Mike Huggins in his excellent book, The Victorians and Sport [2004] suggests that,

The Victorians re-emphasised the spirit of competition and the need for a commercial approach to profit and applied such notions to their sports.Active participation in sport was also seen is improving the health of those in sedentary urban occupations, providing physical, mental and moral well-being.‘Britain was the cradle of the sporting world and its rise as the leading economic world power aided the export of its modern sports and the development of widely-played ball games’, says Huggins and he believes that ‘this was a distinctive achievement of Victorian Britain, and the British taught the world to play them’.

The opportunities for the ordinary working class man to take part in any form of sport, however, was very limited in the 19th and early 20th century and it would take many years before organised sport became available to the common man and even longer for the common woman.

Article Ⓒ of Bill Williams