The Life Saving Society (LSS) founded in 1891, promoted resuscitation, rescue techniques, and distinguished from the outset by its openness to international contacts. It’s animator and president William Henry, a guest on several occasions in Continental clubs, also advocated this attitude. Promoting the social aims of swimming, raising awareness about the possibility of saving lives, but also organizing competitions as attraction to diffuse the practice, were therefore cornerstones of this philosophy, and not only the domestic but also foreign press called him an apostolate. The competitions could encourage the learning of swimming, a humanitarian art as well as source of pleasure and enjoyment. Therefore, champions gladly joined the initiatives of LSS.

In the early years of the twentieth century, the LSS promoted various and profitable tours, aiming to establish branches in as many cities as possible. In 1901 in Italy, animated by his sincere commitment and passion, Eng. Arturo Passerini of Ancona founded the Natatorium, the first Italian branch of the LSS. A noteworthy achievement, not least due to the many sporting and cultural differences between the two countries. It was hard for Italian promoters of sports to accept the sports games of both English and Protestant origins, because Britain appeared politically hostile and against a possible expansion of Italian influence. The press accentuated these apparent incompatibilities, juxtaposing the Italian imagination and creativity against the scientific attitude and the method of Britons. In 1894 the newspaper La Bicicletta hinted at the ‘feeling of race’ stronger than the concept of homeland, for which Latin liveliness and spontaneity had to combat the excess of logics present in Anglo-Saxon culture. It concluded, that it is better to have a natural athletic talent than to generate an athletic through systematic training procedures, as was supposedly happening in England.

- Passerini Arturo

Passerini and other purposeful Italian swimming executives, residing mostly in urban centres, were in the minority looking with admiration to Britons, the masters of swimming and tireless promoters of life saving. Swimming in Italy had very few facilities, and the sport was mostly held in rivers, lakes and along the coasts. Not surprisingly, in its official title, the Italian federation grouped the societies of rari nantes (rare swimmers).

The LSS therefore organized an intense two-week tour, from 17th August to 1st September, unfortunately, at the last minute William Henry was unable to accompany the tour. The great John Jarvis, world champion by virtue of his victories at the Paris Olympics in 1900, led the expedition, which comprised of some second-class swimmers such as Blackshaw, Austin and Sanders, also included was F. Clarke of the Sporting Life, together with the famous publicist Archibald Sinclair .

- John Jarvis

- Jarvis in Naples, 1901

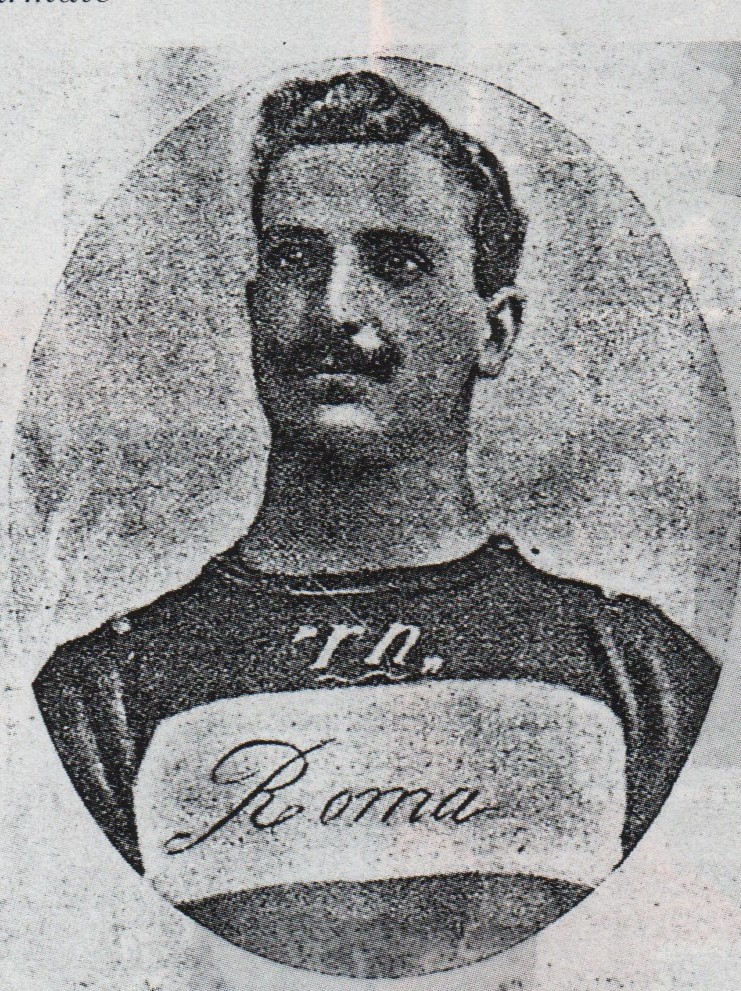

The stages of the tour were Turin, Genoa, Naples, Rome and Milan, the only city which, in addition to making available a wooden swim-house and the basin on the Naviglio river in Restocco near Milan, was capable of hosting exhibitions in the Diana bath. Just before the visit of the LSS to Turin, Milan opened its lifesaving sections. Everywhere, people cheered the English champions enthusiastically. The Gazzetta dello Sport, then bi-weekly but already the first Italian sporting newspaper, covered the event with many articles. Colonies of active English sport residents in Italy participated in these meetings. In Genoa, James Spensley, one of the founders of the Genoa Football and Cricket Club, and still an active goalkeeper of the team, made his celebrated appearance. In addition to his highly admired feats of rescue, Jarvis always emerged as the best swimmer, defeating the elite of Italian swimming, beating the national champion Bozzo (he had gained the title on August 16) in Genoa, the brilliant Lombardy champion Enrico Perlo in Milan, and Romeo Tofani in Rome, losing by some 400m over a 4000m course. Vincenzo Altieri of Rome, who had become famous when on 11 July he completed a swim of over 47 kilometers in the Tiber river and challenged Jarvis to 40 kilometers. The English champion elegantly replied that this test should have been properly prepared, and declined.

- Altieri Vincenzo

- Bozzo Coriolano

Cultural differences and clichés emerged however with the lawyer Mira in Milan, at the farewell banquet, stating, with little diplomatic sense, that Italians and Englishmen would never enter the war on opposite fronts. Sporting Life 28 August made a glaring error by naming, in a short article on the races of Genoa, that these races were seen as valid for the Championship of Switzerland, confusing Genoa and Geneva. Elsewhere, it reported on a very enjoyable tour, accepting the challenge of the Gazzetta dello Sport, for five Italian swimmers to compete against five British swimmers, in the foreseeable future.

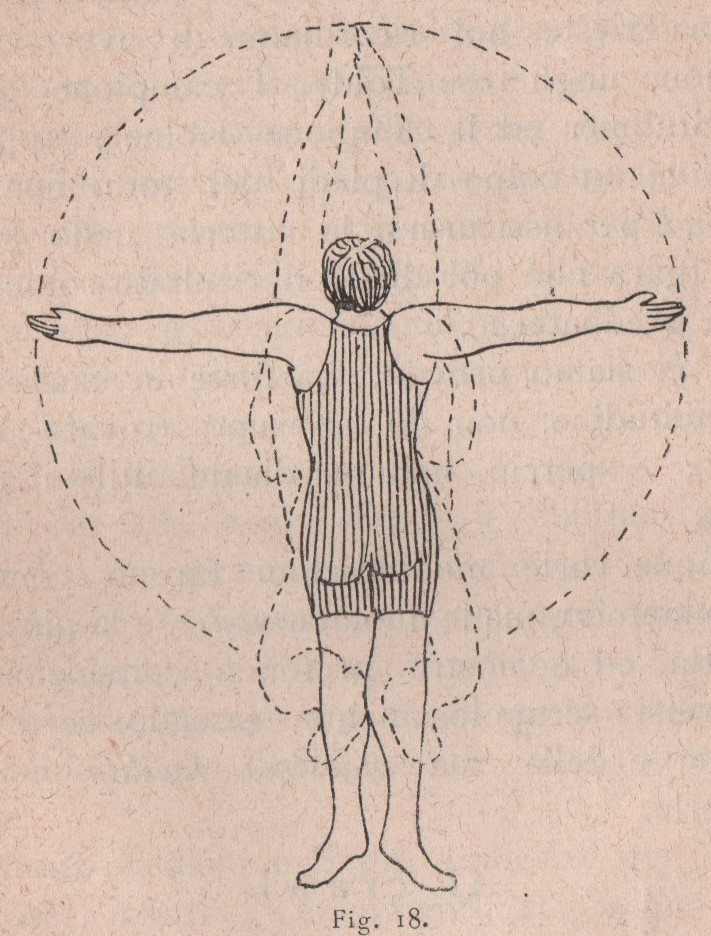

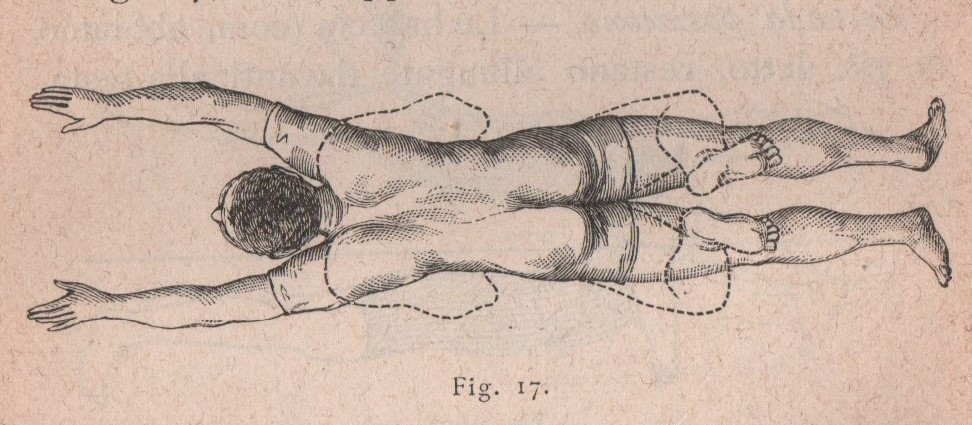

For its part, the Italian press paid deserved tribute to Jarvis, but judged the other English swimmers on the same lines as the Italians. La Stampa of Turin and Corriere della Sera of Milan defended the natural Italian swimming system, copied from animals and anchored to a frog movement with the non-classical gait, with open legs, but quickly paralleled after the action of a marked push. The Italian system was natural, the English one, essentially an over arm side stroke, developed by Jarvis with a peculiar aesthetic, rational and constructed scissor kick .was considered mechanical. Corriere della Sera also stressed that Jarvis was not built the same as other swimmers and reiterated that the Italian swimmers had seemed like “little frogs” against human machines perfectly built by training as typically happened in British culture. In sum, the Italians preferred to remain swimmers anchored to the instinct and not to undergo artificial training work.

In the following years, some swimmers such as Amilcare Beretta, one of the protagonists of the races in Milan, and other prominent athletes learned the over arm side stroke, which was beginning to emerge not only in Italy, thus leaving aside any prejudices. It is not surprising that the proposal by the captain of vessel Olivari, in April 1901 and repeated in 1904, for the adoption of a system that combined natural familiarity with water with the synchronized, but not rapid, movements of legs and feet, that an unconscious version of double over arm side stroke never had imitators beyond Olivari.

Article © Gherardo Bonini

![“And then we were boycotted” <br> New discoveries about the birth of women’s football in Italy [1933] <br> Part 6](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/PP-banner-maker-4-440x264.jpg)