During the nineteenth century, which was marked by the rise of sport as a social phenomenon, several men, and more rarely women, used their physical abilities to gain fame and money through weightlifting, wrestling or tests of strength. They announced their arrival in the cities and villages through posters and placards, promoting themselves with such epithets as ‘the strongest man in the world’, ‘the monarch of strength’ or, self-styled using heroic names such as the ‘new Hercules’, ‘Samson of’ the West’ and other labels.

With the emergence of modern sport, strength athletics slowly began to standardize its rules, competitions and gatherings by using standard weightlifting equipment, establishing sporting associations and forming reliable juries. After all, only through a properly regulated competition could one attempt to find out who really was the strongest man in Europe or the world.

Among the great metropolises, like Paris, Munich, Prague, New York, and St. Petersburg, Vienna emerged as one of the most active in strength sports. Often, restaurants, taverns and breweries offered places that could be prepared for a weightlifting event and the competitors made use of these convivial locations by challenging each other to lift barrels of beer and wine. However, while such participants often displayed rough or unrefined techniques, they also demonstrated great sporting talent.

In this historical context, newspapers played a crucial role, not only in disseminating news about performances, but also as guarantors of competitive reliability and standards. In Vienna, the wealthy Victor Silberer was the owner and editor of the Allgemeine Sport Zeitung newspaper, founded in 1880. Thanks to his extensive network, in particular with the United States, namely at the The Spirit of the Times sporting newspaper and, later, The National Police Gazette, both from New York, he spread word about the excellent performances of Viennese weightlifters, promoting international recognition. Conversely, the readers of Allgemeine Sport Zeitung knew about the performances of American athletes.

From 1884, the performances of Georg Jagendorfer, Franz Stöhr, and Wilhelm Türk became internationally recognised in the press. This flow of information, connected to unofficial world records in weightlifting between the two sides of the Atlantic, soon extended to other authoritative newspapers such as Sporting Life in London, Illustrierte Athletik Sportzeitung of Munich and several Russian, Italian and French newspapers (including L’Auto and La culture physique).]

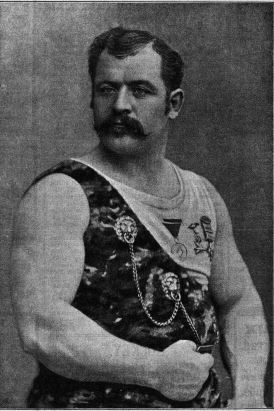

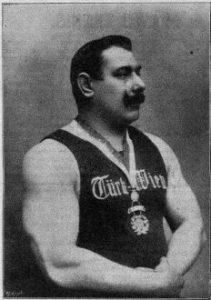

Georg Jagendorfer

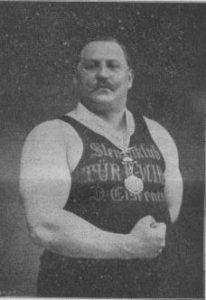

From 1890, thanks to Stöhr and above all to Wilhelm Türk, Vienna acquired a prominent position in weightlifting. At that time, there were many weightlifting disciplines, however, performances in the two-handed jerk and press were considered to demonstrate the supremacy of the strongest athlete. Silberer’s newspaper and other Viennese journals exalted the strongmen of Vienna, and from 1897, after Türk had won a distance duel with the German Hans Beck, the concept of Vienna as the city of strongest men became a point of pride. Türk was hailed as the world’s strongest man thanks to his victory in the Vienna World Championships on 31 July 1898. Although it was an unofficial event, the quality of the championship was indicated by the presence of the excellent French athletes Bonnes and Maspoli, as well as the Russians Hackenschmidt and Meyer. The view that Türk was the world’s strongest man was confirmed by authoritative spectator and weightlifter Luigi Monticelli Obizzi to readers of Italy’s Corriere dello Sport/La Bicicletta in his short, explanatory, biographies of the various lifters in attendance.

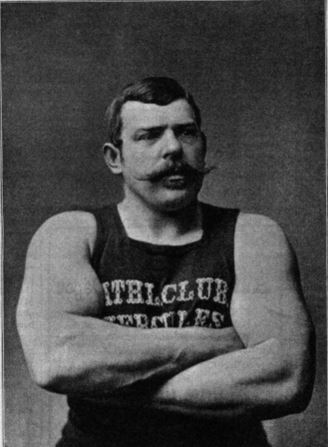

Wilhelm Türk

A controversial feature of Viennese superiority laid in executing the two-armed jerk using what the British described as the ‘Continental style’ – this style utilised three distinct phases to lift the bar, rather than two. Thanks to this technique, Türk set a record for the two-handed jerk of 160.5 kilos in 1901 – Bonnes, the leading French athlete, stopped at 141 kilos. In comparing the different techniques used by the lifters, Monticelli Obizzi acknowledged the style used by the Austrians was an advantage, but, irrespective of this, declared Türk the superior athlete. The value of Viennese performances was seldom recognised within French-inspired weightlifting.

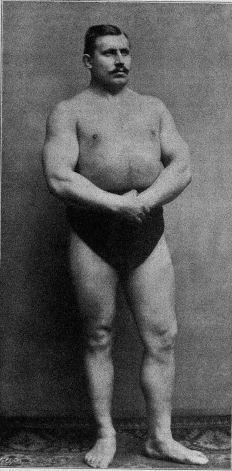

Josef Steinbach

Before the Great War, the World record passed from Türk to Witzelsberger, then to Steinbach and Swoboda who in 1911 set it at 185.6 kilos. Amongst French lifters, the corresponding record was just 151 kilos. The uninterrupted holding of the two-handed jerk record in this period was the first founding element of the myth of Vienna as the city of the strongest men. This myth would be constantly regenerated and, as generations passed, the sceptre of supremacy remained in the Austrian capital. Records for the lighter weightlifting body classes began at the start of the twentieth century and Austrians were among the best in these divisions too.

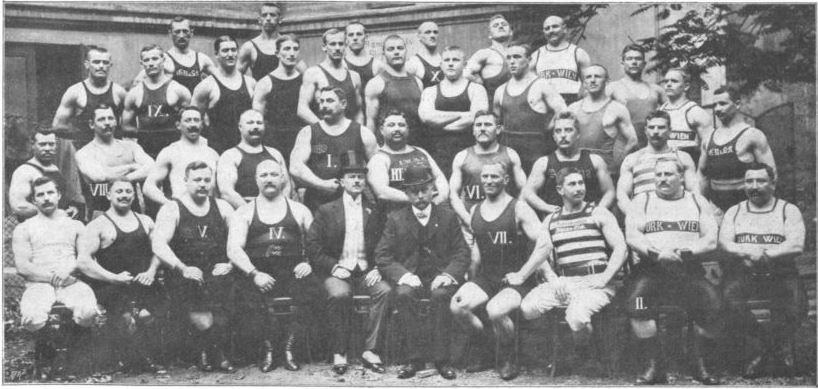

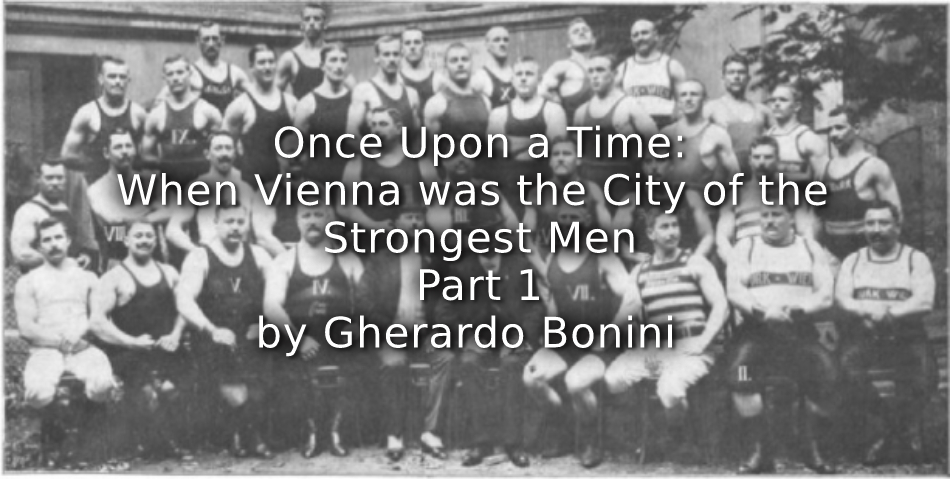

Participants in the World Championships of Vienna 1909

With I Grafl, II Swoboda, III Tandler

In 1914, there were about 120 weightlifting clubs in Austria, very few outside Vienna, fewer than in Germany and almost the same as in France. In wrestling, the cities of Graz, Innsbruck, and Salzburg vied with Vienna for national supremacy and challenged the international elite. While the declaration of Viennese supremacy was little recognised in foreign newspapers, a number of records and titles, sometimes unofficial, supported the assertion – these included victories outside Vienna. In 1906, Steinbach won the title at the Intercalated Games in Athens; in 1910, Josef Grafl won the heavyweight World Championships in Düsseldorf and those, recognized by an short-lived international federation, in Breslau in 1913.

Josef Grafl

Source: Atelier Krotsch, photographic company

After World War I, Austrian sport needed to be rebuilt and it relied on Vienna, the city of strong men, to produce talent for the new generation of weightlifters. Like Germany, Austria was banned from participating in the Antwerp Olympics of 1920 and in September of that year a ‘real Olympics for heavier athletics’, was organised in which the lifters produced better results than those in the Antwerp games. However, Vienna suffered a crushing defeat because four out of five titles were won by Germany. Among heavyweights, Swoboda withdrew, giving up his second place, after being unable to better the German athlete Mörke.

Karl Swoboda

Austrian weightlifting would again be represented in the Olympic arena in Paris in 1924, but before this happened a new problem emerged that threatened their pre-war dominance. In 1920, the French had re-founded the International Weightlifting Federation (Fédération internationale d’haltérophilie) and banned the ‘Continental style’ beloved in Viennese weightlifting circles. If Vienna’s reputation as a city of strong men was to be revived on the international stage, Viennese associations, athletes and coaches would have to fundamentally change their technique, training and performances.

Article © Gherardo Bonini

Read Part 2 HERE

![“And then we were boycotted” <br> New discoveries about the birth of women’s football in Italy [1933] <br> Part 2](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/And-then-we-were-boycotted-New-discoveries-about-the-birth-of-womens-football-in-Italy-1933-Part-2-by-Marco-Giani-440x264.jpg)

I have a feeling weightlifting did not feature in the 1908 or 1912 games so the Viennese couldn’t get titles. Grafl turned professional and did some pro. wrestling before trying his luck in Hollywood silent films.